There's something weird going on with the US economy.

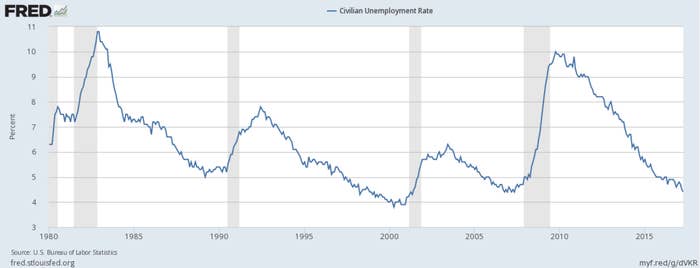

It's steadily adding new jobs, at a pace of about 185,000 every month. Unemployment keeps falling: at 4.4%, it's at its lowest since May, 2007. But people's wages aren't growing at the rate you'd expect them to when unemployment is this low and hiring is so healthy.

So what's happening? One explanation is there's a larger pool of people who are starting to look for work — people who weren't previously considered unemployed. If that's the case, companies don't need to boost wages to compete for workers, because there's more people out there who had given up even trying to find a job until recently — and now they're coming back into the workforce.

That scenario depends on what percentage of the adult population are "participating" in the labor market, either by working or looking for a job. The labor force participation rate has been in decline since 2000, thanks in large part to the aging US population. But it held steady in the last two years, and the unemployment rate fell to a historic low, suggesting plenty of people who were counted as being out of the labor force have been rejoining it as the economy improves, even as older people drop out entirely.

The US unemployment rate, from 1980 to today:

Why those people left the workforce, and why some are returning, has become a popular guessing game among economists trying to figure out one of great mysteries of today's economy.

Federal Reserve researchers argued in 2014 that "nearly half of the

decline" in labor force participation was due to the the growing number of baby boomers hitting retirement age. But what about the other half?

For younger and adult men, whose participation rate declined severely following the recession, the Fed researchers cited "longer-run changes in the labor market," including higher college enrollment rates and employers preferring more educated workers. Each contributes to people dropping out of the workforce — either to study for the skills needed to get a job, or because nobody will hire them.

Other research even suggested that some young men might find it easier to exit the workforce because of the availability of better, more immersive video games to whittle away the days. The growing number of older men reporting chronic pain and disability — and the ongoing opioid addiction crisis — has has also taken its toll.

But while men in their twenties still aren't as likely to be working or looking for work as they were in the past, the larger trend is that working-age people are re-entering the job market. Among people aged 25 to 54, 78.6% are now employed, up from 77.7% two years ago, and their labor force participation rate has inched upwards.

Importantly, the number of people who say they are not in the labor force because of disability, poor health, or family responsibilities has declined compared to the population as a whole, according to data compiled by Adam Ozimek, an economist and analyst at Moody's.

"After trending upward steadily since the recession, the number of adults age 25 to 54 who are out of the labor force because they say they don't even want a job has declined by half a million over the last year," Ozimek wrote recently.

The labor market is improving "in categories where people thought we weren’t going to to see improvement," Ozimek told BuzzFeed News. "The improvement is pretty widespread."

But while the size of the workforce and how many people are employed are one part of the equation, the wages they are paid is the other. And the fact that wage growth is steady, but not accelerating, suggests there are still plenty of people out there rejoining the job market — and as they re-enter, they ease the pressure on companies to raise pay.

"We’re adding around two million jobs a year year — about 170,000 a month — and we only need 60,000 to 70,000 to keep up with population growth," Ozimek said. The steady supply of new jobs is enough to get the attention of those who exited the workforce, and "as wages go up they start looking for work again. Somebody is hiring 2 million net new jobs a year."