More than six years after the financial crisis, top officials at the Federal Reserve have a stern message for the financial industry: fix your culture or risk further punishment, including getting broken up.

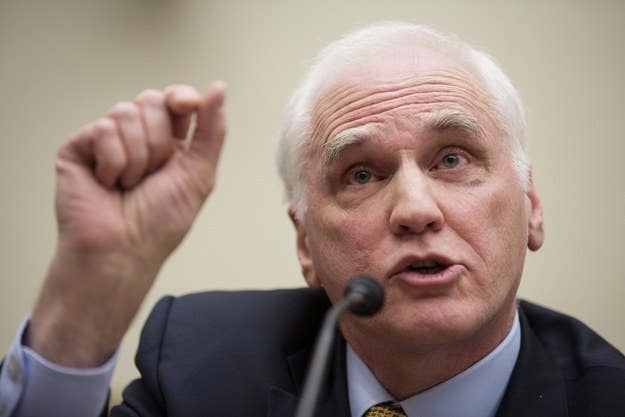

At a conference Monday hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which supervises many of the largest banks, its president William Dudley told the assembled bankers that cultural problems at large banks have persisted past the financial crisis and that he rejects "the narrative that the current state of affairs is simply the result of the actions of isolated rogue traders or a few bad actors within these firms." He pointed to JPMorgan's $6 billion derivative loss, criminal convictions of European banks for violating sanctions and helping Americas evade taxes, and the widespread manipulation of the reference interest rate known as LIBOR by bank traders.

Dudley, who gave the usual disclaimer that he was speaking on his own behalf and not on behalf of the entire Fed, told the bank executives that if "[you] do not do your part in pushing forcefully for change across the industry," the "inevitable conclusion" will be "your firms are too big and complex to manage effectively."

Dudley, a former economist at Goldman Sachs, has been criticizing large banks' culture and compensation policies in public forums for about a year and has done so twice in the last month. Dudley was speaking at the New York Fed's "Workshop on Reforming Culture and Behavior in the Financial Services Industry," with senior bank officials like Morgan Stanley's chairman and chief executive officer James Gorman, JPMorgan Chase's chief operating officer Matt Zames, Goldman Sachs securities co-head Pablo Salame, Citigroup compliance chief Brian Leach and UBS chairman Axel Weber listed as attending.

The Federal Reserve boardmember in charge of supervision, Daniel Tarullo, also spoke at the workshop, giving a similiar message to Dudley. "If banks do not take more effective steps to control the behavior of those who work for them," Tarullo said, "There will be both increased pressure and propensity on the part of regulators and law enforcers to impose more requirements, constraints, and punishments."

Dudley told the assembled bankers "the problems originate from the culture of the firms, and this culture is largely shaped by the firms' leadership. This means that the solution needs to originate from within the firms, from their leaders."

Dudley suggested that the size and structure of large banks have lead to cultural shortfalls at banks where bank employees take large bets that endanger the firm or treat the bank's clients in a way that extracts as much money from them as possible in the short term. "Interactions became more depersonalized, making it easier to rationalize away bad behavior," Dudley said, "and more difficult to identify who would be harmed by any unethical actions."

As he has before, Dudley also said that existing payment practices could be reformed to adjust banker behavior. Dudley said that if senior bankers — and employees in a position to make big mistakes — were paid with the bank's debt over a long time period as opposed to its stock, they could take a longer view of how their actions affect their bank.

Think of it like the deposit on an apartment encouraging the tenants to keep the place in good condition. Or as Dudley put is, if a "sizable portion" of a large bank fine, for instance, was paid out of that deferred debt, it would "increase the financial incentive of those individuals who are best placed to identify bad activities at an early stage, or prevent them from occurring in the first place."

Dudley also said that banks could implement a "central registry that tracks the hiring and firing of traders and other financial professionals across the industry" so that employees who are fired for committing an ethical or legal lapse do not just get bounced to another financial institution. Something like this already exists for brokers and is run by FINRA, the brokerage industry's self-regulator.

At the same time, the New York Fed, which is the most powerful of the 12 Federal Reserve banks and, under the leadership of Tim Geithner, was one of the most important institutions in shoring up the financial system during the crisis, has come under fire for its own approach to supervising banks. .

A recent ProPublica story depicted the New York Fed in 2012 as unwilling to directly confront large banks like Goldman Sachs even when its own staff had determined behavior was inappropriate. It also reported on an internal study conducted by an outside expert which concluded that the New York Fed had "a culture that is too risk-averse to respond quickly and flexibly to new challenges" and that its own staff thought it was too deferential to the banks it supervised.

Dudley has defended the New York Fed's supervision and its staff but has said that "improving supervision has been and remains an ongoing priority for me."

"Good culture cannot simply be mandated by regulation or imposed by supervision," Dudley said at the workshop Tuesday.