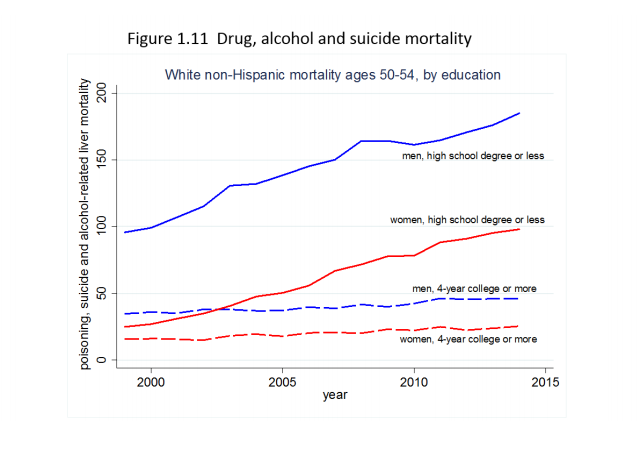

Middle-aged white Americans without college degrees are dying at higher and higher rates, with drugs, alcohol, and suicide driving a dramatic increase in mortality.

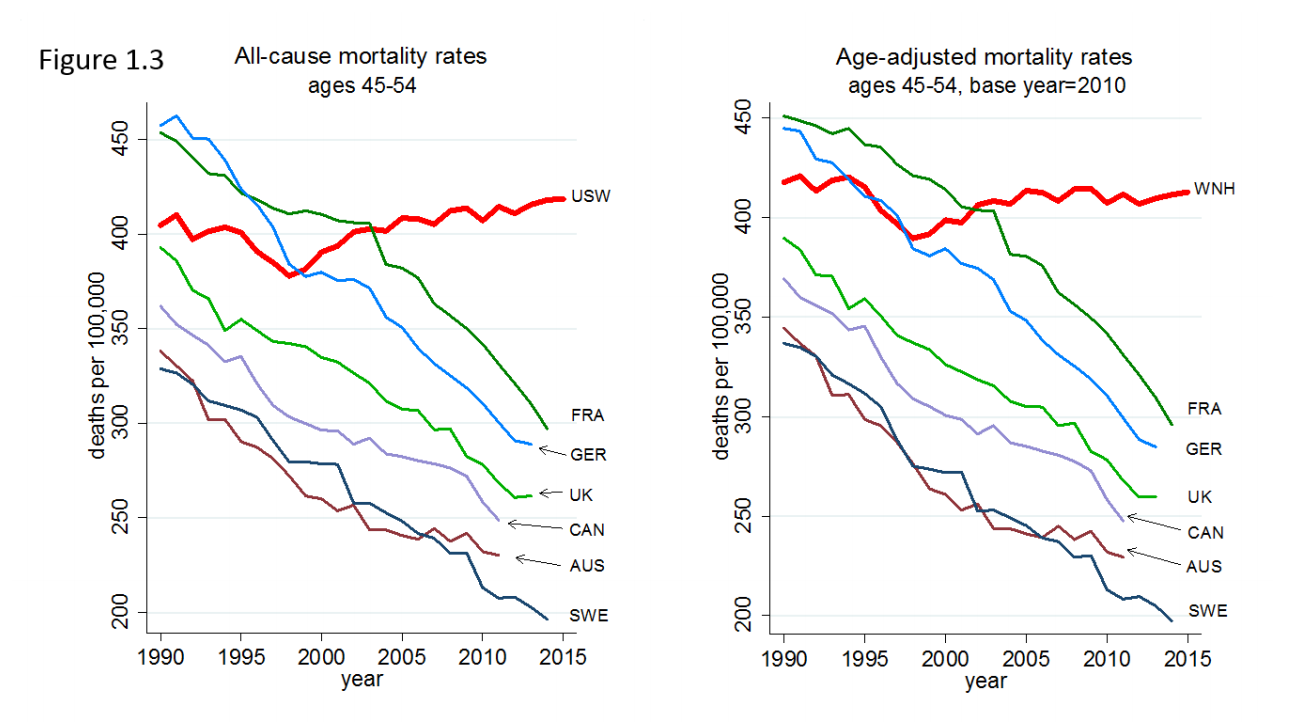

The increase is happening even as mortality decreases for similar age groups across the developed world — and for black and Latino Americans, and whites with college degrees.

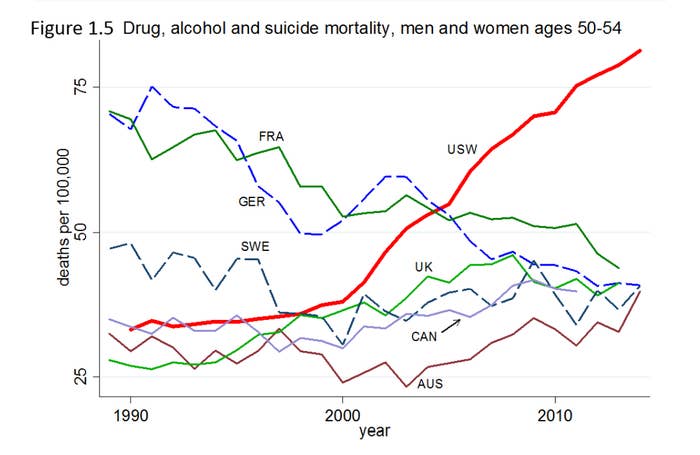

The data, outlined in a new paper by economists Anne Case and Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton, shows death patterns for American whites sharply diverging from peers in Western Europe — particularly in what they dub "deaths of despair," involving drugs and suicide.

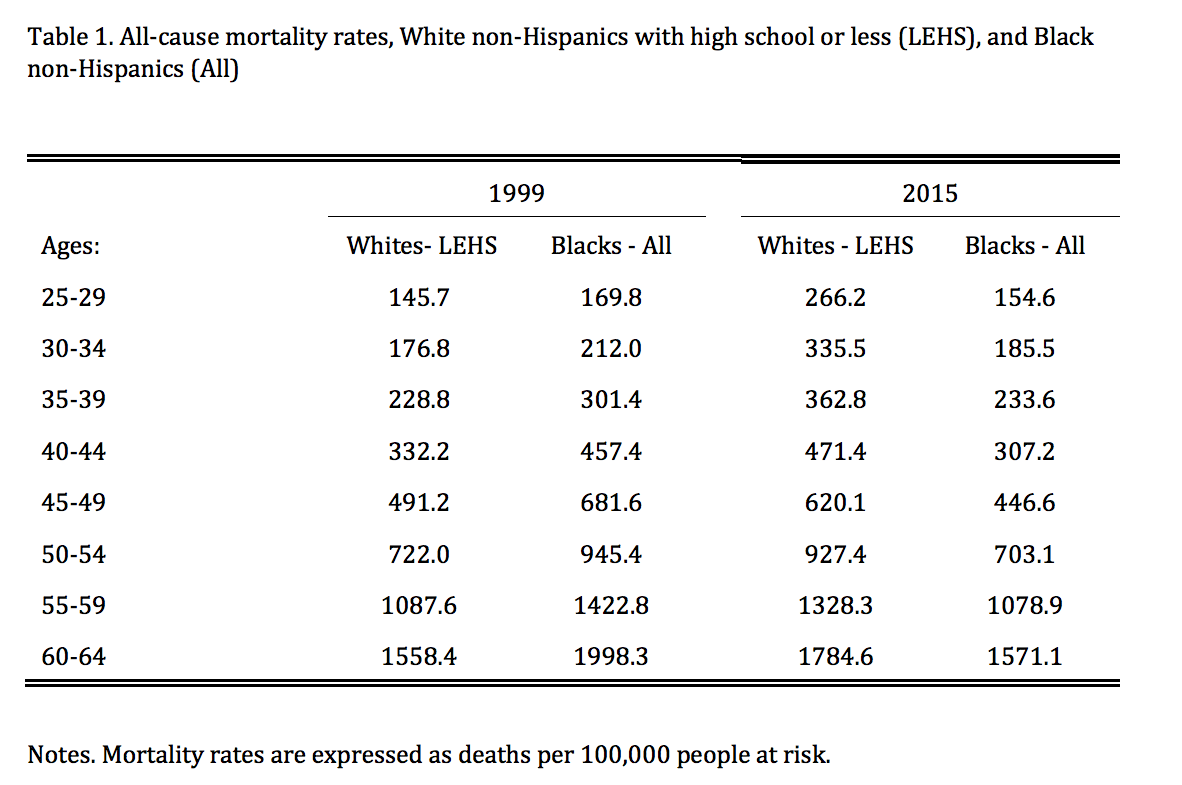

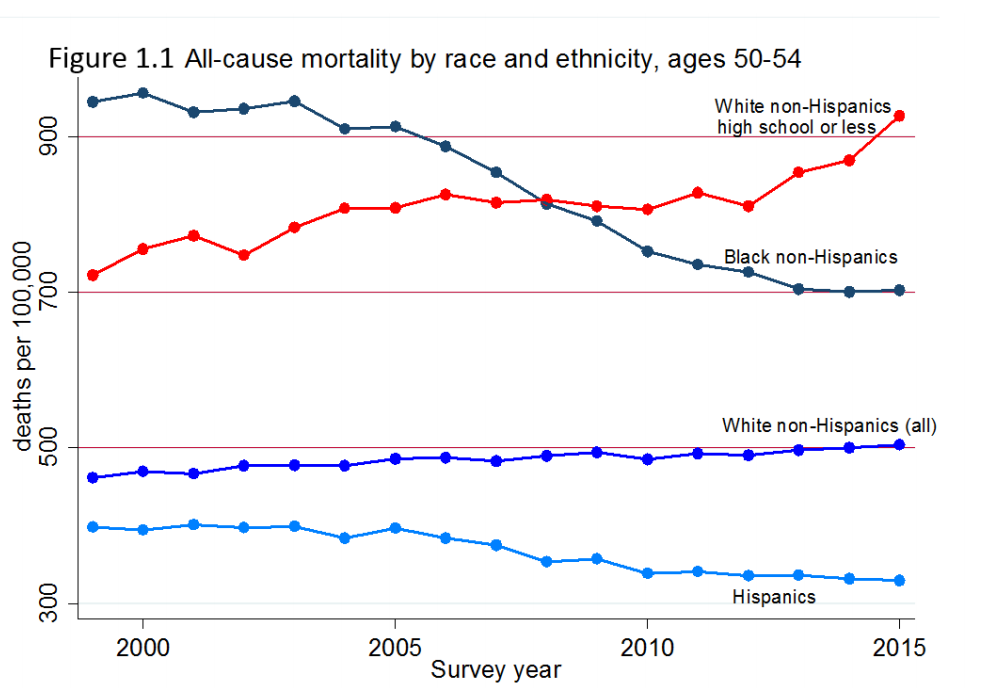

"In 1999, the mortality rate of white non-Hispanics aged 50-54 with only a high school degree was 30 percent lower than the mortality rate of blacks in the same age group," Case and Deaton wrote. "In 2015, it was 30 percent higher."

The rising mortality affects a wide swath of the country. There are 90 million white Americans aged 25 or older who have no bachelor’s degree — more than all black, Asian, and Hispanic adults over 25 combined.

For college-educated white America, the US is a typical Western industrialized country, with falling mortality rates across demographics. The same goes for minority groups: Hispanics have experienced a decline in mortality comparable to rich European countries (although the overall level is still higher), while African-Americans have experienced large, sustained drops.

The trend goes against a broad global improvement in public health through most of the 20th century. In the US, mortality fell from the late 1930s through to the late 1990s, pausing only in the early 1960s after smoking became a national pastime. If the mortality rate simply stopped falling and flatlined, it'd be a crisis. The fact that it's increasing is disastrous.

The numbers behind such trend lines are stunning: If mortality for whites aged 45–54 had fallen between 1999 and 2013 at the same rate as it had between 1979 and 1998, half a million fewer people would have died, Case and Deaton have previously noted — a number comparable to all the lives lost in the US AIDS epidemic.

In many European countries, "mortality rates are falling for all education groups, and are falling most rapidly among the least educated," Case and Deaton wrote. "The fact that the US has pulled away from comparison countries throughout middle age is cause for concern."

The massive increases in mortality among the non–college-educated white population has led to the overall white life expectancy at birth to fall in 2014 and for the overall life expectancy to fall in 2015.

The usual suspects did not cause this turnaround. Deaths from heart disease and cancer — the two largest killers of the middle-aged— have fallen. Instead, increases in drug overdoses, suicide, and liver diseases caused by alcohol have been able to more than offset these vast improvements in public health.

Money also doesn't explain the divergences. The incomes of black and white Americans have moved in a similar pattern, and non–college-educated blacks suffered bigger income falls since 1999 — and yet their mortality rates declined.

For whites in middle age, however, "there is a strong correlation between median real household income per person and mortality from 1980 and 2015," Case and Deaton write. What's really happening, they suggest, is not so much short-run changes in income, but that "long-run stagnation in wages and in incomes has bred a sense of hopelessness."

Case and Deaton's work follows their blockbuster research in 2015 that showed that there had been 96,000 "excess deaths" between 1998 and 2013 thanks to the increase in mortality rates among whites between 45 and 54.

Other economists have shown that middle-aged white men are leaving the workforce at higher rates due to increases in pain and disability, and that employment, earnings, and marriage rates for men had fallen in areas where jobs disappeared to increased competition from foreign manufacturers.

Many media accounts of the declining prospects of the white working class discuss the rise of opioid addiction. Case and Deaton are more cautious, saying "we do not see the supply of opioids as the fundamental factor," but that "prescription of opioids for chronic pain added fuel to the flames, making the epidemic much worse than it otherwise would have been."

African-Americans are also considerably less likely to be prescribed opioid painkillers, which is the first step for many future addicts to full-blown dependency.

The underlying story, Case and Deaton suggest, is economic.

Since the early 1970s, people without a college degree have had fewer good career opportunities, stagnant wages, shrinking unions, declines in church membership, and fewer marriages. "These changes left people with less structure when they came to choose their careers, their religion, and the nature of their family lives," Case and Deaton wrote. "When such choices succeed, they are liberating; when they fail, the individual can only hold him or herself responsible."

"Cumulative distress, and the failure of life to turn out as expected is consistent with people compensating through other risky behaviors such as abuse of alcohol, overeating, or drug use," they wrote.

"Ultimately, we see our story as about the collapse of the white, high school educated, working class after its heyday in the early 1970s, and the pathologies that accompany that decline."

Outside Your Bubble is a BuzzFeed News effort to bring you a diversity of thought and opinion from around the internet. If you don’t see your viewpoint represented, contact the curator at bubble@buzzfeed.com. Click here for more on Outside Your Bubble.