The following is a work of fiction that has been excerpted with permission from Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous, published by HarperCollins India.

Miss Iyer’s short film ‘How Feminist Men Have Sex’ opens with the girl walking down a corridor of a hotel. The camera trails her as it often does in her films. She is in a white shirt, and red pants, which surely have a more specific description, and comfortable blue shoes. She stops at a shut door and turns towards the camera.

“We’re about to meet a top political economist. He even knows what it means.”

“We’re about to meet a top political economist. He even knows what it means. He is from Delhi. As you know, he is also a columnist, television commentator, and a man with a moral compass,” she says with a deadpan face. This is not the deadpan of a comedian whose seriousness is a part of the act and a foreboding of an approaching joke. The deadpan of Miss Iyer is not frivolous.

“Last week he published a thoughtful piece titled, ‘Breakfast to bed: Why Indian Men Should Be Feminists’,” she goes on about the man with the moral compass, standing at the door of his hotel room. “The essay has been read online by over a million people, including men.”

Moments after she rings the doorbell, an elegant middle-aged man opens the door.

Gautam Rajan is of a type: high caste, socialist, bearded, alumnus of an American college, champion of equality, beneficiary of inequality, allergic to capitalism, large dams and nationalism. He has called Damodarbhai a “fascist”. He probably meant it in a bad way.

Rajan is highly articulate, verbally articulate, a quality that people do not see as charlatan. But the fact is life is complex and mysterious, histories unreliable, all philosophies ambiguous, almost nothing is fully known or understood; can an honest mind ever be articulate?

Rajan is unaware that the recording has begun. Also, he is certainly not familiar with the nature of Miss Iyer’s films or what the young woman is about. She walks into the hotel room and introduces the unseen cameraperson, who is a woman.

“Akhila,” Rajan says with a gracious hand on her slender shoulder, “How nice to meet you, and how interesting to be you. And how lucky for Indian journalism that bright girls like you from science are flocking to it.”

Rajan has called Damodarbhai a “fascist”. He probably meant it in a bad way.

Miss Iyer gives him a shy smile, lampooning feminine submission. “I know I must crack a self-deprecatory joke right now, sir, but I can’t think of one,” she says. It is an omen but Rajan misses it.

She had probably shot the film before she began uploading her works. She probably shot most of her short films before she released any of them so that her subjects would not be forewarned.

Miss Iyer and Rajan are now seated across a coffee table.

“Start?” he says with a sideways glance at the camera, which makes him look foolish already.

“Yes Mr Rajan.”

“Please call me Gatz.”

“Call you what?”

“Gatz.”

His phone rings. He apologises, considers the device and kills the call.

“I see you’ve a Blackberry,” she says.

“Yes. I like Blackberry. I’m not an Apple fan.”

“I used to have a Blackberry, sir.”

“Everyone did, once.”

“I had a problem with its keypad. The buttons were so small. Fiddling with it was exactly like searching for my G-spot.”

“It’s unusual for me to speak as a feminist. But that’s good, that’s very good.”

Rajan issues a cautious smile, but he is yet to suspect the nature of the interview. His phone rings again, and once again he cuts the call.

“I’ve been on phone all day talking to journalists,” he says, “It’s unusual for me to speak as a feminist. But that’s good, that’s very good.”

“The journalists are still calling you about your article?”

“No, no. You’ve not heard the news?”

“I’m clueless, Mr Rajan.”

He says an incident occurred in the morning. A professor of creative writing has caused a major stir. “This jerk said during a panel discussion that he has to just read a short-story submission without knowing who the author is and he would be able to tell if the writer is a woman. Don’t these guys ever stop? How many imbeciles are there in the academic and literary world?”

“Did he say, Mr Rajan, what makes him identify a female writer so easily?”

Rajan is surprised by the question. “No. These guys are never that specific.”

“Maybe what he meant was that when a short story is deep and brilliant and without gimmicks the author is usually a woman.”

“That’s not what he meant, I am sure.”

“The fact, Mr Rajan, that he can identify the author of a work as a woman also means, by default, he can tell if the author is a man. Why aren’t men pissed?”

Rajan throws a quick look at the camera. “My dear girl,” he says, “His statement has a specific meaning. There is a context to it. And there is history. There is a tacit insult in this sort of view. And every woman knows what he means.”

“Every woman?”

“Every woman.”

“Three billion women must be a single collective organism.”

“Mr Rajan, what do you mean when you say you are feminist?”

His face grows serious, he throws another nervous look at the camera. A gentle smile of incomprehension appears on his face. She stares at him in silence as though expecting him to say more. When he is about to speak and end the bizarre silence she interrupts him with a question. “Mr Rajan, what do you mean when you say you are feminist?”

He takes a moment. And when he speaks he stresses every syllable. “Equality”. He then repeats it more emphatically, “Equality. Unambiguous nonnegotiable equality.”

“Equal to who? Equal to men? Equal to you? But there must be more to a woman’s life.”

Rajan tries to achieve a graceful nod.

“Equality and respect,” he says, “Unambiguous nonnegotiable respect. When men respect women they are feminists.”

“Can they watch pole-dancing?”

“Excuse me?”

“Is a male feminist allowed to watch pole-dancing?”

Rajan rubs his nose. “Informed, intelligent men do not objectify women.”

“Have you, sir, ever objectified a woman?”

“This is the dumbest question in the world.”

“It’s the dumbest question in the world because you obviously do objectify women?”

“I never. Never. Never.”

“How do you fuck?”

Rajan begins a long glare at the camera. He is not sure yet whether this is a prank. If the interview is genuine and he terminates it he would look petty, like sensitive Hindu patriots whom he condemns. He is a liberal, and liberals must stay the course of an unpleasant interview. He shifts his stare to Miss Iyer. His paunch begins to rise and fall with every deep breath. “I don’t do that…”

“You don’t bonk?”

“First of all it’s called ‘making love’”

“Making love.”

“Yes, making love.”

“Do you, sir, make love?”

“I am the kind of man who gets excited by a woman’s intellect, spirit and humour.”

“As in your lady is sitting on the bed reading and you look at her and think, ‘Oh my adorable lady devouring Roger Penrose’. And you are consumed by an intense respect for her, which makes you very very hard.”

“I am the kind of man who gets excited by a woman’s intellect, spirit and humour.”

Miss Iyer shuts her eyes and begins to pant. “In the yellow light of the Japanese lampshade that you bought because she was busy, as you see her middle-aged face and sagging neck you ogle at her deep inner intelligence and wit, and your respect is escalating, and now you’re so hard it’s hurting you.”

Rajan says in a low shivering voice, “What’s going on?”

Miss Iyer rises but her eyes are still shut and she is panting harder. She holds an imaginary body and begins gentle pelvic movements that suggest, in Vaid’s biased perception, doggy sex. “Darling…darling… I so respect you …Tell me something cleverly funny; tell me once again, darling, why did you read Hegelian Dialectics upside down.’ And your darling moans, ‘Because, baby, as a Marxist that’s the only way I can read Hegel right’. You’re in a tizzy now, sir, she is so clever. You’re so so hard.”

Rajan turns to the camera, which moves back a few feet. “Leave,” he says.

But Miss Iyer goes on, continuing her pelvic action: “You say, ‘Darling, let’s move on to general knowledge. What’s is the most common name in Vietnam?’ And she says, with a perfect Vietnamese accent, while somehow managing to moan, ‘Nguyen, Nguyen’. You, sir, rasp, ‘I respect you so… darling. Next quiz question, honey. What’s the difference between recursion and iteration?’”

Rajan rises. A bird-like sound leaves his lungs.

“Sir,” Miss Iyer says, “I don’t follow your dialect anymore.”

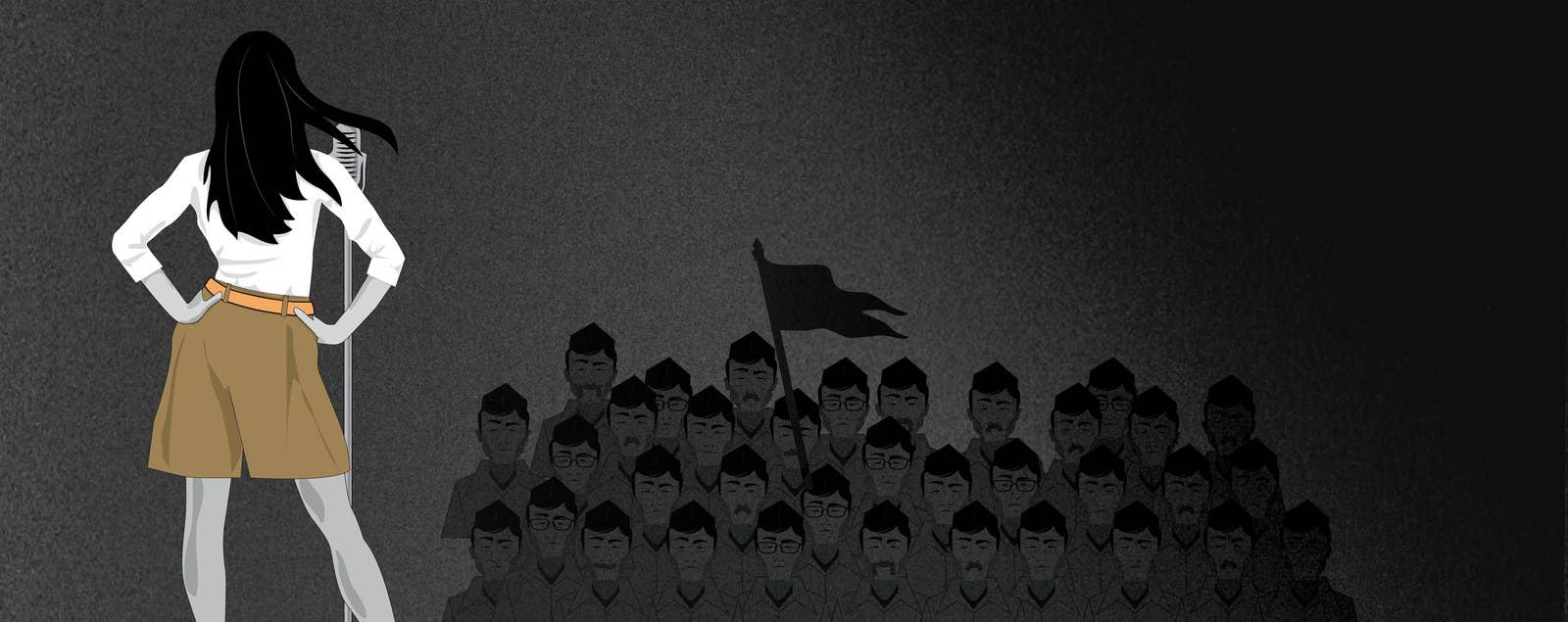

A prank need not have an objective, but Miss Iyer does. The messages in ‘How Feminist Men Have Sex’ are simple – the impossibility of sex as a reverential act, and that modern men who claim to be feminists without the experience of living in a female body are frauds; and that an erection is the same hydraulic event in political economists as it is in jackasses.

A question for the author

Keeping the characters of your novel aside, what is your view of male feminists?

Everything that women expect "male feminists" to be, men can achieve through intelligence and decency alone; strange labels are not required. In fact, the existence of such labels as 'male feminists' only allows some men to pass off as better people. Also, we need to move beyond ideas like 'equality'. Equality is a trap, its underlying message is that you can only be equal to those who dominate you, not better. What we need to work towards is a world that is not dominated by the male way of doing things.