More than a decade ago, Saw, directed by James Wan and written by and starring Leigh Whannell, became one of the most profitable horror movies of all time. Now, after writing two more Saw movies and two films of a second franchise, Insidious, Whannell is making his directorial debut with Insidious: Chapter 3.

"Filmmaking seems to me to be a lot like skydiving. You can watch a bunch of videos about skydiving. You can learn the theory of it. But you don't really know what it's like until you jump out of that plane," Whannell told BuzzFeed News at L.A.'s iconic Chateau Marmont, where he wrote most of the third Insidious film. "I don't know that I was ready at all."

It's a big change for Whannell: Insidious: Chapter 3 not only marks his first time as a director, but also his separation from Wan, whom he met in film school in their native Australia. They embarked on a joint career that yielded Saw (Wan directed Saw and co-wrote the story of Saw and Saw III with Whannell, who wrote and starred in the first three) and Insidious (written by Whannell, with a story assist from Wan, who directed the first two). Wan has moved on to big-budget studio films, like Furious 7 and the upcoming Aquaman. And although he was a producer on Insidious 3, Wan was "pretty hands-off," which had its advantages and disadvantages for first-time director Whannell.

"My identity was so wrapped up in being one-half of the Wan-Whannell duo, and I realized I didn't know who I was without James," Whannell said. "He was doing Furious 7 at the time, which was kind of a hurricane of a production, with all this tumultuous activity that happened and the tragedy with Paul Walker, which stopped production. So he was right in the eye of that storm, and I think he really helped by what he didn't do. He didn't lean over my shoulder and tell me to do this, that. He didn't give me notes or tell me to change things."

At the same time, Whannell acknowledged that working without Wan at his side was at times a difficult change. "Things like that always turn out to be the events in your life that kind of shove you forward," he said. "It's like when you first move out of home and you have your own apartment, and you're thinking, Oh my god, this is so difficult. And then you learn the ropes and you sort of get shoved up the evolutionary ladder a little bit.

"It's been an ever-evolving journey. This is my first time, and I'm gonna have to learn by making mistakes."

Whannell's interest in horror began at a young age: While his friends were extolling the virtues of Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark, he was haunted by Jaws. And that particular genre had its practical advantages for Whannell when he and Wan were looking to make their first feature after film school. Once the duo realized that no one was particularly interested in blindly funding their work, they sought out to create something on their own.

"We started trying to calculate how much money you could make a film for at the absolute base level," Whannell said. "Horror is probably the only genre where a bigger budget doesn't really help. 'Cause what are you gonna do with that extra money? Are you gonna create a special effects sequence where a city gets knocked down, like something out of Man of Steel? … It's a very friendly genre to first-time filmmakers."

But even working within horror, Whannell and Wan had to look for ways to cut costs. Their first movie had to be very contained — the film equivalent of television's "bottle episodes" that lower the budget by taking place all in one room. It was in those early brainstorming sessions that they stumbled on the idea for Saw.

While the sequels to the 2004 film upped the ante on gore and world expansion, Saw itself is a small movie — the story of two men, Lawrence Gordon (Cary Elwes) and Adam Stanheight (Whannell), who find themselves chained up in a basement with instructions that one must kill the other in order to escape.

"Essentially, Saw is the result of us pushing ourselves to come up with this movie," Whannell said. "I always loved the story. There was something about that story for Saw, as I was writing it, that gave me confidence — not so much confidence that it would be a hit movie, but confidence that people would like it."

And they did. Saw turned out to be a massive success, grossing more than $100 million worldwide, birthing a franchise, and becoming a part of the pop culture lexicon. Given the low expectations Whannell and Wan had, Saw's staggering popularity was a thrilling surprise.

"I knew that people would respond to it — I just didn't think it would happen on that level," Whannell admitted. "I'm still, to this day, pretty chuffed, pretty happy, that we made a film that impacted popular culture, to the point where journalists had to think up a term to describe the movie."

The term they came up with was "torture porn," a controversial designation that Whannell has softened on over the years. While he was initially resistant to that characterization, Whannell acknowledges that the franchise came to embrace the title over the years.

"I'm the first to admit that the sequels to Saw got progressively more gory. It's almost like the film retroactively earned that label that it had been given," he said. "You know, like somebody pointing at you, saying, 'Your shirt's dirty,' and you're like, 'You want to see dirty? I'll give you dirty.' And you go and roll in the mud."

Because of the increased focus on bloodshed, Whannell found writing the Saw sequels to be a challenge. He wanted to focus on the story and the characters — and the first three Saw films do offer developed arcs and intricate backstories — but he was under constant pressure to ramp up the brutality.

"The producers would be in my ear saying, 'More traps, more blood,'" Whannell said. "Because they thought that's what the audience wanted, and it sounds like they were right. I tried as much as I could to at least have a strong story, and maybe that's the reason I couldn't write any more Saw movies."

He departed the series as a writer after Saw III, but remained an executive producer (along with Wan) through the seventh installment. "I don't know that I could have come up with any more great stories," he said. "I basically would have been coming up with five or six gory death scenes and then trying to link them somehow. I guess I didn't feel like I had any more to offer."

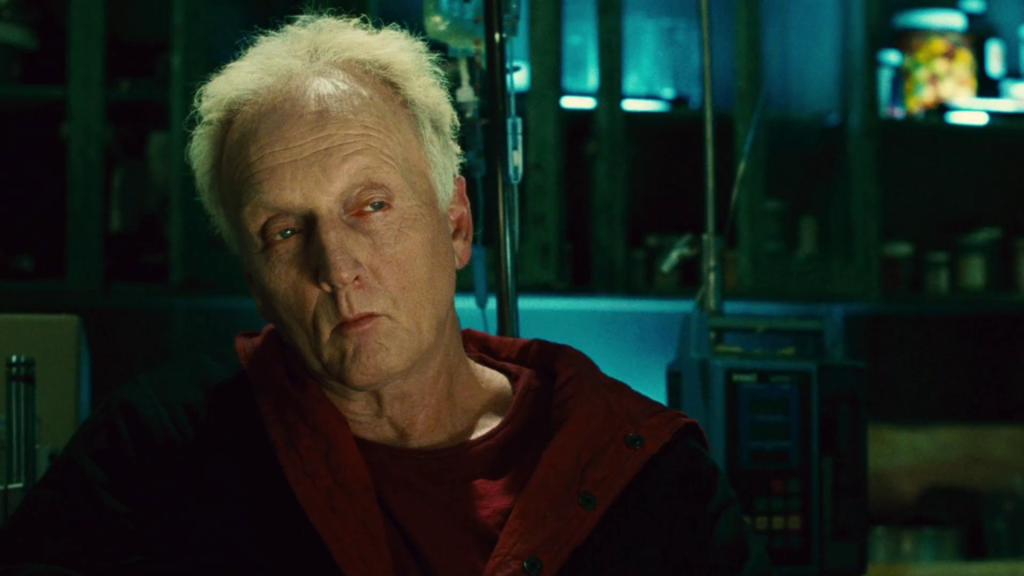

Before he stopped writing Saw sequels, however, Whannell was able to inject Jigsaw (Tobin Bell), the serial killer at the center of the series, with one of his most defining characteristics: terminal brain cancer. The idea came from Whannell's own health problems during the production of the first Saw movie.

"I was having basically anxiety attacks but they were manifesting themselves with headaches and heart palpitations and all this scary stuff, especially since I was in my mid-twenties when you just take health for granted," Whannell recalled. "And it really scared the hell out of me, and I ended up incorporating that into the [Saw II] script."

Giving Jigsaw — or his alter ego, John Kramer — health problems was part of Whannell's attempt to develop his characters past types, and to add substance to a film that might otherwise be all about its violent set pieces. Illness and recovery have since become something of a recurring trope in Whannell's work, even outside of the Saw films.

"It's just something that's buried in my subconscious that keeps kind of punching its way through to the surface of these scripts," Whannell said. "It's not something that I realized at the time, but now when I look back, almost every film I've written has involved some sort of injury or illness, so I think it's one of those things that keeps recurring thematically even without me pushing it. I'm terrified."

Insidious: Chapter 3, which incorporates a nasty car accident and a demon with respiratory trouble, is no exception.

The Insidious franchise began in 2011 and was a much-needed second hit for Whannell and Wan, who'd just come off a couple of disappointments in 2007: Dead Silence, which Whannell wrote and Wan directed, and Death Sentence, directed by Wan, with Whannell taking on an acting role.

"We had come out with Saw, and we had done our little victory lap of Hollywood where everybody wants to high-five you because you've done well, and then we had a couple of years in the wilderness," Whannell said.

Then came Insidious, for which the duo teamed up with Jason Blum's Blumhouse Productions, notable for producing low-budget horror that often goes on to find mainstream success. Insidious, which was made for a paltry $1.5 million and earned nearly $100 million, was a perfect fit.

"The model [Blum] was offering us was very similar to what we did with Saw," Whannell said. "With Saw, we had no budget, we weren't paid anything, really short schedule, brutal schedule, but total creative freedom to just make what we wanted. And having gone through the Hollywood mill a couple of times, you realize just how valuable that is."

The germ of the idea for Insidious — which follows the Lambert family, headed by Josh (Patrick Wilson) and Renai (Rose Byrne) — originated from the same brainstorming sessions that led Whannell and Wan to conceive Saw. Years later when they decided to revisit it, the pair sat down and discussed the modern horror conventions they were sick of.

"The false scare, I felt like that had become a real trope of modern horror films — the friend banging on the window and the heroine turns around and gets a fright, and it turns out it's just the friend," Whannell said. "If someone's gonna bang on the window, let it be Satan, not the best friend. I think that that was part of the reason that people found it so scary. We just decided to do little things, not exactly rebellious, but just little things that we knew weren't being done."

Other innovations included making sure the audience always felt on edge by having the Lambert family attacked during the daytime. ("We wanted a feeling in the film that you were never safe," Whannell said.) He also crafted a more unusual third act in which the film ventures to the Further, an otherworldly place designed with David Lynch in mind.

"We talked about taking those aspects of a Lynchian film that scare us and putting them in a more commercial context," Whannell said. "Maybe that's the reason people found it so scary, because it was just a little bit off-kilter."

Insidious also proved to be a hit with many critics, earning more adulation than Saw had. Whannell considers it to be his and Wan's "mini-comeback," re-establishing the writer-director team as big names in modern horror, with a distinctive sensibility that separated them from their contemporaries.

"The first Insidious film felt like us kind of restaking our territory," Whannell said. "Like, OK, we're back doing what we did before. We tried the Hollywood shirt on, didn't quite fit, so now we're going back to this model."

After Insidious came 2013's Insidious: Chapter 2, which had a slightly higher budget ($5 million) and earned an even more impressive $160 million. Another sequel seemed likely.

But when Whannell sat down to write Insidious: Chapter 3, he ran into a problem. The Lambert family, who had returned as the focal point of the first sequel, had suffered too much. The only other major character Whannell felt could carry the next installment was psychic Elise (Lin Shaye), and she had been killed off at the end of the first Insidious and returned as a ghost for the second. Then he found a solution: make the third movie a prequel.

In Insidious: Chapter 3, Elise is a shell of the woman fans remember from the first two films. Plagued by her own (quite literal) demons, she reluctantly helps Quinn (Stefanie Scott), a teenage girl who invites in an evil spirit while attempting to contact her dead mother.

"[Lin] was really the driving force to go back in time. And I actually love how it turned out," Whannell said. "I loved the blank slate that going back in time gave me, because I could put her in a completely different mind-set and a different set of circumstances and not have to worry about story continuity. It's just a different time."

In another twist on the genre from Whannell, Shaye, who is 71, goes against traditional wisdom of what a horror heroine should look like. With her role in the Insidious films, she's emerged as a septuagenarian scream queen.

"I actually think it's pretty cool that someone Lin's age, someone who doesn't usually get offered lead roles in movies, gets to be the badass," Whannell said. "She's the Rambo of the film, rescuing everyone else as opposed to her being rescued."

As it turned out, Whannell didn't need rescuing either. Without Wan at the helm, Insidious: Chapter 3 does have a slightly different feel from its predecessors, but despite whatever reservations Whannell had about his own readiness, he has emerged from the experience as a confident filmmaker.

"In hindsight I couldn't have picked a better first film to direct, because of all of that prior knowledge," Whannell said. "I knew that I wouldn't know how a set goes, but at least I would have that — no one knows these characters better than I do."

As for whether or not he succeeded in his mission to create a worthy successor to the Insidious films before it, Whannell concedes that such things are up to audiences to decide. His goals, however, were clear: to make it scary, naturally, and to create the kind of thoughtful, emotionally resonant horror that has distinguished much of his past work.

"I wanted it to feel like a film that had had a lot of thought put into it," Whannell said. "My worst version of this film would have felt like a quickie, something that was slapped together for the sake of money. Sometimes when you see sequels in franchises, you get that feeling. You get the feeling that the money was right, the people were available, and it all just got put together. I'm hoping that people feel like this is really heartfelt, like whoever made it put their all into it, which I definitely did."

As he anxiously waits to see if he gets that response to Insidious: Chapter 3, Whannell is also looking toward future projects. His next film, Cooties, a horror comedy he wrote with Glee's Ian Brennan, debuts in September. It's a lot funnier than Whannell's past fare — and that's by design. Because if there's one thing Whannell is certain about when it comes to his career, it's that he wants to keep trying new things.

"Cooties was like a good introductory course because it had one foot in the horror camp and one foot in comedy, but I would absolutely love to just make an all-out comedy for sure. I feel like over the next few years, if I'm lucky enough, I want to make films in a few different genres," he revealed. "People always talk about, 'Hollywood stereotypes you, you can only do this, you can only do that. If you get known for one thing that's the only thing they want you to do.' But I feel like you can drive that perception yourself."

But no matter what genre he tries on next, Whannell will always feel the pull of horror. For all his exploration, he knows that it's a genre that will continue to embrace his originality, and one of the few where risk-taking is consistently rewarded, if not by audiences and critics, then at least by die-hard horror fans.

Perhaps that's why he's not opposed to potentially returning to the Insidious franchise — or even Saw — should the opportunity arise. The last Saw film was dubbed The Final Chapter, but those are famous last words in horror.

But for now, with Insidious: Chapter 3 behind him, he can move on to thoroughly original work. And if Whannell has his way, he'll be working as a true auteur, writing and directing something entirely of his own devising.

"This genre in particular needs filmmakers who care, not people who are dismissive about it or view it as something less than," he reflected. "It needs those auteurs."