Dillon Tate, a right-handed pitcher out of UC Santa Barbara, entered the world of professional baseball singing “Billie Jean” when he was picked in the first round of last week’s 2015 draft.

Tate was one of nine black players chosen in the first round — an increase compared with prior years. In 2014, there were four black players selected in the first round; in 2013 there were six; and 2012 brought seven black prospects into the MLB farm system, which the league said was the highest number since 1992.

“It's our hope,” MLB Senior Vice President for Youth Programs Tony Reagins told BuzzFeed News, “that these numbers will continue to rise.”

MLB has for decades struggled to recruit black American players, and the issue was reignited after the Society for American Baseball Research published a comprehensive study in 2012. The report found that, in 2012, 7.2% of MLB players were black — on average less than two players on a 25-man roster. The league had its highest percentage of black players in 1981 at 18.7%.

MLB has been slow to address this, and the result has been that young black players have less time in front of scouts, are economically shut out from playing in expensive travel teams, and have access to few scholarships for inner-city youth. The league has only recently realized that something has to be done, and officials told BuzzFeed News they have now intensified efforts to promote its youth programs that focus on recruiting black players. Whether or not these initiatives will be successful is yet to be seen.

Even MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred on the night of the draft implied that the lack of black players was an issue that has only recently been given proper weight. He called the nine first-round selections “a great improvement for us. I think it shows that some of the things we’ve been working so hard on are starting to bear a little fruit.”

Tate — chosen by the Texas Rangers as the fourth overall pick — is a product of the revamped MLB recruitment efforts. The Claremont, California, native is the highest-round pick to come out of the Urban Youth Academy, one of MLB’s youth baseball programs, which specifically focuses on underserved children in major cities. Tate began attending the Compton branch at 15, and played year-round baseball between his Claremont High School team and the MLB program. In three years at UC Santa Barbara, Tate allowed only four home runs in 149.2 innings pitched, including one from Cubs recent call-up Kris Bryant in 2013.

He officially signed with the Rangers on Friday, reportedly earning a bonus of $4.2 million.

Tate’s position is also noteworthy: Baseball researcher Mark Amour’s 2012 study showed that the percentage of pitchers in MLB who are black is around 2%, never having reached higher than 6%.

The problem, as identified by MLB and other experts who spoke to BuzzFeed News, is in the youth baseball pipeline. In a half-dozen interviews with people in youth baseball and the MLB, one word was repeated over and over: “opportunities” — as in the historic lack of opportunities for young black players.

After he was elected in 2014, Manfred decided to tackle the issue by strengthening several existing programs — specifically RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities) and the Urban Youth Academies — and appointed Reagins as the head.

The RBI program, started in 1989 in Los Angeles, is MLB’s in-house youth baseball league. Sharing its acronym with the Runs Batted In statistic, the program is divided into five groups, with tournaments for softball, junior (ages 13–15), and senior (ages 16–18) baseball. Twelve RBI players each year get a scholarship based on academics and financial needs.

The Urban Youth Academies were founded in 2006 in Compton. It provides physical facilities like fields, batting cages, and specialized instruction for young players. Kids also learn groundskeeping, scouting, and umpiring, among other skills. There are five academies across the country, and Reagins said there should be eight to ten in the next three years.

At the recent opening of the Philadelphia Urban Youth Academy, Reagins told BuzzFeed News that his team’s goal is to get youth baseball “groups and leagues rowing in the same direction.”

Under preceding Commissioner Bud Selig, youth initiatives that focused on minority and underserved youth was “important, but the emphasis was not as prominent or relevant,” Reagins said.

“MLB invested a lot internationally” recruiting players from the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico “and I don’t feel we’ve invested enough domestically,” he continued.

Steve Bandura, who coached 14-year-old pitching phenom Mo’ne Davis since she was 7, will serve as the Philly UYA manager. He has worked in recreation programs in Philly since 1989 and in 1993 he founded the Jackie Robinson Baseball League, which focuses on teaching children as much about African-American history as it does about baseball.

“When I first started here back in 1989, I was pretty shocked to see that there weren’t any programs for kids,” he told BuzzFeed News. “The kids didn’t know about baseball. There’s such a rich history of African-American history in Philly and across the country and I wanted to reconnect the kids and their families to their history in the game.”

Bandura said the Philly UYA program was 10 years in the making, an effort he said was formed by himself and the Phillies. “Once we saw the academy in Compton, we decided to try to get one here as well.”

The first UYA field in Philly opened in early June, with a ceremony attended by Phillies execs, first baseman Ryan Howard, and 92-year-old Mahlon Duckett, who played for the Negro League’s Philadelphia Stars from 1940–1949. Bandura was not in attendance, and the ground has not been broken on the indoor facility, which will be next door to the Marian Anderson Recreation Center, the longtime host of Bandura’s programs.

“The problems [with the youth baseball pipeline] are the same everywhere — it’s just a lack of opportunities for kids to find their talents and develop their talents to the best of their abilities,” he said.

The new focus of these programs is getting young black players in front of baseball scouts. “The more that we can get kids recognized by scouts ... that’s a major, major step and that’s when you start to see kids get drafted like Dillon Tate,” Arizona Diamondbacks President and CEO Derrick Hall said.

He admitted that “one kid coming through the first round of the draft is not nearly enough” to remedy the league’s abysmal number of black recruits. “But it’s a start,” he said.

One of the most significant impediments to young black players’ access to programs and scouts is the rise of the travel team. Youth baseball culture pivoted in the early 2000 to these organizations, which play showcases and tournaments that get players in front of nationwide scouts.

Rick Riccobono, the senior director of development for USA Baseball — the governing body of youth baseball in America — told BuzzFeed News that for kids, the national pastime was “once a rite of passage in this country.”

For children of affluence, that may still be the case, but the modern reality is that these leagues are expensive, specialized, and prohibitive to children whose families are without a surplus of time and resources. Highly regarded circuits are frequented by scouts, and admission for the tournament alone, said Scott Reed, general manager of the SoCal Bombers, a travel team, can top $1,000.

For many families, especially those in inner cities, the financial and time investments in travel teams are nearly impossible.

In addition to the expenses, the decline of multi-sport athletes — called specialization — has hurt baseball tremendously, said Reed. For kids of all backgrounds, basketball and football are the more popular and enticing choices.

Kids and teenagers are more likely to choose the sport their friends play. Reed said his own rosters are filled by word-of-mouth, and that fact alone could point to one reason black children are involved less in baseball. A 2013 analysis by the Public Religion Research Institute found that white Americans are likely to have social groups that are 91% white. Only 8% of a white American’s social group is black, the study found. On average, only 1% of a black American’s social network is white.

This racially insular nature of American social networks demonstrates how rosters built through personal networks in predominantly white communities lead to less minority recruiting.

Another problem in recruiting black players is how college scholarships for baseball are allocated: NCAA Division I teams can have up to 35 players on their roster, though each team is allotted 11.7 scholarships. (NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball, which has 16 roster spots, is allowed 13 scholarships. For NCAA football, some teams are allowed 85 scholarships, while others are allowed 63.)

For a child from a family without the means to pay tuition, basketball and football, are by far the more lucrative options. In 2012, black players made up only 2.6% of Division I baseball teams.

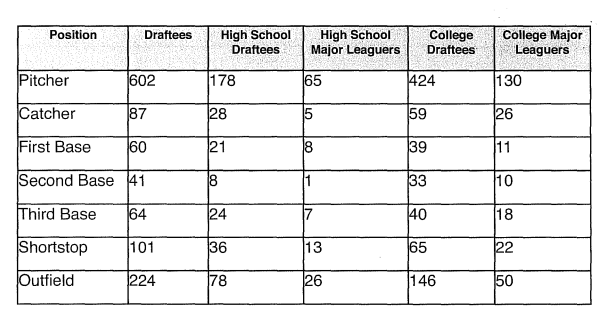

Without scholarships, paying for college is a hardship for many inner-city youths. Research shows that the surer way to the majors is still through college. In 2012, Douglas Watcher at SABR analyzed MLB draftees from 2002–2005 and found that while high school players reached the major leagues at slightly higher rates than college players (33.5% compared with 33.1%), college players made up the vast majority of those drafted at all positions. Over the course of the three years, for instance, Watcher found that 424 pitchers had been drafted from college (130 made it to the majors) compared to 178 pitchers drafted from high school (with 65 making the big leagues).

Investing in the future generation is as much business as it is altruism, Hall said.

“For us to survive, our longevity is really dependent on children playing the game and getting interested in the game. Then, hopefully, they’re fans for life,” Hall said.

Hall wouldn’t say if he had specific goals for the number of black players he would like to see making it from the RBI and UYA to the major league, but said “ our clubs should really be a reflection of what our market demographics are.”

“What we do now is look at the high mark, and when you’re down now to 8%” — referring to the Society for American Baseball Research’s 2012 report — “we just have to see improvement there,” Hall said.

David James, the Senior Director of RBI, said the change won’t happen overnight. “It took a long time for that number to drop,” he said, “and will take a long time to turn it around.”