WASHINGTON — For the global LGBT movement, 2013 was a year of extremes.

Victories on marriage in countries like the U.S., U.K., and France signaled a major tipping point for gay rights activists. After decades of losing major battles, it seemed they had won the argument that gays and lesbians were entitled to full citizenship in the democracies long regarded as the standard-bearers for human rights worldwide. (Trans activists also made some gains in places like California and the Netherlands, though the same level of consensus does not appear to have formed in support of their rights.)

Which is perhaps why passage of Russia's so-called "gay propaganda" law — which technically prohibits promoting "nontraditional sexual relationships to minors" — struck a deep chord with Western activists. Musician Melissa Etheridge spoke for many American gays and lesbians when she said at a recent fundraiser for Russian LGBT organizations: "All of us [in the U.S.] who have gone that journey [toward equality], when we see what's happening in Russia [we say], "No no no no. We are never, ever, ever going back."

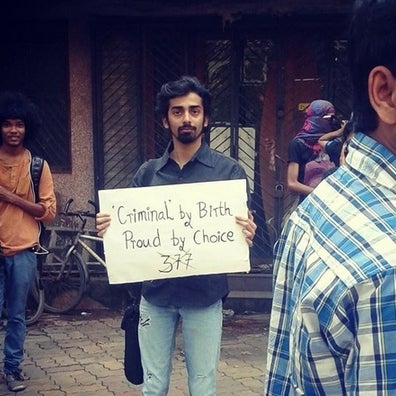

Bad news for LGBT people grew as the year drew to a close. The Supreme Court of India reinstated a sodomy law, recriminalizing same-sex relationships in a country home to 1.2 billion people. Uganda's parliament unexpectedly passed its long-pending "Kill the Gays" bill (though penalties were revised down to life in prison in the final version), while Nigeria — the world's seventh largest country — is on the verge of enacting the world's broadest laws targeting LGBT rights.

"Australia, India, Uganda, Russia, and now this," Ken Kero-Metz, foreign policy fellow with the U.S. Congressional LGBT Equality Caucus, said in an email to BuzzFeed. "Great year in the U.S., but globally? Turning out to be one of the worst."

While a global human rights debate is not reducible to a scorecard, this statistic is instructive: While 18 countries, home to more than 10% of the world's population, now recognize same-sex marriage, 77 countries still outlaw sodomy.

In some cases — Russia is the clearest example — the crackdown on LGBT rights was a calculated political move by national leaders to frame the nation in opposition to the West. But in other places, like India, Zimbabwe, or Singapore, internal legal and political disputes explain a lot more about the retreat from LGBT rights than international dynamics. Yet the language in which the debates are fought reflect the way the fight has been globalized: LGBT activists use the language of universal human rights, while their opponents respond by claiming they are fighting to preserve local traditions and religious beliefs against "foreign" attack.

Here is a review of some of the most important global LGBT rights stories of 2013.

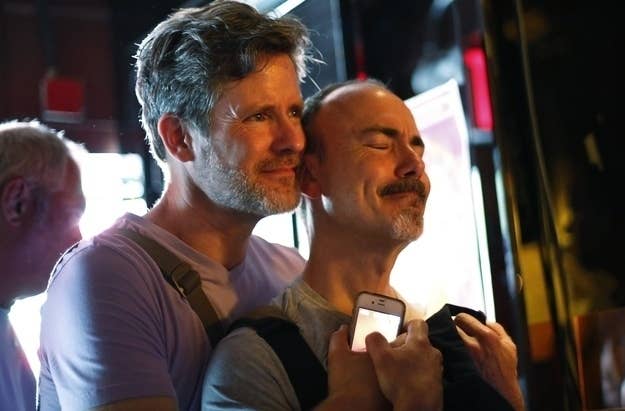

Marriage on the March: U.K., France, U.S. Brazil, Mexico...

Britain and France's votes to enact marriage equality, alongside the U.S. Supreme Court ruling ordering federal recognition of same-sex marriages performed under state law, were the clearest sign that the LGBT rights movement had entered a new era. Less noticed in the United States was the news that Brazil's National Council of Justice also issued a ruling establishing marriage equality in May. And judges in several Mexican states granted marriages to same-sex couples following a ruling late last year from Mexico's Supreme Court.

...and Colombia.

Judges have also begun marrying same-sex couples in Colombia under a 2011 Constitutional Court ruling that took effect in June 2013. But ambiguities in that ruling have touched off a new round of legal fights that mean it's just a matter of time before the top court has to say once and for all whether these marriages are valid. In the mean time, the constitutional court endorsed the rights of LGBT people to adopt in two important cases.

Australia, Croatia, and Zimbabwe? Not so much.

The hope for a change to Australia's national marriage law faded when marriage-equality supporter Kevin Rudd lost the prime ministership to Tony Abbott in a September election. The Australian Capital Territory — the jurisdiction that includes the capital city, Canberra — went ahead and passed a bill legalizing same-sex marriages on its own. After four days of weddings, the High Court put a stop to them, saying that federal law trumped the ACT's provision.

Voters in the Balkan nation of Croatia voted to amend the country's constitution to ban same-sex marriage on Dec. 1. This was a bit of an embarrassment to the country, whose LGBT rights record was under close scrutiny in the run-up to its joining the European Union this summer.

Voters in Zimbabwe also voted to ban same-sex marriage when they ratified a new constitution in March. President Robert Mugabe had used the issue of same-sex marriage as a cudgel against opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai during negotiations over the draft. (Tsvangirai was less hostile to gay rights than Mugabe, but he had never endorsed marriage rights.) Mugabe's Zanu PF party mobilized anti-gay sentiment in the elections that followed the constitution's ratification. On June 7, for example, men armed with hammers believed to be associated with the government's youth militia and ransacked the offices of Gay and Lesbians of Zimbabwe.

The British Empire strikes back in India and Singapore...

Though the United Kingdom has adopted marriage equality, many of England's former colonies cling to the sodomy laws they inherited from their former ruler — Queen Victoria continues to rule the personal lives of her former subjects more than a century after her death.

India's Supreme Court effectively recriminalized same-sex relationships earlier this month when it upheld the constitutionality of the sodomy provision, known as Section 377. The law had been suspended since the Delhi High Court struck it down in 2009.

In October, a judge in Singapore upheld the country's own version of the same colonial-era law — known there as Section 377a — in a ruling that also claimed homosexuality may be something that can be changed, apparently on the basis of a single study in which the researchers surveyed Singaporeans' attitudes toward homosexuality.

...and in Uganda...

Uganda is also a former British colony, and its long-proposed extreme version of a sodomy law — the so-called "Kill the Gays" bill — came off the shelf on the last day of the parliament's 2013 session. Last year, Speaker Rebecca Kadaga had called for passing the law as a "Christmas gift" to the Ugandan people; this year she was determined to deliver, even if it meant violating parliamentary procedure.

Following a vote on Dec. 20, the legislation now heads to President Yoweri Museveni. The final version reduced the maximum punishment from death to life imprisonment. An American judge ruled earlier this year that the proposal is so extreme that an American supporter of the initiative, Scott Lively, can be tried for crimes against humanity in U.S. courts.

...and Nigeria.

Nigeria, another former British colony and the world's seventh largest country, is also on the verge of enacting a harsh anti-gay law. And while its penalties are not as severe as those in the Ugandan proposal, it has broad aims beyond increasing the penalties for same-sex relationships.

The proposal, known as the "Anti Same-Sex Marriage" bill, would not only send same-sex couples to jail for performing a wedding ceremony, but also makes it a crime to support LGBT rights in any way.

The bill has been in process since 2006, and both the House and Senate had passed versions. On Dec. 19, the Senate passed a compromise version of the bill, and it could soon be on the desk of President Goodluck Jonathan.

And then there's Russia.

Passage of Russia's law banning the "promotion of nontraditional sexual relationships to minors" had ramifications far beyond its borders, and President Vladimir Putin probably wanted it that way.

The law enabled Putin to shore up his power by mobilizing opposition to the West and stoking fear at home. Enacted months before the Sochi Olympics, it was guaranteed to generate months of confrontations around this issue, in which Putin could be seen standing up to the West. The government has been eager to fan the fear of a "homosexualist invasion" within the country, warning of the pink peril in propaganda on state television.

As the situation has deteriorated for gays and lesbians inside the country — with vigilante violence just as big a fear as the state's crackdown on their political rights — some of Russia's allies have exported its approach to cultural battle with the West. In Ukraine, Armenia, Moldova, and other countries that have been courted by the European Union, forces who favor alignment with Russia have used opposition to LGBT rights to try to scare public opinion away from closer ties to their Western neighbors.

So what's ahead?

The Russia story is far from over, of course. With the Olympics set to begin in February, it will continue to dominate the discussion of LGBT rights as we head into 2014. And when international attention fades after the games, there is concern among human rights advocates that the LGBT activists who have helped mobilize international disapproval could find themselves in jail.

There are also bright spots for the LGBT rights movement. Civil union proposals are under serious consideration in both Thailand and Vietnam. Chile just elected a president who says she supports same-sex marriage, and an organized push is being made for civil unions in Peru, one of South America's most conservative countries.

But the world seems to be pulling in two directions on LGBT rights. And the battle is becoming increasingly international as LGBT rights become more central in international affairs just as the gulf widens between nations.