If you're in the mood for a jaw-dropper of a '70s action cinema specimen featuring men climbing a mountain: The Eiger Sanction (1975, Clint Eastwood)

Climb that high up and it does funny things to your brain. Clint Eastwood’s espionage-on-a-mountain thriller The Eiger Sanction is, among other things, a daunting feat of old-school technical bravado. Eastwood stars as an art professor who used to moonlight for the government as an assassin who's been called back for one last job. Said job involves climbing a large mountain in Switzerland. The mountain-climbing action, most of it confined to the film’s second half, is terrifically rendered. Eastwood’s unfussy style of filmmaking, coupled with his insistence on making the climb look real by actually climbing a mountain, lends a slowly mounting tension to the rising action — the team of mountaineers creep up ever so slowly until, in a split second, something goes wrong. The film makes excellent use of its judicious location shooting — these are some gorgeous vistas and they’re wondrous to look at, even when Eastwood is hollering, “You AAAAASSSSSHOOOOOLLLEEE!” over them.

About that. There’s no way around it, so might as well barrel on through: In addition to being beautifully shot and satisfyingly tense, The Eiger Sanction is offensive, tasteless and completely nuts. The screenplay doubles down on laconic manly cool and ‘70s tough-guy attitude, piling up equal-opportunity offense and vulgar witticisms so high that the film breaks from sanity and flies off into the ether. No film with all its marbles intact would have an expository scene delivered while an albino is having his blood drained and replaced. (“With what?” snarls Clint.) A film with proper bearings wouldn’t have Clint say, “Yeah, I thought I'd given up rape but I've changed my mind,” and mean it as a charmingly roguish pick-up line. A film with both feet on the ground wouldn’t have a screamingly fey secondary villain with a little lapdog pointedly named — seriously — Faggot. In its combination of toxic sexual politics, striking quick-release action and unexpected cynicism towards global gamesmanship, The Eiger Sanction is a movie to watch with mouth permanently agape, wondering what amazement will stumble around the next corner.

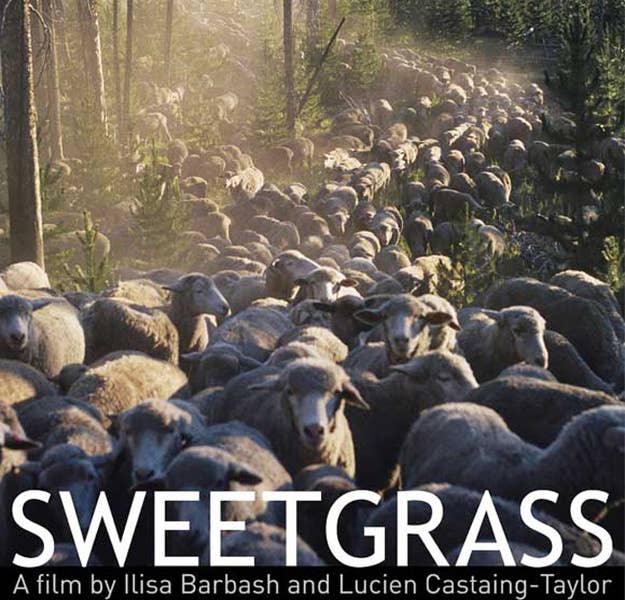

If you're in the mood for a contemplative documentary featuring men ranching on a mountain: Sweetgrass (2010, Ilisa Barbash & Lucien Castaing-Taylor)

Sheep move in herds, thoughtlessly. Everyone knows that, right? But to watch Sweetgrass, an engrossing documentary about sheep-herders from Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor is to realize that description is inadequate. There’s a difference between moving thoughtlessly and without thought — the former implies daftness, wandering without a destination while the latter implies subservience to an implacable and unerring natural instinct, and it’s the latter we see on display here. The sheep are easy to manage when it comes down to an individual basis (we see ranchers pinning down unruly sheep and slipping dead skins over orphaned lambs in mostly successful attempt at bending the animals to their wills). But as a group, they stop being animals and become a force of nature, an undulating river of wool. There’s a striking sequence early on where the herd makes a wrong turn and gets marooned in a valley; the ranchers swear and shout and try to get the group moving, but they might as well be trying to uproot and replant the trees that surround them.

Clearly, these guys lead a tough life. Rather than tell you about this via talking-head testimonials or sympathetic narration, however, Barbash and Castaing-Taylor choose a more impressionistic approach meant to immerse you inside this world, with great emphasis on the arduous everyday tasks that have to be done just to assure the survival of the flock. The photography alternates between you-are-there handheld close-quarters shooting and enormous panoramic shots that highlight both the beauty and the vastness of the area, creating a clear contrast between the grueling routine of the men and the placid indifference surrounding them; meanwhile, the especially effective sound design is filled to the brim with echoes and howling wind and endless amounts of bleating. (I had no idea sheep had so many variant sounds in their sonic repertoire.) The effect is that of a constant sensory wearing-down, a forced exhaustion, so that when near film’s end one rancher abruptly breaks down and cuts loose with a cathartic blast of vituperative profanity, we understand exactly where he’s coming from. It’s a risky tactic, but ultimately rewarding.

If you're in the mood for a spry, fun costume drama featuring a man as big as a mountain: The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933, Alexander Korda)

If you’re looking for a proper history lesson, this is not going to be your cup of tea. However, if you’re merely looking for a rollicking comedy of ill manners in royal garb, you’ll be right as rain. It chooses to start paying attention to Henry’s exploits right before Anne Boleyn loses her head and sprints through the subsequent four marriages in a brief ninety-three minutes. The king hops from bed to bed, women come and go and the waitstaff mills and buzzes, tossing around knowing double entendres and constantly talking about the goings-on of Henry and his libido in a way that lays bare the quiet irony of the title.

Henry, in fact, is all anyone talks about. Even in the rare moments when he’s not on screen, he still holds sway over the proceedings. For a man who inspires that level of dominance, you need a larger-than-life performance. Charles Laughton’s Henry, then, is precisely what Korda needed to push this over — ever the outsized performer, Laughton delivers a full-throated, ruddy portrayal of a man defined (at least in this script) by his titanic and fickle appetites. When Henry, messily devouring a turkey, proclaims, “Refinement’s a thing of the past… manners are dead!” the irony is impossible to miss, but Laughton makes it work through solid delivery and terrific body language (tossing half-eaten portions over his shoulder is a great gesture). Yet he knows when to rein it in a bit for maximum effect; while Henry’s exaggerated repulsion upon meeting the Germanically dowdy Anne of Cleaves (Elsa Lanchester, in a small-but-delightful comedic bit) is funny, his careful, halting attempts to explain the duties of the wedding night to her is what really kills. (The relief with which he delivers the line, “You’re the nicest girl I ever married,” is the perfectly delicious topper.) The Private Life of Henry VIII is a film that, in its cheeky way, prints the legend, puts bodice-ripping scandal ahead of politics and reduces a fascinating historical figure to a gluttonous lecher. And I don’t see a damn thing wrong with that.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.