Bet Olson was 16 years old when she realized she wanted to adopt a child someday. Bet, who was raised in a Christian family outside Chicago, was attending a youth group service at Willow Creek Community Church, a megachurch in South Barrington, Illinois. A young man started to talk about adoption. “He talked about how the story that God has for his people is to adopt them as his own,” Bet recalls. “That this is God’s character, to bring love and redemption. He talked about how he was adopted and what a difference that made in his life. I soaked up every word.”

Nearly 20 years later, Bet and her husband, Erik, live in a small green house on a quiet road in Elgin, Illinois. When I visited, it was early March, that time of year in the Midwest when you can wake up to a 70-degree day or to snow. This day was somewhere in between — overcast and in the low 40s. The Olsons’ children, Zain, 7, and Tesfa, 6 — Tess for short — had just gotten home from school and were playing in the sunroom at the front of the house. Tess was talking about her kindergarten class, where she had just been named Kid of the Week. “That means everyone’s going to say good things about me!” she said.

Bet and Erik adopted Zain and Tess from Ethiopia. “People kept telling me I would change my mind” about adoption, Bet said. “And I just said no. I felt so strongly that this was my calling.”

Bet and Erik began the process of international adoption in 2008, after three years of marriage. Following a home study and over a year of waiting, they were matched with Zain in August 2010. “For the longest time we had two pictures, and we would just look at those two pictures and we just fell in love with this kid,” Erik said. They flew to Ethiopia in November 2010 to meet Zain, and then waited six weeks in Addis Ababa for all the visa paperwork to go through in the US before they were allowed to bring him home, when he was 7 months old. They came back just before Christmas as a family.

Being adopted was akin to a pre-existing condition.

But there were complications ahead. Because the Olsons were members of a Christian health care sharing ministry, rather than a traditional insurance plan, some of Zain’s health care costs wouldn’t be covered the way a biological child’s would. Being adopted was akin to a pre-existing condition.

Since 2007, Bet and Erik had been members of Samaritan Ministries, one of a number of Christian health care sharing ministries in the US that take the place of traditional health insurance by pooling and redistributing members’ money each month. They joined when they were both working for a Christian nonprofit founded by Bet’s dad, where they had to personally raise funds from donors to cover their own salaries. Raising more than that to pay for insurance through the organization as well would have been a burden, so they started to look for creative solutions.

Some of their friends from church recommended Samaritan, which is based in Peoria; Bet and Erik looked into it, liked what they saw, and joined. “I love the idea of sharing each other's burdens and helping each other out,” Erik said. And up to a point, Samaritan worked for the Olsons. Each month they wrote checks to the name Samaritan sent them. Sometimes they prayed for the recipient; sometimes they forgot. Outside of an incident where Erik broke his toe, Bet and Erik never submitted a need for themselves. But when their children had needs, things were different.

Before Bet and Erik could bring Zain home, in 2010, they had to show proof of insurance coverage. They got a letter from Samaritan attesting to their membership, and planned to add Zain to their Samaritan coverage once they were back in Illinois. According to its guidelines, Samaritan, like other health care sharing ministries, does not share in costs for “any physical condition which the adopted child has prior to the adopted parent being legally responsible for the child’s expenses.” Essentially, all conditions an adopted child has prior to adoption are considered pre-existing. Had the Olsons adopted a child with Down syndrome, or a neurological disorder, they would have incurred all the costs related to living with that condition.

Luckily, Zain was healthy. But Bet and Erik took him to the doctor for a general checkup when they arrived home, and as a precaution the pediatrician ordered a panel of blood tests recommended for international adoptees by the University of Minnesota. The tests cost around $6,000, a sizeable portion of their annual income, and Erik and Bet set about submitting their need to Samaritan. “God blessed our family by giving us a beautiful boy from Ethiopia!” they wrote on their need processing form to Samaritan. “We had to have some medical testing done. All recommended international adoption medical testing came back normal and healthy. Praise God!”

Samaritan declined to share their need.

“We went to Samaritan Ministries with the need and they said, ‘This is pre-existing,’” Bet said. “We said, ‘What? What do you mean by pre-existing?’” What Samaritan meant is still unclear, because the ministry became fairly unresponsive to the couple in early 2011, when all of this was happening. The only communication the leadership provided was to explain that they would not share this cost, but that Bet and Erik could list it as a "special prayer need" in the monthly newsletter, where members could pray for them and send money if they chose to do so (six or seven people did, Bet said, all less than $50 apiece). Bet and Erik scrambled to get coverage for Zain under Medicaid in Illinois, ending up in an income-based tier where coverage would cost them $70 per month. They were able to negotiate Zain’s bloodwork costs down to about $3,000, and worked out a payment plan with the hospital.

Even through this disruption, the Olsons stayed with Samaritan, both because the price was right (around $350 per month for the two of them) and because they still believed in its mission. Samaritan was “so biblical,” Bet said, “an amazing way to show what the kingdom of God could look like.” But, she said, “it was missing this huge piece.”

For Christians looking for a way to opt out of an expensive health insurance market that they see as profit-driven, intruding on their personal freedom, and indifferent (at best) to issues of abortion and the sanctity of life, health care sharing ministries may seem like the perfect, providential solution. These ministries now legally satisfy the individual mandate of the 2010 Affordable Care Act, and have expanded rapidly since its passage. But there are serious drawbacks lurking below the surface. These ministries’ policies replicate some of the most significant problems with insurance that the ACA was intended to address in the first place, and come with their own unique risks for consumers.

Legally, ministries are not insurance providers, so there are no laws regulating who they must accept as members or which costs they cover — just a social contract between their members. Pre-existing conditions can disqualify someone from membership, while lifetime reimbursement caps and religious restrictions might mean that some members’ medical needs aren’t, in fact, reimbursed. These ministries are, to many, a straightforward blessing: a cheaper alternative to insurance and an extra assurance that their money is not going toward abortions. Many of the members I’ve spoken with are very happy with the care they receive and have found these ministries to be a source of security and community. But for others, like the Olsons, the relationship is not so simple. That’s because the stated Christian mission of these ministries doesn’t always match the reality of what they offer in the face of real, painful need.

The health care sharing ministry landscape is dominated by five major players with the largest memberships and highest revenue, spread across the country and across Christian denominations. Samaritan Ministries (in Illinois), Christian Healthcare Ministries (in Ohio), and Medi-Share (in Florida) are the three large evangelical operations. (Dozens of similar ministries exist across the country, mostly smaller and more localized.) Ohio’s Liberty HealthShare is Mennonite, a denomination traditionally committed to pacifism and dialogue. Solidarity HealthShare, founded in 2015, is Catholic, and partnered with another Mennonite aid group in Ohio to be grandfathered into the ACA exemption for sharing ministries, which required that they exist before 1999. All ministries require members to sign statements of faith. Liberty’s is the broadest, and could theoretically be signed by people of varying religious backgrounds, but the others are fairly stringent. Many require regular church attendance, and Samaritan Ministries requires the signature of a pastor or church leader attesting that prospective members meet all requirements.

Each ministry operates slightly differently, but the basic premise remains the same: Every month, members pay a certain amount (their “share”) into the ministry. When a need arises — say you break your leg, or get diagnosed with lung cancer, or have a baby — you submit your bills to the ministry’s office and you receive payments for the total amount you owe, usually in the form of checks or direct deposits from various members. Some ministries hold the funds in an online escrow account; others have members mail their checks directly to the other members. Shares out are published by the ministries each month, so you can see that your $405 is going to, say, Irene in Idaho who recently had a hip replacement.

Most health care sharing ministries were born out of tragedy and frustration with the health care system in the US. Chris Faddis, the cofounder of Solidarity HealthShare, found himself at the end of his rope when his first wife was diagnosed with late-stage colon cancer in 2011. “She was so far into her diagnosis that there was not much that traditional chemo by itself would offer,” he told me. “So we found ourselves in a situation where we had to raise money.”

His connections in the church world helped them raise over $125,000, but the experience left him wondering what less connected people could rely on. “At the end of that I felt like I was supposed to be helping other people find a sustainable way that we can do health care, where people are taking care of each other,” he said. A number of the people I spoke with in reporting this story had turned to online fundraising to cover expenses that traditional insurance wouldn’t take care of, but crowdsourcing health care is the opposite of a sustainable solution. It makes sense, after an experience like Faddis’s, to want to create an entirely new system — although it is worth noting that had his wife been diagnosed and then tried to join Solidarity, her disease would have been considered a pre-existing condition, and she would have been unable to share any of her cancer-related costs.

"Financially, it was the best route for us to go. It seems to me, in some ways, like a really well-kept secret.”

These ministries are attractive to consumers for a number of reasons, but the biggest draw is likely their affordability. The individual health care marketplace can be hard to navigate, and it’s often difficult to get a clear idea of what coverage will cost, although tools like the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Health Insurance Marketplace Calculator seek to make that easier. There, we can see that a young family of five making a combined annual income of $80,000 in Cleveland would pay $608 per month in premiums; the same family making $120,000 in San Francisco would pay $1,450 per month.

Monthly costs for health care sharing ministries vary, but are relatively low: A two-person family pays $440 per month with Samaritan Ministries and a family of three or more pays $495. A Gold membership in Christian Healthcare Ministries costs $450 a month for a family, one dollar more than a family pays for a Complete membership with Liberty HealthShare. So, for some families, these ministries represent enormous savings — or seem to. They don’t cover everything traditional insurance would; the cost of prescriptions and preventive care is rarely shared, and lifetime caps mean that sharing won’t go beyond a certain amount per illness, usually between $125,000 and $250,000, unless a member joins a “catastrophic savings” program. Still, the low monthly cost is enormously attractive for most members.

For Becky Boggs, a retired administrative assistant who lives in Lincoln, Illinois, that made all the difference. “Huge savings for us, huge,” she told me. “I wasn’t working and my husband was working at a church and he wasn’t making a ton of money. Financially, it was the best route for us to go. It seems to me, in some ways, like a really well-kept secret.”

These ministries are generally much smaller than the biggest insurance corporations, and operate as nonprofits. Many of the members I spoke with appreciated the fact that their hard-earned money isn’t going to line the pockets of an ultra-wealthy CEO. Samaritan’s CEO, Ted Pittenger, took home just over $184,000 in 2014, the last year for which the ministry's information is available. Dale Bellis, the executive director of Liberty HealthShare, earned a salary of $110,829 in 2015. Compared with insurance CEOs, that’s a drop in the bucket — in 2015, the CEOs of Aetna and Cigna both earned $17.3 million.

Boggs likes that her monthly Samaritan payment goes directly to the person in need. “My check never goes to Peoria,” she said.

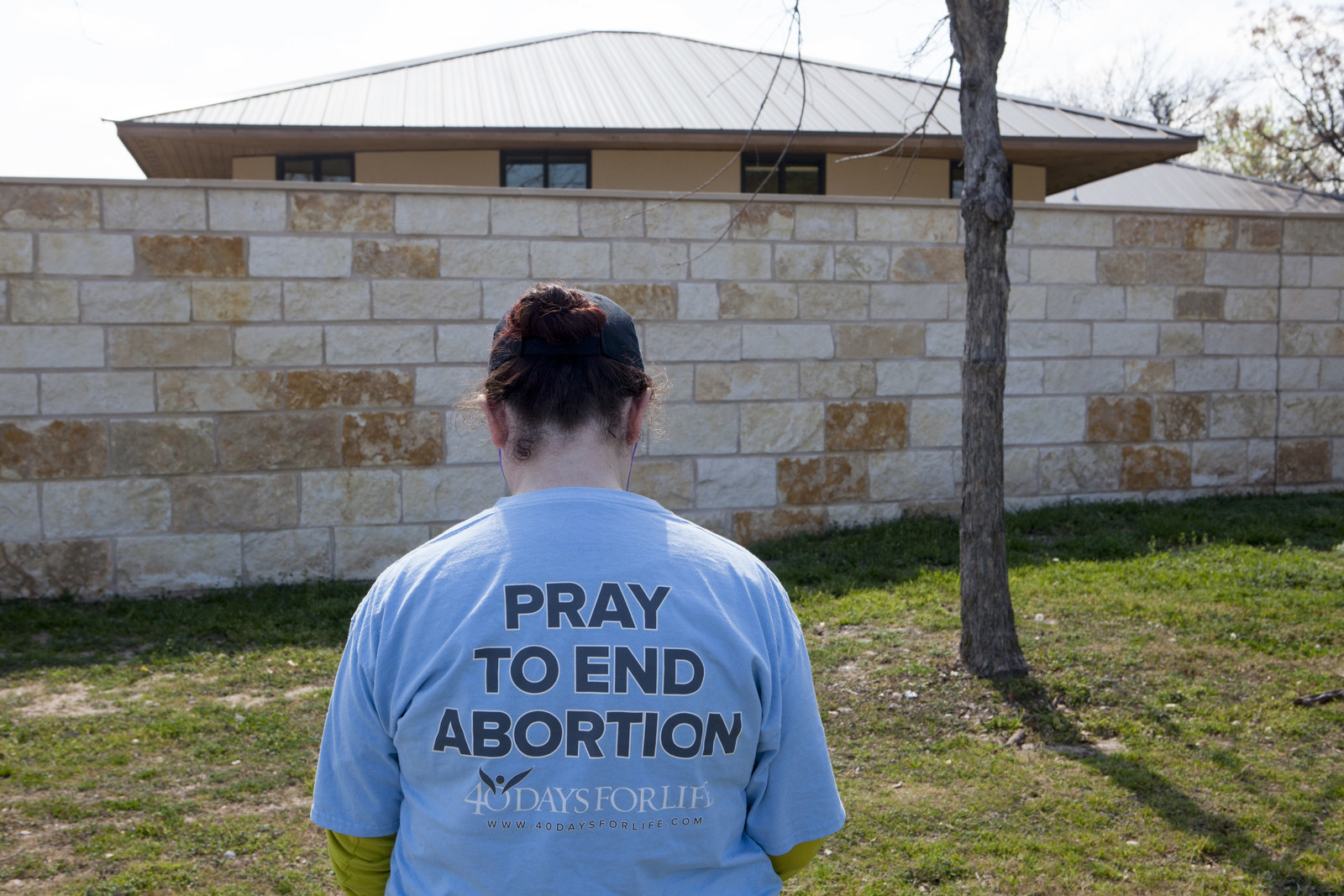

Another big draw for ministries is that they don’t cover abortion or birth control, so members with ethical objections can be certain their money isn’t funding procedures or medication they don’t support. “Are you working and praying for abortion to end while your health insurance company is using your premiums to pay for abortion and abortifacient drugs?” asks one Samaritan Ministries brochure. “Your company’s policies may not mention abortion. They might say ‘women’s services’ or ‘reproductive treatments’ or ‘birth control.’ The result is the same, no matter what they call it.” All five of the major health care sharing ministries — Samaritan, Medi-Share, Christian Healthcare Ministries, Solidarity HealthShare, and Liberty HealthShare — make explicit statements in their promotional material about not sharing in needs related to abortion.

Ultimately, ministry members seem to find value in the human connection of sharing their health care needs with fellow Christians, often in stark contrast to the impersonal nature of traditional insurance. Boggs had to have some testing done for a heart issue, and after submitting her need, she and her husband received notes in the mail along with their checks. “There was a whole family, six kids or so, and the parents had let the kids make a little card. They all drew little pictures on it and signed it. We also get these notes from people that say, ‘Hey, we’re happy to be able to share in your medical need for the month.’”

Brandon Jones, a 38-year-old pastor from rural Herreid, South Dakota, agrees. Jones supplements his income with some online teaching. He and his wife and three children are members of Samaritan Ministries. (They also take in foster children, who are all covered through Medicaid.) It was the personal touch, along with the affordability, that attracted him to Samaritan. “I send checks out each month to people across the nation, hear a little bit about their story, pray for them,” Jones said. “And when we have a need, that’s reciprocated.”

Because health care sharing ministries aren’t legally insurance companies, they don’t technically offer “coverage,” instead shifting monies from one member to another to “share” costs. But lobbying efforts earned them protected status under the Affordable Care Act, allowing their members to remain exempt from the individual insurance mandate the ACA established — provided that the ministries existed prior to 1999, underwent annual financial audits, and retained members even after they developed medical conditions. And membership of health care sharing ministries has seen explosive growth since the passage of the ACA in 2010.

Joel Noble, Samaritan Ministries' director of public policy and the vice president of the Alliance of Health Care Sharing Ministries, told me that its three member ministries (Samaritan Ministries, Medi-Share, and Christian Healthcare Ministries) have a total membership of just under 900,000 individuals, up from about 565,000 in February 2016. Liberty HealthShare has 145,000 members; in 2016, it grew by more than 200%. Medi-Share, the Florida-based ministry, has grown from 35,000 members in 2010 to more than 290,000 members in April 2017.

Samaritan Ministries saw its revenue increase exponentially, from $6.6 million in 2013 to over $34 million in 2015. Liberty HealthShare has seen even greater growth — its revenue was $1.9 million in 2014, shot up to $10.9 million in 2015 and, according to the ministry, exceeded $36 million in the the final 2016 audit.

That’s likely due to a combination of factors: Affordability (compared to plans available on ACA exchanges) has been a big draw for new members, as well as the appeal of belonging to a community that shares similar values. The ACA requires insurers to fully cover some forms of birth control, for example; Christian sharing ministries have no such obligation. Some people simply didn’t like feeling compelled by the government to purchase insurance. In a post about the ACA, one evangelical blogger wrote, “When we do not have the real freedom to choose if or how we want to spend our earnings and care for our own person and family, we are in bondage.” To people who feel similarly, health care sharing ministries present themselves as not only a feasible option, but a desirable alternative.

But there are significant differences between what insurance companies and sharing ministries are legally required to offer consumers. “In general, these arrangements are not regulated as insurance, and they appear to embrace many of the discriminatory practices that health insurers used to employ against sick people and that the Affordable Care Act tried to eliminate,” said Kevin Lucia, a policy analyst and professor at Georgetown’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. “It appears to me that the health sharing ministries are designed in a way to discriminate against sick people. They typically don't always cover pre-existing conditions and often have gaps in critical services, such as coverage for mental health services.”

A pre-existing condition was a problem for Tara Owens. A spiritual director in Colorado, Owens suffered a heart attack in April 2010. The next month, her husband lost his job and they were soon left without insurance. “I was not a high-risk patient,” she said. “When I had the heart attack, I exercised every day, I didn’t have high blood pressure or cholesterol, there was no history [of heart conditions] in my family.” She and her husband had heard of health care sharing ministries and applied for membership in Medi-Share. It accepted Owens’ husband, but not her.

"We would love [for] health care sharing ministries to get big enough that pre-existing conditions are no longer an issue."

Owens eventually got coverage through Colorado’s Rocky Mountain Health Plans, but the experience rankled. “I had the question for this program, ‘Christian how?’” she told me. “In part because they wouldn’t even listen to me; there was no discussion of my case. Which made it feel like another corporate experience, where I’m a number rather than a person.”

A spokesperson for Medi-Share told me that the ministry’s guidelines changed in 2013 (three years after Tara Owens applied), and “pre-existing conditions are no longer a barrier to membership.” But costs associated with pre-existing conditions still may not be shared.

Health care sharing ministries try to keep costs low for their clients, and, according to Solidarity founder Faddis, sharing the costs of pre-existing conditions would be prohibitive. “We would love [for] health care sharing ministries to get big enough that pre-existing conditions are no longer an issue,” he said. But “at this point in the game, that’s almost as lofty a goal as Elon Musk getting to Mars.” Which, Faddis acknowledges, could happen in the not-too-distant future — just not right now.

Ministry members often pay their medical bills out of pocket and wait for reimbursement; they are also encouraged to negotiate discounts with their providers. Bet Olson did this when she was with Samaritan: “I remember saying, ‘We don't have insurance. Do you have a cash rate?’ Sometimes that would drop [the bill] by, like, two-thirds.” The website for Christian Healthcare Ministries recommends a similar strategy: “Insurance companies regularly negotiate prices and you can, too.” If a patient doesn’t get a discount of at least 40%, Christian Healthcare Ministries recommends working with its patient advocates to coach you.

There is little to no cost sharing for chronic conditions or preventive care. If you are diabetic, for example, you will most likely have to cover the cost of insulin on your own. (The price of insulin, which has to be refrigerated and lasts six months at most, continues to rise, and can be as high as $900 per month.) Visits to physical therapists or occupational therapists are usually capped (for instance, with Medi-Share you can share “up to 20 visits combined per referral”), and mental health is almost never shared.

Jones, the South Dakota pastor, was reluctant to join Samaritan at first. “I’m more of a traditional person,” he said — Jones worked at Blue Cross Blue Shield and Farmers Insurance before he was a pastor — but has been happy with the experience so far. In the last few years, he’s even acted as an ambassador, encouraging others to join if they are struggling to pay insurance premiums. But, Jones said, his family doesn’t always make preventive care — which isn’t covered — a priority. “I’ve had trouble convincing my wife to make the expense” of regular gynecological checkups, he said. “I don't think she's really seen a specialist in a few years now.”

And then there’s the question of adoption. Under federal law, insurance companies must treat an adoptive child as a “natural” child from the time he or she is placed with the adoptive parents, and cannot deny coverage because of pre-existing conditions. Health care sharing ministries, however, make their own rules.

As Zain got older, Bet and Erik Olson decided to begin the process of adopting again. In November 2012, almost two years after they went to Ethiopia to meet Zain, they were matched with their daughter, Tess, a vibrant young girl with boundless energy. They met her in April 2013, she turned 2 in May, and they brought her home in June. This time, they knew there would be some challenges: Tess had received conflicting test results in Ethiopia, indicating the possibility of a blood disorder.

Bet and Erik called Samaritan. “We knew what the answer was going to be,” Bet said, “but we just wanted to challenge it again.” As they expected, Samaritan said that it wouldn’t share any needs related to Tess’s bloodwork. Bet and Erik decided to appeal. They wrote an email to the leadership of Samaritan Ministries, asking the organization to reconsider its stance.

“With all of its faults, our government still shows glimmers of compassion,” Bet and Erik wrote. “A law was put into place that made sure adopted children were treated by health care companies without discrimination. A health care company cannot deny coverage to an adopted child that it would have otherwise provided for a biological child.” Later, they wrote, “I find it interesting that you do not want to fall under this law — which I feel is one that protects human rights — but then when it comes to ObamaCare, you want to be considered an exclusion.”

The Olsons also asked Samaritan to consider that to be anti-abortion means to be pro-adoption. “As we become more like Christ, we care more about what he cares about," they wrote. "I feel he gives us a mandate to care for orphans and widows. It is not an option in the Kingdom of God, but rather a command.”

“With all of its faults, our government still shows glimmers of compassion."

The command that Erik was referring to is peppered throughout the Bible, most pointedly in James 1:27: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress, and to keep oneself unstained by the world.” Practicing Christians are twice as likely to adopt compared with their secular counterparts. There are no statistics for how many evangelical Christians in the US adopt each year, but since the mid-2000s adoption has been the subject of evangelical conferences, ministries, and initiatives designed to “defend the cause of the fatherless,” as a verse from Isaiah says. In fact, the recent “evangelical orphan boom” has been criticized for prioritizing parents’ desires over children’s well-being. Bet and Erik are aware of these criticisms and have worked to understand them. “I have been made more aware of my white privilege,” Bet said. “I want to use that awareness to educate people.”

The number of international adoptions in the United States is declining overall (from 19,601 in 2007 to just 5,370 in 2016) as other countries increase regulations, but the Christian interest in adoption is going strong. And while each family is different, it seems likely that the Olsons are far from the only parents in the US who might find that the medical care their adopted children need isn’t considered essential by their Christian health care sharing ministry.

Tess, with her special needs, would require some care that Zain had not, and Bet and Erik felt it was incumbent on them to encourage Samaritan to raise its standards. “Her name is Tesfa,” Bet said. “That’s the Amharic word for ‘hope.’ There’s no hope in saying, ‘But not special needs.’ That’s where most hope is needed.”

The Olsons were told that their letter would be passed along “to higher leadership” at Samaritan. After that response, they waited, but didn’t hear back from anyone else. “It was crickets,” said Bet. “They never did give us an answer.” (Samaritan declined requests to comment for this article.)

Health care sharing ministries remained in business after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act only because of extensive lobbying by two groups that work on their behalf: the Alliance of Health Care Sharing Ministries and the National Coalition of Health Care Sharing Ministries. These organizations spend hundreds of thousands of dollars annually, seeking to “return health care to a private, patient-centered model,” as the Alliance’s website puts it.

The authors of the Affordable Care Act weren’t keen to make an exception for these ministries, but they knew that if they didn’t, they would be putting the bill at risk. “It would have been none of our choices,” said John McDonough, a professor of the practice of public health at Harvard and former adviser to Sen. Ted Kennedy, who worked on the development of the ACA. “But with all the disruption and opposition to the legislation, we were also concerned about the public response and impact on wavering Democratic senators if this became a public controversy, which seemed more than possible.” So the ministries were written into the ACA, with their members exempt from having to pay the tax penalties associated with the individual mandate.

Aware of their unique position in the health care landscape, these ministries continue to think about how to protect themselves from meddling regulations, and that involves a robust public relations effort. Deborah Hamilton, who heads Hamilton Strategies, the public relations firm that represents Samaritan Ministries, declined to arrange an interview after asking me via email whether this would be a “positive” article, and then told me that she did not think BuzzFeed News would be a “strategic media outlet” for Samaritan.

I did speak with Jon Watts, a former member services advocate at Samaritan Ministries who is now a student pastor at Crosspoint Community Church in Eureka, Illinois. He loved his time working for Samaritan, which he describes as “a phenomenal place to work” with people who came from “a wide variety of evangelical backgrounds.” For Watts, Samaritan was “a place to be challenged to grow in your faith around other people who are also pursuing Jesus with you,” where he could talk about theology on his lunch break. Watts would occasionally mediate difficult situations, like instructing a member about what to do if a check bounced or what to do if someone was late in sending in a share (usually, wait on another member’s check to come in).

What the AHCA would mean for sharing ministries remains uncertain — and it might not be good.

With the ongoing GOP effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, these ministries are once again concerned for their futures. In March, before the Republican American Health Care Act passed the House, Liberty HealthShare encouraged members to contact their representatives and ask for protections for health care sharing ministries: “[W]e are asking for the continued freedom to make health care decisions based on our needs and values,” part of the provided script read. Sharing ministries might seem like an appealingly stable alternative to traditional insurance coverage, as legislation is up in the air, but what the AHCA or other changes to health care policy would mean for them remains uncertain — and it might not be good.

“The American Health Care Act basically eliminates the individual mandate, the very requirement that likely made it much easier for health sharing ministries to pitch their cheaper but skimpier and discriminatory plans to consumers,” Lucia, the Georgetown professor, said. The membership growth that these ministries have seen in recent years could be stalled if the Republican health plan goes forward, according to Lucia, “because under the AHCA consumers won't have to be covered at all, and the market will likely be flooded with plans that are similar to those being marketed by health care sharing ministries.”

There’s some irony in all of this. Most social conservatives and many Christian organizations are united against the Affordable Care Act: Richard Land, while president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, said that Obamacare was written by “ideologues” who represent “the greatest threat to religious freedom in America.” But the ACA has allowed Christian health care sharing ministries to flourish, and it could be that the Trump-backed AHCA is the thing that will cause them to falter.

Still, ministry leaders have confidence in their continued survival. Samaritan Ministries spokesman Anthony Hopp said in a recent interview with Christianity Today, “Health care sharing ministries existed before the ACA, God willing, they thrived during the ACA, and they will survive after.”

As nonprofits, these ministries aren’t holding on to vast reserves of cash, meaning they have less financial and political clout to throw around compared to big insurance companies — and leaving much less cushion between members and the ministry’s bottom line, should anything go wrong. Which does happen.

Some ministries have had solvency issues because of clear-cut financial mismanagement. Christian Brotherhood Newsletter, a health care sharing ministry based in Ohio, found itself at the center of a scandal in 2001 when its founder Bruce Hawthorn was found to have stolen over $700,000 from CBN’s coffers to pay for cars, real estate, an airplane, and the credit card payments of an exotic dancer. Members sued, saying that Hawthorn’s alleged theft resulted in payment delays of up to 18 months and millions of dollars — as much as $34 million — in unpaid needs. Hawthorn and others were eventually required to repay $15 million in money taken from the funds where members had sent in their payments.

Scandals like this are rare, but some state regulators consider the basic premise of health care sharing ministries misleading, and have tried (and mostly failed) to exercise oversight. In 2007, the state of Oklahoma issued a cease-and-desist order against Medi-Share, claiming that it was indistinguishable from traditional insurance: “If it looks like a rose and smells like a rose, then it’s a rose,” said Kim Holland, then Oklahoma’s insurance commissioner. The state passed a bill in 2008 that allowed Medi-Share to resume operations, but a number of Medi-Share members faced trouble nonetheless.

Karen Niles, a homemaker from Blackwell, Oklahoma, saw her brain tumor return during this period of time and was told by Medi-Share that it wouldn’t be able to share in any of her expenses. (The ministry had previously shared about $450,000 worth of needs related to Niles’ condition.) Niles and her husband, Robert, claimed that Medi-Share couldn’t pay because it didn’t have enough money; Medi-Share maintained that it couldn’t share her expenses because the ministry was told it couldn’t operate in Oklahoma. The Oklahoma Insurance Department said there was nothing stopping Medi-Share from facilitating payments in the state. The Nileses and Medi-Share underwent a binding arbitration process, which ruled in favor of Medi-Share. Karen Niles died in 2011.

Every state in the US has a department that regulates insurance, but state policies on health care sharing ministries vary widely, if they exist at all. Insurance commissioners in Washington and Kentucky, as well as in Oklahoma, have all tried at different times to stop certain ministries from operating within their state borders, on the grounds that they are actually insurance companies and should be regulated as such. But in each case, the ministries were given exemptions by state legislatures that saw the issue as one of religious freedom.

In recent years, health care sharing ministries have worked with the conservative legislative forum the American Legislative Exchange Council to prevent the same back-and-forth from playing out in other states. ALEC offers legislators a model exemption bill that argues that “the regulatory requirements of insurance, if imposed on HCSMs, would destroy the voluntary, ministerial nature of the organizations.” As of the last amendment, in 2011, 11 states had safe-harbor exemptions for health care sharing ministries. As of last year, 30 do.

At the heart of the debate is the question of how health care sharing ministries differ from traditional insurance, and, ultimately, what the consequences of those differences are. Health care sharing ministries are legally required to disclose the fact that they are not insurance. Which is fine, but to hear them tell it, theirs is still the superior product. In its prospective members packet, Samaritan Ministries includes a glowing letter of recommendation from one couple: “We became aware of Samaritan Ministries in 2001 or 2002, but continued to play the juggling game with the insurance industry due to our lack of faith/trust in God’s provision through Samaritan.”

The letter goes on: “I would recommend this over EVERY ‘insurance’ product out there. Traditional ‘insurance’ has no assurances. In fact, everything is written in such a way that there is no assurance at the bottom line. We just wish that we had trusted in His provisions sooner.”

Just a few pages later in the membership application, though, is this proviso:

Samaritan Ministries and its members assume no responsibility for your medical bills. Whether you receive any share money to help you with your medical needs will depend on the voluntary giving of your fellow members as an expression of Christian love, but no matter how much money you receive, you always remain solely responsible for payment of your own medical bills.

The Affordable Care Act was written in part to ban certain discriminatory practices that led to people being denied insurance coverage. But health care sharing ministries have retained the right to discriminate, either by not sharing certain costs or by requiring more of certain members they deem unfit. For example, health care sharing ministries uniformly refuse to share costs related to self-inflicted injuries or suicide attempts — an issue that has also plagued traditional insurance companies, despite a health care privacy law requiring them to do so. Nor will they share needs related to fertility treatments, contraception, or, in some cases, injuries related to acts of war.

Several ministry plans have special tracks for overweight members, requiring them to meet regularly with coaches, as with Medi-Share’s Health Partner program: “If a Member experiences significant weight gain, he or she will be required to participate as a Health Partner.” The Medi-Share guidelines for Health Partners adds that “by reversing and/or preventing certain diseases, people are able to live healthier and fuller lives, ultimately being able to do more work for the Kingdom of God.”

Even if health care sharing ministries are very good for (most of) their members, ultimately they make it more difficult for traditional insurance plans under the ACA to flourish. “When you have a system like the ACA marketplace that covers everyone with robust coverage, regardless of their gender, age, or health status, what you don't want is any seepage from that pool of risk,” said Lucia, the professor. “When healthy people leave the marketplace for cheap and skimpy coverage, it drives up premiums for everyone left behind.” (The current AHCA bill, which would allow healthy people to leave their community pools of coverage for less expensive plans, would essentially write a version of that seepage into law.)

They may divert resources from the most vulnerable, and undermine the common good for the well-being of the devout few.

Most ministries have lifetime caps on the amount of money they’ll share per illness. For example, at Christian Healthcare Ministries, there is a $125,000 lifetime limit per diagnosis. (If you enroll in the Brother’s Keeper “catastrophic bills program,” you can pay more into the program each quarter and share costs over that amount, although there is no guarantee that all your costs will be shared.) A cancer diagnosis or complications with the delivery of a child can result in bills well over that standard lifetime limit, leaving members on the hook and in search of an insurance program that will help them out. And since insurance companies can no longer discriminate against sick people, they must accept whatever patients come back to them from these ministries — now with more serious and more expensive conditions.

This question of seepage is also, in a way, a question about the fundamental nature of health care sharing ministries. These ministries want Christians to “bear one another’s burdens,” but in practice they may divert resources from the most vulnerable, and undermine the common good for the well-being of the devout few.

Insurance is far from perfect — unwieldy, expensive, and often byzantine in its structure. Disputes are common and there is no guarantee of fairness. Yet the contract involved with insurance exists to protect consumers. In signing up for health care sharing ministries, those consumers are legally agreeing to be financially responsible for all of their own medical bills, while hoping that their community of Christians won’t leave them in a desperate situation. A popular saying in evangelical churches is that everyone — even atheists — has faith. It’s what we put our faith in that differs.

Insurance companies deal in a strange collision of the ethics of capitalism, compassion, and cronyism, in a manner that often makes it difficult for the sickest people to get the money they need for care. Customers who take out more money than they put in — to pay for surgery, chemo, radiation, or hospice care, perhaps — are a drain on their system. So as insurance companies allocate resources, they are also making statements about which patients, and which conditions, are worth coverage, and which aren’t — in effect enacting a system of values.

Health care sharing ministries also enact values, and they exist in large part because one or two Christian individuals were moved to put their faith into action in new ways. Most ministries cite the same Bible verses as foundational to their existence: Acts 2 and Galatians 6. Acts 2 describes the life of the early church, just after Jesus’s death and resurrection: “All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need.” And in Galatians, the Apostle Paul encouraged Christians to “carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ.”

Jesus, after all, never asked about pre-existing conditions.

The Christian faith has a long history of caring for the health of the most vulnerable, following Jesus’s example of healing many of the outcasts of his day — the blind, the lame, lepers — as well as children. For some, like the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, the mandate to care for “the least of these” meant they offered health care for orphaned children in New York during crises of public health. The Catholic Church is currently one of the largest, if not the largest, private providers of health care in the US, with nearly 650 hospitals across the country. But truly universal health care is often lost in translation, with each sect offering care to those it deems worthy due to practical considerations, and by its own subjective standards. Are we holding sharing ministries to the standards of a Christian organization, or are we holding them to the standards of other health insurers? And when they incorporate parts of both, how should this new space be regulated? What does it mean to be a “Christian” organization, anyway?

Faddis, the Solidarity HealthShare cofounder, told me that some Catholic bishops encouraged him to expand Solidarity’s sharing into mental health treatment, which it will begin to do this year, offering to share up to seven therapy sessions. “We’re all trying to be as generous as we can,” Faddis said of his sharing ministry colleagues. “We want to say, ‘Bring everyone.’ But in being practical and good stewards, we have to consider” financial limits.

Radical inclusivity is a noble and biblical ideal for Christian organizations to work toward. But, as Molly Worthen pointed out in her 2015 New York Times op-ed about health sharing ministries, they don’t resemble Jesus’s healing ministry so much as they do the mutual aid societies that flourished during (and since) the Gilded Age. Jesus, after all, never asked about pre-existing conditions.

No organization that claims to be Christian can ever fulfill everyone’s idea of what that should look like. If the conversations I’ve had over the last four months are any indication, sharing ministries’ constituents are generally very pleased with the care they receive. That may be enough. However, there are Christian values that can seem at odds with one another. When they collide, the results can be messy, denying care for people who have violated some tenet of Christianity — real or perceived.

All five of the big ministries require their members to sign a statement of faith; some, like Samaritan and Medi-Share, require that members agree to reserve sex for lifelong marriage between a man and a woman. They won’t share treatment costs for STDs unless it can be proven that they were acquired “innocently,” i.e., through a blood transfusion or sex within marriage.

These prohibitions may lead young adults to commit one sin (lying) to cover up another, just to stay on their parents’ plan. That was the case for Sarah (not her real name), a pastor’s daughter in a small town in Kansas. Sarah, who just graduated from high school and will head to college in the fall, got a letter from Medi-Share around the time of her 18th birthday that asked her to agree to the ministry’s “lifestyle agreement” in order to remain included in her parents’ plan.

“I’m grateful to have Medi-Share, but I want birth control so I don’t end up a teen mom.”

One of the three primary “biblical standards” Medi-Share requires for eligibility is “No sex outside of traditional Christian marriage” — but Sarah has been having sex with her boyfriend for the last few months. Sarah didn’t feel like she could talk to her mother about it, so her older sister took her to get birth control — an implant in her arm — in another city. “I’m still a Christian,” Sarah said. “I’m grateful to have Medi-Share, but I want birth control so I don’t end up a teen mom.”

If she did, she and her boyfriend would be on their own; many evangelical sharing ministries, including Medi-Share, won’t share in maternity costs for unwed mothers. (Solidarity and Liberty HealthShares both share costs for unwed mothers.)

“There are times even in the Christian community that unwed women become pregnant,” read the Christian Healthcare Ministries guidelines. “Christian Healthcare Ministries members have agreed not to share medical bills for pregnancies of unwed mothers. Instead, Christian Healthcare Ministries recognizes that in such circumstances the assistance needed goes far beyond financial aid. Therefore, we encourage you to seek help from a compassionate, Christian pregnancy center if you find yourself in this situation…You are in our prayers.”

Medi-Share has the same policy, with the stated exception that it will publish costs related to such a pregnancy if it is the result of a rape, but only if the rape is “reported to a law enforcement authority.” There are, of course, many reasons women choose not to report rape to law enforcement, including that they often feel revictimized in the process. But the choice not to do so would mean that they would have to shoulder the entire cost of their prenatal care and delivery, which in most hospitals generally runs into tens of thousands of dollars.

I asked a representative of Christian Healthcare Ministries how they would respond to a difficult situation in which, say, a member was raped and needed assistance with maternity expenses. “For things outside the control of our members, we will look at it individually and with an attitude of mercy,” said Lauren Gajdek, Christian Healthcare Ministries' communications director. “CHM would support someone who was raped and pregnant. We are a ministry. The criminal would be held accountable to the extent of the law and CHM would coordinate with the family and all applicable resources to assist the victim.”

But the messiness of any system that determines worthiness on a case-by-case basis becomes apparent fairly quickly, and makes for some strange rules for women in vulnerable positions. Samaritan Ministries refuses to share costs related to ectopic pregnancies, which occur when the fertilized egg attaches itself somewhere outside of the uterus, usually in the fallopian tubes. Ectopic pregnancies can almost never go full term, and women who have them often require emergency surgery to remove the embryo in order to save their own lives, which can cost upwards of $15,000. Yet in its guidelines, Samaritan Ministries clarifies that “considerations of the health or life of the mother does not change that the removal of a living unborn child from the mother may be a termination of life.”

While I spoke with the Olsons in their kitchen in Illinois, Tess was upstairs playing with her brother. But she knew our time was almost up, and I had promised to play a game with her before I left. She ran into the living room and, having a hard time deciding on a game, made up her mind to dance instead. Her mom played a clean version of “Uptown Funk” (Sample lyric: “Fill my cup, put some water in it”) as Tess did the splits, jumped, and shook her hips.

Even though Samaritan wouldn’t cover the medical tests Zain and Tess needed when they were adopted, everything turned out okay for the Olson family. Erik had just started a new job when they brought Tess home, as vice president of Dignity Coconuts, a community formation organization that works primarily in the Philippines. Through Dignity, the Olsons were all able to get health care coverage, including coverage for a regular medication that Tess takes. They are a healthy, energetic family of four, with homework to do and errands to run and hockey games to go to.

As long as potential changes to US health care policy — and the fate of the health insurance laws and marketplaces we do have — remain unsettled, the only thing that’s clear is that no one’s future is certain. Christian health care sharing ministries will continue to lobby for their special position, and consumers will continue to look for the best way to save money while taking care of their families. Faith, in every sense of the word, will be required for everyone involved — faith that the government will keep loopholes open; faith that fellow Christians will send their checks every month; faith that God will provide. And the Olsons, despite leaving Samaritan, still have faith.

“Erik and I both have a heart to say we really believe in what Samaritan does, and think there are a lot of good things," Bet said. "I just want them to rethink and really think about why they're doing it that way.” ●

Laura Turner is a writer in San Francisco.