Immigration is a thorny issue for the government right now, particularly after Britain's vote in June to leave the EU – which came after a strongly anti-immigrant Leave campaign – brought the Conservative party’s 2015 manifesto pledge to control immigration to the top of the agenda.

A tug-of-war over freedom of movement is now beginning to emerge between the government's Brexit team and other European leaders. Meanwhile, at home, schools have started collecting data on where children were born – in some schools, only the parents of non-British children have been asked to declare this information.

The Department for Education has said it won't pass children's country-of-birth information to the Home Office, and instead will use it to help understand how to best further children's learning. But the Home Office has used school data for immigration investigations before, and leaked documents show the government has previously tried (and failed) to pass plans that would limit school places for children of illegal immigrants.

So what is actually going on with schools and immigration right now?

Is it any different for a non-British child trying to get into a UK school?

Under current British law all children under the age of 16 who are living in the UK are entitled to a school place.

This includes children who were born outside of the UK, even if their parents are undocumented or illegal immigrants, as well as refugees whose application for asylum is pending approval.

Individual schools and local councils can set their own specific admissions processes, which may give priority to children who have other siblings at the school, children who practice a particular religion (in the case of faith schools), or simply children who live in close proximity to a particular school. In selective areas, an entrance exam will determine where they'll be granted a school place.

"The Office of the Schools Adjudicator is in place to make sure schools’ admissions criteria are fair," a Department for Education spokesperson told BuzzFeed News.

"Crucially immigration status/ethnic background/nationality are NOT among those criteria."

What do schools have to do with immigration then?

It's no secret the current government hopes to reduce the number of people from other countries coming to live in the UK, and there are growing concerns that public services such as schools and hospitals might be used by the government to track and potentially deport illegal immigrants.

The Department of Health said it would consider making hospitals check patients' passports to determine whether or not they should pay for treatment – a move Theresa May has already supported on maternity wards.

An investigation by the BBC revealed that Home Office plans in summer 2015 to "deprioritise" the children of illegal immigrants when allocating school places were only dropped when then education secretary Nicky Morgan expressed "strong concerns" over "practical and presentational issues of applying our strong position on illegal migrants to the emotive issue of children's education". Given that the home secretary at the time is now PM, this suggests the government wouldn't rule out less prominent ways of achieving the same result.

The leak follows the recent addition of children's country-of-birth and nationality data to the information collected in the schools census and added to the National Pupil Database.

"We can see a pattern," Laura McInerney, editor of Schools Week, which has covered issues around education and immigration extensively, told BuzzFeed News. "In 2013 there was consideration on banning the children of illegal immigrants from schools, but that broke UN rules.

"We now see there was a move by the Home Office to perhaps deprioritise immigrant children.

"While it looks like the DfE has now held off on that, when the same team who were in the Home Office then are now in charge of the country, it is fair to think that perhaps this policy would come back around again, and it might be something that schools are encouraged to do."

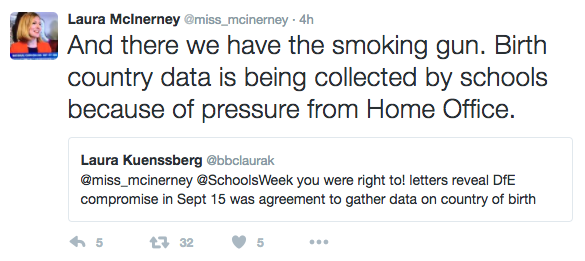

According to BBC political editor Laura Kuenssberg, leaked letters show the plans to collect children's country-of-birth and nationality data were introduced as a compromise for dropping May's more extreme "deprioritisation" plans.

Gracie Mae Bradley, co-founder of campaign group Against Borders for Children, also believed the new data collection was particularly concerning in the context of previously thwarted plans following May's move from the Home Office to Number 10.

“It’s sad but not surprising that proposals to treat migrant children this way were mooted as recently as last year," Bradley told BuzzFeed News. "Even if they are shelved for the moment, yesterday’s home secretary is today’s prime minister, and the government is currently pressing ahead with plans to draw up foreign children lists through schools.”

Schools must be safe spaces for ALL children. They are NOT border enforcement, nor must they ever be #BoycottSchoolCensus

Following the BBC leak, Labour shadow education secretary Angela Rayner expressed concern that bringing issues around immigration into schools could lead to segregation and breed extremism.

"We have a legal and moral obligation to educate these children," Rayner said. "It is shocking that as home secretary, Theresa May was prepared to behave in this way.

“Children should not be used as pawns in Tory political games and schools should be protected as places of learning – not a replacement border force."

Why would the Department for Education want country-of-birth data if it's not using it to monitor immigration?

The department said it is collecting the data to "better understand how children with, for example, English as an additional language perform in terms of their broader education and to assess and monitor the scale and impact immigration may be having on the schools sector".

But several parents have pointed out that just because a child was born in another country does not mean English is their second language.

Melissa Lazzaro, whose French-born daughter is growing up in England and therefore speaks English as her first language, told BuzzFeed News she found the justification "dodgy".

“I’d understand if the question was, ‘What is the child’s first language?’ – that would make sense,” she said. “Asking about their country of birth doesn’t make any sense to me.”

How exactly the government plans to use the data to "monitor the scale and impact immigration may be having on the schools sector" is unclear, and the Department for Education has so far refused to disclose the agreement it has with the Home Office over sharing the data.

@twrc yep. Here's the letter that preceded it.

"Unfortunately, all the evidence points to this being an immigration tactic rather than having anything to do with trying to improve the education of young people or supporting our schools," Liberal Democrat Lords spokesperson for home affairs Lord Paddick said during a recent House of Lords motion of regret over the new data collection.

During the same debate, Lib Dem peer Lord Storey said: "Against a backdrop of a massive increase in anti-immigration rhetoric, as witnessed by big increases in hate crime, and at one stage the government considering asking firms to report on the number of foreign staff they employed, there is real concern among members of different ethnic groups about victimisation and being targeted."

Jess Edwards, a primary school teacher in Lambeth, London, told BuzzFeed News she believed it has been the government's intention to monitor immigration via schools for a couple of years. "We’ve always said that there was a move towards making schools part of the UK border force," she said.

Edwards said the BBC leaks proved teachers were right to be suspicious of the collection of country-of-birth data.

"[May's] gone for the softer option, with the intention, we believe, of beefing that up," she said. "Schools should be a safe place for children, and if parents are fearful of what will happen if they enrol their children in school, or if they hand over info to schools, education overall will suffer."

Sir Michael Wilshaw, the chief inspector of English schools, has also expressed disdain over country-of-birth and nationality data being collected. "Schools shouldn't be used for border control," he told Schools Week. “I wouldn’t want anyone, least of all headteachers, to break the law. But I think this is a daft idea."

Should parents be worried?

"I don’t think that means parents suddenly need to worry about schools holding data on their child, and I wouldn’t encourage parents to get upset, suspicious, or jump to any conclusions," McInerney told BuzzFeed News. "I think at the moment we can say that the data is being used sensibly and there won’t be further checks."

But, she said, it continued to be important to hold the government to account on their use of children's data. "I think it’s right for the media and people in policy to ask questions to get absolute clear assurance that this policy of banning or deprioritising children of illegal immigrants is not the plan going forward."

Some parents, however, have felt unsettled by the BBC's revelations that the Department for Education considered putting immigrant children to the back of the queue for schools.

"I think this leaked info is precisely the sort of thing immigrant parents feared when asked to produce info on nationality," Catherine Aman, an American mother living in Cambridge, told BuzzFeed News.

In October Aman provided information to her daughter's school confirming that the child had been born in the US.

"Suggesting that schools should function as part of the immigration system is a bad idea, obviously," she said. "My daughter and I are here legally, but it's disturbing to think that the prime minister proposed this (albeit in an earlier role)."

When plans to collect country-of-birth data were originally announced, users on parenting network Mumsnet appeared to give the government the benefit of the doubt over how it intended to use it. But following the BBC's revelations yesterday, the temperature had changed somewhat.

"Apparently the government are in fact, actually, a fucking disgrace," one user wrote. "I'm appalled. And to those I disagreed with: I'm sorry, you were right. And I'm sorry you were right."

Another called the measures "ethnic registration by stealth", adding: "Bastards."

As a teacher, Edwards said, she was not comfortable with asking parents to provide country-of-birth data for their children while at the same time encouraging children to celebrate diversity and difference.

She told us that at her school in multicultural south London they hold a refugee week where children learn about asylum-seekers, and teach lessons on black history and where people are from in the world all year round.

"We’re saying to children that you should celebrate where you’re from and celebrate who you are, and now we’re adding a layer of insecurity into that by making children fearful of disclosing information," she said.

Another schools census is due to take place in January 2017, and campaigners are keen to have the country-of-birth and nationality questions dropped from it.

"It’s deeply worrying, at a time when the government wants all our personal data opened up in new data-sharing legislation, to find the facts on the school census data used by the Home Office only being dragged into the daylight through [freedom of information requests], and secret policy plans only through leaks," Jen Persson of campaign group Defend Digital Me told BuzzFeed News. "It all now requires the utmost transparency, oversight, and safeguards."

So - two separate questions: why does the DfE need the data, and why won't it release its pledge not to share it with the Home Office?

She continued: "Parents must be able to trust what their data are used for and the best interests of the child must be a primary consideration in all legislation and policymaking.

"Every child under 16 has an equal right to education, just as every child has an equal right to confidentiality."

In the meantime, McInerney noted: "It’s worth reiterating that parents are not required to provide this information. So although schools are being asked to get it, parents are not required to provide it, and schools are not required to fill the boxes in, they’re just required to ask."

Parents who provided country-of-birth and nationality data during the October schools census are now also entitled to ask for the government to delete the information if they no longer wish for it to be held.