Victorian premier Daniel Andrews has issued an apology to people convicted of historical homosexual sex offences, the first of its kind offered in Australia.

Speaking to the Victorian parliament on Tuesday, premier Daniel Andrews apologised to people convicted of historical homosexual sex offences no longer considered crimes. Up until 1981, gay men were convicted of offences such as buggery, loitering for homosexual purposes, gross indecency, and offensive behaviour.

"There was a time in our history when we turned thousands of ordinary young men into criminals. It was profoundly and unimaginably wrong," Andrews told the parliament.

The premier said in no uncertain terms that the government had to take responsibility for the laws it had enacted in the past.

"It is the first responsibility of a government to keep people safe," he said. "But the government didn't keep LGBTI people safe.

"The government invalidated their humanity and cast them into a nightmare. And those who live today are the survivors of nothing less, nothing less than a campaign of destruction, led by the might of this state."

Andrews took the opportunity to send a message to all LGBTI Victorians, saying "you have a government and a parliament that is on your side".

He also said that he believes the apology is a world first.

"To our knowledge, no jurisdiction in the world has ever offered a full and formal apology for laws like these," he said.

Six men have so far successfully expunged their records under a Victorian scheme that began 1 September.

The people convicted under these laws – the vast majority gay men – have welcomed Andrews' gesture as a way of starting to put their trauma behind them.

In 1977, Tom Anderson, then 14, was sexually abused by a male employer. But after reporting the incident to police, he was charged with two counts of gross indecency and one count of buggery.

“After almost 40 years I am glad to be able to attempt to finally put to rest this event in my life," he said. "This event has caused me untold anguish, anxiety, stress, and trauma throughout my life and the formal state apology goes a long way to hopefully easing that in my future.

"It has been a long and at times very painful and traumatic campaign leading up to this apology and only time will tell the true effect and closure it will bring me."

Anna Brown, director of advocacy at the Human Rights Law Centre, said the apology would recognise the harm caused by these convictions and highlight that sex between consenting adults should never have been a crime.

"This apology is a powerful symbolic act that helps to repair the harm caused by these unjust laws and affirm the value of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people’s sexuality," she said.

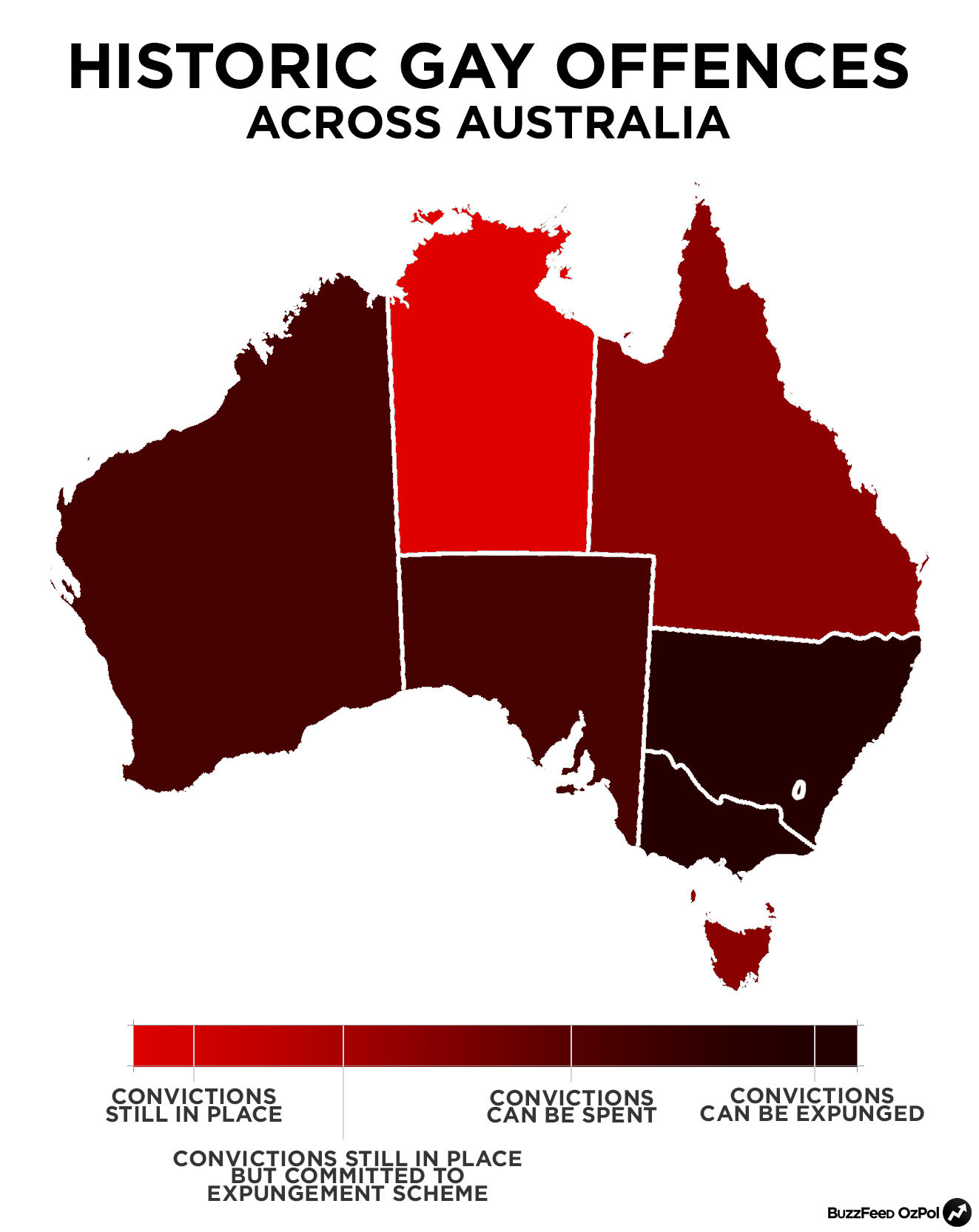

Australian states and territories vary in how they have dealt with people affected by wrongful convictions.

Victoria, NSW, and the ACT have all introduced schemes to expunge historical homosexual sex offences, while governments in Tasmania and Queensland have committed to such schemes but are yet to legislate them.

Tasmania has also committed to a formal state apology, similar to the one offered by Andrews today.

In South Australia, a 2013 amendment allowed people convicted of historical sex offences to apply to have their convictions “spent” – but not expunged. This is also the case in Western Australia, where it is illegal to discriminate against a person on the basis of a spent conviction.

The Northern Territory has not given any indication of introducing expungement legislation.

When a conviction is “expunged”, it is erased in the eyes of the law. The conviction no longer shows up on a police records check, people are not required to disclose it for any reason, and they cannot be denied a job because of it.

A conviction being “spent” is a slightly different process, which only allows the criminal record to be amended after a time period of not offending – in SA and WA, 10 years. There are also certain exemptions where a spent conviction must be disclosed, which is not the case for an expunged conviction.

Anna Brown told BuzzFeed News it is essential that states legislate to make it as though the convictions never took place at all.

"What should happen is that states should legislate so victims can apply to be restored to the position they were in before the conviction," she said.

"There are a number of accompanying measures: Being able to say on oath you were never convicted, having the records deleted, or at least annotated to say it's been expunged, [and] ensuring it's an offence for people to disclose information revealing the person's conviction."