Penny Wong is often mentioned, with varying degrees of seriousness, as an alternate prime minister.

Intelligent and unflappable, Wong is among Labor’s most savage performers on the floor of parliament. She's immensely popular among the Australian political left, and serves as an inspiration for thousands of women, migrants, and LGBT Australians.

Why then does her party not turn to her, to lead Labor back into government?

For Wong, sitting across from BuzzFeed News, coffee in hand, the answer is personal.

“When I was touted for preselection, how many people who were a, female, b, Asian and c, gay, were being pre-selected for a party of government?” she asks, counting the three things off on her fingers. (The answers: roughly 27%, none, and none.)

“It would have been inconceivable for me that I could have run for the house.”

But the simplest way of putting it is that she wouldn’t expose her family to the blinding, toxic elements of the national electorate.

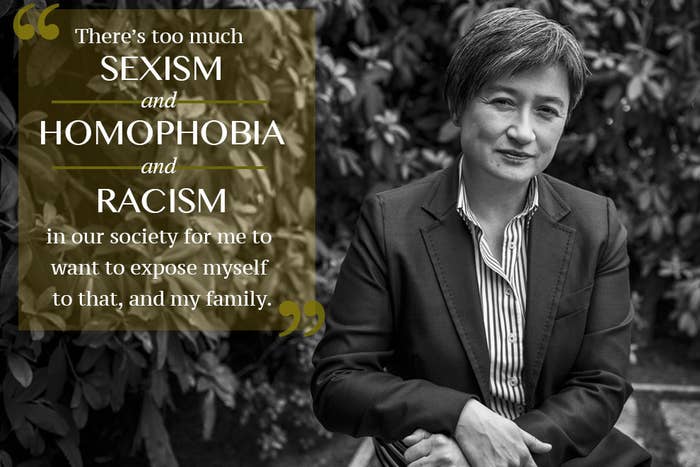

“There’s too much sexism and homophobia and racism in our society for me to want to expose myself to that, and my family.”

Wong is so together that it’s hard to imagine her ever being fazed by the undercurrents of bigotry running through Australia – even though, unlike the rest of the parliament, she’s under attack on three fronts. But she has a practical reason for eschewing the top job too: she just adores tricky legislative work.

“I used to be more of a nerd than I am. Not a computer nerd, just sort of nerdy. I like the notion that the Senate is actually where you legislate, where you look at stuff,” Wong explains.

“I always wanted to be a Senator,” she says, and then quips: “I’m not very ambitious.”

Of course, this is ridiculous. Currently, Wong is the most senior member of the opposition in the senate. She was the first Asian-born member of the Australian cabinet, the second gay MP to ever enter the Australian parliament, and the first lesbian. That means she was a sitting member in 2004 when the Australian parliament amended the Marriage Act to explicitly exclude same-sex couples.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence then that Wong’s journey to the top echelons of the parliamentary Labor party has run parallel to the Australian public’s journey to accepting marriage equality. For Wong, that journey has been long and at times painful. For seven years between 2004 and 2011, Wong stuck to the party line on marriage. And recently, as the marriage equality debate has been increasingly heated, she’s come under fire for it.

In a particularly memorable moment on the ABC’s Q&A program in 2010, Wong uncomfortably laid out her reasons for supporting traditional marriage – but her reluctance was clear.

Does she regret it? The short answer is no.

“I’m very relieved I no longer have to put that position because we changed the party’s position,” she says, her relief palpable. The way Wong sees it, the most ethical way to navigate the marriage quandary was to argue for same-sex marriage inside the party, and stick to the line outside of it.

“I guess… look. People make decisions about how they’re going to express their politics,” she says. “Some people do it as community activists, some people do it as writers or commentators, other people do it by joining particular parties.”

Obviously, Wong does it through the Labor party. And the upside, she says, is that she can enact real change.

“As a party of government, that gives us the opportunity to implement reforms in government, which is really how you change people’s lives,” she says.

And the downside is what happened to Wong on Q&A.

“Just as you get the benefits of collective decision making when they reflect your personal views, you also have to accept, at times, collective decision making that doesn’t reflect your personal views.”

The 2011 decision, when Labor finally swung around to reflect the views of Wong and others on marriage, happened after grassroots members, Rainbow Labor and external influences pushed for change, Wong says.

“[It] was a very important moment for us all.”

But even after the policy changed, Labor failed to legislate for marriage reform while in government, thwarted by a number of Labor MPs who opposed the reform on the basis of conscience and a conservative opposition united against marriage equality.

The parliamentary Labor party’s decade-long intransigence on the issue contrasted with Wong’s personal popularity with the grassroots of the party has never been on greater display than at Labor's national conference in July this year, when a push to end the party's conscience vote on marriage equality went south.

In the dying throes of the conference, a compromise was struck between the party’s left and right factions. If Labor wins the next election, the deal went, a bill for reform would be introduced within 100 days. In return, the conscience vote stays for another political term, until at least 2019.

Labor leader Bill Shorten announced the compromise with a spun positivity that gave the impression of a party-wide love in, even as criticism rained down from unhappy campers on both sides of the debate.

But then Wong made her way to the stage, putting a temporary halt to the argy bargy. As she walked, her party rose around her and started a round of applause that continued long after she had made it to the lectern. The standing ovation momentarily brought her to tears.

Wong with Anthony Albanese, Bill Shorten, Tanya Plibersek and Louise Pratt at the Labor conference in July.

“To be completely honest with you, I just wasn’t expecting it,” she says.

Wong had spent much of the afternoon conducting a “lengthy and emotional discussion” with members of Rainbow Labor, the grassroots LGBTI group, many of whom were upset by the compromise.

“We had the whole gamut of views and emotions, it was an emotional discussion for many of them,” Wong says. “There were people in there who were quite rightly saying ‘You have to understand what a conscience vote says to us, it says we’re not equal in our own party’. Which is fair enough.”

It had been a long day of negotiations on a variety of other things as well. Wong was tired. And the standing ovation just came out of nowhere.

“This might sound goofy... I just didn’t anticipate the standing ovation,” she says. “If you see [the video], I don’t actually know what to do.”

Wong laughs. “I was like… do I interrupt them? I sort of couldn’t understand why it was happening. I was a bit overwhelmed, I think.”

It was a rare show of raw emotion from the cool, calm Wong – an epic diversion from the face she puts on in question time, and the sass she hurls at Coalition frontbenchers on Twitter. But the unexpected applause just struck home.

She tries to play it down, explaining the moment away as a show of support for the issue itself. “I was just the person at the time,” she says. But for observers, it was clear that the applause for Wong was just as much an acknowledgement of what she has endured in this debate as a sign of support for reform.

“For someone like me who’s been involved in trying to move the party forward on this, to see that was incredibly moving,” Wong says slowly. “It was a very beautiful thing.”

Amid the symbolism of a party standing to applaud, it is easy to forget that Labor only came around to supporting marriage equality relatively recently. Since then, the debate has only become more vitriolic, as countries around the world have redefined marriage to include same-sex couples while Australia stands firm. Amidst constant reminders to “respect all views” in the contentious debate, each side has only retreated further into their respective corners.

On the two main arguments currently tossed around – children, and religious freedom – neither side will give an inch. There’s no separating the personal and professional in a debate that cuts so close to home – so how does Wong do it?

“I don’t always,” she says quietly, her tone resolute.

“I think about young people all over this country, or older people who are still coming to terms with their sexuality, and how this debate lands in them. How they hear it. That’s one of the saddest things.”

Wong rifles through a folder on the table, looking for a copy of her speech from a 2012 vote that crashed out 98-42. “It’s very hard, isn’t it?” she says, flicking through sheets. “It’s very hard to not feel affected by it.”

Wong finds the speech, and reads aloud: “To young gay and lesbian Australians, to those who may not have come out yet or are finding their way. I want you to know that the prejudice you have heard in this debate does not reflect the direction in which this country is going.”

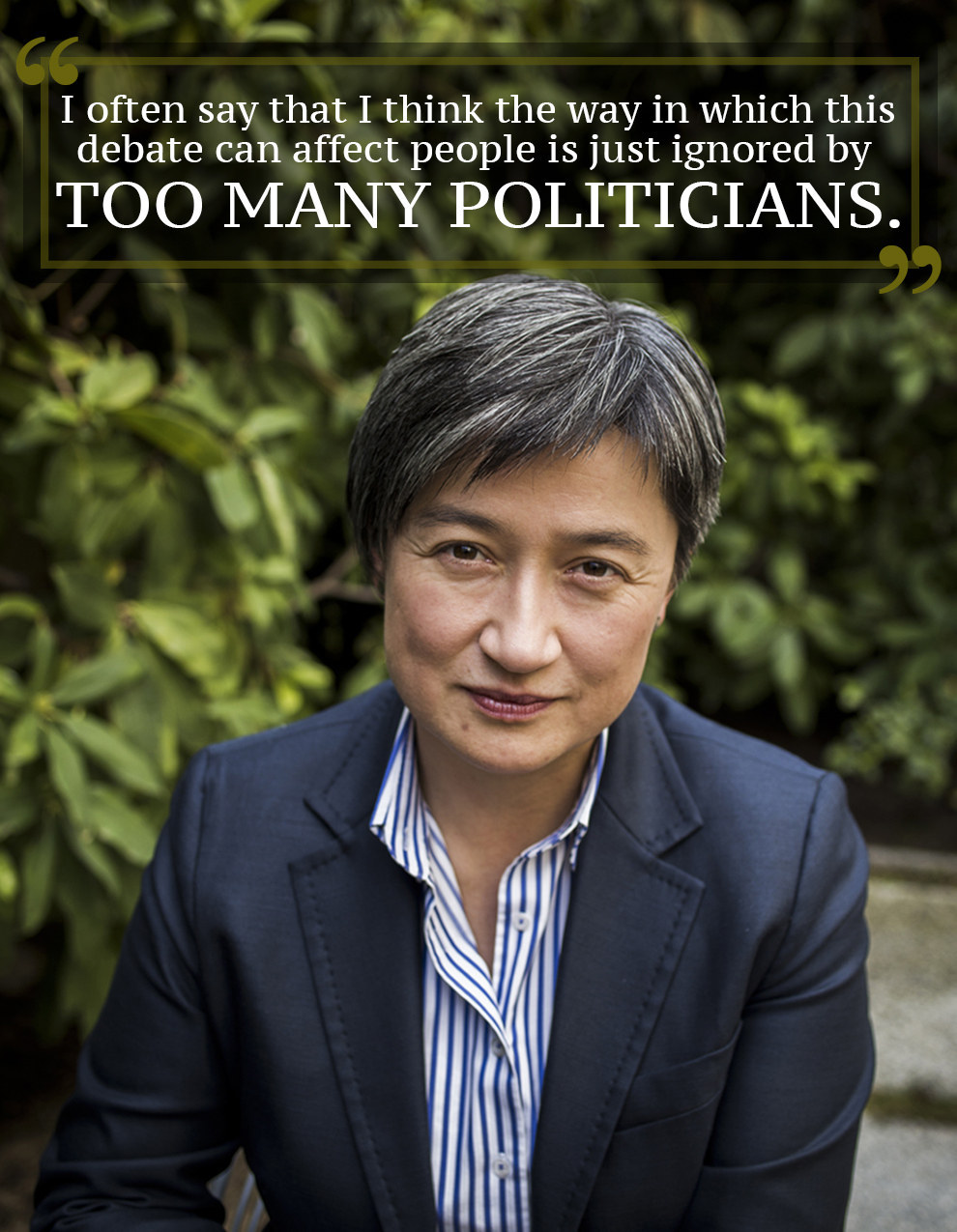

She puts it down. “I often say that I think the way in which this debate can affect people is just ignored by too many politicians,” she says.

“I have all of these years of political experience, all of this practice at political argument. I have a wonderful family, a rock-solid relationship, and I’m used to being in the public eye. And I still feel it. How is it for so many people?”

The answer – bloody hard – hangs in the air.

Despite recent comments about "hate speech" and "bullying" coming from those who support marriage equality, Wong is unconvinced that those against reform are bearing the brunt of the sometimes vicious debate.

“Let’s be really honest about who has been respectful and who hasn’t in this debate,” she says.

“Do the people arguing for equality ever diminish the relationships of heterosexuals? Do the people arguing for equality ever say that children of heterosexual couples are compromised? Do you ever get the sorts of emails and letters and tweets that have come out of this debate? Do people on the side of equality ever suggest that the other side is going to be advocating polyamory or bestiality?”

It’s clear she could go on, but she stops with this:

“If there’s respect, I wouldn’t mind a bit of respect coming our way.”

It's a glimpse into the sassy, no-bullshit way Wong is characterised online. On Facebook, comments praising Wong regularly amass enough 'likes' to rise to the top of news stories. There’s adoration on Twitter, too. But when you trawl through her mentions, ugly racism and homophobia rears its head.

When the idea is put forward that people love her online, Wong is quick to clarify that it’s not all praise.

“Some people do [love me]. Some people really hate me.” She pauses. “Some people really hate me.”

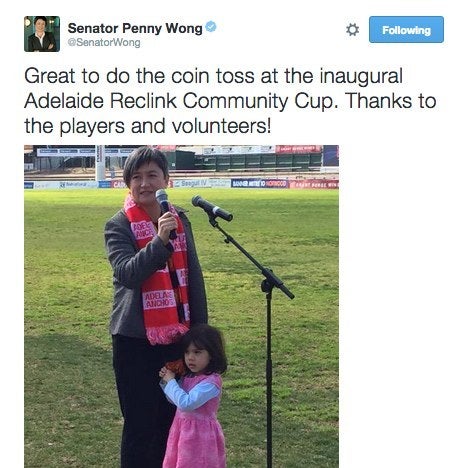

Like many politicians, Wong’s Twitter feed is a curious mixture of tones, with pictures of Wong at community gatherings dotted among digs at the Coalition frontbench.

After a vine of Wong snubbing Joe Hockey outside an ABC radio studio went viral, he had a go at her in question time. Wong responded with this:

The world’s most invisible Treasurer has gone on a rant in the House. Is it because I didn’t give you a hug last week @JoeHockey?

“I’m not as active online as some of my colleagues,” says Wong. “You’ve just got to be you... I just try to say what I think. And when I can’t, I don’t engage. I think most people don’t.”

“The Twittersphere is very good at working out fake,” she adds.

But on Facebook, more often than not, posts about Wong attract “Penny for PM” comments that inevitably pick up a swag of likes. Despite these informal public appeals, Wong's thoughts are clear on that particular avenue.

In fact, another reason she couldn’t be PM is because she dislikes being photographed – something that rapidly becomes apparent as she self-consciously submits to the photographer’s instructions in a small courtyard near her office.

When the photographer asks her to pose without her hands folded, she says that’s just how she does it.

“Hands in pockets?” he suggests.

“No, that’s too butch!” Wong protests.

It’s weird to hear an Australian senator drop lesbian slang like it’s no big deal. But then again, Wong isn’t your average senator.