When I got an email on the train home from work on Wednesday, informing me that the lead "no" group in Australia's same-sex marriage survey, the Coalition for Marriage, was launching an app, it immediately piqued my interest.

Coalition for Marriage is launching an app

Before you read any further, you should know two things about me: one, I love nothing more than developments in the Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey; and two, I have no life.

So naturally, when I got home, I cracked open a beer, downloaded the app, and started going through it (see points one and two).

The "Freedom Team" app, launched Wednesday, gamifies campaigning against same-sex marriage in Australia by offering points and badges for every door knocked, friend invited, and campaign update shared on the app. Players are ranked on a leaderboard depending on how many points they have.

It's made by Washington-based developer Political Social Media LLC, which also has listed an app for the Republican candidate in the race for governor of Virginia, Ed Gillespie; an anti-abortion app called Life Impact; and another simply called Right To Vape.

SPOTTED on the app leaderboard... #12 Wendy Francis #27 Peter Abetz #30 Bernard Gaynor (I'm #77)

Just surfing the app and reading through various articles took me up to 60 points (and a spot at #77 on the leaderboard). You can earn points by donating to the cause as well.

The app includes a FAQ page on how to respond to common questions, like "Why do you hate lesbian and gay people so much?" (The answer: "I don't hate anybody. I am concerned that changing the marriage law will have unintended consequences.")

But one aspect in particular caught the attention of, well, pretty much everyone who read the email sent out by Coalition for Marriage communications director Monica Doumit.

"The app will provide turn by turn directions to your nearest neighbour who is yet to hear from the campaign," Doumit wrote.

Off the back of a week-long furore over a text from the "yes" campaign, and a subsequent (but somewhat less intense) furore over robocalls from "no" supporting politician Cory Bernardi — an app that literally led people to another's door seemed to fall into the same category. Twitter was abuzz at the prospect:

"turn by turn directions to your nearest neighbour" - and the yes campaign is invasive???? https://t.co/6InCHLB7Gw

NO campaign have launched an app to help their side harass their neighbours... AND PEOPLE WERE WORRIED ABOUT A TEXT… https://t.co/XYwp7hZR2r

@lanesainty Uber but for harassing your neighbours

Umm this is fucking terrifying. @MarriageAll @LyleShelton weren’t you saying a TEXT MESSAGE was a violation of priv… https://t.co/u7Mdh2ehGc

Now, this really is intrusive. Who the hell wants their address controlled and being directed to by either side? https://t.co/v8BKyph6t3

@michaelkoziol They're tracking who comes to my house to convince me to vote no? This is beyond invasive! And creepy!

@lanesainty At least a person physically showing up on my doorstep, coupled with a robot phone call, will be less i… https://t.co/uw3G47jXUX

If someone from the "Freedom Team" comes to my door I shall be sure to invite them in and waste as much of their ti… https://t.co/UN1A16RRip

So I clicked the "Speak with your neighbours" option to find out more about these door-to-door directions.

After switching on location services, the app immediately offered up a list of addresses near me that had not yet been contacted by the "no" campaign — plus how many yards they are from my house. (I'm guessing it's the American app developers responsible for this particular shunning of the metric system.)

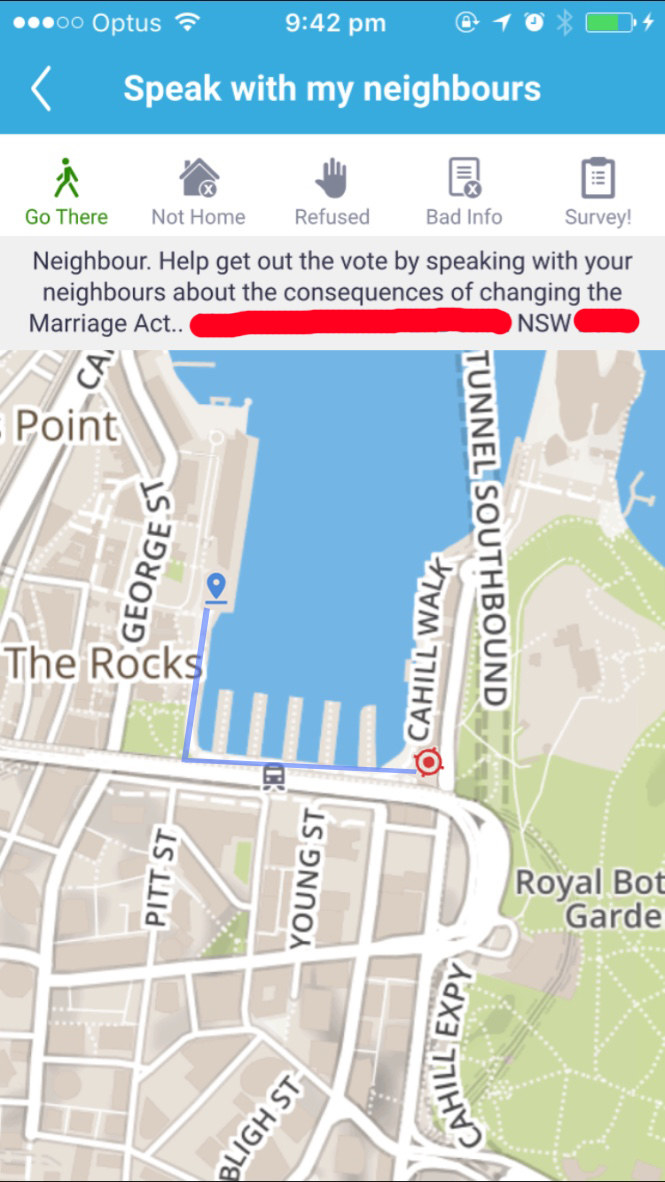

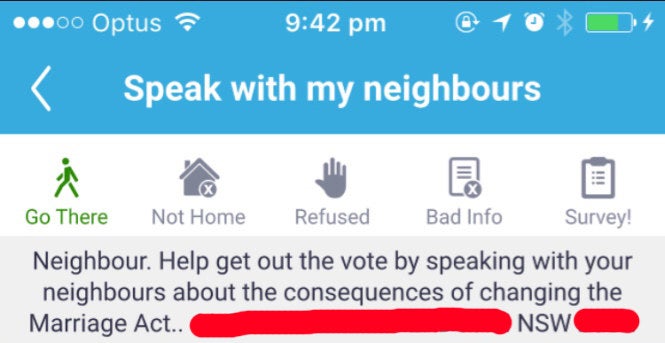

Once you tap on one of the addresses, you can then select a route to get there, via walking, cycling or driving. On the map, you are represented by a red dot and your destination by a blue marker. A blue line pops up letting you know where you need to go, just like in a regular maps app.

For obvious reasons I don't want to post a picture online of where I and the first neighbour I was visiting live, but here's a mock up of what it would look like if I was on one side of Circular Quay, Sydney, and the neighbour I wanted to visit lived on the other side.

So... after figuring all of that out, I suddenly thought: gee, I want to know what my neighbours think of all this. Do they agree that it's yet another intrusive campaigning method, or don't they care?

I looked at the first house on my list. It was a measly 204 yards away (I don't know how many metres that is but I understood it to be not many).

So I put down the beer (again, see points one and two), picked up my bag, grabbed a notebook, and followed the blue line around the corner and down the road to the first neighbour listed on my app.

Knock knock. I heard a fork clang on a plate and silently groaned: I've interrupted their dinner. Footsteps, and then an older woman opened the door and looked at me quizzically.

"Hi!" I said. "I'm sorry to bother you – I'm a journalist with BuzzFeed, and I'm working on a story about the marriage survey. I was wondering if I could ask you kind of a strange question about it."

She hesitated. "It'll only take a minute," I beseeched. "It's to do with an app that's led me to your door."

She kindly acquiesced, though said she didn't want to be named.

On the survey itself: "We don't care," she said.

"Love thy neighbour! It doesn't matter — gay, lesbian, who cares? Human beings. Love them. That's how it is. That's all I can say."

Then she said she had been married to her husband for over 50 years.

"It's all give and take," she said. "Sometimes you have to take more than you give."

I showed her the map, and she said it didn't worry her at all that I had been directed to her house via an app.

Then she said, again, that she and her husband are all about loving all humans: "We're right in amongst it. We've got them — lesbians, gay guys, they come here, we eat, share drinks. We love them."

The next house was further away, in a dark, quiet part of the next suburb, with a kid's bike chained to the metal fencing.

A woman there, in the middle of making dinner, didn't open the door but spoke to me through it instead.

"I'm not a citizen," she said, in a muffled voice, when I mentioned the marriage survey. "My husband can do the survey, but I can't."

I asked what she thought about the map app: "I don't know, I'll have to ask my husband."

At this point she still hadn't opened the door, and despite her stated ambivalence on the map app, I was definitely beginning to feel annoying — so I cut the 30-second conversation short and said goodnight.

After visiting each house, door knockers can enter what happened into the app using buttons at the top — not home, refused, and so on. (After each house I visited, I pressed a pop-up option to exit without recording a door knock, so as not to interfere with any campaigning efforts.)

I had forgotten my glasses and it was quite dark at this point, so I was having trouble seeing the house numbers from a distance as I wandered over to the next suburb. I finally found the next house on the list — number 69 — but no one was home. Alas!

At the next house, just down the street from there, an older man named John was watching TV at home, a cat perched in the window. Admittedly, he opened the door to my knock because he thought I was his next-door neighbour popping by for a chat, but he happily agreed to answer my questions.

John had voted "yes" in the survey already. I showed him the app, and the map that led me there.

"Why is my address on a 'no' campaign app, I wonder?" he asked. "How would they have gotten that?"

I explained that it wasn't that he was being targeted by the "no" campaign, but that the list was houses they hadn't doorknocked or contacted yet. Did it bother him? Not at all.

"I don't mind," he said. "I talk about [the survey] with my neighbours all the time."

"What do they say?" I asked.

"Certainly they're interested in getting a 'yes' vote."

I thanked John, and left him to his Wednesday evening TV.

The final house was large, two stories, and a little foreboding, with the door down a set of stairs and a wide balcony above. I knocked, and heard footsteps and a door open above my head.

"Hello?"

I looked up. A middle-aged man was peering down at me from the balcony.

"Hello sir! I'm a journalist with BuzzFeed and I'm working on a story about the marriage survey. I was wondering if I could ask you a kind of stra-"

He cut me off: "I'm not interested."

I tried one more time: "The reason I've come to your house is because one of the campaigns has put out an app that directed me here. What do you make of that?"

"I don't care which way or the other," he said, grumpily.

So with that, I called it a night, and went home to take part in another Australian tradition that's all about love: watching The Bachelorette.