It was late afternoon on December 19, 2016, when Lorena Bestrin went for a walk around the park near her house in the south-western Sydney suburb of Canley Vale.

She was thinking to herself, something has happened.

It was unlike her 25-year-old son, Amaru, to not be home by midday – at the latest – when he had been out the night before. He had only just returned from a stint in Chile, Bestrin’s home country, where she had hoped he would kick his heroin habit once and for all. Amaru had come back to Australia in high spirits, even hyped, and been exhilarated to see his mother and his 1-year-old brother before going out with friends.

“But everyone said, ‘He’s alright, you always worry about him’,” Bestrin told BuzzFeed News. It wasn’t the first time her adult son had not come home.

“I couldn’t think of anything,” she said. “I thought maybe he got into trouble or something. I never thought that …”

After a pause, she continued: “But I used to tell him, a long time ago I used to say, ‘One day the police are going to come and tell me they’ve found you dead’. I said it just to scare him off, but I never really believed that.”

It was 2am when two police officers came to her door. Bestrin was reluctant to let them in, worrying they would wake the baby in a house where sound travelled easily.

“I said, ‘What’s the matter, is it something bad?’ And they said, ‘Yes, it’s very bad’. I said, ‘OK, come in’.”

Amaru was dead. He had walked into a disabled toilet on the ground floor of Liverpool Hospital at quarter to 11 that morning, where he locked the door and shot up with heroin.

He wouldn’t be found until almost 12 hours later, when cleaners came by and saw the toilet was occupied yet again – they had checked it and left a few times through the day – at 10.15pm. The cleaners unlocked it from the outside, saw a figure slumped between the door and the wall, and called security.

Bestrin, who is well acquainted with death, said she took the news calmly.

“Because I’m a nurse and I work in palliative care, emotionally I always guard myself, you know?” she said. “I have developed this guard. Maybe with my profession, I don’t know. I get some education around death and the grieving process.”

After the two officers left, Bestrin made a cup of tea, and sat alone in her silent house, waiting for the sun to rise.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she said. “It’s like, ‘No, there must be something wrong here’.”

The toilet where Amaru died is just off a busy thoroughfare at Liverpool Hospital, which is the largest hospital in New South Wales. It’s one of two disabled toilet doors you walk past in order to get to the male and female cubicles at the end of a short corridor.

Outside, the public area is a hive of activity, with payphones and a florist on one side, and lifts and a gift store selling baby clothes and toys on the other. People are bustling back and forth, searching the array of flowers for the ideal bunch, waiting for the elevator, deciphering directions to get to the right ward.

It is macabre to think about Amaru lying in the toilet while hospital life went on around him. But it is not unprecedented, or even that unusual. According to NSW Health figures, Amaru is one of six people found dead in a public toilet in a public hospital in New South Wales since January 2015.

His inquest will be held jointly with that of Alan Bugden, who was 66 when he died after being found in a toilet at the Royal North Shore Hospital in August 2015. Bugden is believed to have suffered a stroke in the toilet and was not found for almost a day. He, too, was discovered by a cleaner.

A woman in her forties was found dead in a ward toilet – not a public one – at John Hunter Hospital in May 2016 after she had been missing for almost eight hours. Another woman died after being found unconscious inside a public toilet after she had been discharged from Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in December 2016.

Since Amaru died, Bestrin has visited the disabled toilet three or four times, at first to see where her son passed away, and then to see if anything had changed.

“My point is, how can it be 12 hours that it took to find him?” she said. “It could have been a medical emergency. I don’t know if he died instantly, we’re looking for further information from the post mortem examination.

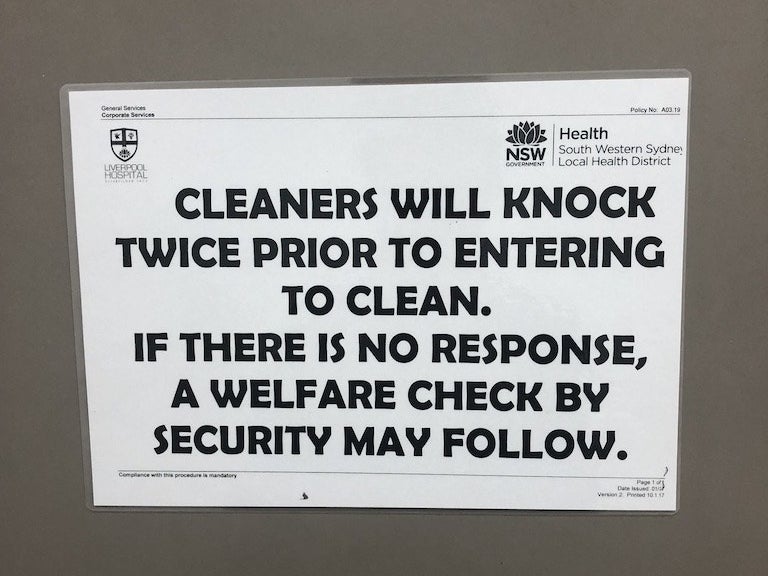

“Every time I have gone back to the hospital to look at the toilets, the only thing that has changed is a sign that says this toilet is going to be checked by cleaners. If there’s no response, we’re going to call security to open the door.

“That’s as far as I can see in regards to measures they have taken.”

In December 2016 every local health district in NSW was ordered to put in place “clear inspection and escalation procedures” for cleaning and clinical staff, a spokesperson for NSW Health told BuzzFeed News.

Cleaners now have to knock on occupied toilet doors, and if they have any concerns about the occupant – for instance, no response – to alert hospital or security staff.

There’s extra signage in public toilets in hospitals, and systems have been introduced for recording which toilets have been cleaned and inspected, and when.

“In NSW public hospitals every year, there are over 1.96 million hospital admissions, 2.78 million emergency department presentations and 12 million outpatient service visits,” the spokesperson said.

“NSW Health has acted to meet the high activity levels by establishing mandatory safety processes and responsibilities into the everyday practices of staff in our public hospitals.”

NSW Health also offered its condolences to the Bestrin and Bugden families.

Bestrin doesn’t think it should be the cleaners’ job to check. The hospital told her that the day Amaru died was an unusually busy one for the cleaners, and she fears the same thing could happen to someone else.

“They said originally they didn’t have any procedures established for checking the toilet, so they added it to the cleaner’s [job] description,” she said.

“I think that’s unfair because they are already overworked and if that happened on that day they were too busy, it could happen again. That’s my concern for the greater community.”

It’s not yet known how Amaru died – whether it was an overdose, a reaction between the heroin and medication he had taken on the flight back from Chile, or something else.

Bestrin describes her eldest son (she has two others – a toddler and a teenager) as an affectionate person. Cooking was his gift. From age 5, Bestrin would turn on the stove for Amaru to scramble eggs. He worked as an assistant chef, and studied commercial cookery. He loved music and sang frequently, and wasn’t one to leave his feelings unknown: He never missed a chance to tell Bestrin, “Mum, I love you.”

He was also addicted to heroin. Bestrin said that when he was under the influence, Amaru was like a different person. He had run-ins with the law ranging from minor – graffiti, a stack of train fines, marijuana possession – to serious. He spent 10 months in prison for a violent carjacking, in which he threatened a terrified driver with a knife and then held up a bottle shop.

Bestrin does not excuse Amaru’s behaviour. She also says it’s time to face facts when it comes to addiction.

“It’s hard enough [to lose your child] in any way, in any possible way,” she said. “But, you know, I was trying my best in helping him. Being a nurse, I try to help people all the time. What an irony in life, that I could not help my own son. That is hard to take. But you just have to accept it.”

Bestrin’s theory is that Amaru wound up at Liverpool Hospital that morning because of its clean syringe dispenser, part of a statewide program to reduce needle sharing among injecting drug users.

As well as changes to hospital procedures, she hopes the inquest might bolster support for a medically supervised injecting room in Sydney’s west, like the one in Kings Cross.

Bestrin plans to attend every day of the inquest, scheduled to begin on Tuesday.

“It won’t bring him back,” she said, but she is hopeful it might bring some change.

CORRECTION

Alan Bugden died at Royal North Shore Hospital after he was found in the toilet. A previous version of this post stated that he died while in the toilet.