I remember clenching my fist as the words “You fucking dirty Indian!” left his mouth.

It was recess, the sun was out, and we were playing a game that was some parts rugby and other parts football. For a split second, I thought about the words and what they meant. What part about me being native made me dirty? I didn’t understand, but it still hurt me. For the first time, I felt ashamed to be who I am, as if somehow his white skin made him superior. The other kids, pretty much all white, stopped playing and stood around in excitement, knowing that a fight might break out. He was tall and round and easily the biggest kid on the field — a farm boy from a nearby town. I marched forward, but before I could land a blow I ended up on the ground, desperately covering both sides of my head as punches rained down. Then they stopped. I looked up to see my friend Arthur, the only other native student in my class, riding the boy like a rodeo bull and landing a few hooks as the boy dropped to his knees.

In the aftermath, only myself and my bully got sent to the principal’s office. A TA that was supervising the recess had seen what happened and let Arthur get off free. I wasn’t surprised. He had a charisma and charm that made him liked by nearly everyone, including the white kids. It was his armour and I had yet to find mine. In the principal’s office, we sat in two separate chairs, side by side, while the principal looked at us from across her desk.

“So what happened?” she asked, her eyes glaring darting back and forth at both of us.

I pleaded my case — he called me a “fucking dirty Indian.” I’m not sure what I expected, perhaps some sort of outrage or at the very least that she would believe me. But her face went unchanged, like the words didn’t mean anything, like they couldn’t possibly hurt someone. The boy was quick to deny my claim: “I didn’t say that!” And I could tell that she believed him, that she was on his side and not mine, and I immediately regretted saying the f-word in front of her. When I realized that I had lost, that nothing I could say would prevent this from happening again, my stomach sank.

This was 2002 and I was 10 years old. It was my first encounter with racism as an Indigenous person in Canada, racism that was perpetuated for hundreds of years, intended to make me feel like there was something wrong with being Indigenous. At the time I was attending a school in Eriksdale, Manitoba, a municipality about 20 minutes away from my reserve along a single-lane road. But it felt like a different world.

I used to think Canada was just Anishinaabe and white. I was young and left my little world only on rare occasions. It’s strange to think about it now, but I believed that beyond our dusty gravel roads there was nothing but white people, white communities, and white cities. I knew there were Indigenous people in Winnipeg, of course — it’s home to the largest urban Indigenous population in Canada — but I was stuck in the childish belief that we were mostly confined to small plots of land known as reserves. I had no contact with them and they had no contact with me, and I thought that’s how it was supposed to be.

I grew up on Lake Manitoba First Nation, about two hours northwest of Winnipeg, if you follow the speed limit. My community, or Dog Creek as it’s often called, begins where municipal pavement turns into loose gravel road. Its uneven roads are elevated like mounds to avoid being washed away by flooding every spring. It’s the type of place where people knew you by what kind of car you drove and who would wave and murmur Aanii, hello, as you drove past each other.

Lake Man, another nickname for our community, is home to about 600 people. My kookoo and shoomis, grandma and grandpa, used to tell me that the land the community lived on was once heavily populated by wild dogs — the origins of the former name Dog Creek. I have no idea if this is true or not, but the community lives up to its name in its absurd number of stray rez dogs.

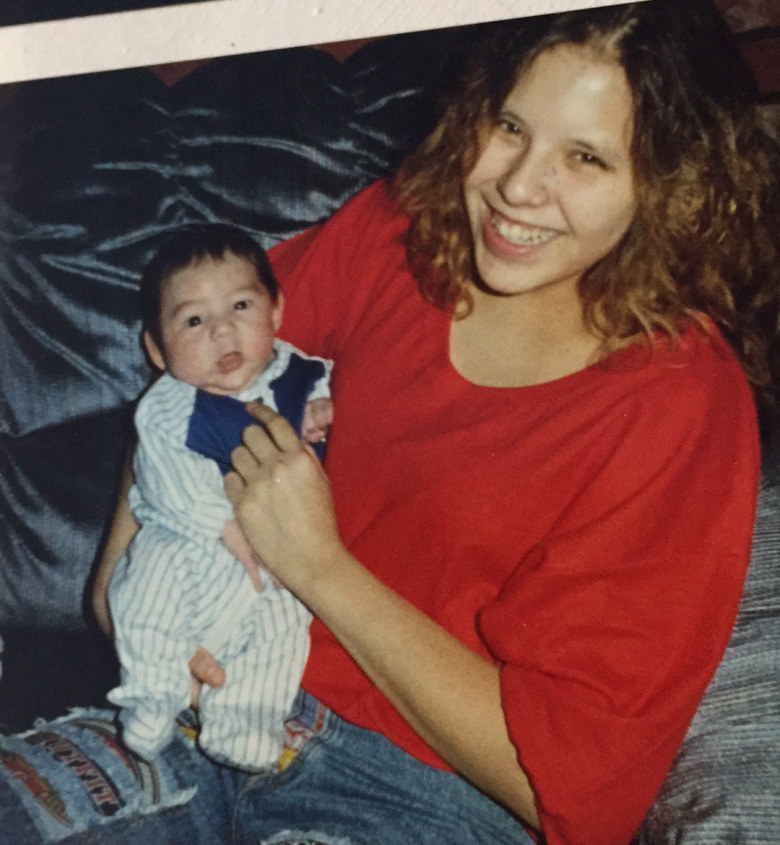

Throughout my childhood there, my family — which included my grandparents, Uncle Randy, and Great-Uncle Ernest — lived in a small row of four houses, almost like a little village. My mother raised my younger brother and me on her own, and had me at 16. Uncle Randy was the closest thing I had to a father — my biological one left when I was just barely forming memories. At times, I loved him more than anyone. He’d play music for me on an old brown record player. “Another One Bites the Dust” by Queen became my first favourite song. Randy graduated from university and came back to Dog Creek to work as a school teacher, before he died from a heart attack at 39 years old. After Uncle Randy died, we moved into his house. It was larger than our little white house, which was never used again. My grandparents still live in the same large brown house, and it has served as a beacon for nearly every family gathering. There used to be a tall teepee beside it and I still have numerous scars on my knees from climbing and falling off trees nearby.

The rest of the community is small, complete with an elementary school, two baseball fields, two slots venues, and one convenience store. Every year my friends and I would look forward to the annual treaty days, a weekend event that celebrated Canada’s treaties with Indigenous people — the benefit of which was standing in a long line and being given a $5 bill and shaking the hand of a Mountie at the community hall. Apart from the money, the real highlight was the competitions. There were canoe races, scavenger hunts, and baseball tournaments, and a powwow on the last day. I was proud to call myself Anishinaabe, to call Dog Creek my home, and the people there my community. I still am. But my pride and everything I believed in about myself and who I was and where I belonged was quickly stolen from me.

I was getting ready to enter grade four when the school in Dog Creek ran out of money to pay for its teachers — or at least educated and qualified ones. The teachers, all of them native, were forced to leave for better pay. My kookoo, who was the librarian, stayed. Students in their high school years were forced to attend school in Lundar, a town not too far from Eriksdale, where stories of racial tension and bloody brawls made their way back to the rez almost daily.

My mom told me I was changing schools, worried my education would suffer. I protested the decision, but I feared the hand of Mom more than anything. She had a toughness about her that I admired, and as a single mother, she rarely took no for an answer.

“You have no choice,” she told me.

I kept quiet, irritated by the fact that I’d have to make new friends.

Annoyed, she continued. “It costs a lot, but you’re going.”

I asked her how much it would cost and she told me that it would be $4,000 per year. “Why do we have to pay?” I asked, aware of the difference between public and private schools from TV shows on the Family Channel.

She looked away, struggling to get out the words of defeat. “They say it’s because we’re not a part of their community.”

What I didn’t know then was that students on First Nations communities receive 30% less funding than those off reserve. In more severe circumstances, the education gap for Indigenous children is closer to 50%. I didn’t know that the tuition fee my family paid was greater than the cost of a single semester at most Canadian universities at the time. Still, I can’t justify the cost of admission at Eriksdale School, where many of its students were, like me, not residents of the “community.”

On my first day of school in Eriksdale, I took a seat near the back of a classroom. A boy, Arthur, turned around from his seat near the front of class and said a line that I knew was slightly paraphrased from the movie Billy Madison: "Man, first, second, and third grade were easy, but this year’s gonna be tough!” The blonde girl behind him smirked in a way that told me they were friends. From the look of his brown skin and short black hair, I could tell he was native, but he was not from my community. He was from Eriksdale and we quickly became friends. We were two of no more than five or six natives there.

During my first recess, I went to the main office and sobbed, claiming I had a sore stomach. I called Mom and she said she couldn’t come get me and that I would have to tough it out. So I did. Arthur helped me integrate, teaching me the language of the white kids, and even had my back when they set out to hurt me. Their main methods were verbal more than physical — declaring, like their ancestors before them, that Indians were drunk, poor, vulnerable, hopeless. I fought at first, letting my hands go at anyone who crossed me. But I quickly realized that was what they expected from me.

There is no other way to say this. But the problem with integration, or assimilation, is that you start to forget who you are. Students looked at me like I survived some sort of natural disaster. I was questioned about my reserve, the vaccination scar I have on my left shoulder, and the alien accent I spoke with. They would ask about my family, what my spirit animal was, why my eyes are shaped like almonds. They investigated me not so much with a welcoming curiosity as they did like anthropologists with an unshakable bias. The teachers at Eriksdale School demanded that we learn one side, only one exalted perspective, of Canadian history and nothing of Indigenous peoples, not even those a few kilometres down the road. And for this reason alone, they knew nothing about me, or us.

The other problem with assimilation is that you begin to feel ashamed about your family, your culture, your language.

I started crafting lies about myself so I could become “one of them.” If Mom ever came to school, I would discreetly tell the other students she was my aunt because, surely, all white kids have two parents. I began to hide or alter the things I loved most about myself and who I was. I lied about my Anishinaabe name, Kabih Niigahnii Aydung, The One Who Speaks First, and what it really meant. I packed my lunches as neatly as possible and made sure I was “clean.”

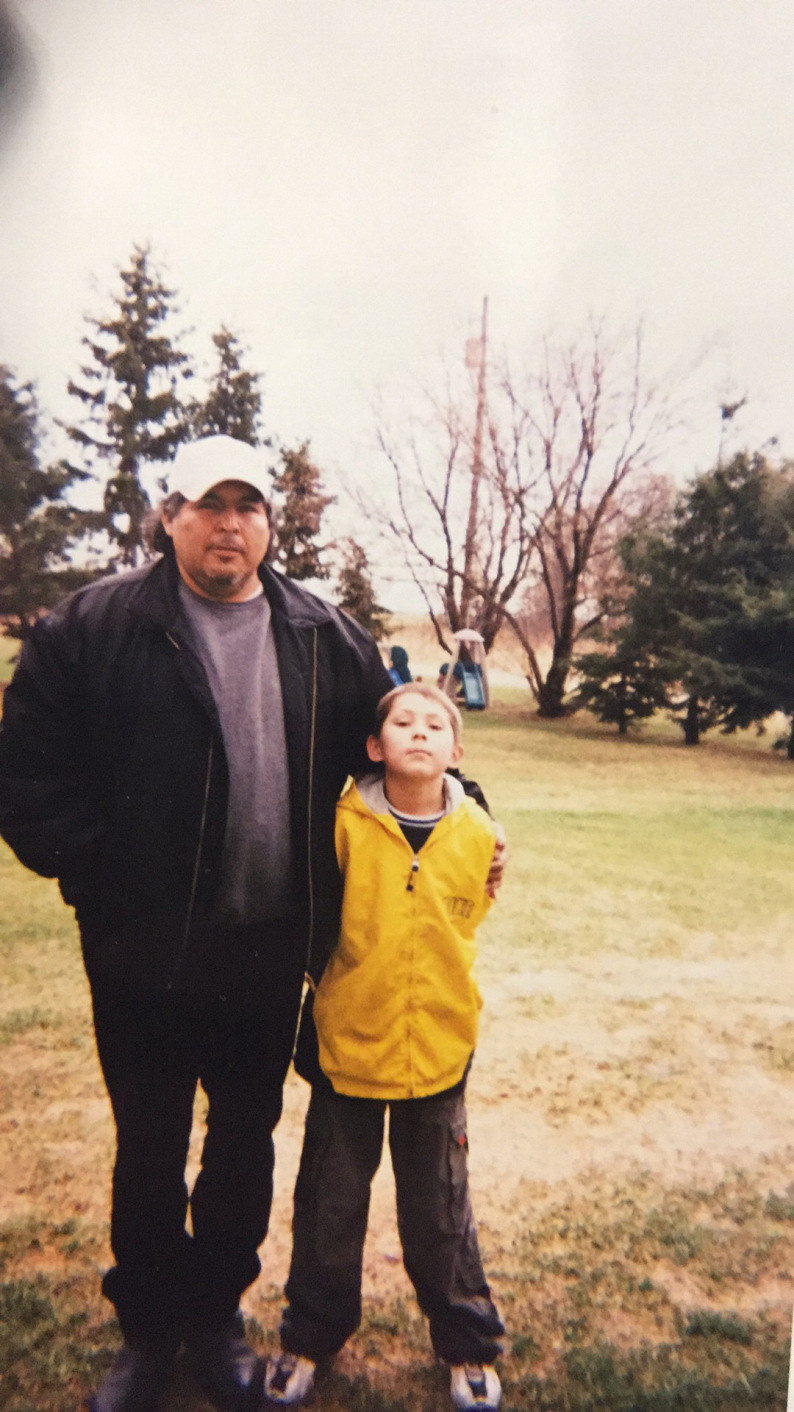

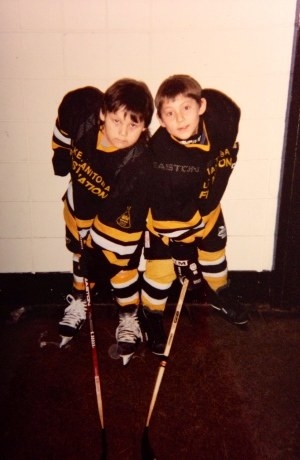

After my first year in Eriksdale, my mom and my brother made the choice to move to Winnipeg so she could finish university. I stayed behind with Kookoo and Shoomis. And they did everything they could to make sure I succeeded. Shoomis put me on a hockey team in another nearby town and ensured I made it to every practice and every game, no matter how late we got home. Kookoo would help me build miniature teepees for arts and crafts competitions in Eriksdale while everyone else assembled Viking ships. Our efforts went unrewarded, but I still cherish one particular teepee we spent hours constructing. It was made out of brown leather and maple twigs with medicine wheels painted on its sides. It looked cozy — still does — sitting on my dresser, and I’d imagine what it might be like to live in it.

Kookoo would wake up at 5 a.m., and I would rise an hour later. She would make me breakfast, warm up the car in the frigid winter, and then take me to meet the school bus. It would be waiting for me at that spot where pavement turns into gravel, and by this time of year it was usually covered by a sheet of ice and snow. Three other native kids and I were the first ones to get picked up and the last ones to get dropped off.

One morning, while on our way to the outskirts of the rez, I asked my kookoo, “Why do you do this for me?” Each breath I took drifted like a smoke signal.

“I just do,” she said, looking at me. “And I’ll keep doing it because I love you, and I want you to have a good education.”

The world outside was white, barely visible and the windows still frozen, except for a small patch on the driver’s side. But somehow she knew where she was going. I trusted her.

As much as I wanted to stand up and educate my classmates at Eriksdale about how much they had benefitted and profited from the Indian Act and the oppression of my people, I couldn’t. Because I realized that, like them, I, too, was privileged. I knew there were First Nations communities in northern Manitoba that had life twice as hard, where children the same age as me had lost hope.

Each student in my class firmly believed they’d some day lace up their skates for an NHL team or graduate from university. They believed they could do anything. And I’ve always envied this about them, but I could never embrace that feeling. Indigenous youth are taught that their lives and their histories are unimportant, that the system didn’t want them here to begin with.

A year later, Mom graduated. While I was in Eriksdale, my community became more distant and I lost touch with people I saw daily. But I don’t blame Mom, because I’d be lying if I said I’m not grateful for what she’s done for me. She now has three different degrees and is a social worker. She believes in young Indigenous mothers; if she could raise two boys so can they, she once told me. This meant it was time for me to leave the rez and join Mom and my brother in Winnipeg.

In the immediate years after I left, I returned home to Lake Manitoba First Nation almost every weekend with my skates and hockey stick. I went to treaty days and hung out with my cousins. We played pool, gambled for money with marbles, and flew through the bush on ATVs. I never felt the need to try to fit in or act a certain way. We made jokes that only we could understand. Any lingering shame I carried was lifted from my shoulders, if only for a brief moment.

I stopped fighting with my fists in my first year of high school. I fought three times that year. One day, the only native teacher in my school, Wade Houle, pulled me aside and projected the number of fights I might have on my record by the end of my scholastic career.

“If you keep doing this, you’ll have about 15 fights,” he said. I looked down in embarrassment.

He told me there were other ways to fight. That I could start by reclaiming my Indigenous identity and embracing our cultural teachings. I hung on every word, as if I had been waiting for this message for years. For a stretch of my childhood, I felt ashamed of myself, but those feelings have slowly faded away since my time in Eriksdale. Over the years I have tried to be more involved in the Indigenous communities I am welcomed in. I’m proud to be Anishinaabe, and how could I not be? We are still here, fighting for our communities and the land we live on.

I miss my rez a lot more these days. I moved to Toronto four years ago and graduated from Ryerson University, and I have travelled and studied abroad. At times it can be difficult roaming the big city and seeing nobody that looks like me, and the moment you do it’s like spotting an old friend. But the more I have searched, the more Indigenous circles I have found. I continue to learn more about my culture through ceremonies and sit down in a sweat lodge every Wednesday to pray and reconnect to the land.

In 2004, on the day I left my community for Winnipeg, I packed only what I needed. I made sure to leave some things behind because I knew I would be back regularly. The house smelled of Kookoo’s apple pie, ready for me to take to my new home. And now whenever I go back there’s usually a fresh one waiting.

Kookoo hugged me, keeping her composure. She stayed behind in Dog Creek because she has never wanted me to see her cry.

Shoomis was driving me to Winnipeg in his truck. He would rotate one hand on the steering wheel, while the other squeezed a hand gripper. He is a spiritual healer for Indigenous inmates at Manitoba’s largest provincial prison. Years ago, when Indian agents knocked on his family’s door, he and his siblings were hidden to avoid residential school, but he was forced to attend when he was a teenager.

I asked him a question I often thought about: “Why do native people struggle?”

He said that it was a cycle and that families are hurting from the pain inflicted on them in the past and present.

He paused and said, “But never be ashamed to be Ojibwe, my boy.”

I promised him that I wouldn’t.