Two rival Persian Gulf nations have for the past year been conducting a tit-for-tat battle of leaked emails in US news outlets that appears, at least in part, to have been an effort to influence Trump administration policy toward Iran.

The leaks often have set the news agenda in Washington, leading to dozens of news stories. But there’s been little attention paid to the regional rivalry behind them.

On one side is the United Arab Emirates, a wealthy confederation of seven small states allied with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s bitter foe. On the other is Qatar, another oil-rich Arab monarchy, but one that maintains friendly relations with Iran, with which it shares a giant natural gas field.

Ironically, both are US allies, with Qatar providing a base for US aircraft flying missions in the Middle East and the UAE contributing pilots and planes to the anti-ISIS coalition.

The unfolding battle alarms transparency advocates who fear it will usher in an era in which computer hacking and the dissemination of hacked emails will become the norm in international foreign policy disputes.

“It is a troubling development that US partners now appear to be deploying the same sorts of tools that authoritarian regimes such as the Russians and the Chinese use against internal opponents of their regime or external opponents,” said Jamie Fly, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund and a former foreign policy adviser to Florida Sen. Marco Rubio. “It appears that the perception even among friendly countries is that such action is now legitimate and will go unpunished by US authorities, which is a dangerous state of affairs.”

Noah Pollak, the director of the Committee for Israel, which lobbies on Middle East issues, said the allure of such a campaign is almost irresistible. “It's so low-cost yet so effective at knocking someone out of the game and embarrassing one side in a political fight,” he told BuzzFeed News. “You could spend years campaigning traditionally against someone or you could hack an email account and leak salacious details to the media. If you have no scruples, and access to hackers, the choice is obvious.”

How the leaked materials are distributed to reporters remains largely opaque. One reporter for a national organization recalls feeling unsettled when he discovered a set of documents on his desk in October 2016. There was no information about who had left the documents, just that they concerned an Iranian-American businessman named Farhad Azima. Googling the name, the reporter found scattered blogs with titles like “Farhad Azima Scammer” and “Farhad Azima Scams” that had cropped up in August and September of that year, garishly filling each post with hashtags to improve search results and linking to empty torrent files.

“It seemed like something more convoluted than I had the bandwidth to pursue at the time,” said the reporter, who, because of the shadowy nature of the leak, would speak about the tip only on the condition of anonymity.

For the next eight months, he forgot about the Azima tip — until June 21, 2017, when the Associated Press published an explosive story: “Wall Street Journal fires journalist over ethics conflict.” The story was based on years of emails exchanged between the journalist, Jay Solomon, and Azima, one of Solomon’s sources, and included Azima’s offer for Solomon to join his proposed spy plane company, though the company never got off the ground and Solomon said he never agreed to the venture.

How the information reached the AP reporters is not publicly known; the reporters declined to talk to BuzzFeed News, citing the need to protect their sources.

The story had immediate ramifications for its two subjects.

Azima, who friends say has had trouble securing new business since the AP coverage, told BuzzFeed News that it’s been difficult to recover from the leak, which also formed the basis for an AP story about his business ties going back decades. “The reputational damage is immeasurable,” he said. “I cannot begin to tell you how difficult it has been. This is the new warfare. This is something the governments use for commercial reasons, use for political reasons, and use to destroy their opponents.”

A tit-for-tat battle of leaked emails that has raged for the past year in US media can be traced to two Persian Gulf rivals intent on influencing Trump administration policy toward Iran.

For Solomon, who was fired for not telling his bosses about Azima’s business offer, the episode is doubly worrisome because he cannot tell if he was targeted and, if so, by whom. The emails seem to have emerged entirely from Azima’s inbox, making it possible Solomon was just collateral damage. He has no evidence that his own email account was hacked.

“You’re dealing in a national security realm where there’s so many murky players, and then suddenly to have this stuff slowly creep out, then it’s being distributed in such a coordinated way to the media — it’s terrifying,” Solomon told BuzzFeed News.

“Some of those emails look stupid, but I think anyone, if they’re gonna get hacked, they can make you look like a nefarious character if that’s their intention,” Solomon said. “You just don’t know what’s real and what’s not. How do you even respond when you’re being targeted by this dark world you don’t understand?”

Tensions have been building for years between the UAE and Qatar. The two have feuded over Qatar’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist movement that many Persian Gulf monarchies see as a threat to their hereditary kingdoms. They’ve also been at odds over Qatar’s friendly relations with Iran and its backing of the Al Jazeera television channel, whose newscasts are often critical of Arab autocrats.

The feud broke into the open on May 24 last year when someone hacked into the website and Twitter account of Qatar’s government news agency, QNA, and posted news stories and tweets that quoted the country’s emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, making bizarrely pro-Iran statements.

Qatar disavowed the remarks within an hour, and its foreign minister, Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, quickly texted the UAE’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed, that the statements weren’t true. Qatar took its official news website down, and still hasn’t brought it back online.

But the damage had been done: The UAE and Saudi Arabia, with the backing of the Trump administration, used the hacked news stories as a pretext for severing relations with Qatar, imposing a blockade, and making 13 demands, including that Qatar cut all ties with Iran and shut down Al Jazeera and all other state-funded news sites.

“They weaponized fake news to justify the illegal blockade of Qatar,” said Jassim Al Thani, Qatar’s Washington-based media attaché. “In the year since then, we have seen their repeated use of cyberespionage, fake news, and propaganda to justify unlawful actions and obfuscate underhanded dealings.”

Qatar asked the FBI and British intelligence to help it investigate the QNA hack. In July, US officials said US intelligence monitoring had captured senior UAE government officials discussing the hack the day before it happened, and the FBI concluded that freelance Russian hackers had carried out the operation on the UAE’s behalf.

“You’re dealing in a national security realm where there’s so many murky players ... it’s terrifying.”

Those conclusions were ironic, if nothing else. The Trump administration initially supported the anti-Qatar campaign, siding with Saudi Arabia and the UAE in the blockade, to the dismay of key Trump administration officials, including then-secretary of state Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, both of whom pointed out that Qatar hosts the US Air Force’s 379th Air Expeditionary Wing at its Al Udeid Air Base, the largest military airfield in the Middle East.

After a fierce public relations campaign that included a visit to the White House last month by the emir of Qatar, US zeal for the blockade appears to have faded; President Trump’s new secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, reportedly asked Saudi Arabia to end it during an April 28 visit to that country. The Saudis have not responded publicly to that request.

Azima has no doubt about who targeted the email account from which his back-and-forth with Solomon was taken — he’s filed a lawsuit in Washington federal court accusing the state investment fund of Ras al-Khaimah, one of the UAE’s seven emirates, of engineering the hack — a claim the government of Ras al-Khaimah calls a "complete fiction."

In an emailed statement, the emirate said Azima's lawsuit was an "attempt to frustrate a legal proceeding in the United Kingdom" that accuses Azima of bribery and other charges. "Mr. Azima’s claim in the United States case that (the investment fund) or its agents hacked his computers and put his information on the Internet is a complete fiction," the statement said, adding that it was only after Azima's emails were posted that "its representatives became aware of material on the Internet that suggested Mr. Azima had behaved improperly."

In his suit, Azima traces the hack to his role in mediating a dispute between the fund and its CEO, who Ras al-Khaimah claimed owed the fund $4.5 million.

The negotiations fell apart, however, and Ras al-Khaimah blamed Azima and demanded he pay the emirate’s fund $4,162,500. After Azima balked, the fund sued him for $2.6 million in October 2016.

But the hacking effort predated the collapse of the talks, according to experts Azima hired to pursue the case. They found evidence that someone had been peppering him with spearphishing emails since 2015, instructing him to click and give his password to a fake log-in site. He fell for them repeatedly, giving away his log-in credentials.

Azima’s Hotmail account was hacked on Aug. 7, 2016, his lawyers say. Over the next two months, someone created several WordPress and Blogger sites with names like “Farhad Azima Scammer” and “Farhad Azima Scams,” and posted links to torrent files, though for months, the files were useless, as no one “seeded” them with the original emails. That changed sometime in early 2017, when emails from Azima’s account began flowing into them. One torrent file bore the name “Fraud Between Farhad Azima and Jay Solomon.”

In June of last year, someone began leaking the contents of a Hotmail account belonging to Yousef al-Otaiba, the UAE’s flashy ambassador to the United States. The leaks were distributed to a group of online news sites, including the Huffington Post, the Intercept, and the Daily Beast.

“The leakers claimed the documents had been provided to them by a paid whistleblower embedded in a Washington, DC, lobbyist group, though it’s clear from even a cursory examination that they were printed out from Al Otaiba’s Hotmail account,” reported the Daily Beast.

Whoever sent those emails tried to appear Russian. They called themselves “GlobalLeaks” and made explicit references to DCLeaks, a site Russian military intelligence created in 2016 to leak emails hacked from both Democratic and Republican party officials.

Initial reports from the Daily Beast and the Intercept referred to GlobalLeaks as “hackers.” But whether Otaiba’s email was hacked remains an open question. Some of the leaks’ contents were clearly printouts of email messages. “It’s not clear whether Otaiba’s inbox was hacked or passed along by someone with access to the account,” said a later Intercept story.

Based on the stories they generated, the purpose of the leaks was to question Otaiba’s value as the UAE’s representative in Washington — a position that arguably might help Qatar. An August story in the Intercept noted the contradiction between Otaiba’s hard-partying life in the US and the UAE’s strict social policing. Another claimed that Otaiba had been critical of Trump at the same time that he was pressing his country’s campaign to isolate Qatar.

Wrote the Huffington Post: “The leaker or leakers who shared the messages claimed they wanted to expose the two-faced nature of the Emirates’ foreign policy. The source has denied having links to Qatar.”

News pulled from Otaiba’s emails appeared to dry up after the final Intercept story. A week and a half after its publication, someone registered otaiba-inbox.com as a central repository of remaining Otaiba files, including pictures of him dancing with women and scattered other emails. By November, according to the Internet Archive, the website was suspended.

The UAE didn’t respond to request for comment.

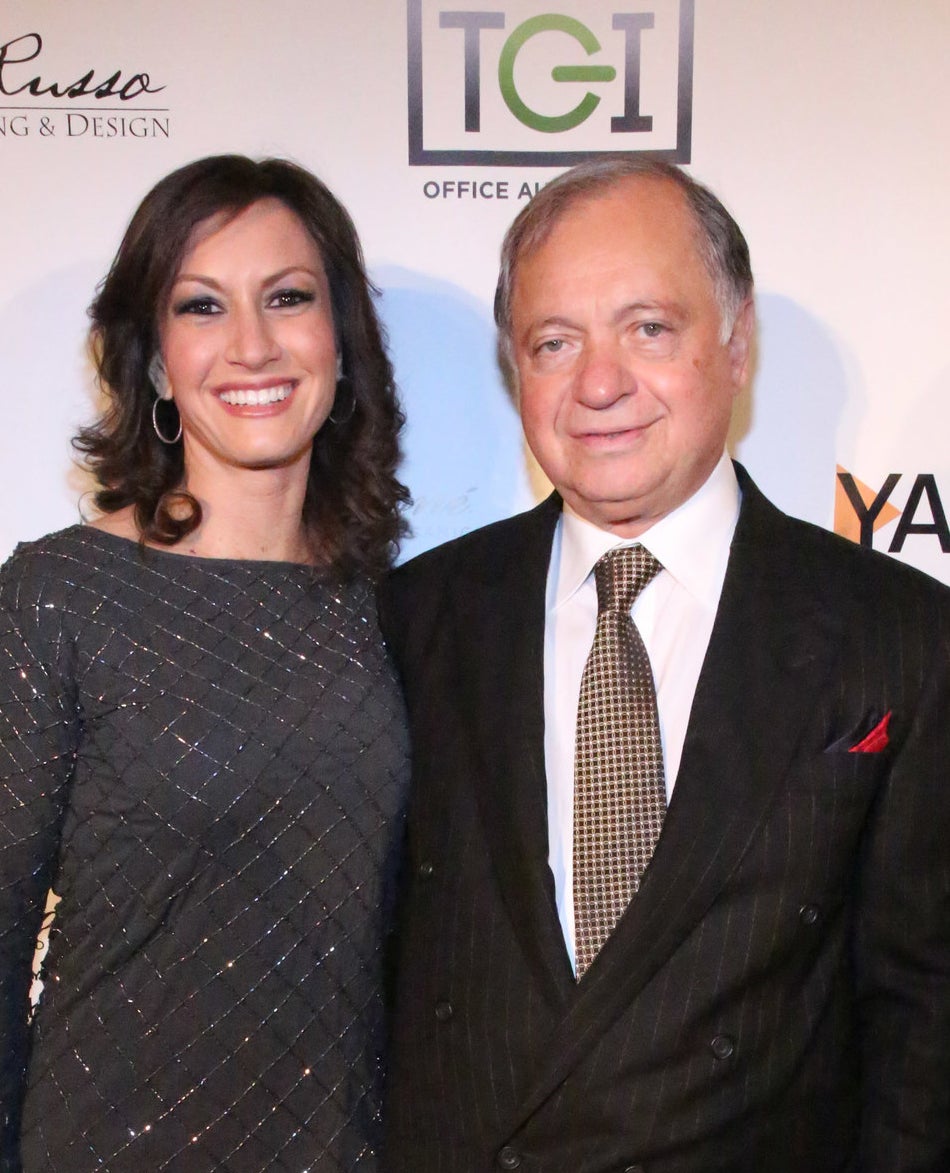

The most damaging email leaks came in March when someone went after Elliott Broidy, a 60-year-old American hired to lobby for the UAE, and whose company, Circinus, has received more than $200 billion in defense contracts from the country. In recent years, he’s been one of the loudest American voices against Qatar, employing tactics ranging from anti-Qatar op-eds to personally lobbying Donald Trump to support the blockade against it.

Broidy was in a prime position to lobby the president. He was the Republican Party’s vice chair of fundraising until April 13, when he resigned after the Wall Street Journal revealed that he’d used Trump’s lawyer, Michael Cohen, to pay a 34-year-old former Playboy model $1.6 million in hush money after he’d gotten her pregnant. The Journal said leaked emails played no role in that coverage.

But there were plenty of other stories that came from Broidy’s inbox, which hackers apparently accessed after tricking his wife into providing credentials to access Broidy’s email accounts and the email server of one of his companies, Broidy Capital Management.

The leaks have been distributed to a group of news sites, including the Huffington Post, the Intercept, and the Daily Beast as well as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal.

By late February, someone identifying themselves as “L.A. Confidential” — later, it was “Hollywood Leaks,” both presumably references to the fact that Broidy lives in Southern California — began sending journalists particularly damning emails. They often, but not exclusively, used ProtonMail email addresses, a popular choice for both hackers and privacy advocates because its owners base their operations in Switzerland, where it’s harder for the US or European Union countries to compel the company to disclose user information. In at least some cases, they then deleted that email address, and the reporters who tried to follow up with questions were left with no means to contact them.

On March 1, a Wall Street Journal reporter who had written in November about a scandal surrounding a Malaysian investment fund wrote that Broidy had stood to make tens of millions if the US Justice Department dropped an investigation into the fund.

Two days later, the New York Times wrote a long account of Broidy’s partnership with George Nader, a former Trump adviser and convicted pedophile who has been questioned in special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 US election. The Times story noted that the sourcing material for that story “was provided to the New York Times by someone critical of the Emirati influence in Washington.”

Two days after that, the BBC reported that Broidy had urged Trump to fire then-secretary of state Tillerson for his opposition to the UAE-Saudi Arabia blockade of Qatar.

Ben Wieder, a reporter for McClatchy who had previously written about how a business Broidy ran in Romania got a boost after Broidy helped introduce a politician there to Trump, received emails Broidy sent to California Rep. Ed Royce, the chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, concerning a trip Royce took to Romania.

“There was thought and calculation behind how this material was being distributed,” Wieder, who wrote about the emails in a follow-up story, told BuzzFeed News. “It’s not the old-school, WikiLeaks, ‘everything’s up on a site; make what you will of it.’”

In March, Broidy sued Nicolas Muzin, an American lobbyist paid by Qatar, as well as the state of Qatar itself, describing the hack and leaks as “a hostile intelligence operation” and saying Qatar, either “by itself and/or through its agents, unlawfully hacked in to the email accounts and computer servers.”

But the leaks have continued: On April 20, the Intercept published a story based on stolen Broidy emails showing that he had offered Novatek, a Russian gas company, $26 million to implement a plan to get it off the US sanctions list.

For many reporters, stolen emails are fair game for a story, even if there’s an indication they were acquired illegally and to further someone else’s cause, as long as they’re newsworthy and it’s possible to verify them.

In an interview with National Public Radio’s Terry Gross, David Kirkpatrick, the New York Times reporter responsible for some of the first and most explosive reporting on Broidy, said that “if the information is newsworthy, we should publish it. You know, our allegiance is to our readers. And we serve our readers. And if we were to start rejecting information from sources with agendas, we might as well stop putting out the paper.”

Jerry Ceppos, the dean of the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University and a longtime news executive, said he sees nothing unethical about publishing news stories from hacked content if the hacked content has been authenticated and reporters give as much detail and context as possible about where the emails came from.

“I think if we tell the reader as much as we know, that it’s probably OK to use the material,” Ceppos told BuzzFeed News.

“It amazes me that the people writing the emails haven’t caught on to the fact that, gee, you need to be a little careful about what you put in,” Ceppos said. “It clearly is going to keep going on.”

But the tactic is controversial for some — echoing, they say, the tactics used against Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. The issue recently was the subject of Twitter posts by two Washington-based political reporters:

Unknown parties -- alleged to be Quatari hackers -- have recently been sharing with reporters the personal e-mails of the RNC's now-former deputy finance chair, likely in an effort to shape our Gulf policy. I do not see much ethical handwringing about it from liberals on Twitter.

Dems are too busy disseminating the undeniably newsworthy stories produced from the stolen @Elliott_Broidy emails to express qualms about the ethics of using them — much like the Republicans who gleefully seized on the newsworthy revelations from @johnpodesta & @dnc @wikileaks. https://t.co/w7WBo5j3W1

Yet it seems unlikely that the use of hacked emails will slow. On April 28, the Washington Post used apparently hacked communications to report new details of a story that had been told a month earlier in the New York Times.

In 2015, at least 25 Qataris, including nine members of the royal family, were kidnapped in Iraq. After confiscating at least $275 million in cash that Qataris had tried to bring through the Baghdad airport, the Iraqi government successfully negotiated the kidnapped Qataris’ release.

What was unique about the later story was that it relied on a cache of phone and text messages that “were provided to The Washington Post by a foreign government on the condition that the source not be revealed,” the paper said.

The Post story hinged on one important detail: whether Qatar had provided millions of dollars to terrorists thought responsible for the kidnapping — a detail that is of immense importance in the region’s politics. When the blockade began against Qatar last year, one of the accusations, seconded by the Trump administration, was that Qatar had provided money to terrorists.

In a letter to the editor published by the Post on May 3, Sheikh Meshal Bin Hamad Al Thani, the Qatari ambassador to the US, accused the Post of using stolen materials to push the idea that Qatar had paid a ransom to terrorists, “a false narrative created by an unnamed foreign government.”

“Why did this unnamed government not share these materials during the abduction (which would have been helpful to a resolution)?” he wrote. “Qatar successfully secured the release of the abductees by working with the Iraqi government.”

Ambassador Al Thani did not identify which country he thought had leaked the materials to the Post. But he noted in his letter that “one of the blockading countries” had asked the UN Security Council in June 2017 “to investigate whether Qatar had paid a ransom for the abductees’ release.”

“The Security Council did not take up the baseless claim, and no country put forth evidence,” Al Thani said.

But the description of the UN request matches a request last year by Egypt, which receives billions in aid from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, for a UN inquiry into whether Qatar had paid off a terrorist group in Iraq. Egypt also backs the blockade of Qatar. ●

UPDATE

This version includes a response from the Ras al Khaimah Investment Authority to Azima's US lawsuit.