Halfway through his second set at the DC Improv in Washington last December, Gary Owen dropped a Cosby joke.

The room was packed. Owen’s originally scheduled six shows sold out so quickly that the club added four more, and those sold out too. It was Saturday night and the crowd was decked out, heavy imported leather coats draped over chairs in the dimly lit venue. Nearly everyone there was black. Except for Owen, who is as white as the Easter Bunny.

Owen wore a brand-new, $250 gray polo shirt, crisp jeans, and camouflage Del Toro high-tops, and he prowled around the stage as he worked. Servers bustled trays of chicken wings and Hennessy cocktails. Owen's road manager was setting up a merch table in the back of the club’s cramped lobby where Owen would sell “Black Girls Rock!” T-shirts along with $20 DVDs after the show.

Mixing good cheer and a touch of self-deprecation, Owen told tales about his wife, who is black, his children, and that familiar comedic fallback, sex. One had him at basketball star Dwyane Wade’s wedding a few months earlier, and standing at the urinal next to LeBron James, unable to resist sneaking a glimpse. “They don’t call him the king for nothing,” Owen chirped.

As a topic for humor, Bill Cosby felt like something else altogether, and a queasy tension sizzled across the room as Owen spoke his name. Somewhere a man grunted, a guttural question mark that sounded slightly menacing. Not even a month had passed since decades' worth of sexual assault allegations against America’s most important African-American comic began resurfacing. Just 12 days earlier, a grand jury in Ferguson, Missouri, declined to indict the white cop who killed Michael Brown. Three days before the show, another grand jury elected not to charge a white NYPD patrolman in the choking death of Eric Garner. It seemed far too soon for a blond, blue-eyed comic from the Midwest to mock a cultural icon in front of 300 black people in the heart of the Chocolate City.

But it turned out to be a carefully calibrated head-fake: Owen’s bit wasn’t about race at all. Instead, he riffed on the apparent agelessness of all the women coming forward to accuse Cosby. “Bill Cosby has the dick of life,” Owen guffawed. “His dick will cure Alzheimer’s! He’s got some Benjamin Button dick! You’ve got six months to live unless you want to fuck Bill Cosby. Then you’re good.” He had made, essentially, a rape joke. But in front of this crowd, at that moment, it somehow felt like safe ground, and the tension in the room boiled off in a burst of gleeful laughter.

Gary Owen almost went there but couldn't.

Owen holds the distinction of being the only white comic to host the influential BET comedy show Comic View and has appeared in shows and movies with Tyler Perry, Eddie Murphy, Jamie Foxx, and Kevin Hart. For the past several years, he has headlined Shaquille O’Neal’s All Star Comedy Jam, routinely sells out 2,000-seat venues, and is currently touring arenas with Mike Epps. In January, his seventh comedy special, I Agree With Myself, premiered on Showtime.

He is, of course, far from the only Caucasian ever to make black people laugh, but it’s difficult if not impossible to think of other white comics who play almost exclusively to African-Americans — and, in particular, one who has found such a strong base of support among black women.

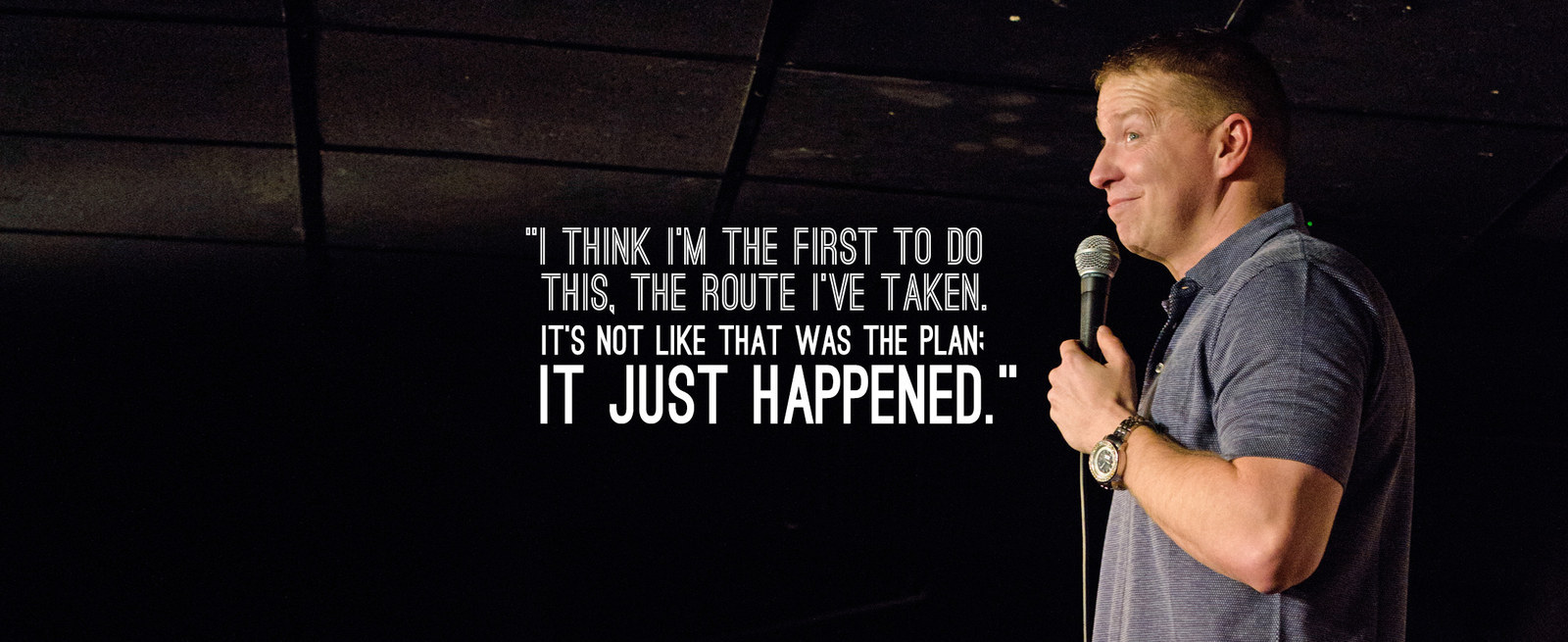

“I think I’m the first to do this, the route I’ve taken,” Owen said recently while trudging across the Paramount Pictures lot in Hollywood. He was there to film a guest appearance on Real Husbands of Hollywood, a hit BET show starring Hart. “It’s not like that was the plan; it just happened.”

He never says the n-word; he constantly reminds audiences he has a black wife; he tiptoes around societal problems and makes sure even the gentlest critique is tempered by an unvarnished, flag-waving admiration of black culture.

“There’s a couple of things about black people that bother me that I’d like to share,” he often confides, slowing his pacing to deliver what sounds like a trigger warning. But of course it’s a trick: He’s just going to tease them about how long black church services are, or what a saga it is to get a simple haircut at a black barber, or how distasteful chitlins are. These jokes are not judgments, they’re winking affirmations.

And yet, he can never be more than an outsider. The day after the Ferguson grand jury news in November, Owen posted on Facebook and Instagram that the situation was “bringing out the worst side of” people and that he wasn’t sure Michael Brown was completely innocent. “I don’t know anyone who gets shot doesn’t have a gun then decides to come back towards someone who just shot them.” The post, and a follow-up, generated fierce pushback.

“Yea he has a Black wife and stars in a lot of Black Films but at the end of the day, he wasn’t raised Black,” one commenter wrote. Added another, “Bro just shut up. Black people are ur only fans ur about to lose them all.” And a third: “Stay in yo lane.”

At 41, Owen is unquestionably successful. By his own account, he made over a million dollars last year, which goes a long way in southern Ohio, where he lives. He can tour as much as he’d like, is a close friend to Hollywood celebrities and star athletes, and he and his family want for nothing. Still he yearns for more, for the the kind of widespread recognition that any ambitious performer covets.

“I just want a big HBO special or a network or somebody willing to get behind my work and promote it,” said Owen, who had been pitching a sitcom idea while in L.A. “The most frustrating thing for me is to have this successful act that resonates across the country and the network guys just don’t get it. Everyone sees it except them. I want to leave a mark.”

For all the work he’s put into building trust with his audience, Owen will never be a black comic or be able to carry a black movie; he’ll always be some version of the goofy white sidekick he plays in the two Think Like a Man films. In two decades of comedy, he has built no white following — among audiences or even fellow comics — and made little sustained effort to do so. He has little choice but to stay in his lane, and he's the only one in it.

So he sits in limbo, bound by his respectfulness to a culture that can never completely be his; some argue he'd have more of a career if he pissed people off. "He's not successful enough to really pull out the haters yet," said producer Will Packer, who cast Owen in the Think Like A Man movies as well as Ride Along. "When he really blows up, the haters will come out, because that's how it works."

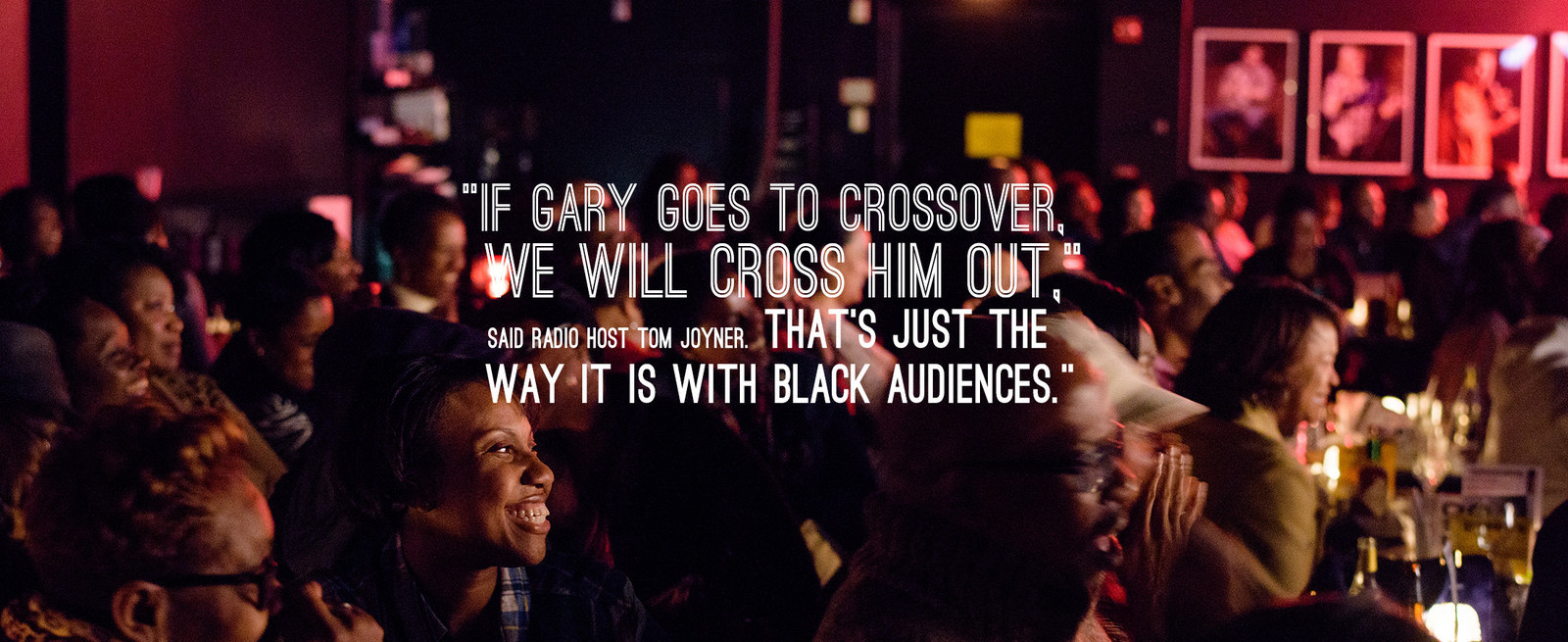

But the mere notion of attempting to blow up carries its own risks. “If Gary goes to crossover, we will cross him out,” said Tom Joyner, host of a radio show that’s syndicated in nearly 100 markets, and on which Owen appears weekly. “That's just the way it is with black audiences.”

Owen’s Instagram overflows with photos of him standing next to professional athletes, towering men wearing grins on their faces as they put their arms around the funny white guy they just saw perform.

But in person, Owen turns out to be surprisingly large — over 6 feet tall with a muscular build that he attends to in a mirrored gym in the basement of his home north of Cincinnati. Compared with other comics, Owen looks like a linebacker, and so his handshake, limp as a wet towel, comes as a surprise. “Hi, I’m Gary,” he said tentatively, standing outside the soundstage where Real Husbands shoots, eyes cast down. As athletic and likable as he is onstage, in person he proves laconic, slow-moving, and sometimes standoffish.

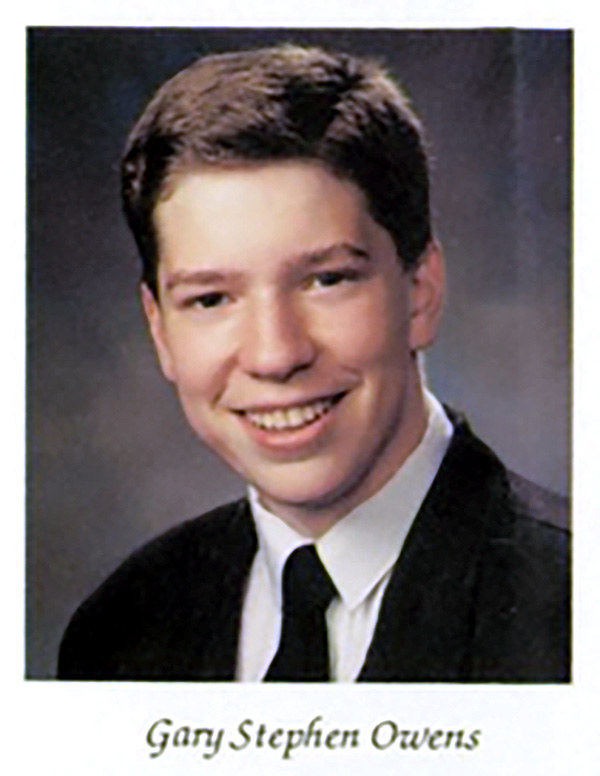

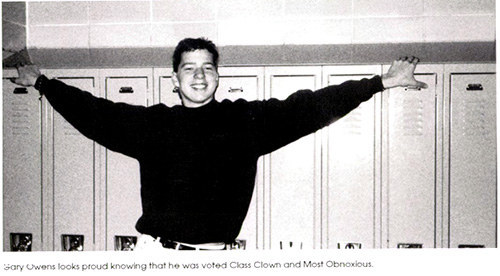

Childhood friends describe Owen as a late bloomer, a scrawny kid. He went out for sports, but wasn’t much of an athlete, playing on the JV football squad even as a senior. Schoolmates picked on him for that, and for the fact that he never had a girlfriend, and because he never had nice clothes, and especially because he grew up poor in a forlorn trailer park in the outskirts of Oxford, Ohio, a college town where class divisions felt particularly sharp.

His mother, Barb, had him at 18 with her high school sweetheart Gary Owens (Owen changed his last name to avoid confusion with the late former Laugh-In comic). They separated a few years later and Barb soon remarried, moving from Cincinnati to Oxford when Owen was 10 with her second husband, Rod Randall. Owen’s father was almost never around, and he spent the rest of his childhood crowded into a double-wide mobile home with his mother, three young half-siblings, an older stepsister, and his chronically underemployed stepfather.

These days, the trailer park is called Island Lake Mobile Home Park (manager’s current special: “Move your home to Island Lake and we will pay for the move and setup of your home”), and there is indeed a muddy pond with a mound of weed-crowned mud poking out of it on the far side of the property.

When Owen was a teenager, this place was nameless. Driving up its potholed road in his sleek, leather-lined Audi A8 on a recent Sunday, he rolled down the window and eyed a new generation of kids growing up like him, in patched thrift-store parkas and ill-fitting jeans, squatting in the grit. His old house was painted blue, with a sagging porch under which piles of junk lay scattered.

“This was the worst place to grow up,” Owen said, rolling the window back up and squinting through the tinted windows. “Humiliating.”

On Friday nights, Owen would slink out through a copse of trees and tall weeds to Highway 27 where he would wait for his friends to pick him up at a run-down old gas station called Jamie’s Market. When it was time to go home, he’d ask to be dropped off there as well, because he didn’t want people to see where he lived, or have to deal with his stepfather.

“Rod,” Owen said, stonily, “is an asshole” prone to frightening fits of rage, who punched Owen’s real father at Owen’s wedding; “a lazy motherfucker” who never held down a job for more than a few weeks, yet harangued his teenage stepson constantly to get a job; a “functional bigot” whom Owen won’t let get close to his own children to this day.

“Gary would volunteer for everything so he wouldn’t have to go home,” said Mike Heineman, one of Owen’s best friends growing up, now an insurance salesman in Kentucky. Sometimes Owen would just run away. “He called me one night and asked me to pick him up. I pulled up to the store and he jumped out of the bushes and got in my car. He spent a week at my house.”

Paul Johnson was one of the only black kids at Owen's high school, Talawanda in Oxford, which had over 1,100 students — the kind of place that still had sock hops. They met after Owen ogled a red, green, yellow, and black leather Pan-African medallion that Johnson wore around his neck, an emblem popularized by the Afrocentric movement in the late 1980s and glamorized by hip-hop artists.

“Gary was just in awe of it. The first thing he asked was, ‘Can I wear that?’” Johnson recalled. “I don’t know if it was so much of his understanding what it meant or trying to identify. He just thought it was cool and wanted to wear it.”

Owen’s mother, Barb, has worked at a factory making electrical connectors for 37 years and eventually saved up enough to buy a proper house a few miles closer to central Oxford. Not long ago, Owen surprised her with a brand-new Hyundai. “I got one of the little ones in a feminine, light-blue color so that Rod wouldn’t drive it,” he said, passing by the squat red brick house without slowing down. “I haven’t been in that house for five years because of him.”

Owen was voted class clown his senior year, but he didn’t watch a lot of comedy growing up and can only remember listening to a Sam Kinison tape on his friend’s car stereo and maybe a few Eddie Murphy bits on TV. He said he was interested in the idea of stardom, but without any real plan or experience performing, Owen enlisted in the Navy midway through his senior year. “I had to get out,” Owen said in an appearance on the The Late Late Show With Craig Ferguson. “I didn't want to be some proud American and serve my country. I just wanted to get out of the trailer park. That was my only goal in life.”

In Gary, the sitcom Owen was pitching, he’s married to a black woman and lives across the street from her well-to-do parents. Gary also features a bigoted father character who lives in a trailer that’s plugged into the house, siphoning its water and electricity. “It’s a metaphor,” Owen said. “He’s sucking the life out of me.”

Barb refused to put Rod on the phone for an interview, saying only that she wished things were different. Then she changed the subject and told a story about Owen at 12, when he got hold of a VHS recorder at a family Christmas party. He “taped himself saying he was going to California and make it big, and all the girls were going to love him,” she said, pausing for a moment. “Everything worked out the way he wanted.”

It was in the Navy that Owen became a fan of the HBO show Def Comedy Jam, which helped launch the career of many leading black comics. “On Friday nights, we’d all sit around and watch it, and we’d never go out until it ended,” Owen recalled. “When I saw the way the crowd reacted, I thought, Oh, that’s the shit I want.”

When he visited family in Ohio on leave, he started hanging outside a local comedy club owned by former Family Feud host Ray Combs. Owen was too young to get in, but he’d stand by the door and listen to the routines and was occasionally let in by a sympathetic bouncer. “I knew I was better than whoever was performing,” Owen said.

Owen spent two years in the Honor Guard in Washington, D.C., and then trained as a Master at Arms, the Navy’s military police, which brought him to a base in San Diego.

His first-ever show was in 1995 at the Comedy Store in La Jolla, an upscale beach town north of San Diego that’s dotted with second homes of people such as Warren Buffet, Mitt Romney, and John McCain. “I was 19 or 20,” Owen recalled. “It was an open mic and there were maybe 20 people in the audience — 10 were comics and they were heckling me. So I told them I was underaged and had been drinking all night long. Shut the place down.”

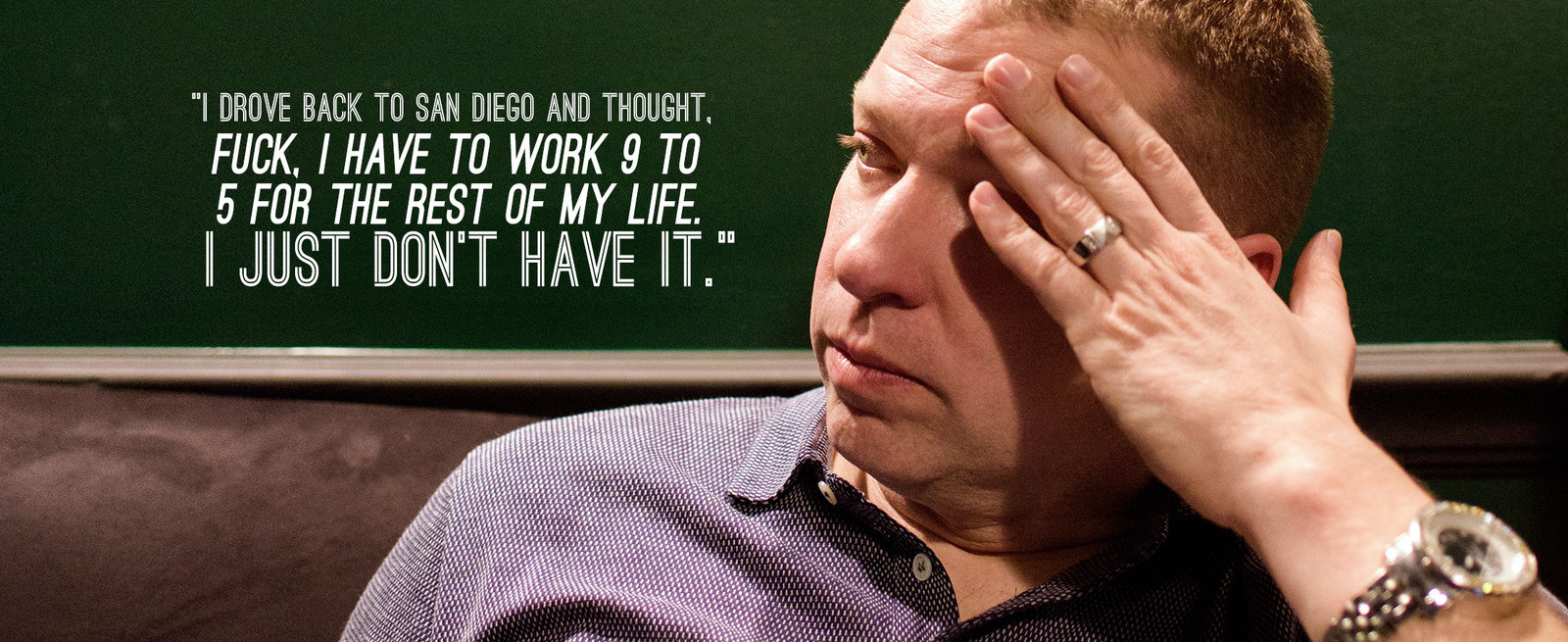

On weekends, Owen started driving up to Los Angeles, where he hoped he might get discovered. The first L.A. club he performed at, in the summer of 1996, was a gay bar called Rage in West Hollywood. “I signed up at 4:00, came back at 9:00, and went ninth out of ten,” Owen said. “It was variety night and the only other comic was blind. I got booed offstage and got a parking ticket. I drove back to San Diego and thought, Fuck, I have to work 9 to 5 for the rest of my life. I just don’t have it.”

Before he left the club, however, a black woman in a blonde wig named DD Rainbow approached him and introduced herself as the MC of an urban comedy night called No Color Lines. She gave him her card and told him he was playing the wrong crowd. “I don’t know what it was,” said Rainbow, who has been part of the L.A. comedy scene for decades and openly wept when told Owen credits her with discovering him. “I just thought he might do better in my room.”

No Color Lines was on Monday nights at the Comedy Store in West Hollywood, and charged comics $5 to perform. Owen's routine didn't change, but the audience did: It was mostly black. “I was shocked when I walked onstage and told the exact same fucking joke and it worked,” Owen said. “And that was when I knew.”

When Owen tours, local newspapers writing up his appearances rarely fail to mention him winning the "Funniest Black Comedian in San Diego” contest in 1996. In fact, Owen said, it wasn’t much of an event. “It was just a radio call-in show,” he said. “I just called in and won.”

By early 1997, he was finding work all over the place, performing at two black comedy clubs in San Diego and driving up the coast to perform in a handful of rooms in Los Angeles almost every night.

Someone passed a videotape of Owen along to Curtis Gadson, then head of programming and operations at BET. He was on the lookout for talent to put on Comic View, a long-running comedy competition show that debuted at nearly the same time as Def Comedy Jam and had already launched the careers of D.L. Hughley and Cedric the Entertainer. Gadson thought Owen was a natural fit and put him on the air that summer. “My dilemma was how much flack I was going to get because he was not African-American,” he said. “And yeah, I got a lot of flack.”

Nobody expected Owen to win, but he did. In January 1998, he got his walking papers from the Navy, moved to Los Angeles, and started hosting Comic View, winning over millions of African-Americans around the country. “I think he did a good job,” Gadson said. “We didn’t lose anything in the ratings.”

One of his first friends in Los Angeles was his eventual roommate, Richard Munns, whom everybody called “Face.” They met through mutual friends, and Munns took Owen under his wing, bringing him to Lakers games, exclusive black nightclubs, and parties hosted by Magic Johnson. Munns called Owen “the first white male friend I’d ever had,” and made it clear that he helped open doors for the young comic.

“Since I was known as a guy you don’t want to cross, I’m sure it helped his transition into ‘black’ entertainment,” wrote Munns in a letter from Folsom Prison, where he is serving 27 years to life for kidnapping and robbery. “There were haters hatin’, and our friendship kept the haters at bay so that G could focus on doing his thang.”

Owen, completely entrenched with black friends, dating black women, and regularly playing black clubs, was having the time of his life. “There was a point where I was too far in and I’d see a white audience and think, Oh, shit, what am I going to do?” he said.

Comic View helped Owen land small parts on television and movies, as well as better-paying comedy jobs. In sleepy Oxford, Ohio, it looked like he had become a star.

Owen calls Think Like a Man, the 2012 film starring Hart, his “Avatar moment.” In it, he plays Bennett, a role that’s been described as the “token white friend” — a middle-class white guy with a white wife whose closest pals all happen to be black. Owen did not appear in the poster or the trailer.

The film was a hit, and in the sequel, Think Like a Man Too, Owen has a larger role with more room to ham it up. When it was released last June, Essence put the whole male cast, and even producer Will Packer, on its cover. But the magazine excluded Owen and the other leading white actor in the film, Jerry Ferrara, causing a minor storm of dissent on Twitter. Nor was he on the DVD cover. ("That was a creative choice I don't agree with," Packer said.)

Owen, however, has made at least an uneasy peace with his perpetual outsider status. “I always say I’m the Karl Malone of comedy," he said. "He was a big black guy who liked trucks in Utah. I am who I am.”

But in Hollywood, Owen's success can be a source of tension. “Some black comics don't like Gary,” said comedian Guy Torry, who met Owen while running an urban comedy night called Phat Tuesdays in Los Angeles in the late 1990s. In part, Torry said, that feeling comes from professional jealousy, but also from a sense of territoriality. “He gets a lot of pushback. A lot of brothers really don't want to see sisters with white guys. They just don't.”

Representatives for Jamie Foxx, Tyler Perry, Hughley, Cedric the Entertainer, Paul Mooney, Hannibal Buress, and more than a half-dozen other prominent black comics all declined or ignored requests for interviews, as did Marc Maron, whose WTF podcast has become a way station for many of the biggest names in comedy, but has never had Owen as a guest.

Eddie Tafoya, who teaches classes on comedy at New Mexico Highlands University, sees a direct line to Owen's humor from Eddie Murphy. "[Murphy] wasn't introspective or confessional, but he was really good at acting out these urban scenes, looking at the situation from the outside in," Tafoya explained. "I think the Murphy school led to the BET style of humor and I see Owen really working with that, the whole fish out of water thing."

By chance, Chris Spencer, the co-creator of The Real Husbands of Hollywood, dropped in to see Owen perform at the DC Improv in December. “A lot of white comedians playing for black audiences self-deprecate without a lot of pride,” said Spencer, who is black. “He doesn’t do that. He talks about black culture. And he does it from a perspective of knowing it and not faking it.” Spencer drew parallels to his own experience growing up in an African-American neighborhood of Los Angeles, where some black kids talked “white” and didn’t fit in. “It’s almost like how some people are born gay,” said Spencer. “Gary was born black.”

For years, Michael Williams ran the Comedy Act Theater out of a nightclub in Los Angeles’ Leimert Park neighborhood, long a cultural hub for the city’s black community. Owen worked the room a number of times when he was just getting his first paid gigs.

“He started getting into the swing of things when there were certain key phrases he'd say that tickled ladies in the audience,” said Williams. “Mainly it was about wanting to have a relationship with a black woman. That’s how he ended up getting so popular.”

Over gargantuan $68 steaks in a crowded downtown Cincinnati restaurant, Kenya Duke told the story of how she and Owen, five years her junior, got together.

Duke is a strikingly attractive, vibrant woman with captivating jet-black eyes. She comes off as a bit shy, and said that when she was younger she would often stand up dates because she didn’t want to leave the house. “Matt Damon tried to date Kenya,” Owen interjected with obvious pride as Duke squirmed and looked down at her filet. “He called her all the time. She might have dated Jason Kidd too.”

Duke grew up in a tough part of East Oakland in a violent era, the daughter, she said, of a political activist who spent time as a Black Panther. She met Owen in 1997 at L.A.’s Comedy Store after a show one night. Not much of a comedy fan, and a single mother of a young boy, she was there at the urging of Shaquille O’Neal, who was at the time her boss at clothing line Twism. “Shaq takes all the credit for us,” moons Duke over the din of the crowded restaurant, where the only other African-American on a Saturday night was fronting the band in the bar, belting out Bill Withers’ “Lovely Day.”

Owen never had a serious girlfriend before Duke, and his devotion to her is obvious. Her number shows up as “Beautiful Owens” on his phone, and when he’s around her, he seems infatuated. She has provided the kind of stable family life he couldn’t imagine growing up. But Duke is also so much more to him.

“I forget she’s black,” Owen said in a red-carpet interview, with Duke by his side, at the BET Awards last June — but in fact he never fails to remind his audiences, bringing her up early and often, sometimes in the first minute onstage.

As Owen worked to build a career, Duke was on the front lines along with him. She got him in with Shaq, who put Owen in his various comedy shows, and introduced him to a wide range of influential black entertainers. When Torry got too busy to manage Phat Tuesdays, she and Owen took it over, running the box office, promotions, scouting, everything, for several years. And when they got married at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in Oakland in 2003, it was as if his passport had been stamped. “I think I may validate him in some way to his audience,” said Duke.

Today, Owen peppers his routine with references to rap music, historically black colleges, Oprah Winfrey, and President Obama. He shuns the slob aesthetic favored by comics such as Louis CK for decidedly more urban attire, and snickers at less-than-pristine sneakers. He drives late-model cars because, he said, his “audience expects it,” and his speech with a microphone in his hand is notably more African-American-sounding than in private. But his all-access, VIP pass straight to the heart of the black audience is always his wife.

“There’s a conception that light skin is more attractive,” Owen said one afternoon as he sprawled on an overstuffed sofa in his basement, half watching late-season football on a giant projection screen. Jerseys signed by famous athletes including Ray Lewis, Chris Paul, and LeBron James lined the walls, and a framed photo of Owen cradled in Shaq’s huge arms sat nearby. “That’s a historical connection: That at some point you have a white ancestor. That at some point the slave master fucked a slave. Well, my wife has dark skin.”

Owen moved the family back to Ohio in 2004, when his career hit a slow patch. Today they live in a sprawling six-bedroom home on a cul-de-sac in a “master planned golf community” in Warren County, a wealthy, homogenous suburb north of Cincinnati. Owen’s stepson Emilio, 19, lives there as well, and his mother-in-law moved from Oakland to be nearby. His son Austin, 14, and daughter Kennedy, 12, attend a private Christian school that Owen calls “very white,” and families of their classmates often come over for cookouts on weekends. The other parents, Owen said, never know who he is.

“I always wonder if my kids will say they’re mixed or black,” he jokes in an elaborate physical routine involving his daughter attending step class and being embarrassed by her father’s race. Hopping around the stage, Owen feigns his daughter’s horror, and is left breathless. “They are never going to say white, that’s for damn sure!”

In January, The Tom Joyner Radio Show started putting Owen on the air every Wednesday morning. “I think our audience thinks about him as a friend or family because he talks about family so much,” Joyner said, noting that his show reaches 8 million listeners a day, 70% of whom are female. “There’s no secret to this. Gary needs to keep serving his base, which is African-American women.”

As Owen relaxed in his basement, watching the Seahawks beat the Cardinals, Duke was upstairs, putting out a spread of barbecued ribs, beans, and cornbread she’d driven more than an hour to pick up. “There’s still people who think me being married to a sista is an act,” Owen laughs. “What, you think I’d make that up for a persona?”

In the Cincinnati steakhouse, decorated in a blindingly overwrought style, with two-tone hardwood floors, red velvet banquettes, massive crystal chandeliers hung under gilded shades, and framed photographs of Frank Sinatra, Owen was all but invisible. The hostess didn’t recognize his name from the reservation. He was just another white customer on a Saturday night.

The night before, Owen performed at the Horseshoe Casino in Hammond, Indiana, with Bruce Bruce, a heavyset comic who grew up in one of Atlanta’s toughest areas and tends to use the n-word at least twice per sentence. Out of 1,900 people in the audience, Owen noted, all but 400 were black. “Even if it’s a white crowd, I tell my jokes for the four black people in the room, not the 100 whites,” he said.

After dinner, Owen headed to the local casino to play blackjack. The valet, who was black, recognized Owen, and smiled. Then the doorman, also black, nodded and shook his hand: “Good to see you, Mr. Owen.” The pit boss, Jennifer, asked if she could take a picture with him. At the table, Owen played aggressively, doubling down often, and refused to look up at the small crowd of people gathering around the table.

“Is that Gary Owen?” wondered Lashae Green, a 23-year-old Cincinnatian who had been playing slots nearby.

“Excuse me, is he Gary Owen?” asked her friend, Stacie Prewitt, 21, who had recently moved from Chicago and said he was the only white comic she liked. A small crowd began to gather. Only when the dealer’s shoe was empty did he turn, stand up, and pose for a few pictures and hugs.

As the valet pulled up, Owen, cracking a wry half-smile, recalled first meeting Kevin Hart in late 1998 while headlining Caroline’s in New York. A mutual friend put Hart on the phone, and the young comic, then unknown, asked Owen if he could have a guest set. Today Hart stars in blockbuster movies, hosts Saturday Night Live, and can’t travel anywhere without being mobbed. "I don’t like to hang with Kevin too much," he said. "Because I want my own entourage." Hart didn’t respond to multiple requests to speak for this story.

“I’m just at the right level of fame right now,” Owen said quietly, pulling out his phone to check his Instagram account, which has 200,000 followers. “People recognize me, but I can lead a normal life too.”

Owen was driving 30 miles from his house to Oxford through a cold drizzle, the scenery outside the Audi shifting from golf courses and McMansions to payday lenders and liquor stores. He was coming home to visit his old high school and congratulate the football team for making the playoffs for the first time in years, a major achievement for a relatively small school in football-mad Ohio. The Bengals game played on the car radio and Owen, a rabid fan, listened intently.

“White comics don’t have to worry about image,” Owen abruptly said during a commercial. “It’s different for me. Where I am, where I come from, I can’t talk about that with my fans.”

Owen frequently jokes about black churches, and how long the services are. The closing sketch to his most recent comedy special is set in a black church where the service turns into a daylong marathon. Owen is often hired by large black congregations around the country to perform, part of a lucrative side business that includes private roasts of college and pro sports teams.

The truth, however, is that Owen doesn’t go to church, and didn’t go as a child. “Black people are Christians, and I have to validate that,” he said. “I have to talk Jesus for them, but I just question a lot. I can’t let my religious beliefs out.”

Owen is an obsessive sports fan and follows his alma mater’s results faithfully, attending at least a game or two every year, despite his heavy touring schedule.

“I tried to get involved in my high school for years, and they didn’t know who I was,” he said over a plate of spaghetti buried underneath chili and shredded cheese at Skyline Chili. “But then they got a new athletic director, a black guy, and he’s been great. Now Talawanda calls me all the time.”

In the school auditorium, Owen, in Air Jordans, jeans, and a T-shirt with an image of a clock that has stacks of cash for each hour on the dial, greeted the team. The racial composition of the Talawanda Braves seemed little changed from the days Owen wore a uniform.

He congratulated them, cracked a few jokes that fizzled, then introduced a short video he produced featuring famous comics — Owen’s friends — offering words of encouragement. The kids tittered at a joke by Faizon Love, and betrayed no recognition at all of Arsenio Hall. There was an isolated giggle or two when Owen clowned on camera with his daughter. The whole team exploded in laughter when Kevin Hart flashed onscreen.

Afterward, Owen walked out of the auditorium, pausing for a moment to chat with the parents of a star athlete. Then he turned and walked out of the school toward his car.

Owen likes to say that all the TV and movie gigs he’s gotten have come directly out of his stand-up. The one role he auditioned for and got, he said, was as a beer-guzzling fraternity brother called Bearcat in the 2008 comedy College, which one critic said “leaves its stain on one’s very humanity.”

He complains that when he reads for what he calls “white” productions, casting directors don’t know who he is and he may as well be at a cattle call. Last year, he read for a part in an upcoming Tina Fey and Amy Poehler movie called Sisters, but John Leguizamo got the role. After another recent audition, he got a callback and found himself up against David Arquette. “#heknewhoiwas,” Owen posted on Instagram.

Veteran comedy writer Robert Peacock was brought on to help Owen sell his sitcom idea. In the show, Owen’s character would be the head groundskeeper for the Cincinnati Reds, which Peacock thought would give it a broad sort of appeal. Peacock, who wrote for The Jeff Foxworthy Show, and who has sold dozens of pilots, said he felt as good about Gary as anything he’d ever pitched, and was particularly excited about the mixed-race concept. All four networks and Comedy Central passed on it. “I choose to believe they're not ready for Gary,” Peacock said. “And maybe a year or two down the line, they will be.”

Will Packer will produce the show if it ever gets picked up. "It would be easier for network executives to 'get' Gary if he were more like a black guy with the swag and had a black feel to him," Packer said. "But he's just a regular white dude who happens to love black culture. He's not easy to put in a box, and this industry is all about putting people in boxes."

Owen also had high hopes for the sitcom and couldn’t hide his disappointment with the networks. “It’s weird to say, but I think they’re kind of racist against me,” Owen said. “I feel like it’s discrimination.”

Gadson, the former BET executive, compared Owen to Jim Carrey, who got his big break on In Living Color, a comedy show emphasizing African-American humor. “Carrey tried a bunch of stuff and continued to grow,” Gadson said. “I don’t think Gary has done that. I'd make him Archie Bunker — a racist. Something that seems impossible to him. That would force him to go to a place in his psyche that’s uncomfortable.”

Owen’s childhood friend, Mike Heineman, remembered him returning to Oxford in 1998 in triumph not long after he hosted Comic View and had started landing TV and movie roles. For his homecoming, Owen played a set at a bar in Oxford's Uptown district. The place was filled with perhaps 150 Talawanda alums, everyone expecting to hear his regular act, or better yet, tales of life on the road and about rubbing shoulders with Shaq.

Instead, Heineman said, it turned into a roast. “He would go around the room and call somebody’s name out and say something insulting,” Heineman remembered. “He just released all of the anger he had throughout the years, on all the people who picked on him in school.” The audience was stunned.

“There are people in Oxford who still bear hard feelings for what he did that night,” said Heineman. “But with Gary, his place in comedy was a culmination of his life. As a kid, he never had anybody who really cared for him, then he tries comedy and starts paying attention to the first audience that paid attention to him.”