When Story Sylwester set up a Facebook group five days after Donald Trump’s inauguration as US president, she didn’t intend to organise a march on parliament, she just knew she had to do something.

This Saturday, 22 April, thanks to the efforts of Sylwester and dozens of other volunteers around the UK, thousands of people are expected to march in London, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Manchester, and Bristol in support of science. They join thousands more scientists at over 400 satellite marches around the world, as well as at the main event in Washington, DC.

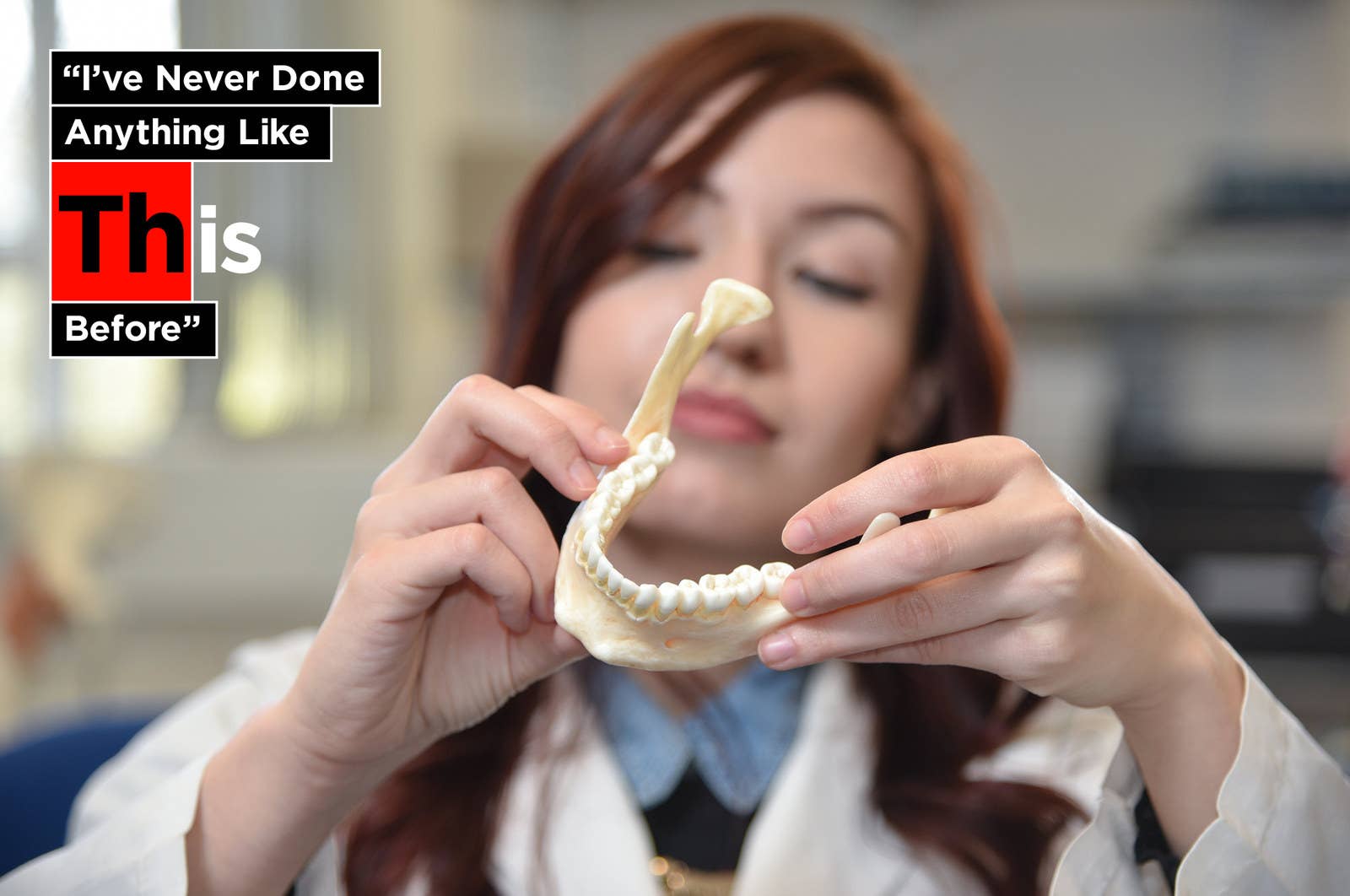

Sylwester is originally from the US and moved to the UK to do an MSc in paleopathology (looking at bones for evidence of disease) at Durham University. Seeing events in the US unfold from across the pond – a short-lived order preventing US Department of Agriculture employees communicating science to the public, for example, or Trump appointing a new head of the US Environmental Protection Agency who’s expressed doubts that humans are causing global warming – she needed to feel like she was taking action, she says.

“I was very excited that a movement for science was happening. It occurred to me that if I wanted to go to a march, then it might be good to just start a group myself,” she tells BuzzFeed News. “I wasn’t intending, originally, to take a role in the planning of our London march.

“I’ve never done anything like this before.”

Since then the movement, in the US at least, has been mired in debate about how organisers have dealt with diversity, or whether it’s too political, and even about whether scientists should be marching at all. Geologist Robert Young argued in an op-ed in the New York Times that “a march by scientists, while well intentioned, will serve only to trivialize and politicize the science we care so much about, turn scientists into another group caught up in the culture wars".

Meanwhile, in the UK, many scientists like Sylwester are picking up placards and getting involved in organising for the first time.

“Scientists are not famous for their camaraderie,” David Reay, professor of carbon management at the University of Edinburgh told the Science Media Centre. “We are trained to question, criticise and, where needed, contest each other’s work. We compete for funding, vie for tenure and race to be first to a new discovery. That we are now marching together is testament to just how threatened our disparate community feels.”

As well as standing in solidarity with fellow scientists in the US and celebrating the positives of science at a time when experts are feeling increasingly ignored, they are highlighting local issues – including how Brexit is affecting their labs and how important science is for the UK economy.

Roberto Cahuantzi, a PhD student at the University of Sheffield, originally from Mexico, is one of them. When he heard about the March for Science movement, he knew he wanted to go to one. But when it looked like nobody else was going to set anything up near him, he did it himself, creating the Facebook group that became the March for Science in Manchester.

“I have been feeling this trend in society about how a lot of politicians are blatantly disregarding the advice of experts. I have felt very impotent in front of these things, like Brexit, the Trump presidency, the problems that Mexican politics has,” he says. “I am trying to feel that I am doing something for a greater good.”

Cahuantzi says climate change is the biggest issue the world is facing right now, and he thinks politicians are ignoring the advice of scientists on it. “I think it’s very, very important for us to speak up, to let them know that we want solutions, real solutions, not procrastination and scapegoating,” he says.

All three members of the team behind the Cardiff march are new to protest organising, too. “I think a lot of scientists aren't normally involved in this kind of activity; it's like there's been a big jump in awareness of the issues around this,” Sarah Jaffa, a PhD student in astrophysics at Cardiff University, told BuzzFeed News.

Jenny Wymant, a cancer researcher, also at Cardiff, says they’ve been getting help from people around the country as they begin to navigate this new sphere.

“It's really nice because that's how science works too,” she says. “If you don't know how to do a thing, you go and find an engineer that does, or you go and find a chemist who can help you make a thing, and the march is like a little reflection of that.”

The last time scientists kicked off in an organised way in the UK was in 2010, when cuts to the science budget were looming and a group of concerned scientists formed the lobby group Science Is Vital. A petition organised by the group drew 35,000 signatures, and 2,000 people went to a rally outside the Treasury to protest against the proposed cuts. They had an impact – the eventual cuts were less severe than what had initially been indicated.

But the March for Science in the UK looks set to be far bigger, with organisers estimating 10,000 people will attend the London march, which starts at the Science Museum and finishes at the houses of parliament.

All of the organisers BuzzFeed News spoke to say that, to some extent, their satellite marches are in solidarity with the March for Science in Washington. But they are also about standing up for local issues, too.

Brexit is one thing that many scientists in the UK want to have a say in. Before the referendum, most wanted to remain in the EU, arguing that it would be better for UK science than leaving. Since then, BuzzFeed News has reported on several scientists leaving the country because of the result, including one EU national who’d applied for permanent residency in the UK and been denied.

Now Article 50 has been triggered, British scientists want to ensure that the government does all it can to soften the blow.

Jaffa cares about Brexit, because her research group contains a lot of EU nationals whose futures are now up in the air. “The government has been not sure what's going to happen to EU nationals living here, which covers about half of the people in my group,” she says. “We need to make sure politicians understand how those decisions could affect science, and make sure the public understands those issues as well.

“One of the things we're planning is a map of where researchers in Wales have lived, where they've come from, whether they were born in Europe or further afield or in the UK, and where they've moved, because a lot of scientists do move around Europe and the world throughout their careers. When the Brexit negations take place science needs to be discussed in that context.”

The importance of international collaboration in science is a point the London marchers want to make, especially in light of the Brexit vote and Trump’s election, according to organiser Vanessa Furey. “We know there's been lots of changes in the last year that have had lots of impact on science,” she says, “and a key concern from the scientific community is the ability to collaborate.”

Last year over 40,000 scientists in the UK signed a petition stating that they wanted to keep access to EU collaborations and projects after Brexit.

Miceala Shocklee, a veterinary student involved in the Edinburgh march, came to the UK from the US and says she felt the impact of Brexit personally while trying to find a project in this country: “When I was talking to professors everyone was very uncertain, because with Brexit they weren't sure about what the structure of their lab was going to be, whether they were going to have to let go of graduate students, and then what their time was going to look like.

“You have all these people who want to go out and discover things and make changes in the world, and they can't because politics is getting in the way of all of that.”

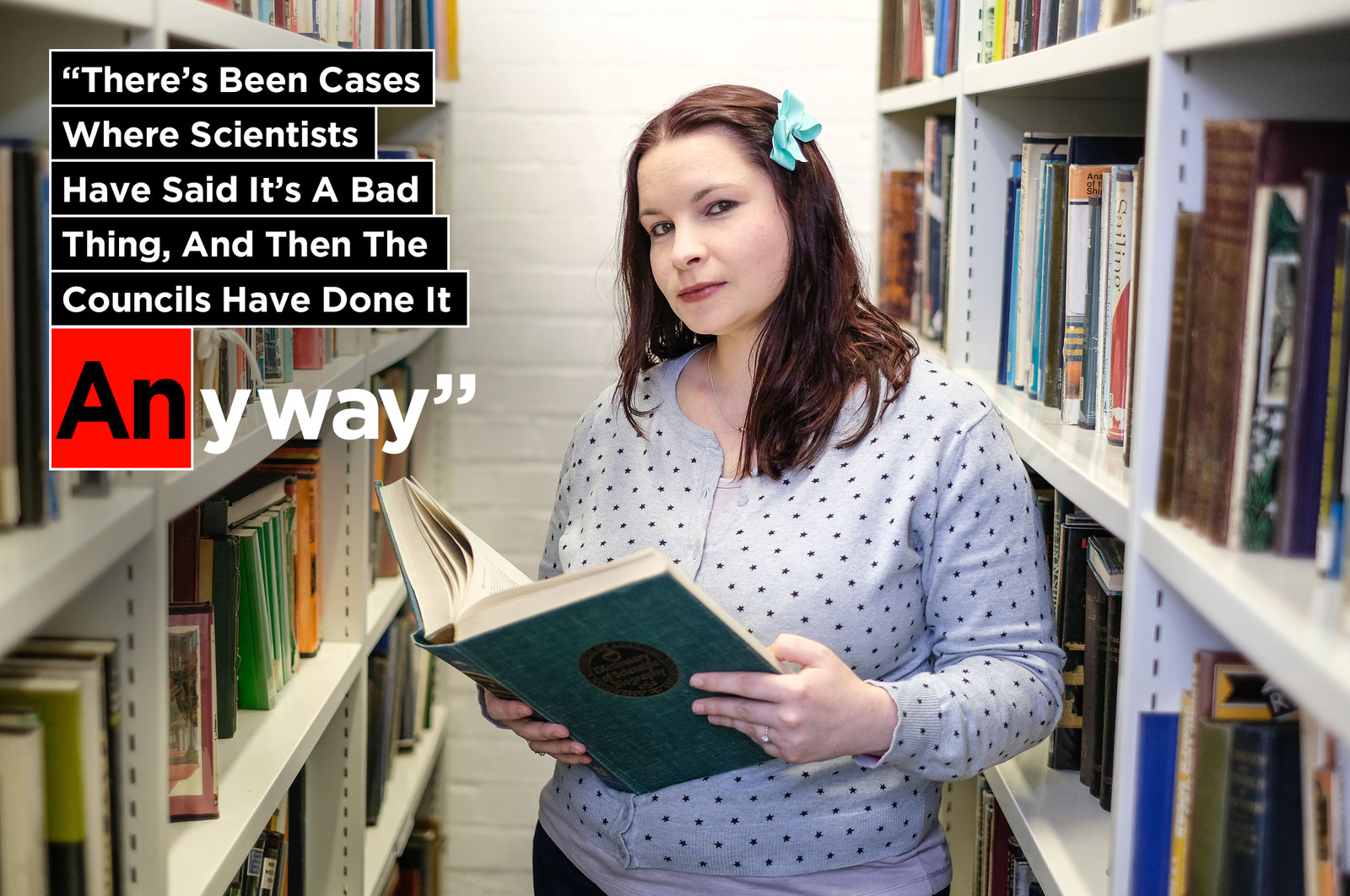

It’s not just Brexit. Pamela Berry, a master’s student in library and information science and organiser of the Manchester march, cited fracking in her area as something that got her fired up.

"In the North West there's been a lot of problems with fracking recently. It's quite a big issue,” says Berry. “There's been cases where people have said 'We don't want this to happen', the scientists have said it's a bad thing, and then they have done it anyway. There's been a lot of distrust."

Last year the government approved fracking at a site in Lancashire after the local council refused permission because of noise and traffic.

And the Cardiff march feels that some Welsh-specific developments aren’t being noticed. In 2012 the Welsh government announced its Sêr Cymru initiative to bring prominent academics to the country and focus on three areas – life sciences and health; low carbon, energy, and environment; and advanced engineering and materials – where it thinks Wales has potential to excel. “Showing how science can help Wales is really important. I didn't know how many science-based companies there were in Wales and how much amazing stuff is going on here, and I think it's not advertised as much as it could be,” says Jaffa.

Of course, being a global movement means that the March for Science has sprawling and sometimes contradictory aims.

“Every single person will have a different answer” to why they’re marching, says Marsha Nicholson, another organiser for the London march, who calls herself a “concerned citizen and science enthusiast”.

And the UK situation isn’t the same as in the US. “In Washington right now scientists and public servants are scrambling to hide data from the administration,” says Nicholson. “That’s very different to the UK government that has committed to supporting scientists with money.”

Robin Cathcart, an environmental scientist involved with the Edinburgh march, who is originally from California, says that although the atmosphere in the UK is “not as openly hostile to evidence and science as a whole” as in the US, “The UK is not putting its money where its mouth is.” She adds: “The UK is lagging behind the rest of the EU, and even the United States, when it comes to science funding."

Last year the UK government announced an extra £2 billion in funding for research and development in the UK by 2020, focused on technology rather than basic, curiosity-driven science. What’s still unclear, though, is whether that money is intended to replace the £1 billion that the UK wins in grants from European programmes each year, which scientists could lose access to after Brexit.

Cathcart compared the evolution of the March for Science to that of the Women’s March that took place in January: “It's alarming when you get a world leader openly saying horrific aggressive things against women, and it's also alarming when you get a world leader openly saying horrific, aggressive things about science and scientists.”

Shocklee, the Edinburgh-based veterinary student, is worried about where scientists stand when it comes to policy-making. "Worldwide right now there's this tension between groups that care about data and evidence-based policy, versus a reaction to that and people who have other values driving what they want to happen,” she says.

And while in the US scientists are arguing about whether marching for science is too political, UK organisers who spoke to BuzzFeed News seem united in their stance: The march is nonpartisan, but you can’t get away from calling it political, because it's calling for politicians to value science.

“It’s wrong to call this march apolitical, because we actually are looking for political change,” says Cahuantzi. He wants politicians to stop “scapegoating immigrants and certain religions” and start focusing on what he sees as the real problems in the world, namely climate change: “My fear is that we are just procrastinating, fighting among each other, and we are not doing something against maybe the biggest threat in human civilisation.”

“The issue here [in the UK] is not to do with any particular political party, but to do with politicians from all backgrounds respecting science and understanding how much science plays into the UK economy and how important that is,” says Jaffa.

Scottish politicians from all parties say they support the march.

Some organisers, however, are reluctant to use the word “protest” to describe what they’re doing. A theme running through all of the UK marches is the celebration of science, and the organisers are keen to project a positive image.

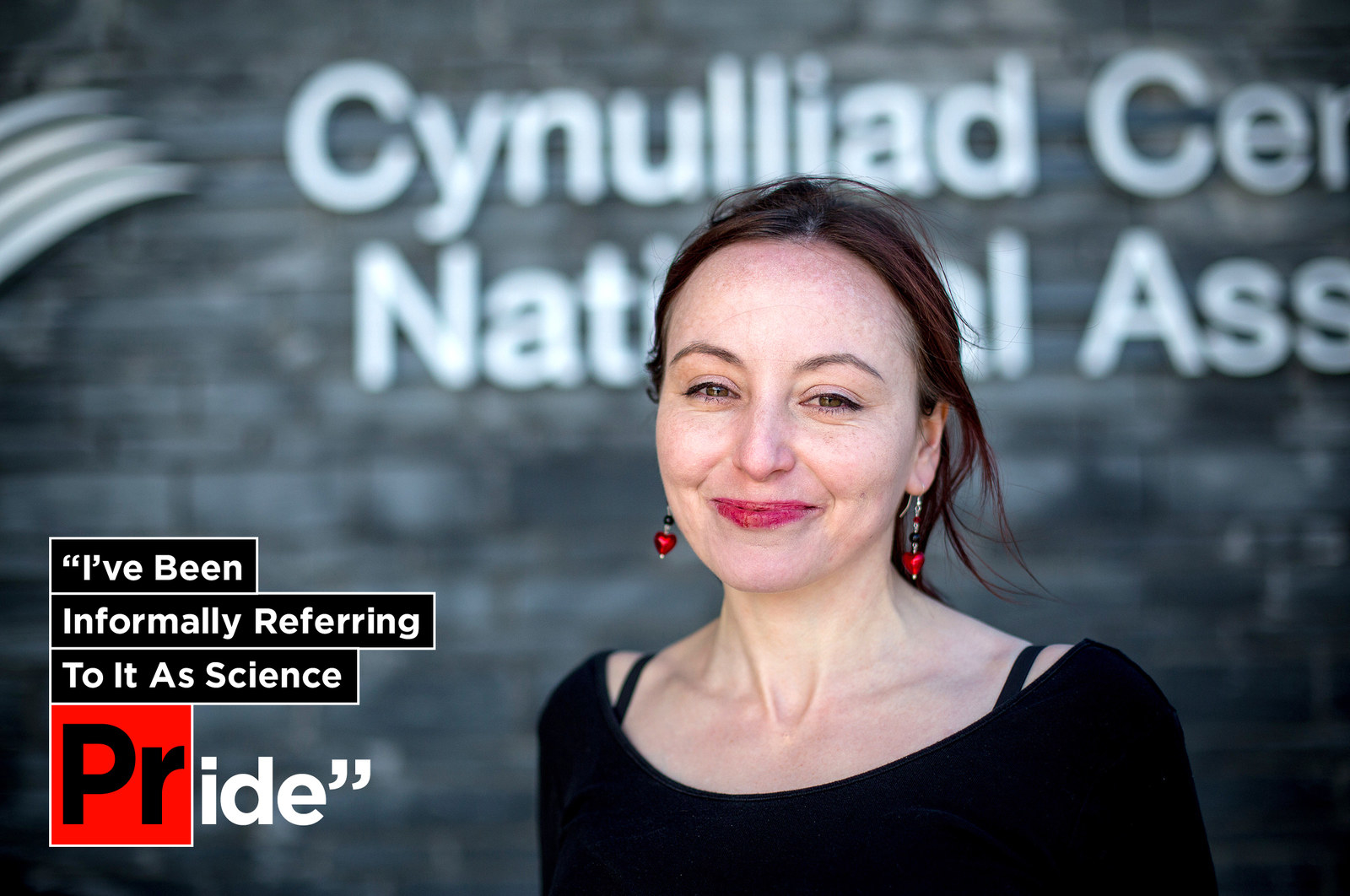

“I've been informally referring to it as Science Pride,” says Wymant. The Cardiff march will involve a fancy dress competition and end at Techniquest, a science discovery centre. The team say they’re hoping it feels more like a family fun day than a protest.

Nicholson, who has spent 20 years managing events for nonprofits, says this is a deliberate choice to make sure people don’t get so downtrodden that they switch off: “It’s very dire, it’s very depressing, it makes you want to disengage – so we want to engage people.”

Dispelling the myth that science is exclusive is also high on the priority list, says Furey. “We know that science can sometimes have an image problem in terms of being seen as stuffy and as the preserve of old white men, and actually it shouldn't be because there are so many brilliant and talented scientists from all backgrounds,” she says.

Sylwester says one her main aims for the London march is just to get people thinking about how science has impacted their lives: “People interact with things that are the results of science all the time – the smartphone in your pocket, you walk through a world of Wi-Fi – and it's great to pay attention to just how large of a role that plays in our lives.”

Cathcart, from the Edinburgh march, agrees. “Science hand-in-hand with government investment is what makes all of our lives tolerable and pleasant. I for one wouldn't want to live in the dark ages, and I'm quite thankful I've got clean water piped into my house, and if my children are ill and I take them to a doctor, everything will still be fine. So science is something that we need; it's the foundation of our developed world. People should hopefully realise that even if they're not involved in science in their day-to-day job, or even if they feel like they're disconnected to it, actually they're not: We're all very much connected to science, and our health and happiness on a daily basis is all due to science.”

“I’m marching because I love science. Science works,” Corinne Le Quéré, director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia, told the Science Media Centre. “With science our life is much more comfortable. With science our choices are far better informed. It is science that supports our peaceful human lives in this complex Earth, and that’s good.”

“The key message is that science is for everybody,” says Shocklee. “Science is a global endeavour. Science impacts people who don't even think about science.”