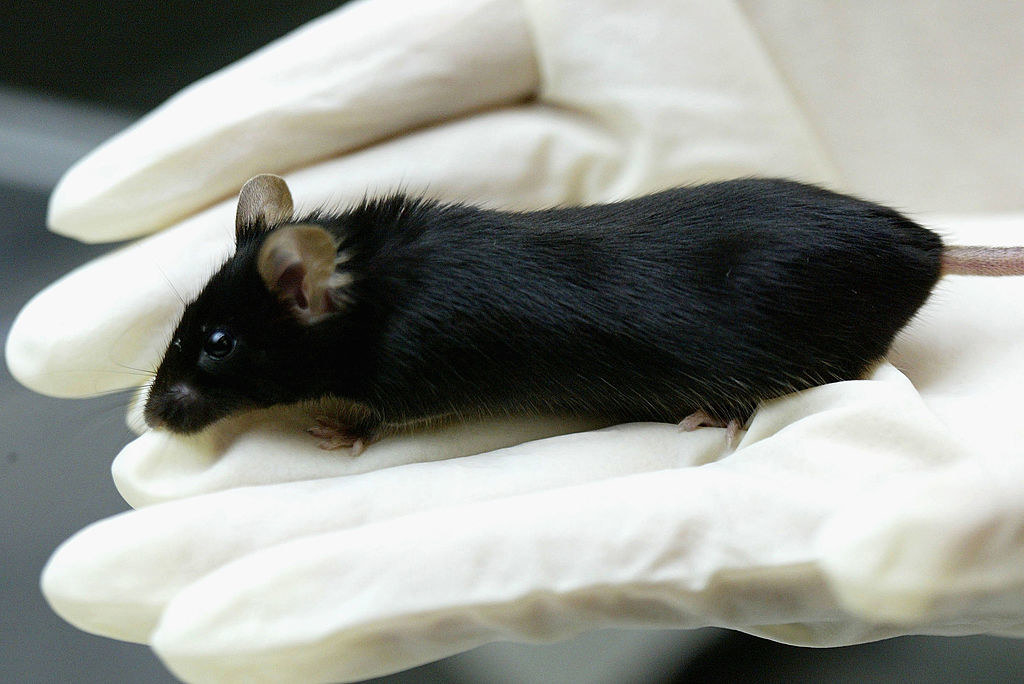

Researchers trying to find treatments for pain should use both female and male mice in their research, says scientist Dr Jeffrey Mogil.

Writing in the journal Nature, Mogil, who runs the pain genetics lab at McGill University in Montreal, says differences in how men and women experience pain and pain relief are "real and robust" and that "we fail in our duties if we conduct research using only male rodents, producing results that might serve only men."

Almost ten million people in Britain suffer pain almost daily, according to the British Pain Society. Research shows that women are more sensitive to and less tolerant of pain than men, and are more likely to suffer from chronic pain.

But new drugs must first be tested in rodents, and researchers are increasingly seeing sex differences in how they respond to pain, too. For example, in 2015, Mogil and colleagues published a study showing that male and female rodents process pain through entirely different immune cells in their spinal cords. Spotting huge differences like that could, eventually, lead to new pain relieving drugs, he told BuzzFeed News.

Despite all of this, too many researchers don't take into account the sex of the mice they conduct research on, or only use male mice, Mogil says.

"If we already know that women are the majority sufferers of a particular disease, and yet we persist in studying them by using male rodents, that just strikes me as ethically indefensible," Mogil says. "Even if you decide you should only be studying one sex, it damn well should be females."

In 2015, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that it would be requiring "the consideration of sex as a biological variable" in research it funds, meaning if NIH-funded researchers choose to use only male mice in an experiment, they must justify that decision scientifically.

The NIH guidelines only officially took effect in 2016, so it's too early to say whether they've been effective at increasing the number of female rodents in experiments.

But Mogil says that researchers he's spoken to are put off using female mice because of a misconception that they introduce more variability, making it harder to draw conclusions from the data. "The problem is that while that's a perfectly reasonable expectation, it has been proven to be empirically false," he told BuzzFeed News.

He also believes that some researchers think the NIH requirement means they have to double the number of mice they use in experiments. But he says that doesn't necessarily have to be the case. "You don't need to use any more mice than you would have before, you just need to make half of them male, half of them female," he added. "That way you'll see big sex differences and miss small ones. It's no more money at all, and we're finding something instead of nothing."

Dr Vicky Robinson, chief executive of the UK's National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs), says that there are no plans to introduce specific requirements for using both male and female rodents in publicly-funded experiments in the UK, but that NC3R's ARRIVE guidelines (originally published in 2010) already state that the sex of animals should be reported when researchers publish their findings in scientific journals.

"Gender as well as strain, age and so on can have an impact on scientific outcomes and how they are interpreted," she told BuzzFeed News in a statement. "What is important is reporting what sex animals are used and why they were selected (i.e. the biological basis for using that sex)."

A spokesperson for the Medical Research Council told BuzzFeed News that they endorse the ARRIVE guidelines, as well as the Experimental Design Assistant, also created by NC3Rs, which is an online tool to help researchers design robust animal experiments.

Mogil says that scientists should think of the bigger picture and not lose sight of their obligations to society when designing their experiments. "The message to my fellow pain researchers is: start including female mice and rats in all your experiments today," he writes. "You have nothing to lose, and both men and women with pain have everything to gain."