The crowds that gathered on January 21, 2017, looked like something out of a movie: a more subdued Zion rave from The Matrix Reloaded or a District 11 revolt straight out of Panem in The Hunger Games. The worldwide Women’s Marches didn’t mandate any sort of dress code, but there seemed to be a silently agreed-upon color scheme: pink everything. Pink pussyhats, pink scarves protecting against the snow in Utah, pink tanktops to welcome the sun in Los Angeles; aerial views of the demonstrations revealed seas of pink only briefly punctured by the more muted shades of the color spectrum.

The pink was a uniform of sorts, a bold visual message to a new political regime — just in case the pink Sharpie signs weren’t message enough. Marchers gathered to protest (among other things) women’s legal control over their bodies; the election of a dynastic businessman whose popularity grew out of reality TV stardom; and a pandemic scale of sexual harassment and assault. The Women’s Marches, like any good resistance movement — fictional or real — had a costume, a unifying look, a literal common thread. In this instance, the halting pop of modern pink.

Costume designers are always aware of the importance of optics, but never more than now, when women’s bodies are increasingly politicized. We can imagine a buffet of end-times scenarios, so stories about a teenage girl leading a nationwide revolution or a post-apocalyptic generation of women who are valued solely on their ability to reproduce don't seem so far-fetched. These waters appear familiar because we’ve watched them play out from a safe distance through a screen — in The Hunger Games and The Handmaid’s Tale, respectively — but navigating them ourselves is entirely new. As reality and fiction uncomfortably blur, it’s natural to turn to some of our most beloved onscreen heroes for solace and, perhaps, guidance. BuzzFeed News spoke with the women who designed and dressed our heroes not only to endure the end of the world, but also to survive it.

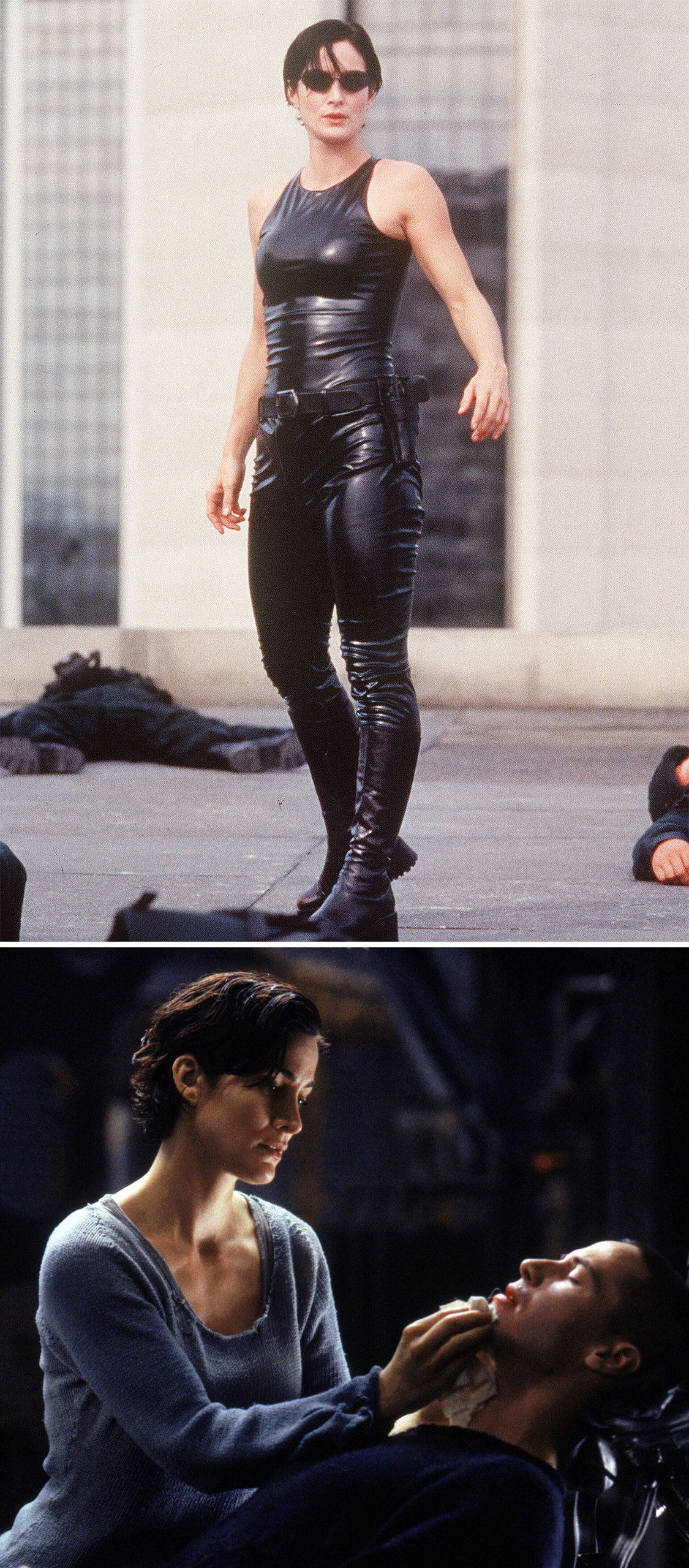

The Synthetic Woman: The Matrix and Jupiter Ascending, designed by Kym Barrett

Kym Barrett, a frequent collaborator of the Wachowskis, is the costume designer behind the now-classic looks from the siblings’ Matrix Trilogy and Jupiter Ascending. The Matrix is a mainstay in modern dystopian film, but costuming for women has changed quite a lot since Carrie-Anne Moss first donned that black leather jumpsuit back in 1999 — and almost entirely for the better, according to Barrett.

In the early ‘90s, there were even fewer women in mainstream action movies for designers to dress. “Now it’s really kind of the standard,” Barrett told BuzzFeed News. “Now, some heroines might dress more like a man and act more like a man. ... Now, most women are written much more like they really are.”

In Barrett’s designs for the dystopic women of the The Matrix Trilogy — Trinity (Moss) and Niobe (Jada Pinkett-Smith) — there’s a metaphorical tug-of-war between the natural and feminine versus the synthetic and masculine. She’d juxtapose the cozy earthtone sweaters and exposed collarbones of the clothing aboard the Nebuchadnezzar and the modest homes of Zion against the leather, reflective sunglasses, and gaudy metals that converge over flesh like armor inside the Matrix. Barrett wanted to play with the idea of double identities. “What you saw was not necessarily what was underneath,” she recalled. Inside the simulated world of the Matrix, Trinity and Niobe were “encased in a kind of protective shell, which extends from the reflection in the fabrics to the reflection in the sunglasses, shields so that people could not see through to the real humanity.” But in the real world, the characters are often swathed in "very organic and woven and light” clothing, with their necks and chests visible and vulnerable.

Barrett admits she struggled more while creating the design for the Wachowskis’ 2015 film Jupiter Ascending, mostly with creating a new world in space while still keeping the environment grounded. “I tried to capitalize on the idea of precious metals and precious stones that were not necessarily earthly,” she said. In Jupiter, there’s a more political bent to the clothing design, especially in Jupiter’s (Mila Kunis) wedding dress. The wedding itself is a false political alliance orchestrated by Jupiter’s betrothed and kinda-sorta genetic son, Titus Abrasax (Douglas Booth), whose family “harvests” entire planets of people. Marrying Jupiter is Titus’s attempt to try to steal Jupiter’s legal inheritance: Earth.

Jupiter’s wedding dress, an elaborate floor-length gown of delicate silver cloth and garish jewels — which alternate between blood-red and opalescent — is awash in nature imagery. Her headpiece, heavy and harshly twisted into her hair, showcases metal cherry blossom branches and jewel-encrusted blooms — all glittering reminders of nature inverted. “There was imagery from Earth that they brought into their world and used, not because they love cherry blossoms flowering, but because it was a conceit and a trick, and a way of getting the public’s attention,” Barrett clarified. “I love that idea where you take away everything and then give it back in a kind of nasty way. Oh here are some birds and flowers, but you can’t have them. It’s a nasty reminder of what you’ve left behind.”

Jupiter ends up saving the world and returns to her humble life as a cleaning lady, quietly and benevolently taking on the role of Earth's legal owner. That form of leadership, both feminine and understated, may seem foreign to our planet at present. Barrett, too, sees the stark contrast — and she thinks clothing can continue to play a role in the resistance to malevolent overlords, whether machine or man. “I feel like we need to rebel, you know?” she said. “I want us to kind of reflect all the good things and all the cultures from the countries where immigrants are coming from: India, Pakistan, Africa, take their prints and their colors and kind of use them as a protest for something good.”

The Relatable Teen Revolutionary: The Hunger Games, designed by Judianna Makovsky

Judianna Makovsky is no stranger to making the fantastical look relatable: Her design credits include Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone; both Captain America: The Winter Soldier and Captain America: Civil War; Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2; and the upcoming Avengers: Infinity War. But there was something different about designing the costumes for 2012’s Hunger Games, something decidedly more familiar than past projects. “One of the things that’s more frightening about science fiction and dystopian worlds is if they’re recognizable,” Makovsky said. “I wanted whatever the clothes were for the women to be recognizable; everything is more frightening when it’s real.”

Makovsky said that, in designing the costumes for the film, the book’s detailed descriptions came in handy. “When I read it, it really came off as being incredibly American; a combination of Depression-era clothes and modern workwear.” Of all 13 districts in Panem, Makovksy was most excited to design the clothing of Katniss's impoverished home, District 12. The former mining town, reminiscent of present-day Appalachia, is all but forgotten. While the opulent districts closer to the Capitol indulge in futuristic finery, the ultimate goal in District 12 is simple: Don't starve to death. The coal-dusted denim, plain canvas, and knitted gray wool layers of District 12 stand in direct opposition to the flashy metallic cloth and painstakingly stitched sequins of the Capitol; this is class war, down to the final thread.

As relatable as District 12 may read in print, other descriptions in the book tend toward the more fantastical. People in the books literally have their skin dyed blue, Makovsky laughed. She and director Gary Ross had a fear that following the book’s flamboyant clothing details to a tee — especially for Effie Trinket and other Capitol dwellers — would overshadow the core anti-establishment message of the story (though Effie’s outfits were, Makovksy admits, the most fun to design). “Gary and I kept saying we know it reads well, but it couldn’t be that scary if it’s alien. We were so worried we would get people who looked like Star Trek [characters] — which is wonderful for Star Trek! But doesn’t work [for Hunger Games], which is really political.”

Instead, Makovsky actively worked to downplay the books’ ornate costume descriptions and keep the looks in the film rooted in reality — especially when it came to Katniss’s most notable costumes. “In the later Hunger Games [movies], the clothes become the focal point, but when you’re setting up a movie, the characters should be the focal point. It’s a compliment, often, to a costume designer that people don’t notice the clothes. It means the character is successful.”

The subtle (and literal) dressing down took painstaking work. Makovsky custom-designed, built, and aged Katniss’s hunting jacket after it became apparent that building an oversized jacket like it was in the book proved to be too physically restrictive: Actor Jennifer Lawrence couldn’t fire an arrow when wearing it. Effie Trinket’s fuschia Reaping dress was originally green, as described in the book, but Makovsky redesigned the puffy-sleeved, two-piece suit when green proved “not strong enough, not jarring enough” next to the faded colors of District 12.

Makovsky also pared down Katniss’s famous fire dress. “In the book, [the dress] is described much more elaborately. We could have gone in that direction, but in a way, you would have been looking a the dress and not at the transformation of the girl.” Makovsky’s main influence when designing the fire dress, which she agrees “looks a little high school prom-ish,” was Natalie Wood’s blue dress in 1962’s Gypsy. “It is the most simple dress ever; it’s a blue satin dress, there’s nothing on it; it’s form-fitting and gorgeous. And suddenly, you see Natalie Wood as this beautiful woman,” she said with a sigh. “I think you really saw Jennifer [Lawrence] have a similar transformation there.”

The film premiered five years ago, which seems like a lifetime ago in light of the current news cycle, but ultimately, Makovsky thinks the film holds up; if she were dressing Katniss today, her look — only slightly futuristic, but above all, relatable — would be more or less the same. After all, what scares Makovsky isn’t dystopia itself, but the normalizing of it. “Right now, for me personally, I think what’s going on out there is terrifying,” she said, referring to the current state of political affairs. “It’s seemingly normal to people, in a strange way. I think that’s what makes successful dystopian design in films more relevant. There are a lot of future dystopian films that I think are gorgeous, and I love the clothes, but I find the more frightening ones are the ones you’re living.”

The Modern Political Prisoner: The Handmaid’s Tale, designed by Ane Crabtree

Ane Crabtree, whose résumé is peppered with television costume design credits from the Sopranos pilot to Masters of Sex, knows how terrifyingly real her work on The Handmaid’s Tale feels right now. Based on Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel and set in Gilead, a present-day dystopian version of the United States, the Hulu show portrays a world in which women have no say over their own bodies and are valued (or devalued) on their fertility. It’s a warning, an uncomfortably prescient one, and it’s supposed to scare you.

“I tried to create something for absolutely right now: 2016 and 2017. It is absolutely today; stripped of their rights, stripped of choices they get to make as women,” Crabtree told BuzzFeed News of the titular characters. “All of that is infused in the story.”

The show was still filming in Toronto during the 2016 US presidential election in November, an event that creatively fueled Crabtree’s work. “There was nothing like being out of the country when all this political chaos and political dystopia went down,” she said. “It was a blessing and a curse to be away, because you could throw all that stuff, that anxiety and pathos, into the work creatively.”

Crabtree drew inspiration from 1900s fashion in addition to the descriptions from Atwood’s novel, and was very careful to avoid a more modern “body-con, sexualized Kardashian look.” Every aspect of the handmaids’ hyperconservative outfits were designed with one theme in mind: control. The layered look is a practical combination of pieces that Crabtree designed less as a costume and more a package that prison guards could easily hand out to inmates. As the democratic United States ended and the totalitarian republic of Gilead began, Handmaids were issued a thick red cloak draped over a conservative red dress, utilitarian brown pants buttoned over high-waisted white cotton underwear and thick brown socks, and a rigid, winged bonnet hiding the hair. The white cotton underwear was “meant to make them look like little girls,” Crabtree said. “So down to the underwear, it’s a way to control them, and a way to control their minds.”

Even the seemingly benign brown boot covers that peek out as Offred (Elisabeth Moss) and Ofglen (Alexis Bledel) walk by the river together serve as a dark reminder of their lack of agency. “The covers were a means to underline the idea that these are prison uniforms,” Crabtree said. “We’ve taken away their shoelaces so they can't hang themselves.” Crabtree wants the audience to imagine themselves literally in those shoes. “I don’t want folks to watch it and not feel like it could be them. I want you to watch it and feel like, For God’s sake, this could happen to me. It could happen to my mother, the lady down the street that used to run the laundromat.”

No matter how close it seems we skim to a real-life Gilead, Crabtree chooses not to entirely buy into doom and gloom. “If you’re feeling burdened by the weight of what’s happening in the world around us, the only way out is to scream via your creativity. Whether you’re a writer, painter, filmmaker, costume designer, dancer. Or else...” she paused. “Or else you’re going to go crazy and acquiesce to what’s happening in society. And you should never do that.” ●