MEXICO CITY — It’s easy to see the world as fracturing: the “America First” policies of US President Donald Trump, Brexit, the rise of the National Front in France, the authoritarianism of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

But not Latin America, and certainly not Mexico, the country serving as Trump’s main punching bag.

While Trump argues about how his neighbor will pay for the wall, Mexico is looking at an opportunity that was unthinkable just weeks ago: finding a new set of allies by making a U-turn and heading south. Bucking a global trend toward insularity, countries in Latin America are strengthening alliances among themselves, regional commissions are gaining traction, and one president has even called for the creation of a joint South American citizenship.

“In the north, walls that divide and separate are erected, while in the south, its roads that integrate and unite,” Bolivian President Evo Morales said on Twitter. Morales urged Mexicans to build unity based on a Latin American identity as tension between Trump and his Mexican counterpart reached a boiling point last week.

The buds of renewed integration across Latin America are far from the global vision of Stephen K. Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist. In 2014, he predicted that “center-right revolt is really a global revolt. I think you’re going to see it in Latin America” among other places, he said. But Bannon’s brand of nationalism — exclusive and sealed by impenetrable barriers — is unlike the one that has spread south of the US, which is steeped in references to people from the region as “brothers” and supporters.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto recently said that he will deepen the country’s relationships with Argentina and Brazil, and promised to strengthen its presence in Central America. The love is mutual: as Trump intensified his hostility toward Peña Nieto, the presidents of Colombia and Peru pledged their support to Mexico while Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro warned, “Whoever picks on Mexicans, is picking on Venezuelans.”

Despite the complexities of the region, with left-wing populist leaders holding on to power despite eroding approval ratings, and a handful of pro-business presidents settling in across their borders, the diplomatic overtures have come from across the political spectrum.

During a recent meeting of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, or CELAC, a regional bloc created in 2011, Morales asked Mexico to rejoin the Group of 77 and China, made up of emerging nations with a powerful godfather.

Invito a México retornar al G77 y juntos fortalezcamos CELAC. Unidos seremos la potencia que en su diversidad const… https://t.co/wIbchhnKd2

This is not to deny the shadow cast over the continent by the US, which remains the pre-eminent partner of Mexico. Such is its influence that despite a bitter and public altercation with Trump and reports that Trump threatened military force against Mexico, Peña Nieto has agreed to continue negotiations after canceling an official meeting.

Over the past century, there has been no closer relationship in the Americas than that of the US and Mexico. The destinies of both countries appear irrevocably intertwined in matters of security, trade, and culture. It’s not just the $583 billion that were traded in goods and services in 2015; daily life criss-crosses the border as if it were one big neighborhood. An average of 70,000 vehicles and 20,000 pedestrians cross from Tijuana to San Diego every day, for example; 10K races have been weaving between Ciudad Juarez and El Paso for two years now.

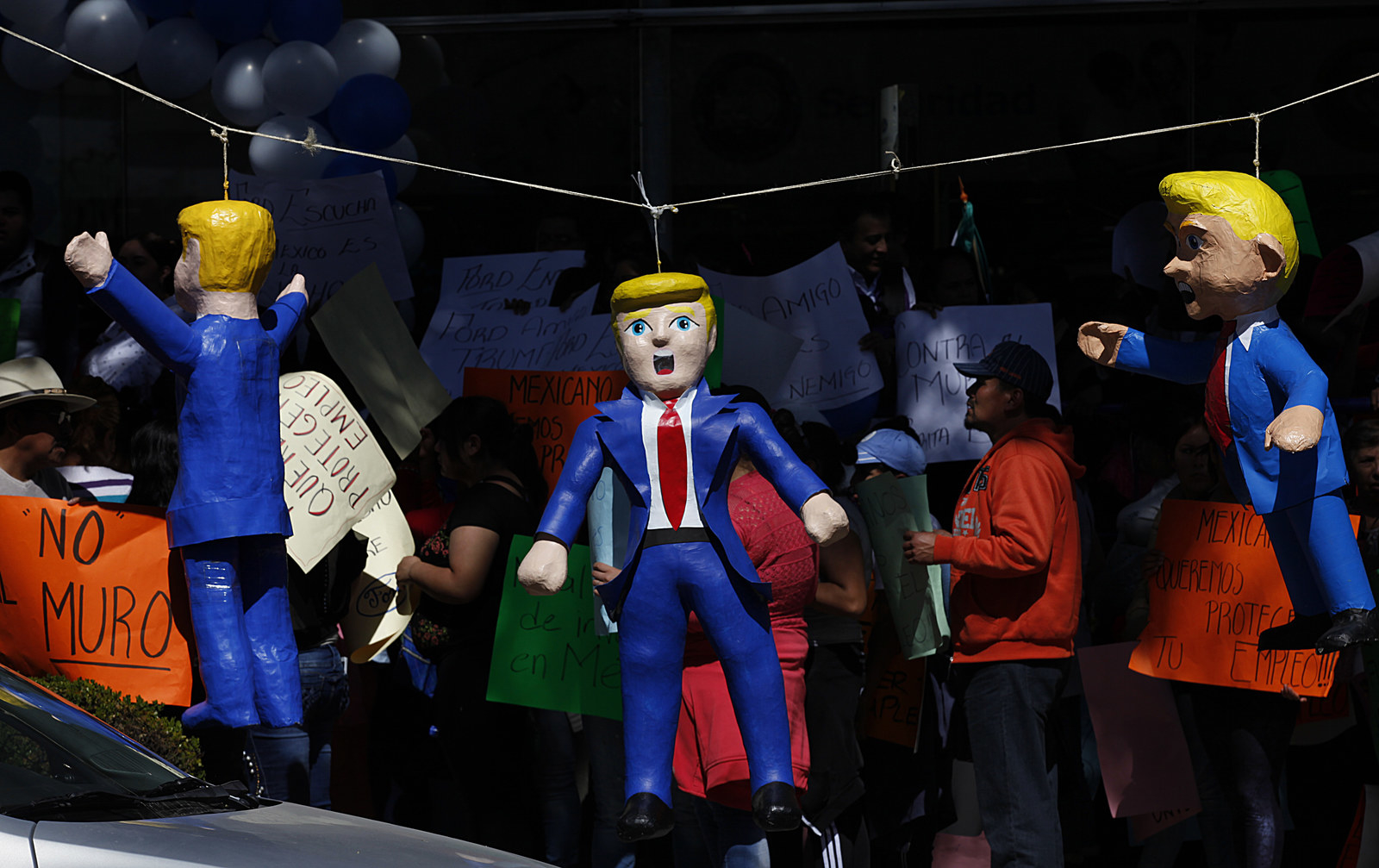

It is no surprise, therefore, that when Trump said Mexico was sending its worst across the border, Mexicans were incensed. The repudiation trickled down the continent. “Mexico is from Mexico all the way down,” said Eunice Rendon, an immigration expert and former head of the Mexicans Abroad Institute, echoing a feeling in the region that when Trump says Mexico he means all of Latin America.

After Trump signed an executive order in his first week to implement his plan to separate the two countries with concrete — a backtracking of decades-long efforts to bridge the gap between the two — the pressure on Mexico to begin shifting its gaze elsewhere grew.

Glimpses of a shift are already evident. Mexico’s Economy Minister Ildefonso Guajardo said the country is willing to walk away from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) if it does not benefit from the renegotiation Trump is demanding.

Latin America is an obvious choice for partnerships in the era of Trump, not only because of language and geography but also the strong anti-American sentiment there. Many of the region’s nationalist leaders have united their supporters under an anti-Yankee banner, often blaming the US for their economic problems.

If Mexico turns toward Latin America and the Caribbean, it will tap into a region of 632 million people spread across 42 countries with a total GDP of $5.2 trillion. At least 65 trade agreements have been signed across South American countries. The Pacific Alliance, made up of Mexico, Chile, Colombia, and Peru — and which Argentina’s President Mauricio Macri has expressed interest in joining — is well-positioned to fill in the gap of a receding US.

(Trump recently withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which several South American countries have signed up to join, and is threatening to do the same with NAFTA.)

For the first time in nearly four years, Peña Nieto may have the public support needed to make a drastic change. After he canceled his scheduled meeting with Trump, many Mexicans appeared to back the president, whose approval ratings sunk to near single-digits in December because of a series of corruption scandals, rising crime rate, a battered economy, and, in August, a controversial invitation to then-candidate Trump to come to Mexico.

“There is a moment of empathy now and, in diplomatic terms, he can use it to build alliances,” said Rendon. Peña Nieto’s relief at the subtle change of heart, at home and abroad, is evident. “As President and as a Mexican, I’m moved by the support our country has received,” he said on Monday.

But it isn’t clear if Peña Nieto is ready to fully commit to making the leap south.

He did not give a reason for canceling his attendance at the CELAC meeting — a mistake, according to Juan Cruz Olmeda, an international relations expert at the Colegio de Mexico. “Mexico should have been there to send a message,” said Olmeda.

Peña Nieto does not appear to have plans to visit his Latin American counterparts, nor has he sent high-level teams to the region to engage with government or business groups in recent weeks. His office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

On Tuesday, the president of Unasur, a group of Latin American countries, called for “collective solidarity” among its members. But promises of a united front echoed across the region remain, for now, merely symbolic.

Engaging with Latin America, ready as it may seem to welcome Mexico, will be a complex challenge for Peña Nieto. The region has been weakened by deep political divisions between left-wing nationalist leaders in Ecuador, Bolivia, and Nicaragua and pro-business right-wing governments, such as the ones in Brazil and Argentina. Members of Mercosur, an important regional bloc, expelled Venezuela last year for failing to comply with the group’s democratic principles. Venezuela called it a coup d’etat.

And tensions may begin to rise, regardless of the anti-Trump unity flowing through the hemisphere. Last month, Argentina’s President Macri modified the immigration code to speed up deportations of, and ban entry to, foreigners with criminal records, a move feared by neighboring countries with flagging economies.

Still, Trump’s aggressive policy toward Mexico may be the unifying agent Latin America needs to put the region’s unity before individual differences. While many leaders in the region voiced their support for Hillary Clinton during the campaign, Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa recalled that the region came together in repudiation of George W. Bush’s “primary, elemental” policies far more than it did under Barack Obama.

Latin America “would be better off with Trump,” Correa said plainly.