HAVANA — Every couple of months panic hits newsrooms around the world as Fidel Castro’s death is announced on Twitter. A scramble ensues as reporters try to confirm the rumor and editors make sure his obituary is up to date. Moments later, calm is restored as it turns out a fake account was responsible.

But there is one newspaper where the staff remains permanently unruffled. At Granma, the official newspaper of Cuba’s Communist Party, there is no Wi-Fi, leaving most of its reporters offline as soon as they step away from their desks, so Twitterstorms tend to pass them by. The paper’s deputy editor, Oscar Sanchez Serra, carries around a beaten-up old Nokia phone; he has no need for a smartphone to keep up with breaking news — after all, Cuba remains mostly cut off from the internet.

On the plus side, he said, given their close ties to the state, the editors of Granma are likely to know before anyone else when Castro does eventually die. “There is no doubt that we will be the first to find out,” said Sanchez.

Now, more than five decades after revolution swept Castro to power, Granma — and the rest of the island — is facing a huge test. Today, around 5% of Cuba’s 11 million inhabitants have internet access, but that looks set to change. This month, 35 Wi-Fi hotspots opened across the island. Some say this gives hope that the Communist country, subject to decades of disastrous economic policy compounded by a punishing U.S. embargo, is inching its way toward a more open society. After Barack Obama announced a sweeping shift in Cuba policy in December, the White House said boosting internet access would be a priority for his government. For its part, the Cuban government said earlier this year that it "wanted to make the internet available to all," according to Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, the country's first vice-president, and seen by some as the most likely successor to the Castros.

Inevitably the changes are happening slowly and — for now, at least — Granma’s newsroom remains trapped in a time capsule. Its offices stand just off Revolutionary Plaza, a grassy square in Havana’s busy Vedado neighborhood under the perpetual watch of Camilo Cienfuegos and Ernesto “Che” Guevara, whose silhouettes are etched into the buildings lining the square.

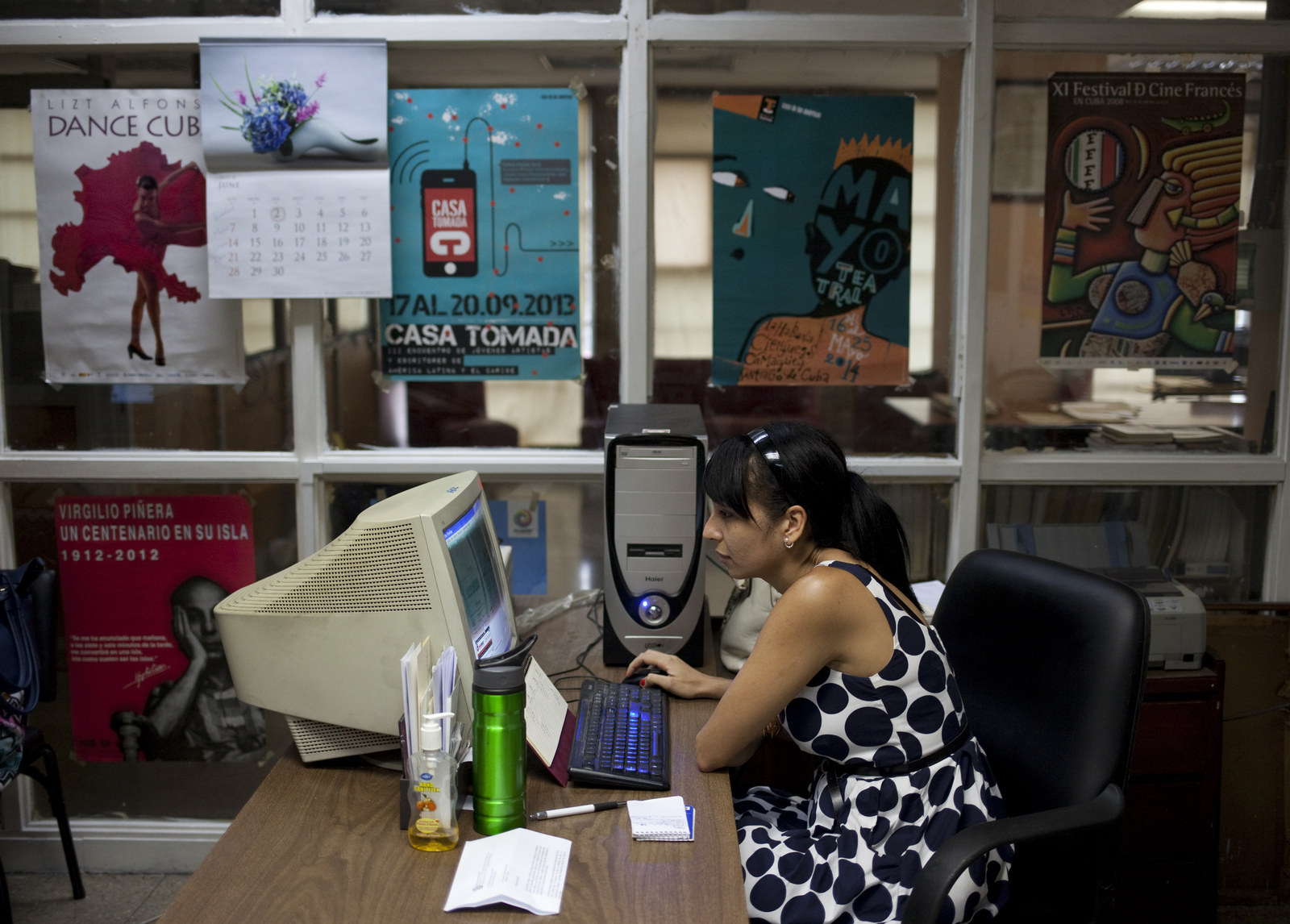

Inside, the office is peppered with decade-old beige LG computer monitors and large-button telephones installed in 1998. There are no standing desks or ergonomic office chairs here — and while most newsrooms are littered with newspapers and magazines from around the world, at Granma there’s nothing more than a pile of copies of a Cuban weekly. In a country where censorship is everywhere, Granma’s inspiration, and competition, is Granma.

Now the paper, like much of the island, is trying to enter the 21st century. Its website, launched in 1997 and getting about a quarter of a million unique visitors a month, mostly from abroad, is set for a revamp. They’re looking to redesign the physical paper too, making photos bigger, with plans to start running them in color. Its foreign editor, Sergio Alejandro Gomez, said the goal is: “web first, print second.”

But the paper, like Cuba’s leadership, will need to confront a question that has plagued oppressive regimes the world over — how can it embrace the openness of the internet while also pleasing ruthless censors?

Sanchez was unequivocal: “The internet will not change the editorial line ... I’m the one the party put here.” Granma, he said, would never criticize the revolution’s leaders and always runs stories about sensitive subjects by the Communist Party before publishing them.

The consequences of that censorship have been profound for reporters in Cuba, including some that worked at Granma. The paper's former international news editor, Aida Calviac Mora, left Cuba for Miami last year, telling America TeVe that new ideas were viewed as threatening and that there was a crisis of credibility in Cuba between readers and the media. In 2011, the journalist Jose Antonio Torres was arrested and sentenced to 14 years in prison on suspicion of espionage for writing a letter to an employee of the U.S. Special Interests Section, according to local reports.

It is difficult to gauge how much support the leadership has in Cuba since many people are afraid to express negative opinions and face repercussions when they do. According to a poll published by the Washington Post and Univision in April, 53% of those surveyed said they were dissatisfied with the political system in Cuba, 58% said they had a negative view of the Communist Party, and 75% admitted to being careful when expressing their opinions in public.

Dissidents are frequently arrested; on Tuesday, the U.S. State Department voiced concern about the detention of approximately 100 peaceful activists in Cuba this week. According to Freedom House, a Washington-based nonprofit, Cuba is the most restrictive country in the Americas in terms of press freedom and free speech. Reporters Without Borders ranked Cuba 169 out of 180 countries in its 2015 World Press Freedom Index.

As a result, many Cubans take Granma with a pinch of salt even though it’s the country’s highest-circulation newspaper, with half a million copies printed each day. It has a staff of around 280 people, and just one foreign correspondent based — almost inevitably — in Venezuela, with whom Cuba has close economic and political ties.

With little internet access on the island, many of Granma.cu readers come from abroad, and in particular via social media. Around 80% of traffic to its website, which totaled 274,554 unique visits in May, according to an internal report provided by Sánchez, comes from Facebook and Twitter.

In an effort to keep up to speed with the changes anticipated on the island, Granma's bosses plan to launch a web-based TV channel, audio, and interactive graphics in the near future. When the foreign editor heard that BuzzFeed was visiting the offices, he smiled broadly. “Twenty things you didn’t know about Granma! The first of these? That the director of international news at Granma is 27 years old,” said Sanchez. He’s not the only one: 60% of the paper’s reporters are “very young,” and of these, “many are under 30,” he added, reflective of Cuba’s younger generation, which is desperate to get on the web themselves.

Relics from the past can be seen everywhere in Granma’s HQ, especially on the picture desk, where dusty bronze photojournalism awards from the 1970s are neatly arranged in a filing cabinet. A dozen vintage cameras, including a folding one from the 1930s, lay on a simple table, giving the place the feeling of a museum.

Fortunately these are just for display. Photographers use semi-professional Nikon cameras for assignments, said Juvenal Balan, head of the photo desk, which is not ideal but allows his team to meet the paper’s expectations. Still, “there is a lag in technology,” he said, a thick copy of the Yellow Pages laying next to his computer.

The faces of Camilo Cienfuegos and Ernesto "Che" Guevara adorn Revolutionary Square. A previous version of this story said it was Guevara and Fidel Castro.