Hi! If you care about tech, it probably feels like you've been overhearing a lot of annoying conversations lately. Conversations about valuations, price-earnings ratios, seed stages. Conversations constructed entirely of words that regular people don't use. Conversations about bubbles.

All this talk makes the situation sound more complicated than it is. Allow me to answer a few of your questions.

What's a bubble?

When things that are really worth very little are treated as though they are worth a lot.

Are we in a bubble?

I'm not, but maybe you are? Viddy, the utterly uninteresting "Instagram for video" that's apparently being valued at $350 million for no other reason than someone calling it "Instagram for video" in exactly the right coffee shop at exactly the right time, is in a bubble.

Facebook, a company that makes money and is in a position to buy companies like Viddy, is not in a bubble. Venture capitalists are in the bubble only if they say they aren't.

The accusatory "we" phrasing of the bubble question might have something to do with why nobody can seem to give it a straight answer, and why otherwise rational people are writing things that are baldy fallacious, or intentionally omitting. Nobody wants to admit to being part of a bubble. It's like asking people if they're hipsters.

So there is a bubble?

Yes.

How do you know?

Because companies that make no money are being given lots of money for reasons that make no sense to normal people. This is not inherently bad or wrong — there are ways a company can be valuable in the long term beyond making money right now — but when this happens a lot and very suddenly, it means there's a bubble. When Evernote gets valued at a billion dollars, it's a bubble. When failed startups get picked up for tens of millions of dollars, it's a bubble. Basically, when strange and inexplicable things start happening every day, it's a bubble.

But isn't that what investing in a new business is all about? Guessing that one day it'll make money, even if now it doesn't?

Yeah.

So why is this different?

Because that's not what's happening here. In most situations, you invest in a new business to help it grow, then eventually to reap the rewards of your early support when the business becomes successful. What's happening a lot in Silicon Valley is that people are investing not because companies need funding to accomplish something, but because they fit the profile of a company that might get purchased by a larger company that has cash to burn. A lot of these companies appear have no plans to ever make money. This is some seriously abstract capitalism.

Every investment is in part a bet; healthy venture capital investment is largely a bet; bubble investments are only bets.

Is this like the last tech bubble?

Nahhhhh. This one is relatively contained within the investment and VC world; the 90s dot-com bubble was big enough that it started to entrap the general public. It's kind of funny how things have become inverted: the first bubble was built around a bunch of products that nobody used but that everyone was investing in; this one is about products that lots of people use but only a handful of people can invest in. In that way, this bubble's fundamentals are a little bit stronger. Sort of.

Also, though this may be the hindsight speaking, the last bubble was an order of magnitude more ridiculous. Basically every startup you hear about today was pitched back then, too, when they were far less plausible. Online TV before broadband. Stupid stuff like that.

Seriously, watch these ads. They aired during the Super Bowl for god's sake.

So this bubble isn't a big deal?

It is — just not as big as the last one. In fact, the last bubble wasn't even as big as the last bubble. Its pop was undeniably dramatic to those involved and certainly devastating to people whose retirement portfolios had been steered toward risky tech stocks, but its economic effect on the general public was exacerbated by outside factors. The September 11th attacks, specifically.

Are you invested in any startups? No? Then chill. If/when the bubble pops, the stocks of large tech companies like Google and Apple and (soon) Facebook will take a hit, but these are generally healthy companies and they'll be fine. They're like Amazon was in 2000, more or less. It'll be painful for the tech industry and for some connected industries — Dave Winer points to higher education — but unless regular people start getting entangled, it won't be a dot-com-level disaster.

That said there's no guarantee that regular people won't get entangled.

Why not?

The Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, or JOBS Act, will soon let regular people invest in startups. Not like lose-your-house money, but still: dollars people need. This, I think, is one of the strongest parallels this bubble has to the dot-com bubble: then, for a few years, everyone with an E-Trade account fancied himself a day-trader; soon, every Techcrunch commenter with a Hedgeable account is going to feel like he could be the next Marc Andreessen.

This is dangerous. At least with publicly traded companies you have access to a certain amount of information about what they do, how they spend their money and how healthy they are. Startups are more opaque.

So, when's this baby gonna pop?

Probably when something else bad happens. Dunno, let's say a major country in Europe defaults on its debt? A meteor? If it simply continues as is and gets too big, it'll leak more than it'll pop. If something comes along and disturbs it, it might explode. It's possible that this one will end in such a gradual way that the die-hards will never have to admit that it was a bubble.

Who's the Pets.com of this bubble?

Hard to tell yet. Maybe Color — that was fucking nuts. But Instagram's cool. They make something useful and great and got bought by a company that has revenue, so it's not gonna be them.

It's likely, though, that we haven't met our poster boy yet. Check back with me when Pinterest goes public, or when Facebook acquires the word "pivot" for a trillion dollars.

The thing I'll probably associate most strongly with this bubble is the rise of the conflicted press. The departure of the staff of the most important startup blog to start another startup blog, this time openly funded by the venture capital firms the blog intended to cover, is and always will seem like surrealist performance art. Yes, everyone is conflicted somehow, but that doesn't mean you should try to be as conflicted as possible.

So what am I supposed to do?

Don't buy into it too much. I understand why venture capitalists are as enthusiastic as they are, because they're in a position to make lots of money and there are a lot of new companies right now that are doing really important stuff. I understand why the press indulges them to an extent, because a bubble creates a million interesting business stories. These people have a vested interest in this bubble, so they'll perpetuate it.

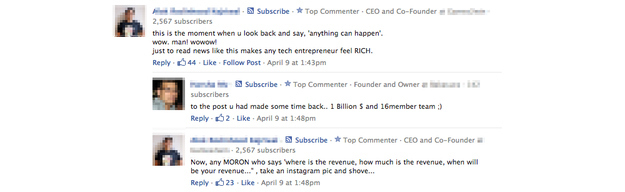

What I don't understand is the roving band of internet acolytes — this frothy mass of commenters and Twitter gurus and third-tier "cofounders" who buy into this stuff more fully than anyone who's truly involved. They comment on every acquisition story with a "congrats! great job! sick exit!" and celebrate rounds of funding either like the births of friends' children or with a vengeful "I told you so" zeal. They seem to subscribe to the notion that all startup activity is inherently good. They're true believers, and they help amplify this stuff to the outside world, where it can grow into a bigger problem — they're like dedicated hype men for a rapper that doesn't really believe his own lyrics.

So that's what you can do. Not be one of them.