As American medical marijuana researchers sit in legal limbo, unsure of what the Trump administration will do next, Canadian researchers are showing huge progress in figuring out medical uses for pot.

The study, conducted by the National Research Council, shows some pretty interesting results in pot’s therapeutic benefits, and sets up an effective new way to test the potential benefits of marijuana.

The research council, which acts as the scientific arm of the Canadian government, was testing how well two main compounds in marijuana work in treating pain: Tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC; and Cannabidiol, or CBD.

The results tended to show what a lot of other research shows: Both THC and CBD can be useful in treating pain.

To that end, the report isn’t earth-shattering. It is, however, the sort of work that adds to the body of scientific research necessary to figure out how medical marijuana should be used, dosed, prescribed, and advertised. Canada, which has had a fully regulated medical marijuana system for more than 15 years, has been at the forefront of that kind of research.

America, not so much. Since 2014, Congress has had to pass amendments preventing the Department of Justice from going after states with legal medical marijuana programs. That could soon change. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has pressed Congress to allow that amendment to expire. Many states with medical or recreational marijuana systems in place worry that Washington could try and seize their marijuana, even if it is intended for scientific research.

That puts the state programs, may of which are still getting on their feet, in a precarious spot.

Meanwhile, in Canada, it’s the federal government that is doing the research.

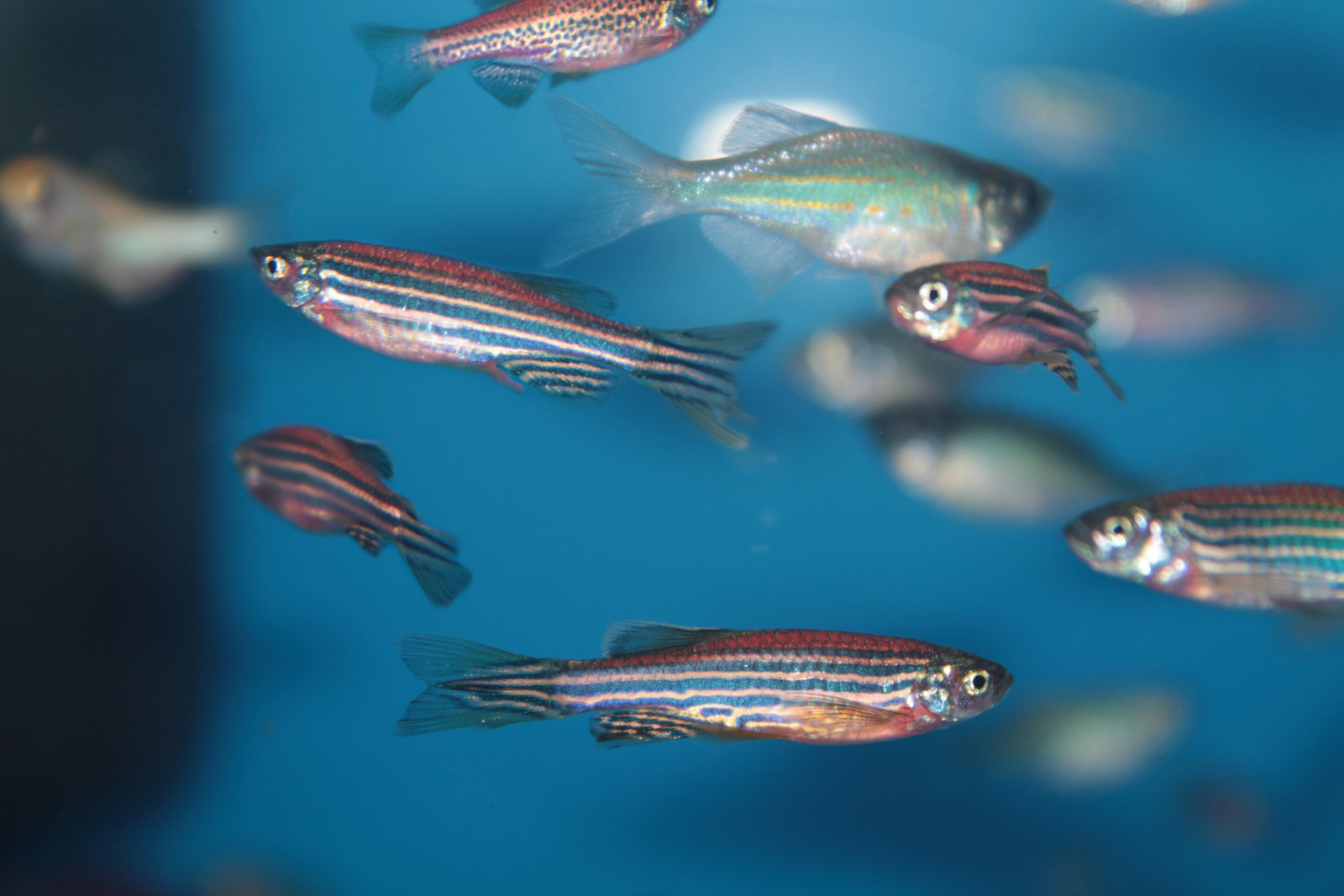

In the September study, published in the peer-reviewed Behavioural Brain Research journal, the researchers were looking for something very specific. They were looking for how the drugs impacted the patient (in this case, zebrafish larvae.) For comparison, they used ibuprofen, the main ingredient in Advil, and acetaminophen, which is in Tylenol.

The results showed that while all four appeared to be useful in treating pain, two came with side-effects: THC, it seemed, affected the baseline behaviour of the larvae. In other words, they either got sleepy or high. The same happened, to a different degree, with acetaminophen. Ibuprofen was neutral.

It was CBD that stuck out. Of all four, CBD had the lowest impact on the larvae’s normal behaviour. In fact, CBD helped the larvae recover faster from the initial shock of the pain.

This is pretty much in line with several other peer-reviewed studies from the past decade. A 2007 study-of-studies found CBD and THC useful for treating multiple sclerosis pain. A 2008 study in the Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management journal found CBD effective in dealing with hard-to-treat pain. A 2011 study in the British Journal of Pharmacology found CBD to be a “useful therapeutic agent” in treating pain in rats.

In this Canadian study, researchers were careful not to make any broad claims, but the results definitely suggest that marijuana with the right amount of CBD could even help patients recover from the pain faster, instead of just dulling the pain itself, without any major side effects.

But while improving, or even replacing, traditional painkillers would be a big step forward for medical marijuana research, many in the industry are really hoping that it could become a replacement for highly-addictive, and even deadly, opioids.

“That would be optimal,” says Dr. Lee Ellis, one of the researchers on the study. He cautioned that this study is just a “starting point” but added: “That’s where this could go.”

But while Ellis’ research is just joining a building field of study on marijuana’s potential benefits for pain relief, the really interesting change is how he got the result.

Zebrafish, tropical freshwater fish that are painfully common in pet shops, are used in many research labs (although Ellis’ lab is the only government lab doing this work in Canada.) Zebrafish are often a first step before scientists step up to rodents, mammals, and then humans.

By testing their larvae, however, scientists can test a wider variety of drugs much faster. Ellis says it could allow researchers to develop a kind of “mix-and-match” system for THC, CBD, and more familiar chemicals, and to anticipate the benefits and side-effects in the early stages.

And while those two are the most advertised parts of marijuana, there are hundreds of other active components that are less understood and may also carry therapeutic benefits.

Right now, figuring out the health benefits, or drawbacks, of marijuana strains with different mixtures of CBD and THC is based on clinical trials in humans mixed with a healthy dose of guesswork.

This sort of more rigorous research is actually putting the science into the medical marijuana industry.

In the absence of that real research, cannabis companies have made dubious claims about the drug’s ability to treat cancer and a range of other illnesses.