For most of history, clothing sizes weren't standardized at all. That's because most clothing was made at home, by hand, or by personal tailors. Most women had ONE dress (unless they were super rich or famous or something.)

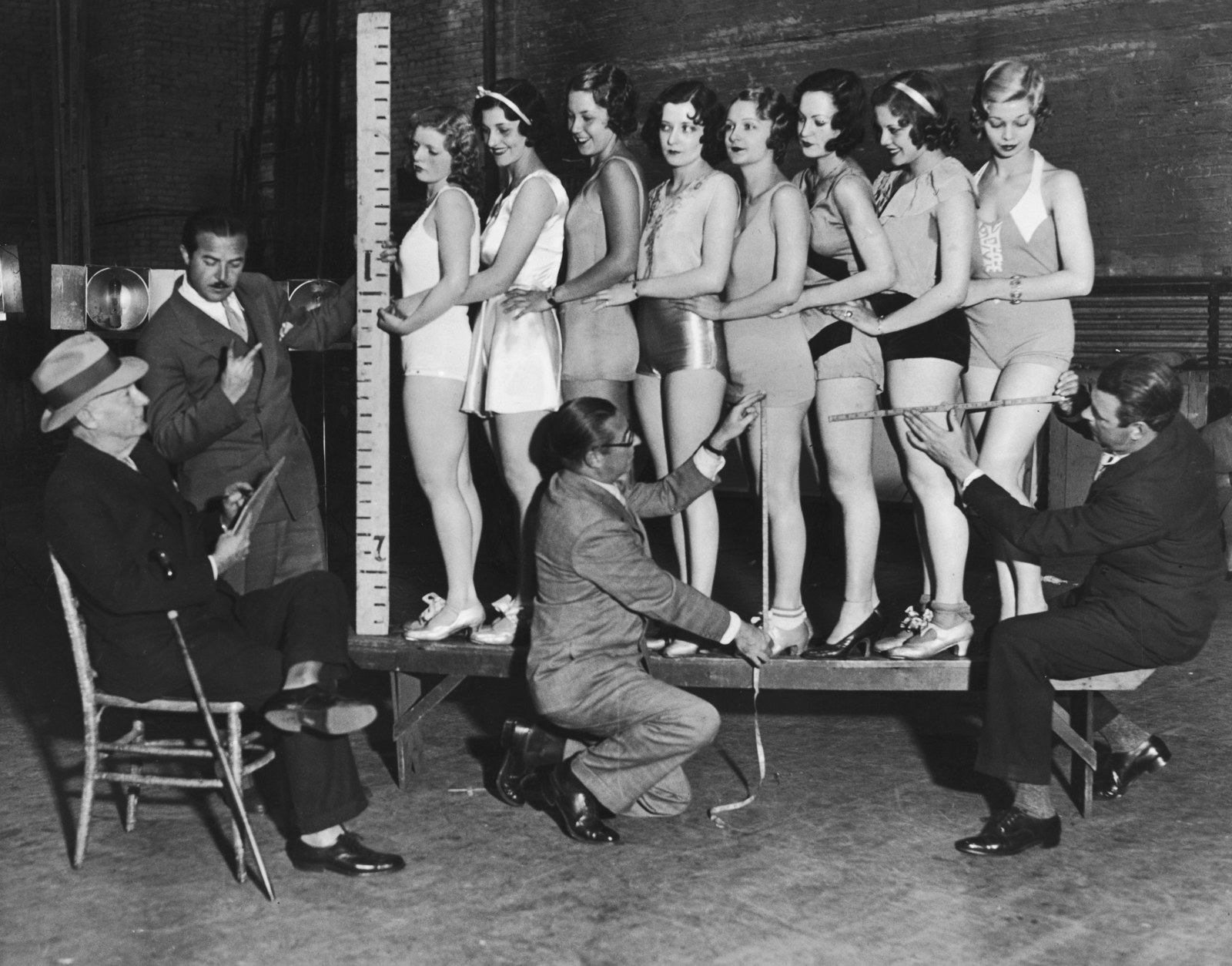

But after World War I, manufacturers began looking for cheap ways to make clothes for lots of people without having to tailor-make every single garment. At first, girls were sized by age. So a girl who was 16 would wear a size 16, and a girl who was 12 would wear a size 12, etc, etc. Women’s dresses were sized by bust size. Not surprisingly, this proved immensely problematic because chest measurements were kind of unreliable, right?

Manufacturers quickly realized that the process needed to be streamlined to save time and money — the lack of standardization was estimated to cost clothing manufacturers around $10 million a year. Enter the US Department of Agriculture.

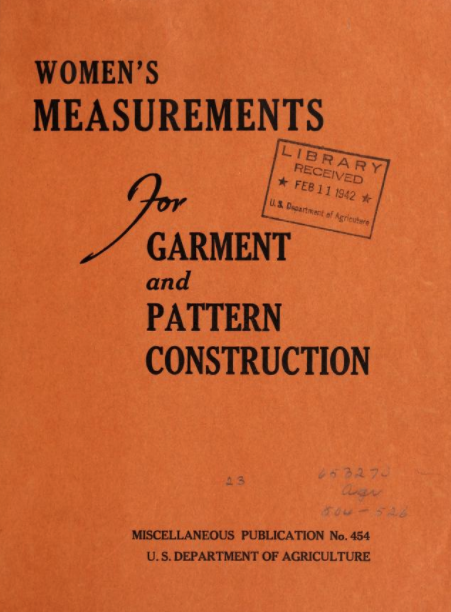

Sure, it sounds kind of bizarre, but the USDA was a big part of clothing history. In 1939, the USDA, under the post-Depression Works Progress Administration, launched a study called Women’s Measurements for Garment and Pattern Construction, with the aim of coming up with a uniform measurement and approach to clothing construction. The project was actually undertaken by the USDA's Bureau of Home Economics, a now-abandoned government bureau that studied "the best ways to clean, sew, and purchase food and clothing." The bureau measured nearly 15,000 women in seven states, and collected 58 separate measurements from each woman — including a measurement for something called “elbow girth.” What even.

Of course, there were some problems with the depth and breadth of their study. For one, the study only measured white women who came from a similar low-income socioeconomic background. And because of prevalent fashion (and diet) trends at the time, the majority of the women surveyed happened to have an hourglass shape. Still, the bureau felt it had collected enough data to make standardized sizing recommendations.

They eventually pared the 58 individual measurements down to five specific ones: weight, height, chest, waist, and hip. Weight, mercifully, was thrown out, and for several years those measurements dictated manufacturing standards in clothing factories. Clothing patterns were built with those four specific measurements in mind.

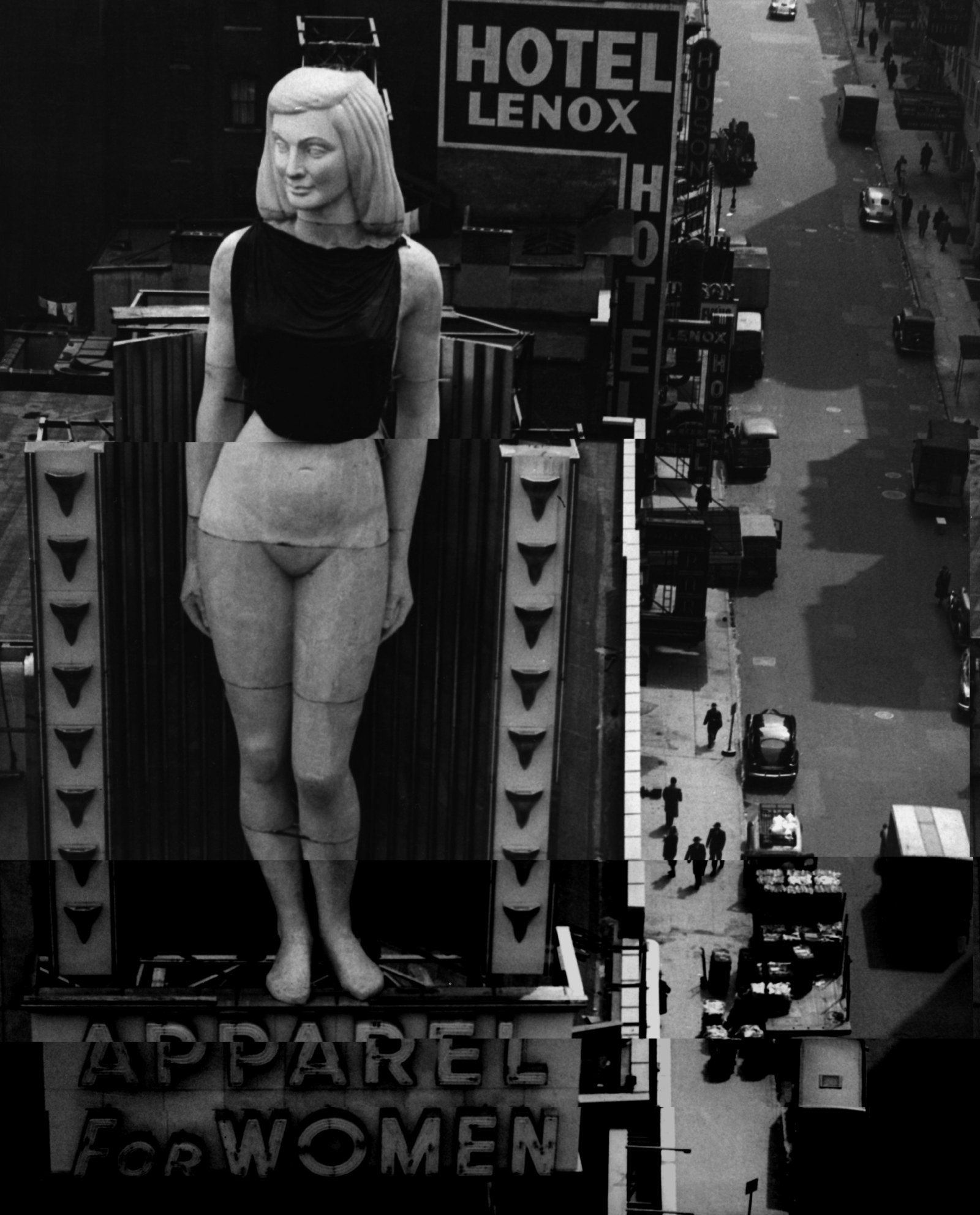

Then in the late '40s, the National Bureau of Standards reassessed their original data pool and realized that it may have been a bit, oh, narrow. They added a bunch of female military officers to the pool, but they were also white and super slim. In 1958 they released a revised Body Measurements For the Sizing of Women’s Patterns and Apparel, a comprehensive guide that advocated for women’s clothing to come in sizes ranging between 8 and 42, and be available in tall, regular, and short heights, and plus and minus indications for weight. (So yes, as you’ve heard a zillion times before, Marilyn Monroe was a size 12 in the ’60s, but that’s because the sizing in the ’60s started from 8, not 0.) The new size guide became the standard-bearer by which clothing was made, measured, manufactured and marketed. It also became a potent way for women to begin assessing their own size and shape in relation to each other. Not surprisingly, dieting culture and the marketing of diet foods and weight loss plans became a big business in the 1960s. Womp womp.

The guide was revised once more in 1970 and manufacturer participation in the program became voluntary. And then in 1983 the standards were thrown out completely. And that’s when things got real wild.

Of course, most manufacturers stayed roughly aligned to the pre-existing standards in order to make it easier for their customers to find stuff that fit. But in many cases, sizing became dependent on the measurements of a brand’s particular series of fit models. And just as many brands began preying on the egos of their consumers by using vanity sizing to sell goods.

What’s vanity sizing? It’s the premise that people will be more prone to purchase a garment if the size on the label is smaller. It’s why you might be a size 12 in one store but a size 6 in another. It's become increasingly popular in the last 20 or 30 years, as Americans have gotten collectively bigger while the fashion industry continues to privilege small, skinny bodies. Stores know that people are way more likely to buy something if their serotonin is flowing and their self-esteem is up. Shopping is an emotional thing, after all. Admit it, vanity sizing has probably made you inordinately happy or insanely frustrated at least once, right?

So what’s the solution to sizing woes? If the last hundred years of women’s clothing struggles have taught us anything, it’s perhaps to realize just how arbitrary the number on the tag really is. Sizes have changed, but so have bodies — and why wouldn't they? Our lifestyles have shifted radically in the last hundred years and those changes are naturally going to be reflected by new body shapes. By adhering to a sizing system that was set up nearly a hundred years ago for bodies that served drastically different functions, we're just setting ourselves up for failure. Buy and wear clothes that you like and that fit you the way you want, and realize that sizing — the way we’ve been doing it, anyway — ain't nothing but a number.