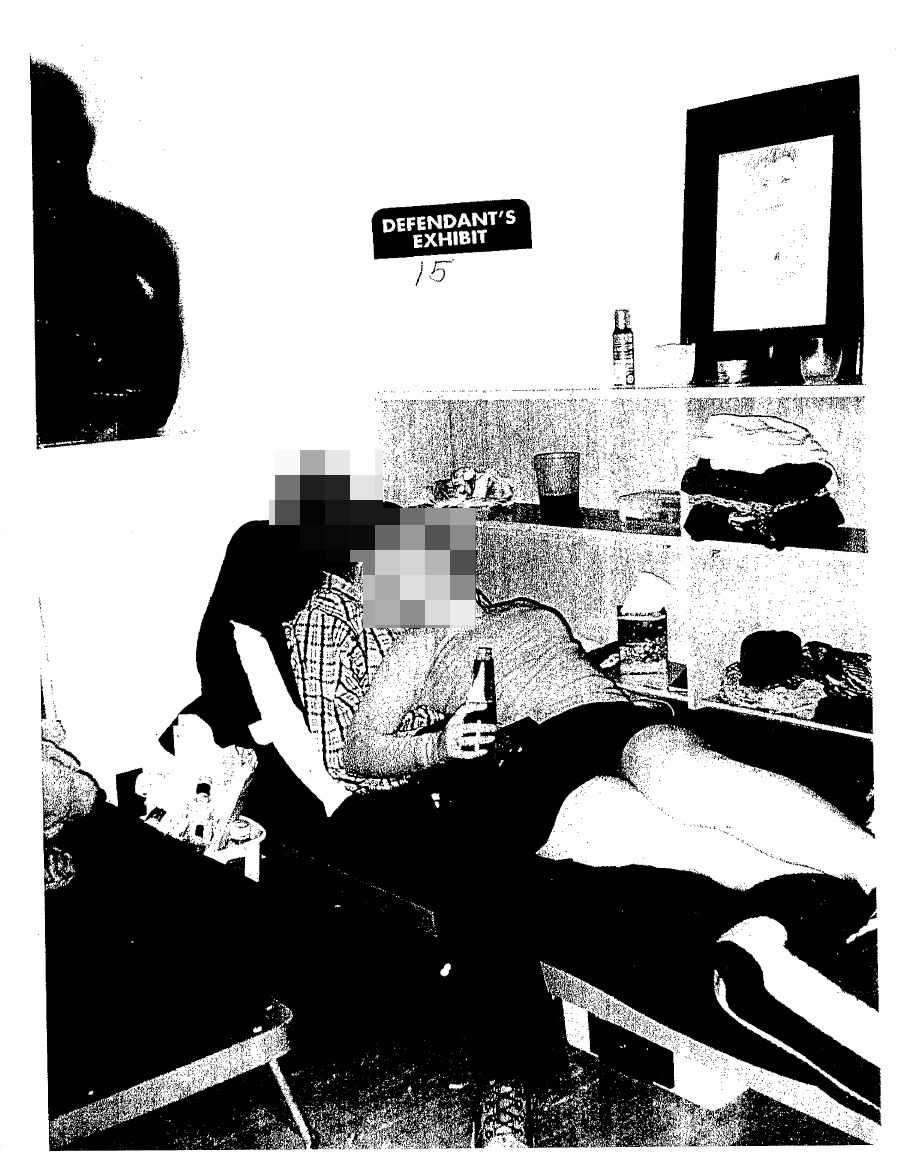

The defense submitted just one photograph of the woman into evidence. Taken in her dorm room at Penn State University, the 8.5-by-12 picture showed her and a friend sitting on a bed. She reclined back — blonde head resting on the man’s chest, body settled between his legs. Facing the camera, the woman grinned, but only slightly.

The image appealed to the defense for three reasons: the empty booze bottles in a trash can beside the bed, the wine cooler in the woman’s hand, and the young black man holding her. (One attorney also mentioned the “shortness of [her] dress.”) The defense’s point: This woman liked to party, and she liked black men — just like Nate Parker and Jean Celestin, the two college wrestlers on trial for allegedly raping her while she was drunk.

Despite the case’s sensational themes — campus rape, underage drinking, racial tension — the 2001 trial didn’t get much attention outside State College, Pennsylvania. Parker was acquitted, while Celestin was found guilty of sexual assault but had his conviction overturned in 2005. The woman filed a civil suit a year later, accusing Penn State of failing to respond to harassment she endured after reporting the assault. This suit, too, went widely unnoticed.

But today, Parker is a rising Hollywood star with a critically acclaimed film — The Birth of a Nation, which Celestin helped conceive. Their collegiate scandal has resurfaced in a different time; the world is more concerned now with campus sexual assault and with holding famous men accountable for past misconduct. Since his first innocence-maintaining interviews about the case, Parker and the film’s distributor, Fox Searchlight, have been dogged by questions about it. This weekend, Parker will give his first press conference since the case’s re-emergence at the Toronto International Film Festival, where the controversy threatens to grab more headlines than the movie — particularly after Gabrielle Union, an actress in the film, expressed her own conflicted feelings about it.

There’s just one thing missing from the story: the woman’s voice. In 2012, at age 30, she killed herself at a rehab facility, her brother revealed last month.

She’s never had more support, even inspiring some to boycott Parker’s film. She’s just not around to experience any of it.

Her absence has been striking — we’re now accustomed to hearing victims in high-profile cases speak for themselves — and confounding for her family and others who knew her. How do you speak on behalf of a woman who spent her final years in “absolute psychosis,” as her sister said, “detached from the reality,” as her brother described her? How do you respect her privacy and requests for anonymity when keeping quiet allows her now-famous alleged attacker to own the narrative?

Amid escalating media coverage, Parker has centered the story on his experience— first on being “cleared of everything” during the “painful” trial, then on his “profound sorrow” after learning of the woman’s death, and finally on his speedy realization that he was “addicted to male privilege and all of the benefits that comes from it.”

Meanwhile, the woman’s life has been eclipsed by the tragic circumstances of her death. We have a clear mental image of her body beside two empty bottles of over-the-counter sleeping pills. What’s lost are the other lives she led: the foster kid who skipped a grade and started her freshman year early at Penn State; the social butterfly who frequented the local all-ages Latin night; and later, the reluctant dropout who felt she couldn’t leave her home, fearing harassment from Parker, Celestin, and their supporters.

Then there’s her life today, as the symbol of a silenced victim. She’s a survivor, joining the growing ranks of women who stand up to powerful men. She’s never had more support, even inspiring some to boycott Parker’s film. She’s just not around to experience any of it.

The woman was the second youngest of four siblings. Her father left when she was 11. At trial, a prosecutor described him and her mother as “bad parents.”

“My mom, she was incapable of taking care of us, and three out of the four children ended up splitting and going into foster homes,” the woman testified. She was 15 when she entered foster care. By 16, she was taking Prozac for chronic depression. Still, she said, she did well in school, skipping the 11th grade. She was an “outgoing, popular girl who loved animals and school,” the woman’s brother told Variety.

She was admitted to Penn State through a program called the Comprehensive Studies Program. “It’s for students that didn’t come from the best homes or wealthy homes, and they provide scholarships enough for you to get into school,” she explained from the witness stand.

She enrolled at Penn State in the summer session before fall 1999. Her major was special education. She earned a 4.0 GPA that summer, she said. She made new friends. One of them — the guy in the picture the defense submitted as evidence — testified that she would come over to his house three or four times a week with friends. She’d bring drinks for the group: wine coolers, Zima, vodka. She was just “doing her thing, going to school, partying, you know, just being a regular college student,” he said.

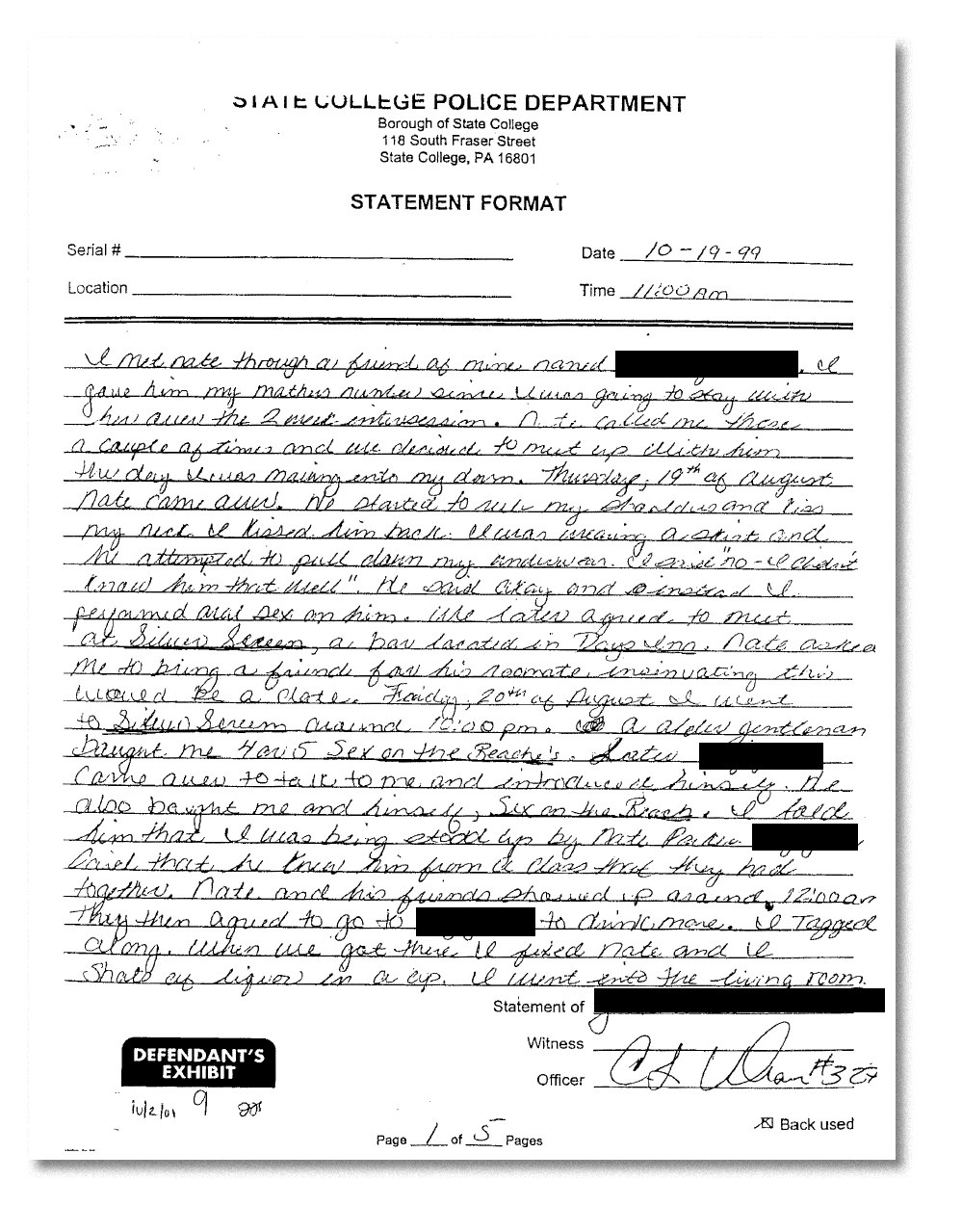

The woman met Nate Parker through a mutual friend just before the summer session ended. She was attracted to Parker and gave him the number for her biological mother’s house, where she was staying until fall classes started, helping to watch over her younger brother, she said. Being at her mom’s didn’t seem to be easy for her. She later told police she returned to campus that August as early as possible “so I could get out” of the house.

Q&A with former Sooner wrestler Nate Parker, the voice of this year's OU Football Intro Video. http://t.co/YmAoMkwPas

She and Parker made plans to meet when she was back at Penn State. The night she moved into her dorm, she hooked up with Parker, giving him oral sex. “I didn’t want to have sex, but I didn’t want to leave it at nothing,” she later said. “I can’t really explain it. I’m not proud of it, but I saw it as being safer and not as big an issue.”

But the next night — Aug. 20, 1999 — she said she was raped by Parker and Celestin, his roommate, while she slipped in and out of consciousness after a night of drinking. The woman said she had been drunk before, but never like that. The next morning, she said she woke to find Parker having sex with her again. He gave her $10 for a cab, and she went home, changed, and showed up to her campus tour guide job. She felt “groggy,” “scared,” “confused,” and “frustrated.” But none of that compared to the pain in her body. "I felt like my whole vagina was torn into pieces,” she said. She made it through a quarter of a tour before needing to go home.

“I didn’t want to lose my college career, you know ... I didn’t know what happened.”

Two weeks later, the woman’s academic adviser urged her to go to the school’s health center, and she agreed when she learned that Penn State would cover medical costs following a sexual assault. She was “tearful” throughout the exam, the doctor who saw her recalled at trial. She was prescribed antibiotics for a potential infection.

She was still reluctant to go to police, afraid they couldn’t do anything for her if she couldn’t even name one of her attackers. But the woman’s roommate, a double major in psychology and African-American studies who was involved with black groups on campus, including Celestin’s fraternity, persuaded her to take action.

“She made the comment about [how] she is proud of every woman that goes and tells the police, and here I am feeling like crap because I didn’t say anything because I was too selfish. I didn’t want to lose my college career, you know,” the woman recalled. At the time, she was taking 13 credits and working two jobs. “And I’m just thinking, you know, I’m such a — I just can’t do this. I didn’t have confidence in the police. I just didn’t want to go, and I didn’t know who, I didn’t know what happened.”

Throughout this period, there was a series of emotional phone calls between the woman and Parker, according to court records. He wouldn’t tell her who joined him that night, denying at times there even was a second guy. But the woman was determined to find out what had happened. On Oct. 13, the woman and her roommate taped one of those phone conversations with Parker, in which she tried to get him to reveal who was in the room that night by faking a pregnancy scare.

She gave the recording to the police and later made an official statement. With police cooperation, she recorded another call, in which Parker admitted that Celestin was the other man in the room. The latter phone call — part of which was published by Deadline alongside an early interview Parker granted about the case — is fairly calm, with Parker standing by his innocence but showing sympathy for the woman. But the first phone call has an entirely different tone. It’s frantic, angry, and expletive-laden, with Parker livid at the woman for making her claims and she livid at him for dismissing them. BuzzFeed News has published it here, for the first time, in full.

The alleged harassment began with a private investigator, the woman said. She was supposed to be anonymous throughout her legal proceedings, but an investigator hired by Parker and Celestin allegedly showed her photo and revealed her identity to people on campus.

The woman began to receive unsolicited harassing phone calls, and Parker, Celestin and their friends yelled “sexual epithets” at her, she said. They followed her around campus, with Parker on one occasion allegedly “stationed” outside her dorm, according to her later lawsuit against Penn State. It became impossible for the woman “to eat or socialize in public areas.”

She filed a harassment report on Oct. 28 to campus police, then wrote to Penn State officials on Nov. 8, asking for help “to ensure her safety,” the lawsuit said. Nine days later, she tried to kill herself “because of the desperate situation she had been placed in as a result of harassment.” She said she’d fallen into severe depression, sleeplessness, and anxiety.

The woman attempted suicide again on Nov. 23. She wrote to the university again on Nov. 25. Penn State had relocated her and her roommate from a dorm to an on-campus apartment, but she said the move didn’t help. She was “tormented,” said S. Daniel Carter, a victim advocate working with the woman through a nonprofit then called Security On Campus, Inc. “It was terrifying, just how out of hand things had gotten in that community."

In December, the woman’s roommate moved out of their apartment. “I was stressed,” the roommate testified at trial. “It affected my everyday life, my grades and everything else … I also lost a lot of friends from standing by her side through everything.” (Her roommate did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.)

The woman formally withdrew from Penn State in January 2000, temporarily relocating to Connecticut. When she returned in March, the phone calls resumed. Her apartment was allegedly broken into that May, “with only her files regarding the attack disturbed.” She moved away again in October — the same month Celestin and Parker returned to the wrestling team — and didn’t come back until June 2001.

By the time the rape trial began that fall, the woman still hadn’t re-enrolled in Penn State. It was too much to juggle school, the case, and her job at the perfume counter at the Bon-Ton department store in the mall, a prosecutor said in his opening statements at the trial.

For three days in a stuffy central Pennsylvania courtroom, attorneys scrutinized the woman’s drinking habits, clothing, mental health, and sexual activity. After Parker was acquitted and Celestin found guilty of sexual assault, the latter was sentenced to six months to a year in jail, to begin after his planned December graduation. Freed on bail, he remained at Penn State while awaiting a judicial affairs hearing on whether he could actually graduate.

At the time, the woman told the Philadelphia Inquirer she didn’t think the situation was “appropriate or fair.”

“I’m really fuming," she said. "I was going on the assumption that someone convicted of a serious felony would be kicked off campus, no matter what."

“She’ll never know what type of person she could have become if she graduated college.”

Still, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that she wouldn’t attend the university’s hearing on Celestin’s fate. “I can’t physically, emotionally do it,” she told the paper. “I’m on the verge of a nervous breakdown.”

“At that hearing, Jean Celestin … the person who assaulted me … would be allowed to question me,” the woman said. “I’ve never spoken to him in my life. I will not do it.”

Celestin was ultimately expelled from Penn State for two years, delaying his degree, despite an attempted student government resolution to let him graduate. Meanwhile the district attorney appealed what he called Celestin’s “lenient sentence” — sexual assault typically carries three to six years in Pennsylvania — and in 2004 Celestin was re-sentenced to two to four years. At that hearing, Assistant District Attorney Lance Marshall said of the woman, “She’ll never know what type of person she could have become if she graduated college.”

In 2005, Celestin’s conviction was overturned and he was granted a new trial. The woman made no public statement, but Marshall told the Penn State Daily Collegian that “she was upset. She doesn’t want to have to do this again.” She didn’t end up needing to; the new trial never happened.

The woman died in April 2012 at a drug rehab facility in Quakertown, Pennsylvania. Speaking to The Daily Beast, the woman’s sister said that before ending back up in Pennsylvania, the woman moved around from Maryland to Florida to Georgia, where she’d picked up a K2 — or synthetic marijuana — habit. Her son, who was born in 2002, was being raised by a friend.

The woman reportedly developed severe psychosis, believing she and “other people were Christ and Satan” and eventually leaving “religious rants” behind on her laptop, her sister said. The family came to fear the woman, and she reportedly spent time in a mental institution.

Over the years her case was active, the woman seemed to struggle with her anonymity; her desire to tell her story was hindered by her fear of retaliation. Her outing by a private investigator on campus in 1999 contributed to her dropping out, she said, and she chose to remain a Jane Doe when she filed (and then settled) her lawsuit against Penn State. Yet the woman “eagerly sought out opportunities to explain her side of the story,” Carter told BuzzFeed News. “She needed to speak out to keep this from happening to someone else.”

In 2002, she gave an on-camera interview for the first and only known time to a local news station, effectively outing herself. This August, the footage was quietly aired by CBS This Morning and Inside Edition. Both outlets referred to the woman by her full name — also a first.

“I won’t go on campus,” the woman said in the clip, wearing a green ribbed sweater, her wavy, shoulder-length hair parted down the center. “I won’t go to Walmart or the grocery store by myself. I won’t even go shopping alone… I’m in my hometown and I can’t even feel safe. I’m in my hometown and I can’t even go anywhere without being fearful.”

Watching the clip, it’s easy to imagine she might have come forward again if she were alive today. Like many sexual assault survivors — including, recently, the girl who was sexually assaulted at St. Paul’s School — the woman might worry about her privacy but ultimately feel more compelled to expose the men and speak up for other women. But the woman didn’t have what many survivors have today; there were no local groups surrounding her with support, publicly rallying to her side. Her nearest supporters were 200 miles away in Philadelphia, Carter said.

“I’m in my hometown and I can’t even feel safe. I’m in my hometown and I can’t even go anywhere without being fearful.”

Today, the decision to come forward is no longer hers. It’s been transferred to her relatives and former representatives — the ones left to speak for her. And they don’t seem to agree on the best way to do that.

A statement issued by the woman’s family to the New York Times expressed appreciation that “these men are being held accountable for their actions” but said they were “dubious of the underlying motivations that bring this to present light after 17 years, and we will not take part in stoking its coals.”

“While we cannot protect the victim from this media storm, we can do our best to protect her son. For that reason, we ask for privacy for our family and do not wish to comment further.”

It was clear not everyone was on board with the statement. The woman’s sister — the same who offered deeply personal details of the woman’s troubled final years to The Daily Beast — told the Times the statement didn’t represent some family members or, more notably, the woman’s wishes.

“I know what she would’ve said … ‘I fought long and hard, it overcame me,’” the sister told the Times. “These guys sucked the soul and life out of her.” The woman always believed “there were other victims,” her sister said.

But Carter said at the height of working with the woman on her case, he’d speak with her daily, and he had no reason to believe her family was even involved in her life at the time.

“If they were, I had no knowledge of it or contact with them,” he said. “It was very apparent she did not have the support of even a conventional family structure to fall back on.” (Members of the woman’s family did not respond to BuzzFeed News' requests for comment.)

Carter declined to speak with any more specificity about the woman, citing her anonymity and client confidentiality, but pointed out that she was a kind of pioneer. Lawsuits like the one she filed against Penn State are fairly common today, but back then, Carter said, they were just starting to emerge. The Women’s Law Project, which represented her in the 2002 suit and reportedly placed her in the rehab home where she died, has declined comment, also citing her anonymity, yet it recently issued a lengthy statement about the case, centered on the need for updated sex crime laws.

Parker’s supporters too seem to be wrestling with how to speak on his behalf — namely how to defend him while the woman is unable to defend herself. In what Slate called a “glaring affront,” four Penn State alumni recently wrote an open letter about the case’s re-emergence, in which they rejected the suggestion by the woman’s brother that the “one moment … she changed as a person” was the trial.

“Misinformation suggests that a spiral into depression was triggered by the alleged incident in 1999,” wrote the alums, including two who testified on Parker’s behalf at the trial, one of whom later co-founded the Nate Parker Foundation. “However, court records and testimony by medical professionals revealed a history of chronic depression that dated back to childhood and the use of antidepressant medication that preceded this event.”

The supporters’ statement is true — her depression was pre-existing. But the woman’s brother also had a point — trial lawyers questioned the woman’s mental state extensively, but there were no signs, no testimony given, and no notes in police or medical records to indicate the woman suffered mental illness beyond chronic depression. All accounts point to the woman developing what her death certificate described as “psychotic features, PTSD,” and “polysubstance abuse” in later years, complicating the questions of when, how, and why the woman lost control of her life.

With the woman unable to speak for herself, it’s impossible to answer and irresponsible to guess at these questions. But as her story reaches further than she could have anticipated, more people are trying to do just that — and questioning whether they’ll support Parker when The Birth of a Nation hits theaters in October.

When Parker first addressed the re-emerged scandal, he cast himself as a victim. When confronted with backlash to that approach, he explained his behavior in a way that placed blame not on himself but on social justice concepts: “hyper-male culture” and “toxic masculinity.” Back in 1999, he told the woman he had “too much to lose” and “too much riding on myself” to “take advantage of a girl.” This is a man who’s always been looking out for his future.

The woman didn’t have one. ●