Dead people continued to be charged fees for years by the Commonwealth Bank (CBA) for financial services they didn't receive because ... well ... they were dead.

This is just one of several bombshell revelations to come out of the ongoing royal commission into the financial services sector.

During the Commonwealth Bank's appearance before the royal commission on Thursday, commissioner Kenneth Hayne heard that in a 2015 compliance and risk report prepared by the bank, and provided to the commission, the bank reported that one of its advisers continued to provide services to a client eight years after the client died.

"Ongoing services have not been provided to clients," the bank document stated. "One file client dies in 2007. Contact made with deceased wife in 2013, but no action taken."

The report recommended the adviser receive a formal warning.

In another incident regarding services provided from 2003, an adviser was aware the client died in early 2004, but continued to collect fees for more than 10 years after the client's death.

"When asked, [the adviser] said he didn’t know what to do and he had tried to contact The Public Trustee and had not heard back," the document stated.

CBA is in the process of repaying $100 million in fees to customers for services they never received. The five largest banks are paying a total of nearly $200 million back to hundreds of thousands of customers for services they didn't receive.

Earlier this week, AMP was under fire after it was revealed during the royal commission it had charged customers financial planning fees for 90 days, when those customers were not receiving financial planning advice.

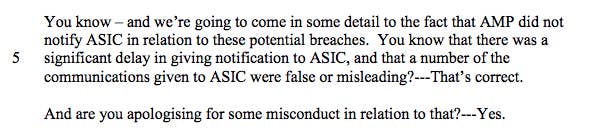

In submissions to the commission, AMP apologised for the breaches. When AMP executive Anthony Regan was asked why AMP was apologising, he said it was for the breaches, and for misleading the corporate regulator, ASIC, about the breaches.

"Well, for example, we know that we have 45 committed breaches in relation to retaining fees on client accounts where fees have been charged where they shouldn’t, and we know that that is a breach," he said. "So that is a breach of our licence condition, and that’s what I’m apologising for."

He then acknowledged not informing ASIC at the time.

The reaction to Regan's testimony has resulted in the first scalp for the royal commission, with AMP CEO Craig Meller resigning on Friday.

In a press release on Friday, AMP said it "apologised unreservedly for the misconduct and failures" and Meller would resign immediately as a result.

Earlier hearings also revealed that staff at NAB were allegedly paid cash bribes for dodgy loans given to customers.

All this evidence is super awkward for the Turnbull government. Labor and the Greens had been calling for a royal commission into the banks for years, and the government only gave in when it looked like it was going to lose a vote on it in the House of Reps.

Treasurer Scott Morrison at one point said the calls for a royal commission were a "populist whinge". In a press conference on Friday Morrison said he wouldn't engage in political point scoring on the issue.

Morrison and financial services minister Kelly O'Dwyer announced on Friday an increase in penalties for people who breach the Corporations Act (such as misleading ASIC). Criminal penalties will be up to 10 years in jail for individuals, or $9.45 million in penalties for corporations (or 10% of turnover, if turnover is larger).

Civil penalties will be increased to a maximum of $1.05 million for individuals, and 10% of turnover for corporations.

ASIC will also be given the power to ban people from working for financial services companies, as well as extra investigatory muscle, including the power to access intercepted communications.

In the last financial year ASIC only managed to achieve 10 criminal prosecutions, and of those, six people were given custodial sentences, including those who had suspended sentences (meaning no jail time).

O'Dwyer said the increase in penalties will help the courts to consider the scale of the misconduct and the appropriate punishment.

"If you push the boundaries out, you make sure that those people who are committing serious misconduct or even just misconduct will be dealt with far more severely," she said.