The law offices of Jay Leiderman occupy the third floor of a beige building in an unlovely office park across a busy road from a strip mall that features a martial arts studio, a discount tool mart, and a vape shop called “Vapes!” Here in Ventura, California — known variously as “Ventucky,” “Bakersfield by the sea,” and, per one Urban Dictionary entry, “the armpit between Santa Barbara and Malibu” — the locals tend to get charged with crimes like driving under the influence, simple assault, and possession of methamphetamine. It is not exactly a hotbed of hacking, making it a bit of a strange location for an attorney who may be the best-known defender of people accused of computer crimes in the United States.

And yet here comes Jay Leiderman, pulling into a pine-shaded parking lot in a milk-white Maserati Ghibli. Over the past five years, Leiderman has turned himself into one of the central figures in the small world of lawyers who regularly defend hackers. If the Justice Department indicted you tomorrow for doing something on a computer that you shouldn’t have been doing, it’s almost certain that within a few short hours you would hear Leiderman’s name. That might be because he’s already written about your case to his thousands of followers online. It might be because your lawyers need advice themselves. Or it might be because Leiderman is already your lawyer.

The thing is, the Justice Department doesn’t prosecute many people under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the federal statute that governs computer crimes involving “unauthorized access.” The people it does come after are usually young and unable to afford high-quality representation. Consequently, even America’s most prominent defenders of computer criminals don’t defend them all the time, or even most of the time. And when they do, they often work for free, or close. That means, in 2016, it isn’t possible to have a solvent criminal law business solely devoted to defending hackers. And so the vast majority of people who trickle into Leiderman’s practice have nothing to do with the CFAA. Most of them probably have no idea what the CFAA is, or that their criminal defense attorney has an international reputation defending people accused of violating it. Neither, for that matter, do many of Leiderman’s local colleagues. No, one of computer law's loudest voices — the attorney who has represented some of the country’s most famous hackers and who keeps an encrypted chat app open at all times so he can dispense ad hoc pro bono legal advice to members of Anonymous — spends much of his time defending the kinds of clients Matlock might turn down on a good day and keeping Ventura’s marijuana professionals out of trouble. Most days, he can’t even have an IRL conversation about his biggest cases. Which is a shame, because Jay Leiderman really loves to talk.

“Most people coming in here are having the worst day of their life. They don’t need some stuffy asshole who is dead inside.”

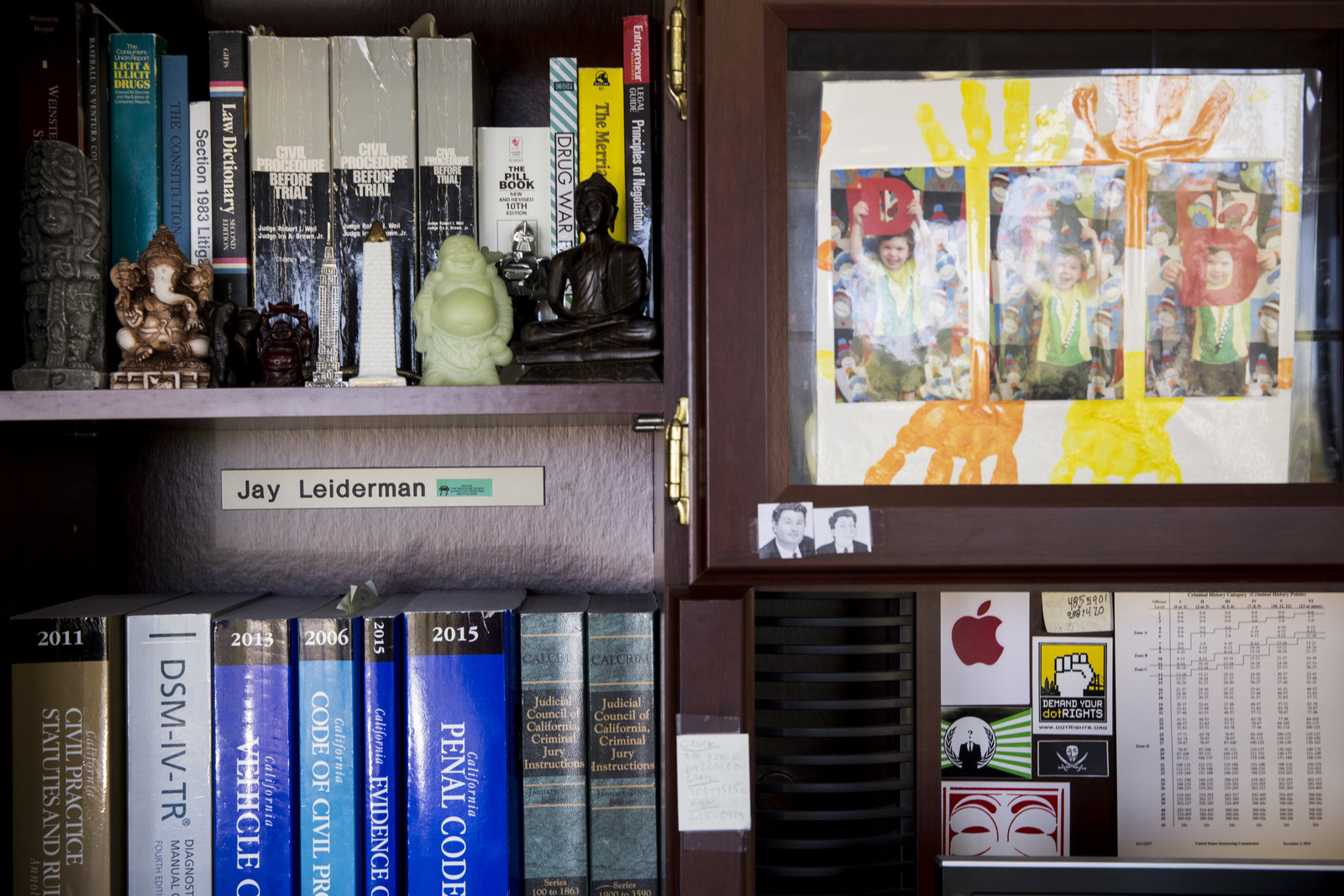

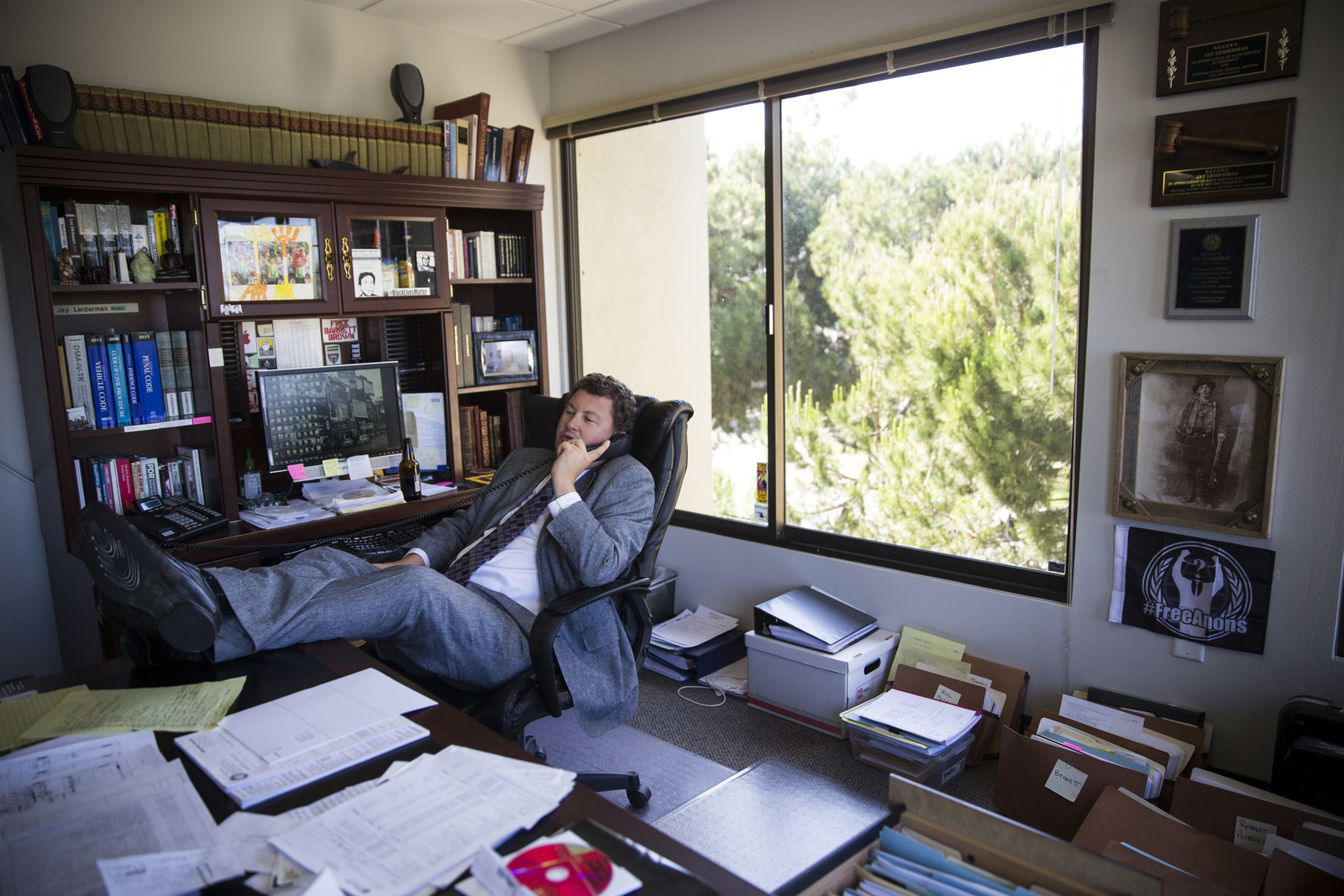

One such local client: Michael Bogdan, who arrived at the office unannounced on a recent Monday morning. He walked through reception — past a legal assistant, past twin charcoal portraits of the imprisoned hacker Jeremy Hammond and journalist Barrett Brown, past a framed copy of a Ventura County Star feature identifying Leiderman as “one of the top attorneys in the country for people accused of violating the federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Act,” past several framed pieces of Grateful Dead album art — and into the corner office. Leiderman, having paused a bootleg 1978 live performance of the Rolling Stones’ “Some Girls,” spun in his chair to face his client, a shambolic-looking white man with a dead tooth.

“You’re here?” Leiderman said. “You’re here!”

Bogdan had been calling all morning about a hearing in his case, which was typical of Leiderman’s often bizarre workload. The 39-year-old movie memorabilia dealer had slowly been going blind since 2004 and had recently started paying porn stars for sex, or, as Leiderman put it, “enjoying his sight while he’s still got it.” Last year, after a relationship with one such escort soured — she claims he was harassing her on social media, while he claims to have become enraged after she asked him to pay her to exchange text messages — she took out a restraining order against him that included his writing online. Bogdan hired Leiderman to get that part of the order lifted as a prior restraint on speech. Now Leiderman was trying to work out a deal with her lawyer that would keep them away from each other while still letting Bogdan write about their relationship on his own website, The Porn Star and The Blind Man.

“It’s always something!” Leiderman said,

laughing as he located, with clairvoyant speed, a piece of paper buried on his

anarchic desk.

Bogdan’s was just one of 26 open cases for Leiderman as of early April; other clients included a man accused of drunkenly stealing a dirt bike from the pit of a motocross rally, a teenager who shot up his own house with his father’s gun to distract his parents from the fact that he had missed his curfew, a Hell’s Angel with a gun charge, a man accused of molesting a 10-year-old, and assorted drunken misdemeanors. Also among them were a handful of court appearances he was making on behalf of a friend and former officemate who had not totally unexpectedly killed himself the week before.

And then there was the case of Matthew Keys, the former Reuters social media editor who had been convicted the previous October of conspiring to hack the website of the Los Angeles Times and who faced up to 87 months in prison. His sentencing hearing loomed in two weeks in federal court in Sacramento.

If Leiderman, who is 45, was exhausted or grieving, he didn’t show it. For one thing, such was the slew of tasks at hand that he had taken up coffee just that week, and he was on his second cup of the day. (“I don’t drink coffee!” he said, over a steaming mug, as if he had surprised himself.) For another, his two most salient features, extremely blue eyes and extremely shrewd eyebrows, in combination with his cherubic face, gave Leiderman the aspect of a man perpetually on the verge of a wonderful prank. Also, this was a non-court day, so he dressed all the way down: a black T-shirt screen-printed with the image of a roaring tiger, stonewashed jeans with torn-up knees, and Adidas Sambas. “Most people coming in here are having the worst day of their life,” Leiderman said. “They don’t need some stuffy asshole with gray hair who is dead inside.”

Whatever the reason for the getup, it was most definitely a vibe. Here was an utterly local lawyer costumed as a forgotten John Hughes protagonist; driving an expensive Italian sports car; presiding over an exuberantly disordered office; who was possibly repressing some heavy-duty mourning; who, by the way, had some pretty deep connections with Ventura County’s medicinal cannabis community; who lived basically a double life as counsel to the internet’s undesirables; all the while a bitter john with too much time on his hands hovered weirdly over his desk. There was a slight but unmistakably zany whiff of Saul Goodman in the air.

It was more than enough to make one wonder: How had this guy become the face of criminal defense for hackers in America? And, relatedly: How was this guy going to keep Matthew Keys out of prison?

“Every Monday something always fucking happens!” Leiderman exclaimed, in response to something on his phone, though he did not seem to be complaining.

On March 18, 2013, a Monday, Jay Leiderman went on HuffPost Live to discuss his newest client, Matthew Keys. Keys had been indicted the previous Thursday by the U.S. government, which alleged that he had passed login credentials to members of Anonymous in an internet chat and encouraged members of the hacking collective to deface websites owned by the Tribune Company, his former employer, against which he had a grudge. According to the indictment, an Anonymous member named “Sharpie” had used that information, at Keys’ bidding, to change the headline of a Los Angeles Times article to “Pressure builds in House to elect CHIPPY 1337,” a reference to a hacking group. The defacement was live for about 40 minutes.

In the dazed hours after the indictment, Keys received an email from Tor Ekeland, probably America’s other best-known CFAA defense attorney, whose client, the hacker Andrew “weev” Auernheimer, told him to take the case. But Ekeland wasn’t licensed in California, so he had to find someone to take the case with him, pro bono. His first thought was Jay Leiderman, whom he knew by reputation. (It helps when you are only one of a few lawyers who does what you do.) In Leiderman, Ekeland found a “street-smart trial lawyer” who was “extraordinarily quick on his feet.”

On HuffPost Live, Leiderman had a lot to say about Matthew Keys. If his client had wanted to get back at his former employer, he would be facing less jail time if he had “beat him with a baseball bat” and “spray-painted all the computers and walls of the Los Angeles Times,” and so didn’t you have to ask yourself, “Is our government incentivizing physical violence?” Also, if his client had even been in that internet chat, he had been there as “sort of an undercover-type, investigative-journalism thing.” Also, come on, what his client had been accused of doing was totally not that big of a deal.

“No one was hurt, there were no lasting injuries, no one's identity was stolen, lives weren't ruined,” Leiderman had told the Associated Press. “It was a joke, and I guess a joke will get you 25 years in prison.”

Leiderman was far from alone in making this argument. The CFAA, introduced in 1984 and expanded in 1986, is widely loathed among internet activists, security researchers, and many lawyers in the field, who see the law as an “egregiously overbroad” relic that has led to a chilling effect on legitimate work, and that protects the rights of powerful corporations and government agencies while endangering ordinary web users.

In particular, the central phrases in the law, which forbid “unauthorized access” of a “protected computer,” can be interpreted so widely as to include behavior as mundane as password sharing. Worse still, the law carries exorbitant statutory maximum sentences; Keys was looking at a maximum prison term of 25 years. That's partially because the CFAA is subject to the “Economic Offenses” subsection of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, which adds “offense levels” in proportion to the monetary loss incurred by the crime. In a forthcoming paper in the George Washington University Law Review, the computer law scholar Orin Kerr argues that CFAA offenses should be considered crimes of trespass, not fraud, and that loss should be a secondary factor in calculating sentences. The law professor and media scholar Tim Wu has called the CFAA “the worst law in technology.”

“It was a joke, and I guess a joke will get you 25 years in prison.”

The January before Keys was indicted, Aaron Swartz, a 26-year-old programmer and activist, hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment in the face of 35 years in prison. He had been indicted in 2011 under the CFAA after downloading millions of articles from JSTOR, an archive of academic journals. Even before his death, Swartz was an internet folk hero: He co-founded Reddit and co-developed RSS. His alleged crimes were high-minded, or at least principled — he had long been an advocate for democratizing access to information. Swartz’s indictment had given anti-CFAA advocates a powerful symbol of the way the law can crush good people and good work; his suicide robbed them of a plaintiff who could have helped make a profound case against the law in court.

The CFAA-amending Aaron’s Law Act, named for Swartz, has been introduced in Congress twice but has never come up for a vote. Among the reasons why CFAA reform has moved so slowly may be the fact that the mandatory maximums, while alarming, are almost never applied, and that there simply are not very many CFAA prosecutions, full stop. According to Kerr, the federal government brings about 100 CFAA prosecutions a year. That’s because CFAA violations are extraordinarily difficult to find and prove.

Indeed, the government tends to prosecute CFAA cases only when it has a strong chance of securing a conviction, as it did against Keys, who had confessed to the crime in a taped interview with an FBI agent — a confession Keys said he gave while whacked out on prescription pills. This puts attorneys like Leiderman in a strange situation: How can you argue simultaneously that your client is innocent and that taking your client to court for the not-very-harmful thing that your client kind-of-maybe-probably did is wild prosecutorial overreach?

The government offered Keys a plea deal, which, according to Keys, did not rule out the possibility of a short prison sentence. He rejected it. That meant it was up to Leiderman and Ekeland to take apart the government’s case that Keys did it. And failing that, to take apart the law that made what he kind-of-maybe-probably did a crime.

Though everyone in Jay Leiderman’s family told him he should be a lawyer, it took Jerry Garcia to truly convince him.

Born in Queens in 1971 to a toy executive and a sixth-grade teacher, Leiderman grew up in upper-middle-class Rockland County, about an hour's drive north of the city. The highlights of his early childhood revolved around a yearly trip with his father to Toy Fair, the annual industry convention, which he left one year with a box full of Star Wars figurines and another year with a photo beside Lee Majors, the Six Million Dollar Man. (That one sits on a bookshelf in his office.) In high school, he nursed two obsessions, both musical: punk rock and the Grateful Dead. That meant dozens of shows at CBGB in the mid- to late 1980s. It also meant, after the Dead burst through to a new generation of ears on the strength of 1987’s “Touch of Grey,” the beginning of a lifelong fandom.

“I’ve seen them, I would guess, exactly 164 times,” Leiderman said.

The law professor and media scholar Tim Wu has called the CFAA “the worst law in technology.”

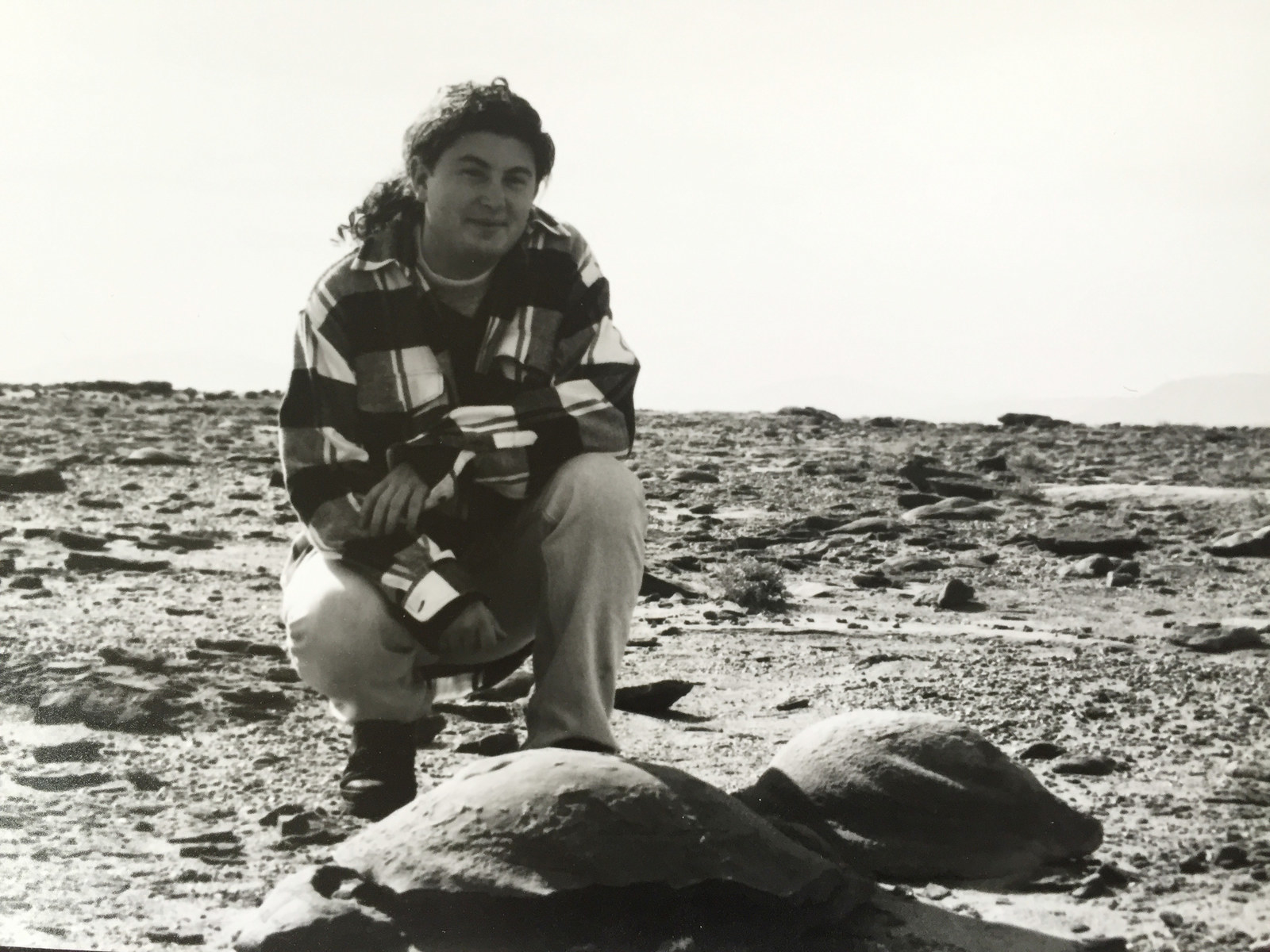

After graduating Michigan in 1993, Leiderman and his friends loaded up a “roadworthy” blue Volvo station wagon with camping equipment and set out to follow the group across the country, full-time. There they joined thousands of other Deadheads hawking everything from burritos and blown glass to nitrous oxide and tie-dye to fund their travel. A friend made frequent trips to Nepal, where he bought and brought back T-shirts that the group flipped for an $8 profit on every shirt. Outside shows, Leiderman would stand on a blue tarp, shirtless, wearing denim cutoffs, a fanny pack, and Birkenstocks, with dozens of the shirts spread out before him. The group made enough money to live and travel, staying 12 people in a hotel room. The ride lasted for two blissful years. Along the way, Leiderman soaked up the group’s post-’60s ethos of personal and political freedom.

“We were so on our own. We weren’t bound by any conventional rules. We felt that we were America’s last tribe,” he said.

Then, on August 9, 1995, Jerry Garcia died of a heart attack in his room at the Serenity Knolls treatment center. The Dead disbanded. The organizing force of Leiderman’s life was suddenly gone.

“My whole life changed,” Leiderman said. “Everyone I knew, all my friends, were all in flux. Were we going to scatter to the four winds? Ultimately, people did.”

But Leiderman remembered something his grandfather had told him: If he wanted to turn his idealistic streak into social change, he had to work from inside the system. Plus, his parents had always told him that he would make a good lawyer. Plus, “I didn’t know what the hell I was doing,” Leiderman said. So, the weekend after Garcia died, Leiderman began his law school applications. He showed up for classes at the University of San Francisco Law School the following summer with hair halfway down his back, and left in 1999 as the class president. He applied to public defender jobs around the country, and picked Ventura because of the weather. He thought he’d stay 10 months.

Every day after court closes, many of the men and women who make their living in the Ventura County Hall of Justice proceed to the Victoria Pub and Grill, where they gossip, laugh, bitch, play darts, and drink. Victoria’s is dark, big, and cheap: a good bar. It is also stumbling distance from Leiderman’s office. He has been coming here for 16 years, ever since he started working as a lawyer.

On that recent Monday, now in the mid-afternoon, Leiderman was joined at Victoria’s by a group of his friends, all of whom had worked together as young lawyers at the Ventura County Public Defender’s Office. They had a table that was “their table.” They had drinks that were “the usual.” The mood at the bar was initially somber; nearly everyone there had been at the funeral of Leiderman’s friend the day before. Eventually, after a round, the talk turned to the group’s early days as lawyers.

In his first week on the job, Leiderman was assigned the case of a homeless man who had been charged with stealing a shopping cart. When he reviewed the facts, he discovered that the shopping cart came from a store that had been closed for 30 years. Leiderman filed a barrage of pretrial motions, and the judge threw the case out.

“On to bigger and better things,” Leiderman told his boss, the chief deputy public defender, afterward.

“Wait a minute,” his boss had responded. “You will go on to bigger things, but you may never do a better one.”

The case left an impression on Leiderman. He saw just how disproportionately and arbitrarily governments could prosecute their weakest subjects. He also saw that thorough, competent lawyering could make a life-altering difference to powerless people accused of crimes.

“We weren’t bound by any conventional rules. We felt that we were America’s last tribe."

Within a year at the VCPDO, Leiderman had graduated from misdemeanors to murders and three-strike cases. He sought out a series of cases defending the homeless, successfully challenging an open-container law that was frequently used to round up Ventura’s large indigent population and getting a raft of misdemeanor illegal camping charges — also used as a weapon against the homeless — thrown out so decisively it led to an internal city review.

“It pissed me off, it was a horrific injustice, and it was the right thing to do,” Leiderman said.

Leiderman’s years at the VCPDO coincided with the passage of California’s medical marijuana statute, and the young lawyer started taking possession for sales and illegal cultivation cases. By the time he opened a private practice, in 2007, Leiderman had become something of an expert in state and county compliance laws. In addition to defending clients from marijuana-related criminal charges, Leiderman also advises medical marijuana collectives, teaching them the law, writing up their contracts and articles of association, and waiting on retainer for run-ins with the police. It’s a major chunk of his business. Though Leiderman no longer tokes — it makes him too paranoid — he sees this work as directly related to his CFAA practice.

“It’s another way the government is invading our life unnecessarily,” he said. “This is a plant that has been used medicinally for 5,000 years. That we know of.”

In 2008, Leiderman started dating Justine Avtjoglou, also a public defender. (“Aside from my wife, I am the best lawyer in my house,” reads Leiderman’s Facebook biography, in part.) On President’s Day in 2011, they discovered that Avtjoglou was pregnant. They married that Friday, on the upper level of Victoria’s.

Now the Leidermans live in a large stucco house in the Ventura Hills with their son Lydon, named for Johnny Rotten. In the garage next to his Maserati — leased, according to Leiderman, with some of his fee for securing a reduced sentence for Andrew Luster, heir to the Max Factor cosmetics fortune, who had been serving 124 years for drugging and raping three women — sat racks and racks of bootleg live rock and reggae CDs. A huge green Anonymous flag hung over the car.

If he has any qualms about making Maserati money off of representing a convicted rapist, Leiderman doesn’t show it. When it comes to taking what he calls “the ugly cases” — the Andrew Lusters, the child molesters, the gun-toting, curfew-dodging teenagers — Leiderman is very much a defense attorney’s defense attorney. “It is my duty under the constitution to represent these clients,” he wrote in an email. He has even, with some acrobatics, figured out a way to fold these cases into his civil libertarian worldview. “I am what stands between the police state and the tyranny of ever encroaching government. If we abandon the ugliest of the cases, before we know it we're back to sending people to prison for a joint.”

In the fall of 2010, Leiderman, like many Americans, started reading about Anonymous, the hacktivist collective that brought down the websites of PayPal, MasterCard, and Visa in retaliation for cutting off service to WikiLeaks. It was a heady time for the organization, which experienced a run of successes between the PayPal hack, the hack of the security tech firm HBGary, a distributed denial of service, or DDoS, of the Westboro Baptist Church, and activity in support of the Arab Spring. “There was invincibility in the air,” Leiderman said. “They were so far ahead of the FBI. Back then they didn’t have allies — they had fans.”

Fascinated by the group, and buoyed by his success with medical marijuana, Leiderman realized that there would be litigation against its members. In the spring of 2011, while Avtjoglou was pregnant with Lydon, Leiderman tweeted that he would represent “righteous hacktivists” pro bono.

One of the responses came from Christopher Doyon, also known as Commander X, or the “Homeless Hacker.” A member of Anonymous, Doyon in 2010 allegedly launched a DDoS attack against the Santa Cruz County website as retaliation for the breakup of a protest against a law forbidding overnight camping. The law was widely seen as a measure of controlling the homeless population. Doyon, who feared arrest, started meeting Leiderman in secret. Leiderman did his part, instructing his office to refer to Doyon only as “Thomas Paine” over the phone.

In Doyon, Leiderman had found a client who shared his love of the Grateful Dead. But more than that, he had found a client who wasn’t just a hacker but also a liberal activist, someone sticking up for a free tribe, someone who helped him continue to draw the connection between the ideals of his counterculture past and legal present. Today Leiderman sees hackers as part of a grand narrative of American counterculture — at least the parts of it with good music.

Leiderman sees hackers as part of a grand narrative of American counterculture — at least the parts of it with good music.

“The Grateful Dead is counterculture based on the idea of changing the world through conversation and education,” he said. “Punk is like, you know, fuck you, we’re going to change the world through being loud and in your face and forcing you to see the ugly. Hackers are like, fuck you, man, we can change the world because we can beat you at your own game.”

His experiences with Doyon familiarized Leiderman not just with the basics of the CFAA but also with that time-honored side effect of participation in the activist counterculture: a healthy sense of paranoia. In September 2011, Leiderman and Doyon exchanged emails about a forthcoming meeting at a Mountain View coffee shop. As he drove there, Leiderman got a phone call from his office: His client had been arrested.

“I can’t prove anything, but you know,” he said, “I’m sure the FBI are in my computer somewhere.”

After Doyon’s bail and subsequent flight to Canada, Leiderman, never a technophile, got serious about security. Anons showed him how to set up encrypted chat and email. And he began to keep up a constant conversation, via Wickr, with members of the group, which continues to this day.

He also became involved in a passel of other hacking cases. He consulted on the plea deal for Jeremy Hammond, who hacked the private security firm Stratfor. He helped manage the defense fund for Deric Lostutter (aka KYAnonymous), the hacker who doxxed the high school football players in the 2012 Steubenville, Ohio, rape case. He pleaded the LulzSec hacker Raynaldo “Royal” Rivera down from a maximum of 15 years in prison for hacking Sony to a year and a day. He helped on the defense of one the “Fappening” hackers. And he consulted on dozens of other cases. Along the way, he became an expert, sought out for television hits and newspaper quotes.

“Jay understands the subculture of Anonymous and computer hackers better than any attorney,” Matthew Keys said. “He has an encyclopedic knowledge of this culture. He gets it.”

Leiderman claims not to have any advertising — that universal sign of the sleazy defense attorney — and it’s true that there are no roadside billboards in Southern California bearing his face. But he has figured out a remarkably effective, if time-consuming, way of keeping his name out there: a relentless internet presence. On Twitter, Facebook, and his professional blog, all of which he updates constantly, Leiderman posts news, legal analysis, musings, and the odd meme related to his cases.

Courtesy Jay Leiderman

The relative paucity of CFAA cases enables attorneys who have litigated one or two to market themselves as experts. Five years since he first became involved with the world of hacking, Leiderman has, between trials, settlements, and consultations, worked on about 50. That allows him to claim, if not mastery, ubiquity.

Yet through it all, he’s remained a fixture in Ventura. After a few rounds at Victoria’s, a district attorney with a powerhouse of a mustache sidled up to Leiderman, who was between him and the dart board. They exchanged pleasantries. Leiderman said that life was good, thanks, and that he’d be heading up to Sacramento soon to work on one of those crazy hacking cases he had a practice in.

“Huh,” said the DA. “I had no idea.”

In January 2014, Leiderman and Tor Ekeland filed a motion to suppress Matthew Keys’ taped confession. The attorneys claimed that Keys’ statement was inadmissible because he was disoriented from a combination of sleeping pills and a new antidepressant when he waived his Miranda rights. In May, U.S. District Judge Kimberly Mueller denied the motion.

The inclusion of the confession put the defense at an enormous disadvantage in the trial, which started last September, more than four years after the alleged crimes. In the tape, Keys says, “I did it,” and admits to being AESCracked, the user who chat logs show gave out login credentials with the instruction to “go fuck some shit up.” It’s damning. The confession allowed the government to tell Keys’ story as a “bitter, expensive, exhausting tale of online anonymous revenge against a media organization,” as Assistant U.S. Attorney Paul Hemesath put it in his closing.

The defense attorneys didn’t put on a case. They didn’t call any witnesses. They didn’t try to establish an alibi or a thorough alternative narrative for the crimes. Instead, they tried, at every turn, to slow down and frustrate the government’s introduction of evidence and claims about loss.

“Jay understands the subculture of Anonymous and computer hackers better than any attorney.”

The government called witness after witness from the Tribune Company to recount an elaborate corporate response to the breach. At the end of each witness’s testimony, the prosecution asked them to estimate how many hours they spent working on the hack, information the government then used, based on salary, to calculate loss. Most of the 10 witnesses made more than $100,000 annually.

The defense went to work attacking the loss figures. Leiderman harped on the fact that the prosecution’s witnesses all recorded their time in “very tidy hour, half-hour increments” that were “unreliable … the essence of reasonable doubt.” Leiderman and Ekeland also made repeated reference to an email sent by Keys’ former supervisor to a Tribune attorney reading, “By the way, if you bill $1000 an hour, that would help us get this prosecuted”; it was a reference to the $5,000 figure the government needed to reach to justify bringing a felony charge. The supervisor claimed on the stand that the email was a joke.

If the jury had a hard time deciphering the truth about the loss figures, it also had to contend with the law itself. The CFAA is an extraordinarily complicated and technical statute, and after congratulating the jury for staying awake through the trial, Leiderman spent much of his closing simplifying. He again attacked the government’s loss calculations. And in the face of his client’s confession, Leiderman turned to a big-picture, commonsense argument about the nature of the prosecution itself.

“This is not exactly the most unforgettable act of hacktivism ever there was, but here we're in a federal case,” Leiderman said. “And I don't know if you know the expression ‘Don't make a federal case out of it.’ My grandpa always used to say that to me, and now I say it to you.”

In the end, the government’s evidence was too strong. After a day of deliberations, the jury found Keys guilty of all three counts. If Leiderman was going to keep his client out of jail, he would have to convince the judge.

The April morning of the sentencing hearing was warm and clear. Justice had a good view: From the 14th floor of the federal courthouse that towers opaquely over downtown Sacramento, plate-glass windows look out for miles over the city and the Sacramento River to the west. The members of the prosecution team, led by Matthew Segal, the chief of the Special Prosecutions Unit for the Eastern District of California, had arrived early and were sitting on spectator benches with big white spiral binders balanced on their knees. Minutes before the hearing was set to start, there was no sign of Keys or his lawyers.

“Has anyone seen Jay or Tor?” Segal asked.

Finally, the double doors of the courtroom swung open and Leiderman, Ekeland, and Keys walked through. Keys had let his brown hair grow long since the trial; he looked like a slightly morose Samwise Gamgee. In contrast, Leiderman faintly buzzed. Wearing a gray windowpane Armani suit and a gray tie with an ornate yellow pattern, his curly hair slicked back, he mingled with local television reporters. He fiddled with his laptop. He joked with Segal.

“I don’t get nervous before a hearing,” Leiderman said. “I stand in the shower talking to myself. By the time I get out, I’m calm as shit.”

He was feeling optimistic. In the weeks leading up to sentencing, Leiderman had become convinced that they were “in the hunt for a halfway house and an extreme load of community service”: that is, no jail time. He had pulled all kinds of comps — comparable cases from which to argue for sentencing uniformity — and found what he felt were far worse crimes that had been punished with very little or no incarceration. He had written most of an epic, 70-page sentencing memo, during which time he had “barely eaten or slept for days.”

The memo argued...well, it argued everything. Keys had been in Anonymous's ironically titled #internetfeds chatroom for journalistic reasons; indeed, Keys’ entire life was dedicated to the noble calling of journalism. Segal himself had said Keys’ actions were “not the crime of the century.” In 2010, when the hack took place, Keys may have been “swept up in a world marked by a groupthink of hacking madness.” “Sharpie,” the hacker who actually changed the Los Angeles Times article, hadn’t been charged with a crime. Previous “digital intrusions” on Tribune Company media, including the infamous 1987 Max Headroom TV signal hack, had been treated as silly pranks. Keys didn’t think the login credentials would work. The CFAA was “using horse and buggy laws to handle a jet plane society.” It was splatter painting as criminal defense.

By contrast, the government wrote a concise 12-page memo. It gave credit to Leiderman and Ekeland as “excellent attorneys” and recommended a five-year prison sentence, down from the “reasonable” 87 months recommended in a sealed pre-sentencing report written by two U.S. probation officers.

The Tribune Company had submitted a loss figure at trial of nearly $1 million, which had been cut in the pre-sentencing report to a still-staggering $249,956. Meanwhile, the number that the government proved at trial was a fraction of that, $13,000. Early in the sentencing, Judge Mueller ruled that she would accept only the trial figure. The decision halved the sentencing range, with no statutory minimum. It appeared all the work Leiderman and Ekeland had done attacking the loss figures at trial had paid off. Leiderman looked ecstatic.

The low loss figure had changed the feeling in the courtroom. When Segal reiterated what the prosecution had said at trial — “this wasn’t mischief; this was a rage driven by profound narcissism” — there was a note of pleading in his voice. As he spoke, Leiderman hovered three feet away, hands clasped behind his back, staring benignly. He appeared to be somehow supervising the U.S. attorney.

And then Leiderman had the floor. As he had in his memo, he bundled as many arguments into his time as possible. In his high mid-Atlantic rasp, he pointed out that Keys hadn’t broken any laws before or since his indictment. Prosecutions such as this one had caused a lack of public trust in the government. Why had Keys been prosecuted? Was it because he was a journalist? Everyone shares passwords. The law was applied too inconsistently; the punishments didn’t fit the crimes.

Leiderman leaned forward, toward the judge, and his appeal grew personal. Keys had a bad childhood. And there would be some poetry in house arrest. “His grandmother was a prison guard for many years ... What better situation is there than having grandma there as an ex-prison guard?” Leiderman said. Judge Mueller, normally straight-faced, smiled broadly.

Finally, the defense attorney implored the judge to see Keys, and Anonymous, and hackers, in context, as part of the lava flow of technological change that is inherently countercultural, progress that the government inhibits only at a world-historical cost. He pulled out his iPhone and gestured to it.

“I don’t get nervous before a hearing. I stand in the shower talking to myself. By the time I get out, I’m calm as shit.”

“If Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had been phone phreaking with a blue box today,” Leiderman said, “they would have been prosecuted under the CFAA.”

The last argument, about the government stifling human progress, went too far. Matthew Keys may have been prosecuted under an unjust law, but he was by no means a sympathetic defendant, and his crimes were neither ones of conscience or techno-historical significance. Indeed, the juxtaposition between Leiderman’s sweeping rhetoric and his petty and unlikable client laid bare a simple fact: Opponents of the CFAA have yet to find their Edie Windsor, an unimpeachably righteous figure who comes to symbolize the harm done to innocent citizens by a bad, antiquated law. Or rather they did find that person, and he killed himself. Eventually, though, there will be another Aaron Swartz. There will be another person accused of violating the CFAA for whom an ideological argument compels people beyond the sphere of privacy experts and hackers, a person whose life and circumstances make the intellectual case against the law morally urgent. Perhaps Jay Leiderman will even be in the courtroom when that happens.

It didn’t happen in the courtroom in Sacramento. In her sentencing remarks, Judge Mueller turned one of Leiderman’s arguments against his client, admonishing Keys for abusing his position to harm the press he claimed to love. “I have no doubt Keys does understand the power of words and the notion that we take our debates public,” she said. “We fight words with words; we play fair.” She sentenced him to two years in prison and two years of probation.

Outside the courtroom, immediately following the sentence, Leiderman was uncharacteristically glum. “We walked in today facing an 87-month sentence and we walked out with 24. I suppose we should be heartened by that. But I’m not.” Though Leiderman and Ekeland had been saying for months that the case would be settled at appeal, and Keys would likely remain free pending that appeal, the day had briefly raised the possibility that their client wouldn’t serve time.

“Jay took it really hard,” Keys said a few days later. “He was really disappointed. He was, out of all of us, the most disappointed by it.”

There was a rushed press conference in the sunny plaza in front of the federal building. Keys had to drive his grandmother, his only family member who came to the hearing, the 45 minutes back to her home outside the city; she napped in the afternoons. Leiderman had a flight to catch back to Ventura in an hour — there had been some unexpected chicanery in the case of the blind man and the porn star.

But in front of the cameras, he seemed to have regained his good spirits. Somewhere from the half-moon of photographers and journalists who surrounded the men came a question for the attorney: How had he ever gotten Matthew Keys’ sentence reduced from a potential seven years to only 24 months?

Leiderman paused, considered.

“I’m an excellent lawyer!” he said, and grinned.•