Two years ago, as it prepared to build a new office on Manhattan’s West Side, the ad firm R/GA surveyed its 1,000-odd employees to ask what improvements they wanted made to their workplace. Number one was sit-stand desks. Easy enough. Number two was natural light: Some of R/GA’s New York employees had very little exposure to the sun.

That was trickier. Though 450 W. 33rd Street, a hulking brutalist ziggurat nicknamed the “Tyrell Building” for its unfortunate resemblance to the headquarters of the evil corporation in Blade Runner, was about to undergo an architectural facelift that would transform its facade from an opaque beige scowl into a clear glass grin, there was nothing to be done about the building’s floor plates, which were larger than football fields. The office was simply too big for everyone to sit near a window.

“It was a gutted, filthy, old warehouse,” said Julia Goldberg, R/GA’s senior vice president of global office services. “The lighting was terrible.”

The company had to figure out how to brighten up the place. Goldberg considered a commercial lighting system built by Philips, but it had no back end — no software to control the whole thing. For a 220,000-square-foot office, that was pretty important, if for no other reason than the time it would take to wander around turning on and off all the lights. Then, last June, the renovation team discovered Ketra, an LED lighting startup from Austin that promised some pretty big things.

The first was what Ketra calls “natural light”: white light sources that imperceptibly change their color and intensity throughout the day to mimic the lighting conditions outside. The second was an extreme degree of control. Ketra lights could be wirelessly grouped into zones of any number of lights that could all be separately adjusted via custom software on a wall panel, computer, or phone. The third was precision. Each Ketra bulb contained a patented sensor that measured its own color 360 times a minute to make sure the light being produced was the light being requested. Ketra was selling precisely measured, nature-approximating light, accessible throughout the massive office at the press of a button.

They sold the idea of light, not lighting.

It was exactly what Goldberg — who was under a mandate to help build an office that embodied R/GA’s recent rebrand as “an agency for the connected age” — wanted to hear. And it helped that the two Ketra employees who showed up to pitch her didn’t simply treat lighting as a utility or a mundane problem to be solved. Nav Sooch, the CEO, was a design-focused, Stanford-trained engineer who had already hit it big with a semiconductor company; Michael Heinemeier, the sales director, had previously worked on a light installation with the artist James Turrell, a MacArthur "genius." These were creative technologists preaching high-quality light as a convenient, aesthetically pleasing, and healthy lifestyle choice. They sold the idea of light, not lighting. R/GA was in.

Throughout the relatively short history of electric light, most improvements have been aimed at making light bulbs last longer or use less energy. Ketra is selling something different than dull efficiency: light as an object of beauty, light as a perk. For millennia, we made do with candles, torches, oil lamps, and the dim flickering of all manner of flames. Sure, the chandeliers at Versailles were nice, but the flames themselves were no different than what you’d light in the most modest hovel. Now technology has advanced to the point where illumination itself is a luxury good. What Ketra is selling is the idea that it can make your life better by giving you more control over how it is lit, in really minute detail — that electric light has contributed to making us unhealthier, and that electric light will make us healthy again.

Eighteen months and more than a million dollars of Ketra products later, the R/GA headquarters is a sight to behold, as cavernous as a hangar and as white and austere as a nun’s wimple. The space has accessorized terrifically with the humans inside it. On a recent afternoon, top-knotted men ordered lattes from an on-site Brooklyn Roasting Company. Women in black beanies, black sweaters, and black Nikes glided under dozens of massive projection screens displaying the agency’s work. And lining the ceilings, 2,000 white fixtures held 8,837 white Ketra lamps, casting cool, crisp white light worthy of an Apple ad on all the industry below.

450 W. 33rd Street is the biggest project the seven-year-old Ketra has ever finished, but it won’t be for long. It’s currently working on a new 300,000-square-foot headquarters for Stripe, the $5 billion payments startup. And Stripe marks the latest in a run of successes for Ketra, which has seemingly come out of nowhere in the past two years to light the spaces of some of the world’s biggest startups, trendiest businesses, and most august cultural institutions: Apple, Facebook (where it lights the Facebook Live studio in New York), Google, Vice, Eataly, the upscale salad chain Sweetgreen, the Art Institute of Chicago. (And, oh! BuzzFeed.) Meanwhile, R/GA, which runs its own consulting business, has started recommending the lights to its corporate clients. Recent converts include what Julia Goldberg would only refer to as “a well-known apparel company” (R/GA famously counts Nike as a client), as well as a “large hotelier” and Sheikh Mohammed of Dubai.

Ketra has positioned itself to illuminate our affluent, healthy, wired, and well-cultured future in part by being as chameleonic as its LEDs, which, in addition to emulating the sun, can turn millions of colors. To architectural lighting designers, the finicky aficionados of the lighting world, they comprise a creative tool kit par excellence. To facilities bosses with blank slates and enormous budgets, like Julia Goldberg, they are highly customizable, networkable, energy-saving conveniences. And to a crop of health-focused businesses — and tech companies eager to tout how lavishly they take care of their employees — they are wellness orbs, radiating futuristic vim.

But who really needs them? Being all things to all people doesn’t come cheap. A single Ketra bulb costs about $100. (That’s a lot for an LED: The Sweethome’s recommended bulb sells at $20 for four.) It’s even more considering the context of a gadget world that produces inexpensive and reasonably good knockoffs faster than ever, not to mention an LED industry with a built-in existential crisis — the bulbs last so long that selling their replacements isn’t necessarily good business. Nav Sooch is fond of saying that his company has invented a new category of product. And there’s no question Ketra has built a bleeding-edge light source and a sophisticated way to control it. But before you can sell millions of dollars of high-tech lighting to some of the world’s biggest companies, you have to convince them that there is a very big problem with their light.

It is the sad fate of artificial lighting to be a historical invention that most people only notice when it isn’t working. Ever since the advent and spread of modern incandescent lighting in the first half of the 20th century — a wonder enabling untold advances in every field of contemporary human endeavor — people basically think of their lightbulbs only when they burn out, or when it’s too dim to read, or too bright to take off their clothes.

“Everyone thinks light just happens,” said Sean O’Connor, a Los Angeles architectural lighting designer. “People just expect there to be light everywhere they go.”

“Everyone thinks light just happens,” said Sean O’Connor, a Los Angeles architectural lighting designer. “People just expect there to be light everywhere they go.”

If public awareness of lighting has nudged up a smidge over the past 10 years, it’s because of 2007 federal regulations requiring more efficient bulbs. So consumers made the change from traditional incandescents, which had been the standard for more than a century — and it was a pain. At first we switched to more efficient incandescents and compact fluorescent lamps, the ones that look like little curled pigtails. But CFLs can be hard to dim, contain mercury, and give off harsh, antiseptic light. People hated them. And now they’re dying: Earlier this year, GE announced that it would stop manufacturing and selling CFLs in the US.

That left LEDs, which produce white light either by mixing red, green, and blue or by slathering a yellow phosphor over a blue LED. Once prohibitively expensive and of highly varying quality, LEDs in recent years have plunged in cost and generally give off light that’s not all that far off, quality-wise, from daylight or incandescent light. They’re the present and the future of lighting, a $15 billion industry in 2014 that is on pace to exceed $21 billion by 2019.

But the LED industry faces its own day of reckoning. As J.B. MacKinnon has written, LEDs last so long that they undermine the traditional “planned obsolescence” business model of incandescents. How can companies maintain their profit margins when people only need to buy their $5 products every 15 years? Three of the huge players in the industry — GE, Philips, and Osram — have responded by spinning off part or all of their lighting businesses in the face of likely declining revenue. If people only care about light when their bulbs burn out, and if their bulbs almost never burn out, won’t people just stop thinking about light?

Maybe, unless companies like Ketra can define new ways that our lights aren’t working.

One afternoon in 2009 — long before affordable and high-quality LEDs could be bought at Home Depot — David Knapp accompanied his wife to a lighting store in Austin. The couple were building a new house, and he was more or less tagging along in case she picked out something he really hated. As Knapp wandered to the back of the showroom, he saw some lights that he thought looked odd and familiar, like light-emitting diodes.

Knapp knew LEDs. He had sold his first company, which pioneered the use of LED fiber optics to network multimedia devices in cars, in 2005. Now in his late forties and with time on his hands, he was intrigued.

“Yeah, they suck,” the salesperson told him. “We don’t recommend them.”

The clerk went on to explain that LEDs were bad at rendering colors and were marred by a whole range of issues related to color control (they were too bright and harsh), dimming (they didn’t, or did erratically), and aging (they changed color over time).

“I’d like to buy one of every one of those that you have,” Knapp responded.

That night, Knapp went home with a bundle of LED lights, where he “tore them apart, and started investigating why they were not the ideal solution. How do you address that? That’s what we spent the next six to eight years doing.” Knapp recruited Horace Ho, with whom he had built his first company, and together they invested more than $5 million of their own money into solving the problem.

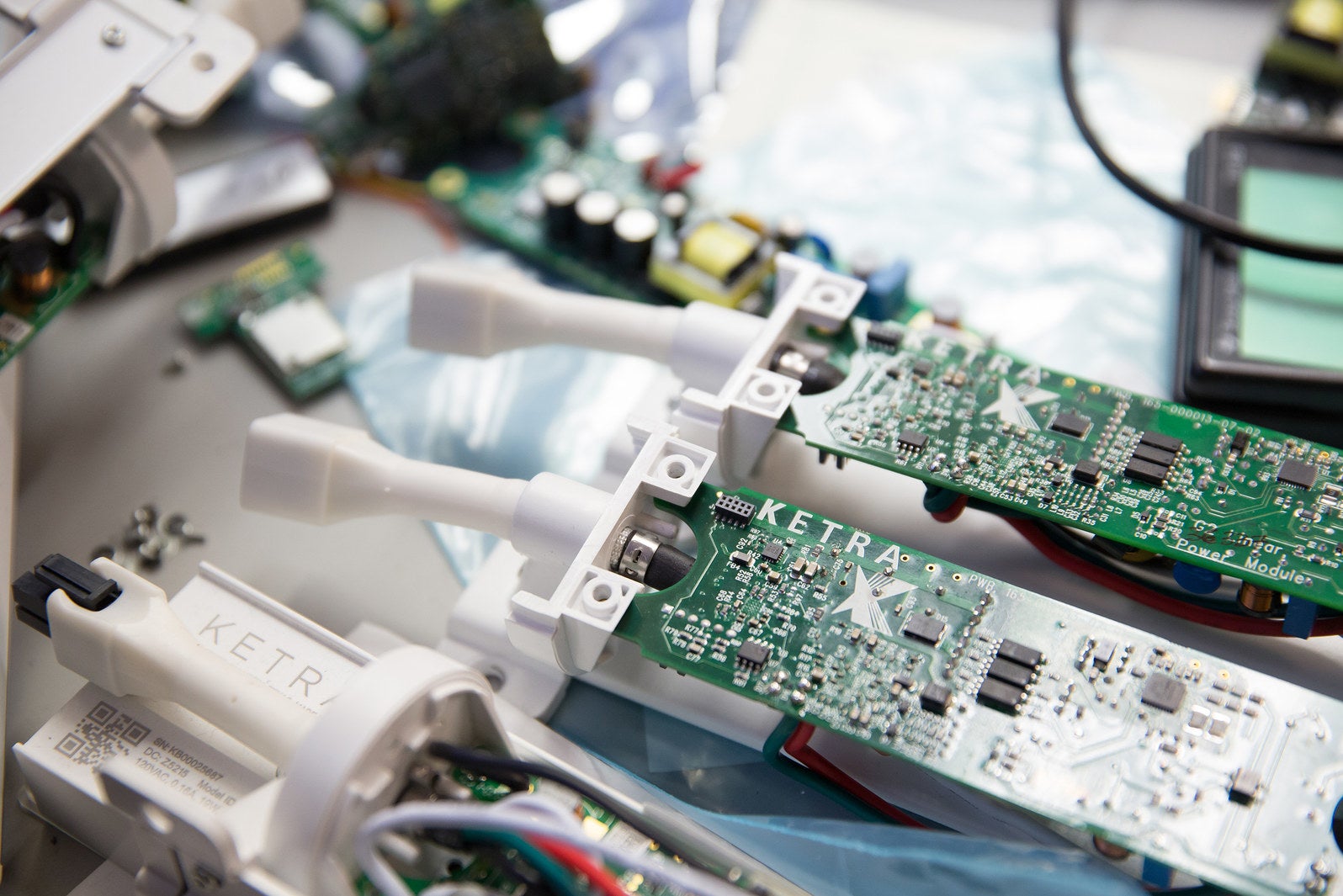

Their solution was, basically, a self-conscious LED — one that never stops analyzing the light that it produces. At the heart of Ketra’s tech is an LED chip capable of temperature-optical feedback, which senses heat and color output in real time and adjusts itself according to that data. Knapp’s early prototypes were on 12-inch printed circuit boards as big as laptops, but the results were encouraging enough to attract investors, including Nav Sooch, who had known Knapp and Ho since their days as young engineers. Sooch had made millions in the ’90s and early 2000s founding Silicon Labs, an Austin-based semiconductor company.

In 2012, Sooch traveled with Knapp to Korea and China to meet with major lighting manufacturers to try to sell them the Ketra chip. “They asked us questions about how they would turn that into a system,” Sooch said. It was, he thought, as if Elon Musk had taken the Tesla battery to Honda and they'd asked him how to make a car out of it. Philosophically, the big lighting companies didn’t get it, and practically, they weren’t set up to make processors; why waste time waiting?

“If we’re going to sell a chip to these big lighting folks, what do we make, a dollar or two per chip?” Knapp said. “We came back and were like, 'These guys don’t know what they’re doing, and we have to build the whole thing.'”

As Ketra expanded (it now employees 85 people) and began to design actual light sources, it solicited the interest of professional light obsessives, people who draw up elaborate specifications to ensure spaces are lit just so. In early 2013, Tom Hamilton, Ketra’s head of marketing, showed an early mockup — a big white translucent globe with the Ketra chip inside — to Sean O’Connor, the architectural lighting designer who does high-end retail, hospitality (think the St. Regis Aspen and the Beverly Hills Hotel), and residential projects. The advent of LEDs, inconsistent and unreliable, had made his job much more complicated and stressful.

“When we do an LED project, before we can write the specifications, we have to see samples from everybody to see if it does what it says it does. Historically, it doesn’t,” O’Connor said. “Everything is fiction until you try it.” It was as if an architect couldn’t be sure that a steel beam was the length they had ordered until they saw it in person.

Ketra, even with its goofy globe, promised what O’Connor regarded as “the holy grail” for LED architectural lighting: flexibility and standards. That is, an LED that dimmed like an incandescent, could shift between different kinds of white light while maintaining a high rendering quality, and did it every time, right out of the box. No other LED product on the market that did dynamic white — such as the popular Philips Hue, which O’Connor dismissed as “a consumer toy” — had the special chip inside ensuring consistent color temperature.

“It's very easy to use an LED just to sense 'is there light there or no?' but to sense the color and the intensity to get that level of information — I don’t know of anybody else who could do it,” said Maury Wright, the editor-in-chief of LEDs Magazine. “Hue says, 'What’s the difference if it’s a little more or a little less red?' For professional products, you want light matching exactly in terms of spectral energy.”

Winning over skeptics got Ketra in the door with an entire universe of places that depend on rigorously exact light: upscale restaurants, stores, and galleries. In early 2015, another architectural lighting designer suggested Ketra to David Thurm, the Art Institute of Chicago’s chief operating officer. Thurm had been trying to find LEDs to light his masterworks for years, but every time he gathered the curators together to run a test, they left unsatisfied.

“We would get funny results,” Thurm said. “We easily went through 10 LED manufacturers.” And even if the light rendered a painting well, it might be untunable and change the color of the wall. Thurm said he had heard of other major art museums repainting their walls to deal with the problem.

The Art Institute has the world’s largest collection of Monet’s paintings of haystacks, the impressionist’s famous studies of light and time. Thurm set up a viewing of the paintings lit by Ketra, with the museum’s director, curators, and conservation staff. They were astonished.

“We could tune it to a place where the paintings looked beautiful,” Thurm said. “We’re very fussy about this stuff. And everything we were getting from incandescent, we were now getting from LED.”

Ketra had won over the connoisseurs, who discern shades in white light with the same subtlety as oenophiles pick out notes in red wine. But as a lot of drinkers can tell you, you don’t need to spend a lot to drink pretty good wine. And in the years Ketra was building an incredibly complex LED to standardize tunable white light, the huge LED manufacturers were improving the consistency of their products through brute-force testing and economies of scale.

“Most of the LED makers have such good data behind their products,” said Wright. “Even though you aren’t getting real feedback, you can pretty much take their specs that show how that LED is going to change over time and build that into the product.”

That may not be acceptable for the Tiffanys and the Art Institutes of the world, but it is good enough for almost every consumer who just wants to switch out their old bulbs. And then you’re back to forgetting about light.

That’s why Ketra — along with its competitors — is trying to create new categories of light, or even trying to suggest new problems with your lights that you didn’t know you had, so you’ll buy a new class of products that you eventually can’t live without.

The first problem the lighting industry wants to sell you the fix to is that your lights are dumb: They don’t talk to each other, you can’t control them remotely, and they can’t do all sorts of cool things like turn on when you come into the room or alert you when there is unanticipated movement in your house. Technology analysts have long thought LED retrofits to be the Trojan horse of the Internet of Things, the vast network of internet-connected home devices that is so far most notable for enabling a botnet that took down big chunks of the internet in October.

And lighting companies like Cree, Philips, and Ketra have built software that works with devices like occupancy sensors and daylight harvesters (energy-saving sensors that measure ambient light) to scale up or scale down light depending on whether a room has people in it and how much ambient light it’s receiving. The appeal of such a system is obvious in an office; in an apartment or a small house, slightly less so. More prosaic Internet of Things controls are already common in smart LEDs like Philips Hue, although, as one reviewer wrote, for now, “The main reason to try smart bulbs is that they’re fun.” In other words, a toy in the mass consumer market.

Still, in a huge corporate setting like R/GA, which divvied its 8,000 Ketras into 110 zones of various sizes, this granular control is impressive. Julia Goldberg and five trusted associates can control these zones independently with a handy app on their phones. Why so many zones? Sixty small white daylight sensors hang at odd intervals, feeding Ketra brain boxes data about ambient light; different zones need different light at different times based on their position in the building. And some jobs are special. Video editors like it darker. HR, for some reason, likes it a little brighter.

The second problem Ketra and others would like to convince you of: Light might be making you unhealthy. Look around and you can find bad light being blamed for everything from cancer to obesity, from diabetes to depression.

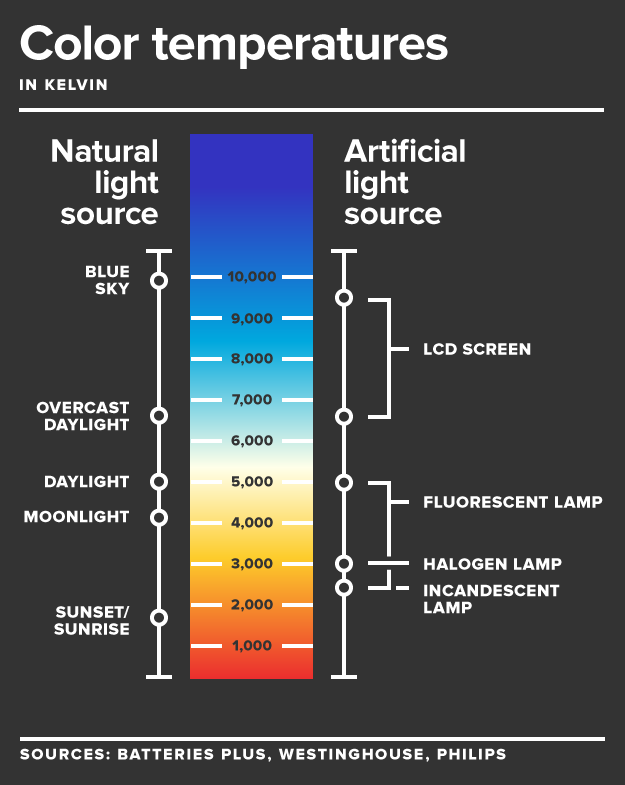

Most of these scary claims come out of nascent science around the connections between light and sleep. Studies have shown that exposure to blue light during the day suppresses the production of melatonin, the sleep-regulating hormone that our bodies make more of at night. That’s the idea behind Night Shift, the function in newer versions of iOS that turns iPhone and iPad screens warmer shades of yellow and orange at night. (“We do Night Shift, but on a building-wide scale,” said Sooch, Ketra's CEO.) A recent study by researchers at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Lighting Research Center found, unsurprisingly, that office workers got more exposure to sunlight in summer than in winter, and reported more and better sleep. The study concluded, “Strategies to increase circadian light exposures in buildings should be a consideration in architectural design.”

Still, the research is much too early for a company like Ketra to make any big claims about the health benefit of their lights — the FDA doesn’t even regulate the light boxes that some people buy to mitigate seasonal affective disorder, let alone LED startups. And it’s certainly too early for Ketra to say that its circadian lighting is better at regulating melatonin than any other LED that bills itself as “circadian,” even if it is more sophisticated. (An architectural lighting designer who asked not to be named said that most of Ketra’s “tunable white” competitors that tout circadian benefits simply jump directly between two settings at opposite ends of the color temperature table rather than shifting smoothly from one end to the other, like the sun does.)

“Lighting companies need to be very careful if they say that they have a health benefit,” said Philip Smallwood, director of LED and lighting research at Strategies Unlimited, an LED market research firm. “That opens them up to litigation. Not all bodies react the same way.”

Instead, like dietary supplements and “natural” foods, Ketra can fuzzily appeal to consumer sentiment around wellness. Honeybrains, a new café on a chichi stretch of lower Manhattan, bills itself as a “food experience where passion for people, food, and flavor combine to support your well-being.” In addition to antioxidant- and omega-3-rich foods, the café also sells T-shirts and $199 “brain sensing” headbands that help you meditate. And the whole thing is lit on Ketra’s circadian cycle, 30 different light conditions, or “scenes,” that go from cool and bright at midday to warm and soft at night.

With its story of disrupting a hidebound industry, Ketra can also appeal to tech companies, which, conscious of the long and sedentary hours its employees work — and competitive over 10x programmers — have invested in elaborate wellness programs. For example, as part of a “wow factor” renovation designed to “help retain staff and recruit prospective employees," the cybersecurity firm Symantec installed color-shifting lighting “to complement natural circadian rhythms.”

And the last thing Ketra wants you to buy? Your light makes you look like shit. In a culture growing more and more sophisticated about online self-presentation, people are getting smarter and more particular about the way they look in different lighting conditions. LuMee, the light-up LED phone case endorsed by Kim Kardashian West, the high priestess of social media aesthetics, promises to help users “look perfect.”

“We’re like Photoshop for real life.”

“The secret to a good selfie is definitely lighting,” she wrote on her website.

Ketra imagines spaces that go one step further, in which people move through rooms set to light that flatters different skin tones at different times of day.

“We think every space you walk around in should make you look better,” said Sooch.

“We’re like Photoshop for real life,” said Michael Heinemeier, director of sales.

The “natural light” Ketra wants consumers to want ultimately looks like the simultaneous solution to those three problems: customizable, constantly flattering light that does what we want when we want it to, and makes us at the very least feel healthier. In Ketra’s ideal future, its light works in much the same way as a salad from Sweetgreen or an Equinox gym membership does — as a premium version of a commodity that expresses something unique about the identity of the consumer, whether that consumer is a wealthy individual or a jewelry store or a tech company worth billions.

Whether anyone truly needs to pay a premium for Ketra’s “natural light” is hardly pertinent to the pitch; both Sweetgreen and Panera sell lettuce and dressing, but try convincing the young professionals lined up for the former that the latter is just as good. Is it so hard to imagine a future in which these same people, or groups of people, have their own lighting presets that make them feel comfortable, or creative, or hale, or attractive, or intimidating — their best selves?

One afternoon in early 2016, Heinemeier was programming some lights Ketra had just installed at Vice’s Brooklyn headquarters. When the Ketra network first discovers a new light, the device cycles from a yellowish white to a pastel blue. As dozens of Ketra lights turned blue, a Vice director walked into the room with a Blood-affiliated Compton rapper and his entourage. They were not pleased.

Thinking fast, Heinemeier asked the group for a moment. Then he turned all the lights red.

“Everyone laughed,” he said.

But, you know, still: $100 for a lightbulb. Is the problem Ketra pitches — that your current lights don’t make you feel a little healthier and make you look a little better while keeping their color rigidly correct — really a $100 problem for anyone except the rich, the connoisseurs, and that westerly behemoth of an industry that finds a problem most everywhere it looks?

Well, that figure is a bit misleading. You can’t actually buy a single Ketra bulb off the shelf yet, though Sooch and co. say they’re working on it. Right now the people getting Ketra in their homes are the kind of people with money to spend on a lighting designer — like Sooch and his wife, former ABC News anchor Whitney Casey, who, as you might expect, lit their Southampton house with Ketra.

Sooch said that the cost of Ketra averages around $10 a square foot, which is in the mainstream of what people pay for lighting plus a control system. It’s true that office buildings are all required today to have control systems. That said, not every office building or store — let alone every home — can start from scratch.

“Right now it’s a premium product,” said Sean O’Connor. “It’s hard to mix and match it in an environment that isn’t completely Ketra and make the value proposition make sense.”

Sooch insists the cost will come down, and again points to Tesla as an analogy. “They started with a sports car that very few people could afford,” he said. “And now they make the Model 3, which is mainstream.”

One way that could happen is if Ketra, which holds 30-odd patents, licenses or sells their chip to a big lighting company. And maybe selling lighting as a lifestyle, rather than a utility, is one way that the industry’s major players approach the end of planned obsolescence.

“Ketra has the most incredible tech on the planet when it comes to lighting,” said O’Connor, “but I’ve always wanted Ketra to license or sell to other folks so it’s not just five or six lamps that they have on offer.”

Indeed, while Ketra may have solved a massive technical problem, it’s not clear that the sociocultural one it also purports to fix is urgent enough to convince people outside of Silicon Valley and trendy retail to shell out for it. Then again, maybe it doesn’t have to. Maybe the product, or something like it, will make its way from ad agencies and tech giants and upscale salad chains into the homes of their employees. And maybe, when the price comes down, the kind of light Ketra has to sell will become the kind of light everyone takes for granted, and the sight of cheap, dumb LEDs will make us feel the subliminal dread that the Sweetgreen devotee stifles in their breast while hurrying past a Panera.

On a recent gray afternoon at R/GA headquarters, dingy nimbostratus clouds drooped over the Hudson River, blocking the sunset behind the Jersey City skyline. In the elevator, leaving work, a video editor paused to consider the highly advanced light under which he worked. “It’s cool,” he said. “I don’t even notice it anymore." ●