In January 2008, something sharp — mostly likely an errant ship anchor — sliced into two underwater cables in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Egypt, near Alexandria. Egypt lost 80% of its internet capacity. But the effects were hardly limited to that country. Slowdowns were reported across Asia. Saudi Arabia lost 40% of its national network. Even Bangladesh, some 3,700 miles away, lost a full third of its connectivity.

Why did just two cuts lead to such widespread disruption? The classic, and least expensive, way to route internet from South Asia to Europe is via a vast system of submarine fiber optics running from the southern coast of France through the Mediterranean, into the Red Sea via the Suez, and finally out into the Indian Ocean and points beyond. Many of the countries hurt the most by the cuts relied heavily on this path, with only light redundancy coming in from the east — East Asia and beyond the Pacific Ocean, North America — to protect against an event like this.

And shipping accidents are hardly the only hazards associated with running fiber-optic cable through the Middle East. It's a very real possibility that an act of war — a bombing or a firefight — in one of the most unstable regions in the world could literally disrupt bulk financial transactions running between skyscrapers in London and Abu Dhabi.

The economic consequences of such an outage are obvious and devastating, and they don't only hurt big banks. Take just India, with its booming virtual outsourcing sector, enormously reliant on dependable internet. By some reports, 60 million people in India were affected by the 2008 disruption.

Jim Cowie, then the head of research and development at Renesys, an internet intelligence company, was taking notes. "It's very embarrassing to have to explain to stock markets and banks that the internet is out and will be out for weeks," Cowie said.

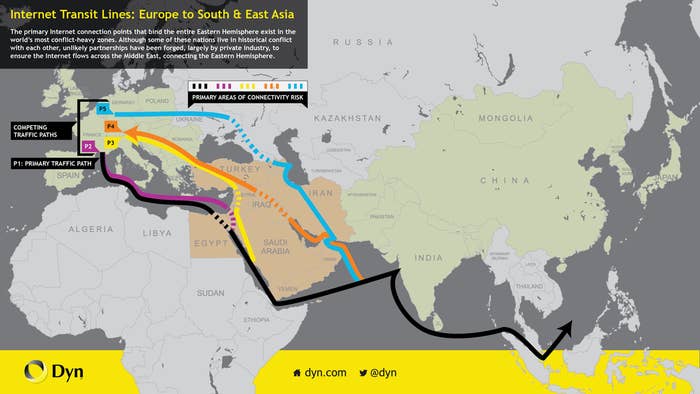

In the wake of the 2008 disruption, companies on both ends of the Mediterranean route began clamoring for redundancy, or the creation of alternative network links from Europe to Asia. And over the past half-decade, a series of enormous European and Asian telecom consortia have done just that, building four new overland fiber-optic pathways to link Europe to the financial hubs of the Persian Gulf and the booming economies of South Asia.

The new pathways are displayed on the map above, which was made by Dyn, the New Hampshire company that manages traffic for some of the biggest sites on the internet (and that acquired Renesys in May). The new routes are faster than the submarine route — up to 20 milliseconds faster from the Persian Gulf to London, a hugely significant amount of time when it comes to automated financial transactions — and also costlier. But ISPs, banks, and other major companies will readily pay a premium to diversify the source of their internet service and ensure that they aren't vulnerable to future outages.

Still, reaching South Asia from Europe by land requires traveling through the Middle East, and none of the new networks can completely avoid regions marked by the kind of conflict that — in addition to every other kind of financial and human cost — could produce a future outage.

Take the JADI network (displayed in the top image as yellow), which runs for nearly 1,600 miles from Istanbul to Jeddah. Less than a year after JADI traffic became available for purchase, Syria broke out in civil war, and the cable, which runs through Aleppo, has sustained chronic damage, disrupting the network.

The stakes of these new networks are high, with their own very present, very real dangers: Syrian network technicians whom Cowie describes as "heroic" literally "roll trucks in the middle of a firefight to repair the damage."

That's the most dramatic example. But the other cable paths all face their own challenges. The network represented above in purple is, according to Cowie, in service, though it bypasses the Suez via Israel, a country rapidly descending into violent conflict. The path running through Iraq in orange has experienced difficulties in "coordination and agreement," according to Cowie, due to a lack of cooperation between the autonomous Kurdish authorities and their Arab counterparts.

Even the so-called EPEG (Europe-Persian Express Gateway), which has managed to avoid major disruptions despite running through volatile parts of the Caucasus and which Cowie calls "the biggest success story" on the map, passes through a newly turbulent eastern Ukraine (and, notably, leaders who have not been shy to threaten other kinds of pipeline disruption).

Ultimately, the only way for corporate and institutional interests to make sure that they don't suffer outages in the future is to make the sources of internet they buy access to as diverse as possible. That way no single act of man or nature proves so catastrophic as to repeat the disastrous disruptions of 2008.

Or, as Cowie said, "The remedy for all of these is politically neutral": More cable.