Until he lost an eye, April 15 was a good day for Joseph Cavins.

The 63-year-old Orange, California, family therapist saw a full slate of clients. It was two days before tax day, so he caught up on records from his practice. After work, he hung out with some friends. And he wound his day down in the usual way: by playing a game of solitaire on his computer while he enjoyed a few drags off one of his e-cigarettes, which he had been using nearly every day for two years.

At around 10:30 p.m., as Cavins turned his head toward a nearby bookcase, he heard a “very loud bang” and felt as if he had been struck in the face by a hockey stick. A fire smoldered on his desk. He held his hands to his face and discovered that “there was a lot of blood and fluid coming out.” He began to scream: “No! No!” He couldn’t see out of his left eye.

Cavins smothered the fire and woke his wife. At the hospital, doctors found that the explosion had caused extensive damage to his eyeball: Several cuts had pierced his iris and cornea, and they went all the way to the socket. The doctors recommended a surgical “evisceration”: the removal of the eye. Sitting in the emergency room, Cavins began to process what had happened: His vaporizer, the device he had bought as a “nice, clean way to get nicotine,” had exploded into his face.

He wasn’t alone. Across the country, defective e-cigarettes — the nicotine delivery machines that have taken over every strip mall and sidewalk, seemingly overnight — are creating hundreds of victims like Cavins, people whose lives are suddenly and horrifyingly changed when their devices blow up. They are people like Thomas Boes, whose vape exploded while he was driving outside San Diego and struck him with such force that two of the three teeth he lost lodged in his upper palate; Kenneth Barbero, whose exploding device ripped a hole in his tongue; and Marcus Forzani, a 17-year-old whose left leg was charred from his calf to his thigh after a vape battery exploded in his pocket. An unpublished FDA analysis found 66 reports of e-cigarette overheating, fires, and explosions in 2015 and the first month of 2016, a number the agency calls “an underestimate of actual events.”

Until very recently a totally unregulated $3.7 billion industry, e-cigarettes are widely expected to surpass traditional tobacco products in sales within the next decade. Responding to intense — if tempered — consumer demand and unencumbered by rules, hundreds of small distributors have over the past five years rushed devices, mostly imported from China, to market. Thousands of small stores have cropped up to sell them. According to a 2015 CDC survey, nearly 13% of Americans had tried an e-cigarette in their lifetime and there are more than 9 million adults who use e-cigs regularly; those numbers have almost surely gone up since.

The industry has grown so rapidly in part by claiming health benefits over traditional cigarette smoking, namely that it is safer to inhale the vapor produced by heating a nicotine solution than it is to inhale the 7,000 chemicals dispensed by a paper cigarette. Indeed, most of the concern and debate over e-cigarettes has focused on the relative merit of those claims.

Much less of the public debate has focused on the devices themselves, which have demonstrably maimed dozens, and probably maimed hundreds, including Cavins, Boes, and Barbero. Recently, though, personal injury lawyers across the country have started to take notice.

“The batteries are exploding due to an unclean manufacturing process at dirty, unsanitary facilities in China,” said Gregory Bentley, a California lawyer who represents 62 people who have been injured by exploding e-cigarettes. “That’s as a result of people trying to rush these products to the marketplace.” Because it’s nearly impossible to sue a Chinese manufacturer, Bentley and other plaintiffs' attorneys have focused on the American distributors and sellers who make money off of the devices. Bentley’s firm, Shernoff Bidart Echeverria Bentley, was the first to reach a verdict against a seller of e-cigarettes, in October of last year.

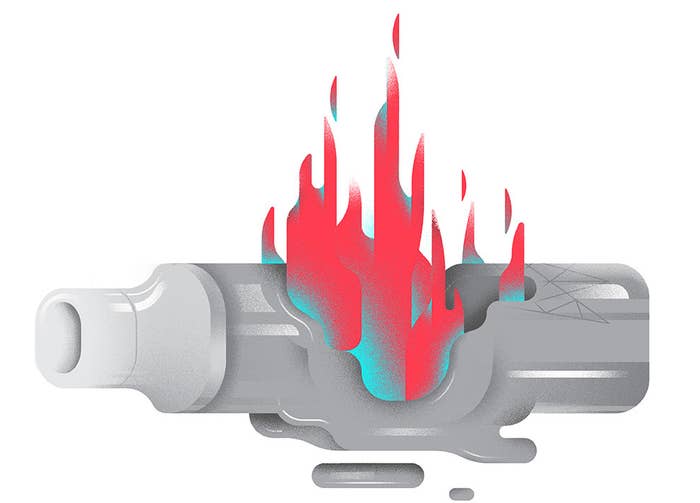

Bentley is correct that the direct cause of these explosions is an overheated lithium ion battery, but the science behind the trigger for these so-called thermal events is still something of a mystery. The first problem, and one reason lithium ion failures in e-cigs may be more dangerous than in, say, computers, is their shape. According to a 2014 report by the U.S. Fire Administration, the cylindrical design of e-cigs makes them particularly dangerous in the event of overheating: “As a result of the battery and container failure, one or the other, or both, can be propelled across the room like a bullet or small rocket.” That’s why, in both Cavins’ and Boes’ cases, the explosion turned the devices into projectiles.

But what causes the failure in the first place? According to Venkat Viswanathan, a professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon who studies lithium ion batteries, extremely low failure rates — somewhere between one in a million and one in a billion — make it difficult to determine.

“That’s the challenge of large numbers. It’s hard to prove,” said Viswanathan. “We would have to test a million cells and see what is going on. The only way to find out is to put a million products in the hands of consumers.”

Which is, more or less, what’s going on in the market today. That’s where Glen Stevick, a mechanical engineer and failure analyst at Berkeley Engineering and Research (BEAR), comes in: He’s the Sherlock Holmes of lithium ion batteries, running postmortems on explosions like the one that partially blinded Joseph Cavins. BEAR has investigated more than two dozen such cases. According to Stevick, the real problem is that many of the e-cigarettes on the market today lack the electronics, both in the devices themselves and in the chargers, to prevent both dangerously high-voltage charging and equally dangerous low-voltage discharge. Each of these states — too high and too low — can ultimately lead to short-circuiting, overheating, and, ultimately, explosion.

Better preventative measures would likely stop hot batteries from ever getting to the point where a thermal event reaches “runway.” These include circuits that regulate charging; a stiff, hollow core on the inside of the battery that sloughs off extra energy; and a switch that causes the battery to lose conductivity at certain levels of heat. Of course, those preventative measures cost money. The e-cig business in America has been defined by its prolificacy: A 2014 report found that there were 466 brands of e-cigarettes on the market, a number that was increasing by an average of 10.5 brands a month. Many of these companies are small and have to skimp on quality to compete with larger manufacturers.

“Some companies get really good batteries at a cheap price,” said Viswanathan. “Smaller-scale device makers don’t have the same luxury. They have to lean on low-quality suppliers.”

"The FDA has taken a good first step, but it’s clearly not enough."

Earlier this month, the FDA announced a long-awaited set of rules that extended its authority to all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes. Crucially, the new federal rules include not just the tobacco solution, but components and parts as well. These rules will require e-cigarette makers to submit premarket tobacco applications to the agency, a process that the FDA estimates costs “in the low hundreds of thousands of dollars.” According to Michael Felberbaum, an FDA press officer, the agency recommends that the applications include information about under- or over-voltage lockout protections.

“The FDA has taken a good first step, but it’s clearly not enough,” said Bentley, Cavins’ lawyer. “I believe the industry needs to put testing protocols and manufacturing guidelines in place for chargers. And to what extent they will get in and look at the factories? That’s the most important process.”

While American regulators won’t be setting foot inside Chinese factories anytime soon, the new rules may nevertheless indirectly put a stop to the creation of substandard batteries. By forcing smaller companies, which won’t be able to bear the costs of approval and higher-quality components, out of the nascent space, the FDA may eliminate cheaper batteries from the market. In other words, twin financial pressures — litigation on one end and regulation on the other — may ultimately end the problem of exploding e-cigs and make the batteries inside as safe as those in laptops and automobiles. While some have called the regulations “a gift to Big Tobacco,” which will be able to bear easily the costs of premarket approval, standardizing safer batteries would be an indisputable upside of industry consolidation.

“We’re making cars with 8,000 cell batteries and they’re safe,” said Viswanathan. “In most cases e-cigarettes have one cell.”

In the meantime, there will continue to be fires and explosions, at least until a two-year FDA grace period for e-cig companies runs its course. That means likely hundreds more Americans dealing with the aftermath of life-changing injuries. That means hundreds more people like Joseph Cavins — who has quit nicotine products — who will continue to serve as a reminder that unregulated product crazes come with consequences. “I’m not coping as well as I would have liked,” Cavins said of losing his eye. “But I’ve given myself permission to do the best I can.”