Days after the election, Donald Trump called Pat Caddell from his office in New York to revel in his victory. “He wanted me to understand how well he did,” Caddell remembers. “You win the presidency, you have a right to crow.” Caddell should know: He helped launch Washington outsider Jimmy Carter to the presidency in 1976, and he elevated anti-establishment candidates like George McGovern, Gary Hart, Jerry Brown, and Ross Perot to surprising successes exploiting populist discontent. He was described in 1987 as “the living American with the most direct experience in Presidential campaigns, except for one, Richard Nixon.”

But a public quarrel with then-presidential candidate Joe Biden solidified Caddell’s reputation for being incurably disagreeable. He spent the ensuing 30 years largely in the political wilderness, gradually turning more and more conservative until he became a cable news hack trading on his days as a Democrat. “I don’t know what produced the Caddell we have now — this bitter, angry character who is a hatchet man for Fox,” says Hendrik Hertzberg, a Carter administration speechwriter and longtime New Yorker writer.

The hatchet man now has influence he hasn’t in decades. He is a longtime friend of Trump’s and acted as an informal adviser throughout the election. Trump routinely called Caddell during the campaign to compliment something Caddell had said on television or dispute any criticisms leveled his way. Caddell visited Trump Tower during the campaign and took a bag of Trump ties offered by the candidate. (“They’re $100 ties — what the fuck, why wouldn’t I?”)

Caddell is similarly close with Trump’s chief strategist Steve Bannon, who invited him a few years ago to write for Breitbart. He also has a fan in Roger Stone, a loyal adviser to Trump. Caddell, 66, speaks less passionately about these connections and his renewed influence than he does about his ideas. He loves his ideas. “This election was just like 1828: They were gonna take their country back,” he says over lunch at a Southern BBQ chain in Charleston, where he’s lived for a decade. As Caddell speaks, he pounds his fist on the lunch table, rattling his plate of chili and beef on bread. “The country is in revolt, and the media and the establishment are running a real risk because they refuse to recognize, even today, the legitimate dissent of the American people, and that is an outrage.”

“I have a story that is the real story of the last several years, none of which is of interest to anyone. Nobody pays attention to this stuff, because they don’t want to know.”

Outrage is Caddell’s default emotion. He is outraged that America is being plundered by a Washington elite he once personified. He is outraged that the media and politicians are conspiring to hold the country down (he is prone to conspiracy theories in his personal life, too — he complains to me that having to travel to upstate New York for his granddaughter's recital is “some kind of gambit” designed to financially exploit him). And, most of all, he is outraged that he wasn’t listened to for almost three decades. “I have a story that is the real story of the last several years, none of which is of interest to anyone,” he tells me. “Nobody pays attention to this stuff, because they don’t want to know.”

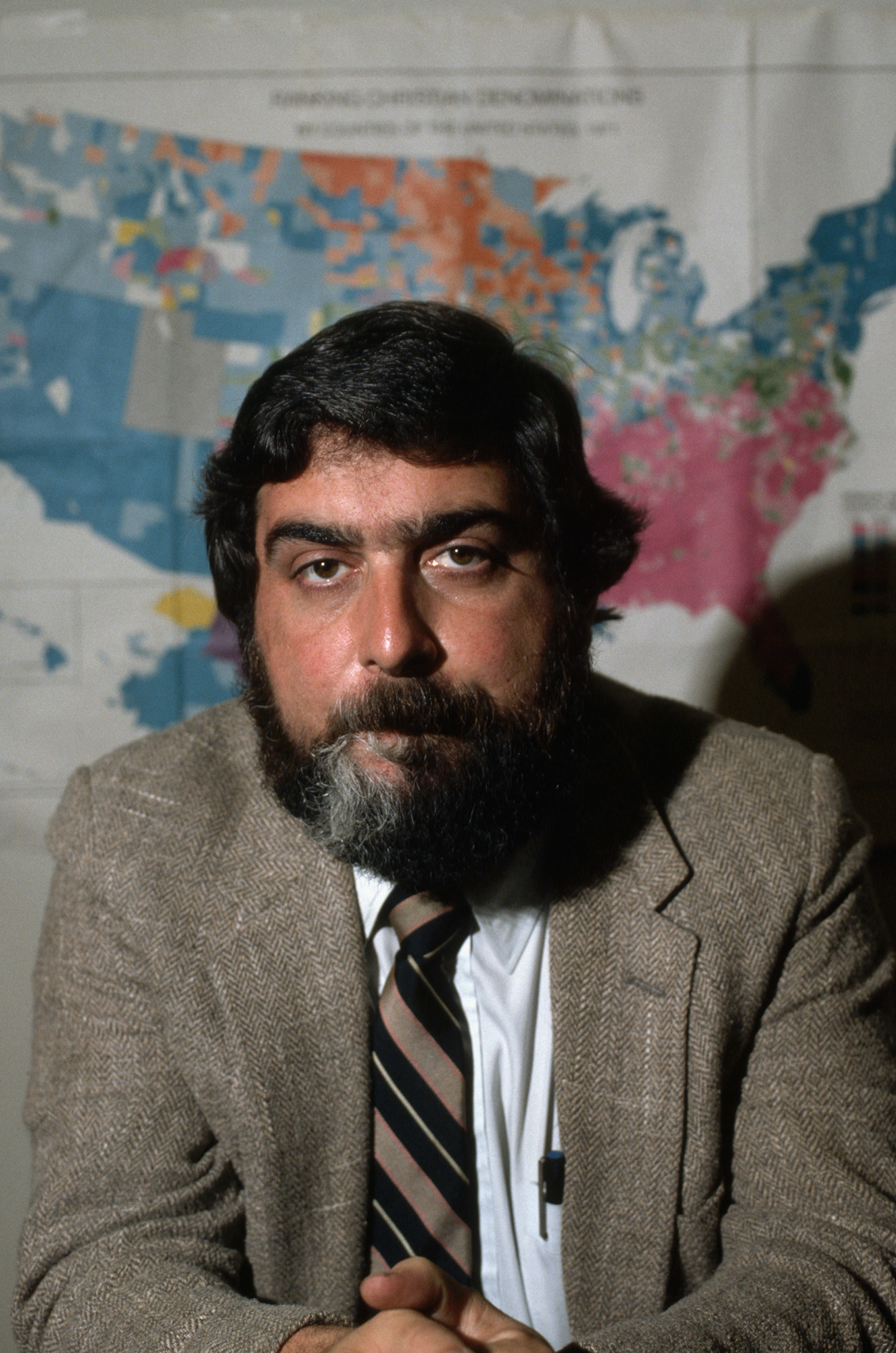

With his neatly combed black hair, he looks like an aging boxer who came out of retirement for one last bout, got knocked around in the ring, and just showered up. Yet Caddell’s mind remains remarkable. He speaks in memos. You can almost see his brain classifying and interpreting surveys of the American electorate. He quotes — from memory — lines from his hero Bobby Kennedy, and from books by historians C. Vann Woodward and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. He speaks of polls the way homicide detectives speak of crime scenes. “I always try and figure out what they’re trying to tell me, what I can intuit from the data, what they’re saying,” he says.

They have long told him that Americans are alienated from their political system. Caddell became famous for guiding little-known one-term Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter to the presidency in 1976 on a wave of public disillusionment with national institutions post–Watergate and Vietnam. He worked for candidates who were outsiders, underdog politicians who upended Beltway thinking by bashing the Beltway. “His genius was to figure out how to first attract this alienated vote and then turn it into an antiestablishment campaign,” analyst Bill Schneider once said.

Caddell’s alienated electorate reached its apex with Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. The white people who despise a Washington that once worked for them lost faith in an America that once supported them and feel betrayed by a country they sacrificed for. “Pat in 1979 was a prophet seeing what’s going on now,” says Hertzberg. “The crisis of confidence in American institutions has bubbled ever since then and seems to have boiled over with Trump.”

Though Caddell is unlikely to join the Trump administration, he knows he is being heard in the White House. He knows that he pioneered the strategies Trump used to catapult himself into the presidency. He knows that, in his own small way, he made Donald Trump possible. And he thinks you would know that too if the Washington establishment didn’t hate him. In a 1979 memo, Caddell warned with eerie prescience that if alienation continued, “America could yield to a man on horseback” — an authoritarian leader whom desperate citizens empower. Now the man on horseback has arrived, but instead of working to defeat the autocrat, Caddell has saddled up to join him.

As a high school senior in the spring of 1968, Caddell questioned citizens in white, working-class Jacksonville, Florida, about the upcoming presidential election. This amateur polling for a class project occurred when America seemed to be collapsing: Riots happened all over the country, students occupied university administration buildings, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, crime skyrocketed, and Americans realized, despite terrible losses, that they were not going to win in Vietnam.

Residents told Caddell they liked two seemingly opposite candidates: Bobby Kennedy and George Wallace. Kennedy was a liberal icon, preaching racial harmony, outreach to the poor, and ending the war. George Wallace, as observers have noted, shares much in common with Trump — inciting violence at his racially charged rallies, scapegoating distant elites and intellectuals, and reveling in being ostracized by respectable politicians.

The enthusiasm for men espousing contrasting policies flummoxed Caddell. Rather than sticking to simple yes-or-no questions, Caddell flouted contemporary polling practice and asked voters why they were for either Kennedy or Wallace. “I would argue with them,” he laughs over lunch. “I was making it up as I was going along.” Caddell’s laugh is rare — he is usually intense and often angry. His black eyebrows are thick and expressive, curling far above his eyes. He informs the restaurant staff twice that I am here to interview him, but he prefers explaining contemporary politics to rehashing his past. He indulges me, though, even as he is annoyed by the server screwing up his beverage order. “They have a thing about not wanting to give you lemons here,” he complains, before telling the waitress that he “could use some more ice” in his water. She brings him a glass of ice and he scoops some into his hand and talks about the opinions he heard in Jacksonville that resonate 50 years later.

People were alienated from regular politics. They hated the way the system was being run, they told him. And they thought that perhaps an honest, tough-guy outsider could fix it. Forget the policies — Kennedy and Wallace could shake up the system, and that was enough. “But the country still believed in the fundamentals,” Caddell explains. "It was wrong and broken; it could be fixed. But there wasn’t fundamental questioning of the concepts."

Caddell had discovered both a new method of canvassing public opinion and an anti-establishment sentiment that would become a dominant force in American politics. Coming from generations of Democrats, Caddell worried that working-class white disaffection would destroy the party. He studied the Southern vote at Harvard, starting a polling firm while he was a sophomore. Nothing else like it existed at the time — comprehensive analysis backed by actual numbers.

Even then, Caddell was known for being disheveled. One memorable contemporary description compared him to "a figure out of Dostoyevsky, a large man hunched inside an unpressed wardrobe, a shambling gait, and a brambly, dark beard.” Another account said he was “just barely civilized — sloppy, rude, forgetful, tempestuous. It was as if he was raised by wolves.”

In 1971, a friend introduced Caddell to Gary Hart, the young campaign manager of South Dakota Sen. George McGovern’s long-shot presidential campaign. “It was the only campaign I had no enemies,” he says. “Everyone loved me because I was the child.” Caddell advised McGovern to increase his populist rhetoric and tour factories instead of obsessing about the Vietnam War. McGovern shocked everyone by finishing a strong second in the New Hampshire primary in 1972, showing he could garner support from more than just college students. “He didn’t win as just the anti-war candidate,” says Caddell. “He won because he was against the establishment, against the war, and on alienation."

Walking from the restaurant to his orange Jeep, I ask Caddell what Trump should do to restore Americans’ faith in their country beyond attacking the establishment. He has little to say, mumbling about campaign finance reform. Trump lied and said he was a wholly self-funded presidential candidate, and therefore singularly incorruptible, but even then he never offered solutions to Washington corruption beyond electing him — and has since filled his cabinet with the kinds of CEOs and bankers he'd railed against. His White House counsel led efforts to destroy what few restrictions do exist on money in politics. McGovern, conversely, genuinely eschewed plutocracy — his campaign was funded largely on $20 donations.

With Caddell’s guidance, McGovern piled up primary victories and eventually garnered the Democratic nomination — a stunning upset. Caddell was suddenly a national star at 21, attending classes at Harvard in the mornings and holding press conferences for national media in the afternoons. At one point, Harvard informed him that he wouldn’t graduate unless he passed the customary swimming test. And so, rather than return from the campaign trail, Caddell swam in a California hotel pool and had his strokes judged by Theodore White, who was on the Harvard Board of Overseers, and Hunter S. Thompson.

Though McGovern lost the presidential election, Caddell met a different benefactor while on the campaign. Traveling through Atlanta, he stayed at the mansion of Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter. Carter and Caddell stayed up late into the evening talking on kitchen counters, drinking beer and discussing Caddell’s Harvard thesis. A Southerner who was progressive on racial issues could be irresistible to the country, Caddell believed. No Southerner had been elected president since Zachary Taylor in 1848, and he was a war hero. Carter was completing a single-term governorship of a small state. But Caddell was supremely confident in his abilities — he had already helped make one improbable Democratic nominee.

Two years later, Caddell visited Carter’s peanut farm in Plains, Georgia. Carter was the perfect man for the job. While deeply religious, with a missionary zeal, he didn’t have ironclad political convictions: His signature program as governor was the nonthreatening issue of government reorganization. Crucially, he was also a farmer who had never lived in Washington. Caddell knew that voters who were convinced Washington was a cesspool would see Carter as uncorrupted rather than unqualified.

Carter was noncommittal on policy specifics, someone voters could project their hopes onto.

There was another reason for their inattention to policy solutions that could fix America: They didn't really have any. Caddell convinced Carter to run as an honest individual, a Southerner who could heal racial divisions because he was progressive on race, to restore Americans’ faith in themselves. The candidate’s neutral slogans, “I’ll never tell a lie” and “A government as good as its people,” resonated enough with a country that had grown increasingly cynical following the violence and cultural upheaval of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Carter was noncommittal on policy specifics, someone voters could project their hopes onto, with a vagueness so pronounced that the campaign eventually felt compelled to produce television ads explaining that Carter did indeed have positions.

Carter’s opponent, incumbent President Gerald Ford, understood Caddell. “On an institutional basis he is a generation ahead of most other candidates,” read a Ford campaign memo. “No one has yet devised a system for protecting a GOP incumbent from the Caddell-style alienation attack.”

No one did. “You know why Jimmy Carter is going to be president?” Carter’s campaign manager predicted. “Because of Pat Caddell — it's all because of Pat Caddell.” The prediction proved accurate. Just 25 and already wealthy, Caddell moved to Georgetown and became a Washington celebrity, with profiles in the New York Times, Time, and even People (“the whiz kid pollster who plays good news-bad news with the president”). He dated Hugh Hefner’s daughter, brought Lauren Bacall to the inaugural ball, and drove a gold Mercedes. His office featured a silk-screen print of Carter done by Andy Warhol. “I believed the world was made of strawberry shortcake and cherries — I mean, what could be better?” Caddell says now about those days. Driving through Charleston, he complains about the middling weather and points to parts of the city that have been rebuilt since a hurricane. “I could have gotten an amazing deal if I bought a house here 10 years ago,” he says.

The years from the end of World War II to the late 1960s marked the last era when white Americans were confident their kids would be better off than they were. In 1964, 64% of Americans polled by the National Election Study believed the government was “run for the benefit of all the people.” But just 10 years later, amid riots, crime, Vietnam, assassinations, and so much more, that number was down by 25%. Faith in the government’s ability solve national problems similarly plummeted.

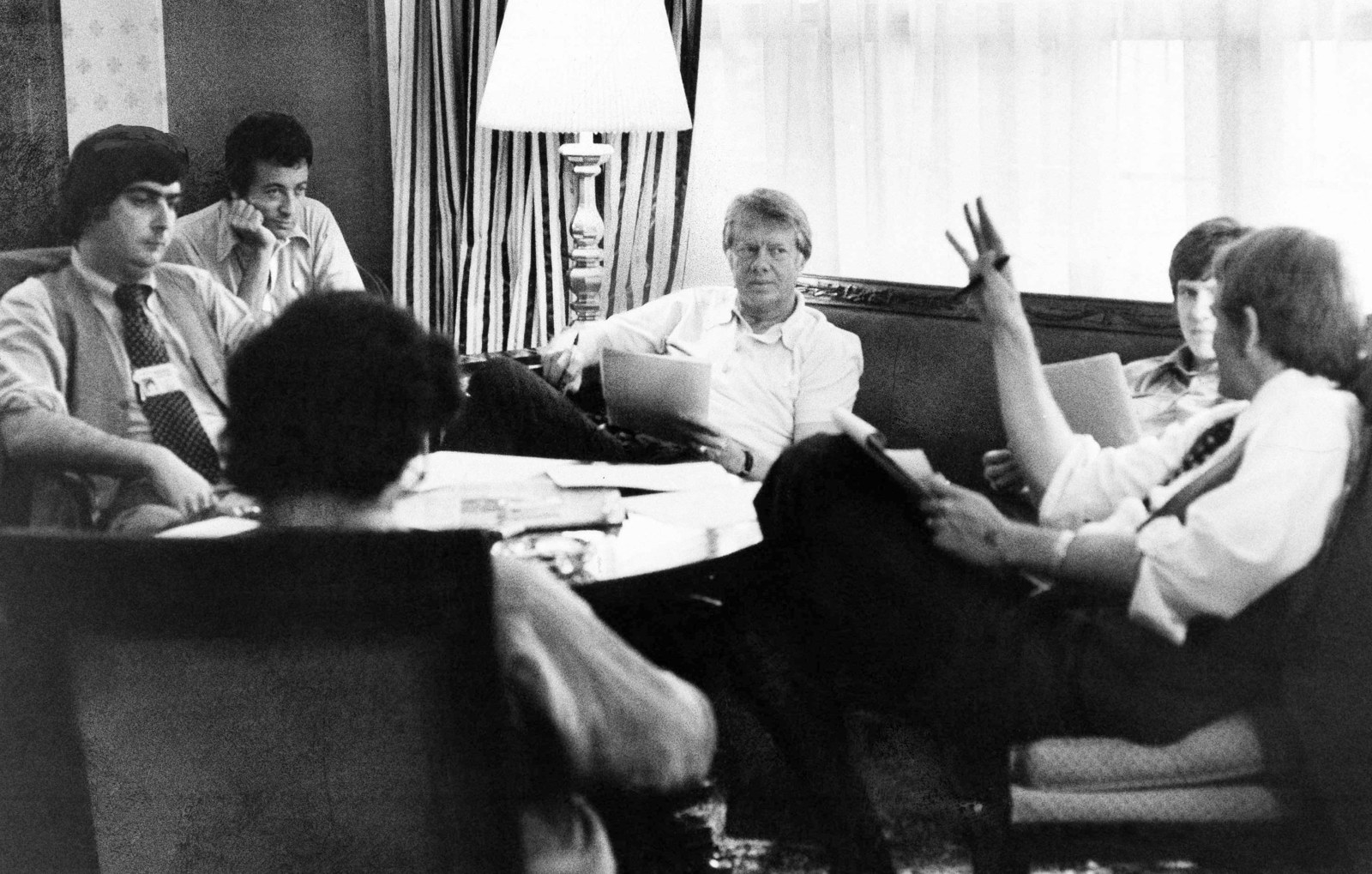

The times called for bold leadership, but Caddell’s post-election polling showed 50% of the country still didn’t even know newly minted President Carter’s positions. Seeing an opening, Caddell submitted a 10,000-word, 62-page memo that was, in the words of Sidney Blumenthal, “one of the essential documents of modern American politics.”

In his memo, Caddell outlined a method for Carter to be a successful president in an era defined by cynicism and disaffection. “Americans have no real expectation that the government is willing or able to solve the country’s problems,” he wrote. Rather than solve those problems with concrete policy, Caddell advised Carter to make cosmetic, symbolic changes. Carter must, the memo dictated, portray himself as “different from other politicians, not part of the establishment” and embrace unsubstantial but popular symbolic acts such as fireside chats, town hall meetings, and question periods with the public, to be seen as a “practical anti-politician.”

Carter began wearing sweaters instead of suits and opened phone lines to ordinary citizens. He soon acted on other superficial Caddell suggestions from the memo designed to boost his immediate popularity: enacting an agency for consumer affairs, instituting new budgeting strategies, and cutting down on staff limo rides. But by early 1979, Carter was suffering in national esteem, as soaring oil prices, high inflation and high unemployment, the fall of Iran to Islamists, and deteriorating relations with the Soviet Union took an enormous, ongoing toll on his presidency. Sweaters and town halls couldn’t erase complex national problems.

Caddell believed Carter’s problem was far greater than any specific policy. His problem was that Americans had lost faith in America. One day, as Caddell was flipping through Time magazine, he found an article on “disastermania.” It was a eureka moment. Americans saw their challenges not as distinct phenomena that could be overcome; they were signs of a disintegrating nation on the verge of complete meltdown.

Caddell saw his chance to turn Carter into an instrument of greatness, to make him into JFK or Bobby Kennedy reincarnated. He began working furiously. He dictated notes to his assistant as he paced around the room. He was so full of ideas that he wouldn’t finish one thought before he was on to the next one, leaving his assistant typing furiously. Caddell wasn’t writing an ordinary speech memo — he was writing a manifesto.

The result was 75 pages, featuring the momentous title “Of Crisis and Opportunity.” (It was known among disconcerted White House staffers as “Apocalypse Now,” the name of the movie Caddell had helped market.) The memo said that America might collapse as France had before the Nazi army in 1940: “This crisis threatens the political and social fabric of the nation.” Caddell quoted Keynes, de Tocqueville, books on leadership, and newspaper articles to make his point. Never in American history had an adviser delivered to a president a document so simultaneously grandiose, disturbing, and concerned with intangible problems.

Carter tested out some of Caddell’s ideas in speeches, telling audiences that Americans were fearful and disillusioned and that he didn’t have all the answers. The remarks were well-received for their candor. And so on July 15, 1979, Carter delivered the Caddell-influenced remarks that defined his presidency, in what became known as “The Malaise Speech.” “It’s clear that the true problems of our nation are much deeper than gasoline lines or energy shortages — deeper, even, than inflation or recession,” Carter said forcefully, jabbing his hand at the Oval Office desk he spoke from, as 100 million Americans watched at home. America was suffering a “crisis of confidence,” he said, a phrase Caddell lifted from Bobby Kennedy. “It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will.”

Though remembered as symbolizing Carter’s ineffectualness, the address was initially a huge success. His approval rating jumped 11% instantly. White House operators couldn’t manage the flood of calls supporting Carter’s sentiment. More letters poured in than when Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon or when Nixon invaded Cambodia. “The speech struck a chord, just as Trump has,” says James Fallows, a former Carter administration speechwriter and longtime Atlantic writer. “The difference was that Carter was saying, ‘We have to be better.' Trump is saying, ‘Only I can save you.’”

Carter asked for the resignations of his entire cabinet after the speech, wanting a fresh start. Instead, he confused the public and began a downward spiral from which he never recovered. Beyond delivering a jeremiad, Caddell’s memo contained no meaningful recommendations, no ideas about what the president should actually do after giving the speech. “The question you’re asking — how do you deal with the alienation? — was what I realize was missing,” Caddell admits to me. “The Carter administration could never come to grips with it.” Neither could he.

What Caddell never realized is that by tapping into the alienation Americans felt — by exploiting it without resolving it — he was actually worsening the problem.

What Caddell never realized is that by tapping into the alienation Americans felt — by exploiting it without resolving it — he was actually worsening the problem. He raised expectations that were impossible to fulfill, creating more alienated citizens, more people whose hopes were raised and then unrealized.

Still, he remained a key adviser during the 1980 presidential election campaign. But Caddell’s astonishing ascent had taken a toll. He began each day of the campaign by using now-discredited primal scream therapy: In the shower, he would scream at his loudest, attempting to release frustration and anxieties. “That’s a period when I really should have gone and gotten some help in the sense of really working this out — I was so afraid of the stigma of doing so,” he said later.

Stories emerged about Caddell’s imperiousness: He had a terrible temper, disparaged colleagues to reporters, and was strangely self-righteous for a guy working for private clients — including the government of Saudi Arabia — while simultaneously advising a president. White House aides would go behind his back to get polls so they didn’t have to go through him. Said one of the Harvard classmates he still worked with: “When he would come up from Washington, most of the staff would figure out a way to have doctors’ appointments, sick mothers, or work elsewhere. When Pat was around, there would be explosions over the silliest things.” He left a sweater at a company house once, and he returned two weeks later to find it missing: “He went berserk, saying someone had stolen the sweater and nobody could leave the office until someone confessed.” Stories like this became more common in the following years.

I see glimpses of it when we meet for drinks in a Manhattan hotel lobby. He is in town for a taping of Hannity, and he is so furious at the city’s traffic that he has difficulty sitting down to talk. He is furious that the country is being robbed by Washington. And he is furious that journalists no longer call on him the way they used to. “Nobody’s knocking on my door,” he says, his eyes closing while he passionately makes a point. “It’s a threat for them to acknowledge that the country is against them. The country is in revolt.”

The 1980 election ruined Carter: He lost to conservative icon Ronald Reagan and Democrats lost seats in the House and the Senate. But the results seemed to validate Caddell’s theories. Independent candidate John Anderson did surprisingly well, since voters were disenchanted with Democrats and Republicans. Moreover, Caddell noticed that many voters supported the liberal Anderson until the last minute, when they opted for the conservative Reagan. It was Kennedy-Wallace all over again. And it showed that alienation in American politics wasn’t temporary or passé — it was a permanent feature of American life.

Following Carter’s loss, Mondale was the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination in 1984. But Caddell joined the campaign of his old friend Gary Hart, a Colorado senator running against him. Caddell disliked that Mondale had the support of unions and congressional Democrats — the establishment.

Caddell shared some polls with Hart showing room for an insurgent. This insurgent would have to present himself as a fresh face, willing to buck traditional Democratic Party thinking — and the party establishment. Caddell may have been a one-trick pony, but it was the horse to bet on. Acting on Caddell’s advice, Hart presented himself as a new, youthful voice running against the traditional Democratic Party insider. And, just like McGovern and Carter before him, he did far better than expected at the ballot box. Hart eventually lost to Mondale, but it was yet again an instance of the appeal of being a self-proclaimed outsider to growing segments of the American people.

By this time, Caddell had made enough enemies to be nearly run out of town. By telling powerful people they were corrupt, he was a traitor to his class. “I was threatening the entire order,” he says. But the reality was that Caddell had become so unpleasant that most people refused to work with him. "Losing wasn’t as bad a memory as having had to work with Pat Caddell,” one Hart campaign aide said.

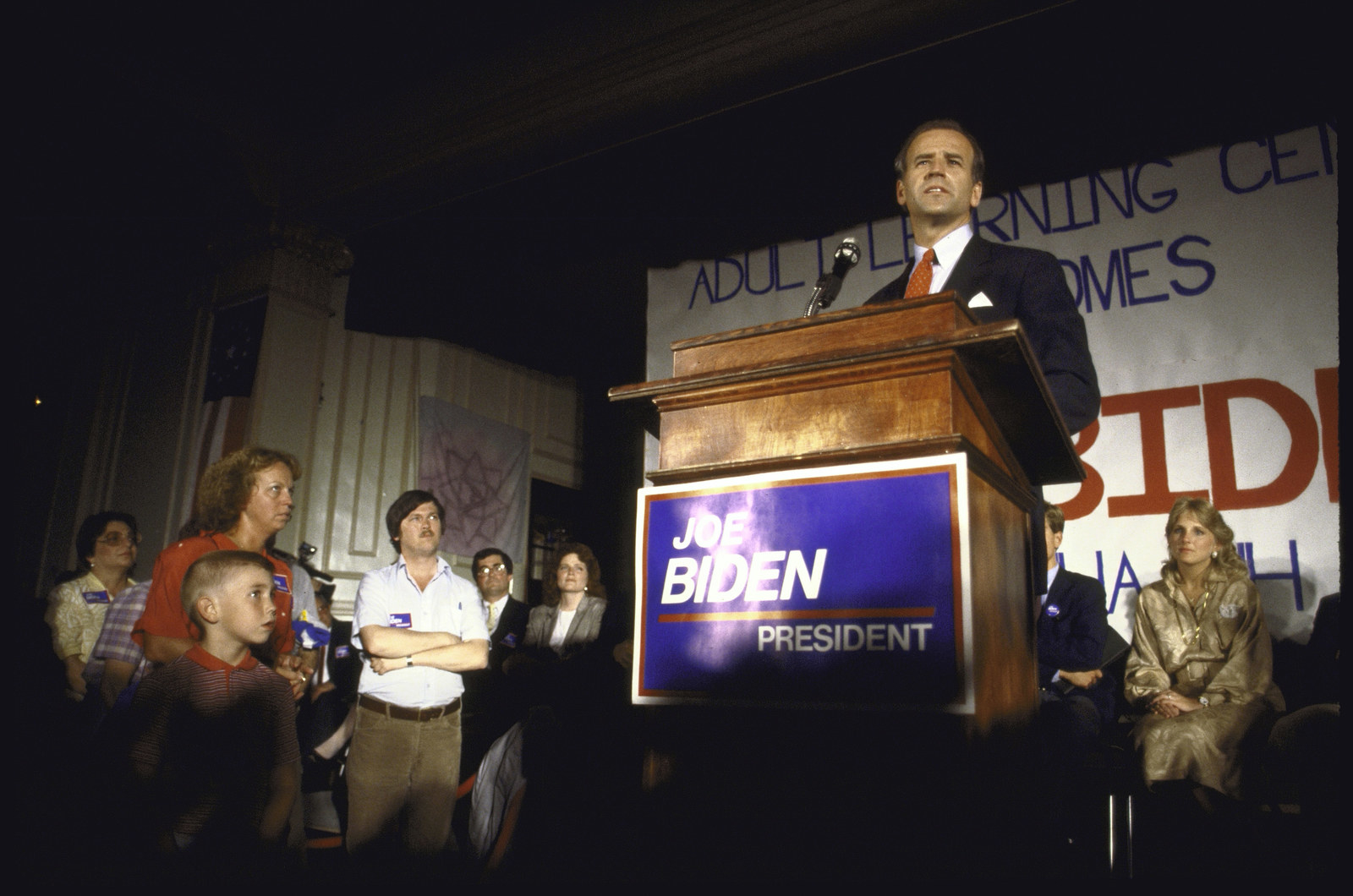

Caddell had one campaign left in him. Joe Biden and Caddell were close, cooperating on Biden’s initial senatorial bid in 1972, where a 21-year-old Caddell helped the 29-year-old deliver a stunning upset victory by just over 3,100 votes. Caddell meshed with Biden in a way he had not even with Carter. “Sometimes it’s hard to know where Pat’s thinking stops and mine begins,” Biden said at the time. The two had been close friends for some 16 years, and 1988 finally seemed to be the year Caddell could make Biden president, as he had with Carter. Caddell helped write Biden’s official announcement speech.

Biden’s campaign began well — until a New York Times reporter noted that Biden had stolen much of his speech from a British Labor politician. A reporter from the San Jose Mercury-News dug through Biden’s speeches from earlier that year and found that one contained phrases stolen verbatim from Bobby Kennedy’s, in 1968. The speech was written by Caddell. Television networks showed the speech given by Biden and Kennedy on a split screen, to devastating effect. Biden was found to have lifted other lines from both John and Robert Kennedy, and from Hubert Humphrey. The revelations were particularly damaging because they reinforced the notion, prevalent then, that Biden wasn’t his own man. He was Caddell’s.

Biden’s advisers were telling him it was over, but Caddell wasn’t having it. On one occasion, he burst into a staff meeting and screamed, “You’re a lynch mob, trying to kill my candidate. Fuck you.” Finally, members of Biden’s circle met at Biden’s home and advised him to drop out. Caddell, who wasn’t in attendance, called every 15 minutes to argue otherwise. He told one of the advisers that he had “no right to give my candidate advice.” He told Biden’s press spokesman, “You people have formed a vigilante party to get my candidate out of the race.” Finally, he called and Biden’s brother wouldn’t put the candidate on the phone.

A week after he dropped out, Biden released a statement through a spokesman: “The senator wants it to be known that he has no animosity toward Pat Caddell, but that he has ended his relationship with him.” The relationship never recovered. “I’m not comfortable yet to talk about it,” Caddell tells me, 30 years after it happened.

Caddell moved to California. He had a comfortable life, driving around in a blue 1966 Mustang convertible and consulting for movies. But, try as he might, he couldn’t resist the game, intermittently advising Ross Perot’s 1992 presidential campaign. Involvement with Perot, a businessman running as an independent, marked a turning point for Caddell. Perot was something of a proto-Trump. He had charisma, an erratic temperament, and no governing experience. He had become famous for being a billionaire and being involved with Vietnam POWs.

Unlike anyone Caddell had worked for before, Perot was something of a conservative. Many of his positions — cutting Social Security and spending, opposing free trade and gun control — were counter to long-held Democratic orthodoxy. But Perot came from outside the traditional two-party structure and railed against Washington, and that was enough for Caddell. He called Perot a “genius and a genuine patriot.”

Perot finished with nearly 19% of the vote, the most of any third-party candidate of the 20th century besides Teddy Roosevelt. Caddell saw that Perot’s success was not a unique situation but rather a sign of permanent social discontent now reshaping the traditional political system. He said that David Duke and Vermont’s Bernie Sanders — one the head of the KKK and the other a Jewish socialist, both with rising profiles in national politics — were “supping out of the same pot.”

When a reporter asked if he believed America was indeed in decline, Caddell responded affirmatively: “You don’t have to convince the American people of that — they now know it.” Long before others saw it, Caddell said that the country was losing the sense that “we leave our children a better America, and more opportunity. You kill that idea and you will kill this country.”

The ascension of Bill Clinton to the White House in 1992 meant Caddell was shut out of Democratic circles — during the campaign for the party nomination, he had advised Clinton’s primary rival, Jerry Brown. And, not coincidentally, around the same time, he began his anti-Democrat shtick. “My friends are more corrupt than my enemies,” he said. Washington was “corrupt to the core,” destroyed by the “political, economic and media elite.” If it was, that situation was equally true when he lived there and pioneered new forms of corporate-political consulting.

He and his partner Douglas Schoen, who worked for the Clintons in the past, became known as “the Fox News Democrats” — men who were once Democrats and still identified as such but espoused quintessential Republican views on television. Caddell was a vicious critic of Bill Clinton and Al Gore, ultimately donating to Green Party candidate Ralph Nader in the 2000 election. When Gore revoked his concession to George W. Bush once voting irregularities became evident in November 2000, Caddell said that the Democratic Party “has become no longer a party of principles, but has been hijacked by a confederacy of gangsters who need to take power by whatever means and whatever canards they can.”

Throughout the 2000s, Caddell shed whatever Democratic connections he had left. He detested the 9/11 Commission, he hated the New York Times, and he reviled John Kerry’s presidential campaign, led by his former business partners, whom he described as “political crypto-gangsters who have taken over the heart and soul of the Democratic Party in Washington," adding that "their job is [to] hold on to power and hold on to money.”

Caddell persistently predicted gloom for the Democrats. He said in 2006 that running against the Iraq War would be disastrous — but the party won big in the midterms and then elected anti-war candidate Barack Obama in 2008. Caddell and Schoen advised Obama in the Washington Post in 2010 not to run for re-election, since such a gesture of goodwill would end partisan gridlock in Washington.

Simply put, Caddell became an ordinary Fox News hack. His identification as a veteran Democrat credentialed him with viewers who didn’t know any better, but his views were orthodox movement conservatism. Obama was a “raging narcissist who ha[d] no grip on reality,” he said. Choked up with emotion on Fox News, sitting beside Ann Coulter, he said the media was “a fundamental threat to American democracy and the enemies of the American people” for ignoring Hillary Clinton’s treachery in Benghazi. It is tough to keep Caddell on track with any subject besides the perfidy of the media, the Democratic Party, and establishment Republicans. One day he phones me to say he’ll be able to meet with me the following week, and also that “no one wants to know anything” about how the country is being destroyed from within by the media.

In the summer of 2012, Caddell solidified his transition to right-wing pundit by becoming a regular contributor to Bannon's Breitbart. “He happens to be quite a student of history on this stuff,” Caddell says of Bannon's attitudes towards alienation, populism, and nationalism. Caddell offered him advice throughout Trump’s campaign on how to appeal to independents and disaffected Democrats. Bannon reportedly considered bringing on Caddell in a formal campaign role, but an offer never materialized.

"For three years no one has paid attention to what I’ve said. The country rose up.”

Unsurprisingly, Caddell’s remarks on Fox and talk radio during the campaign were Trump-friendly fare. He argued that the media was executing “a coup d’état” against American democracy by ignoring Hillary Clinton’s email scandal. Polls were rigged, electing Clinton would turn America into a Third World country, and “globalism” was a serious threat to the nation. “Reporters are like cockroaches,” he even said, on Breitbart radio. Still a registered Democrat, he voted for Bernie Sanders in the South Carolina primary. Though Sanders was a democratic socialist with a philosophy and record completely at odds with the crony-capitalist Trump, the Democratic Party establishment opposed him, and that was enough for Caddell.

Caddell was ripe for Trump’s picking. With his contempt for the political order and disdain for policy details, Trump exploited sentiments that Caddell presciently became preoccupied with 40 years ago. Trump’s biggest supporters are the spiritual heirs of the Kennedy-Wallace supporters Caddell met knocking on doors in Florida in 1968: White men and women, angry because they thought America was one thing and realized it is another. Democrats betrayed them by embracing civil rights, and then Republicans tricked them into supporting oligarchy. For people of color and the educated, America now is a better place than it was in 1950. For working-class white people, it isn’t. They have been left behind, and they know it. Caddell was never one of them, being a political prodigy, but he has merged his grievances with theirs. Somehow the wealthy political consultant and the white working class have both been screwed.

The morning of the election, Caddell, virtually alone among pollsters, predicted a Trump victory. In an interview where he also concocted a fantasy of Clinton’s campaign engaging in widespread voter intimidation, he said that swing voters would turn out en masse for Trump. They did, and Trump should have thanked Caddell for his assistance.

“For three years no one has paid attention to what I’ve said,” Caddell says to me, speaking with Trump-like wounded pride. “The country rose up.” After one segment in autumn on his Fox show Political Insiders, Caddell received one of the many calls he got from Trump throughout the campaign. Caddell had been blasting the polls showing Hillary ahead, saying they were wrong and pollsters were conspiring to elect her. Caddell still had his mic on when Trump called him from his plane. He loved the segment, he told Caddell. Caddell smiles as he tells the story. ●