The crowd outside Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore was thousands strong by most estimates, and like always, Devin Allen was in the middle of the churn, hands on a camera, eyes coolly scanning, roving, while his heart drummed in his chest. He was a veteran protester, for causes of all stripes, but this march felt different. Bigger, yes, but also more charged. It was April 25, 2015, the first Saturday since the death of Freddie Gray, the young black man whose spine was severed while in police custody. Gray was only 25, a year younger than Allen at the time. And though they weren’t friends, Allen grew up near Sandtown-Winchester, the infamously poverty-wracked neighborhood on the city’s Westside where Gray lived.

“I know the girls yelling in that video,” Allen would recall later, referring to the cell phone footage of Gray’s arrest that inevitably emerged. It could easily have been him in those cuffs, his legs dragging behind him on the sidewalk.

The protests had been stirring peacefully since midweek, but a long, warm weekend day meant that more people, especially young people, had all afternoon to spend in the street, demanding that someone answer for Gray’s fate. As the marchers turned onto Howard Street, the main entranceway to downtown from I-95, Allen found himself between a group of black teenagers and some rowdy white Orioles fans who started shouting slurs. Then garbage started flying, and suddenly the most touristy section of Baltimore was a blur of tears, punches, and kicked-in car windows.

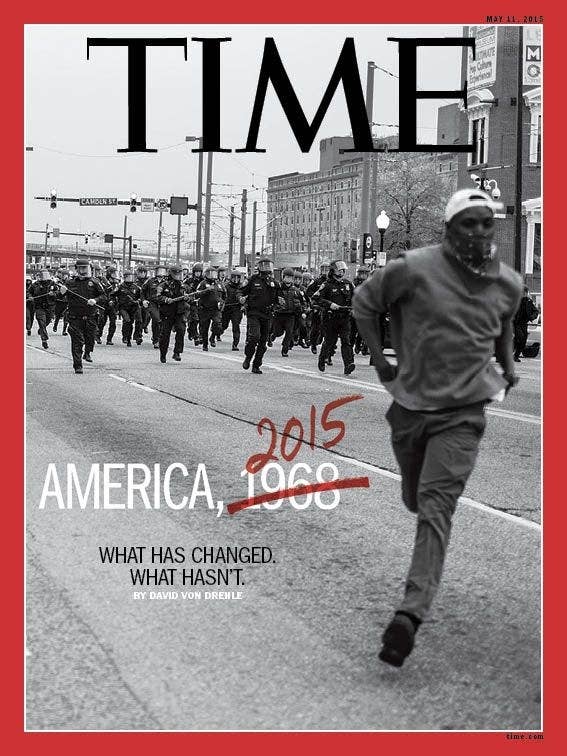

Minutes later, the marchers began fleeing a phalanx of combat-outfitted officers. Allen paused, aimed his camera, and spotted a young, solitary black man running from the police, his face obscured by a bandana. Allen posted the photo to Instagram almost immediately, and did the same for dozens of other shots as downtown spiraled into chaos throughout the afternoon and coming days, and shared by Beyoncé, Rihanna, Erykah Badu, and Black Thought. But none of his images amassed thousands of likes and hundreds of regrams and comments like this particular one, which he captioned “We are sick & tired.”

Over the next few few weeks, Baltimore was a media flashpoint around the world — the latest proof, in Time magazine’s calculation, that the United States was devolving back to the civil rights era. Following the initial protests, the editor of the magazine’s Lightbox photo blog interviewed Allen about his ongoing documentation of the uprising. The following week, Time fashioned Allen’s photo into an instantly iconic cover, adding the headline “America, 1968,” with the date scratched out and replaced with “2015.” Allen didn't know his shot made the cover until he saw it on Twitter. Overnight, the era of Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin had its own version of “The Soiling of Old Glory.”

Part of that Time cover’s power, as the magazine acknowledged, was its improbability. The photo wasn’t taken by an AP or newspaper staffer, but a local — only the third amateur to grace the the magazine’s cover in its 93-year history.

For many in and outside Baltimore, Devin Allen, 28, captured the defining image of a city in agony — maybe even the defining image of the Black Lives Matter moment — and his cultural coronation was swift: When Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom had a private meeting with Pope Francis to discuss “the power of images,” he included Allen’s in a collection of only 10 photos from around the world. Allen says he's donated 20 photographs, including the original Time shot, to the permanent collection at the Smithsonian’s newly opened National Museum of African American History & Culture. Oprah interviewed him.

With clout like that, Allen seemingly had a golden ticket to choose his next career move; he chose to join the sports-clothing behemoth Under Armour as a commercial photographer. The company is increasingly Baltimore’s signature brand, and it has not hesitated to capitalize on that fact; as of late summer 2016, Under Armour is set to receive $660 million in public funding for a new mixed-use corporate campus south of the Inner Harbor, despite the city’s perennial budgeting woes. And suffice it to say, the company doesn’t employ a lot of people from Sandtown-Winchester. But hiring the city’s best-known ascendant young artist was certainly a savvy move, and the position offered Allen something that photography, or any other job, hadn’t yet supplied: a stable income near the community he still wanted to serve.

“I’ve lost more than 20 friends,” he said. “Some of my friends have killed my other friends. At the end of the day, I wouldn’t put it past someone who’s jealous to try and kill me.”

Devin Allen’s journey embodies the perils and potential of viral artistic fame in an era of upheaval. Even if the stars do align and your work becomes the kind of thing that inspires bootleg T-shirts, there are few mentors or institutions to help artists sustain an actual career. As his profile grew and mainstream media attention moved away from Baltimore, Allen found that his greatest challenge was finding a way out of being merely “the Time guy.” And as a person who had cared about Baltimore’s struggling black population for years before the national media showed up, he still wanted his work to help his people in some way.

As the first anniversary of the uprising came up earlier this year, Baltimore was flush with celebrities and media crews in town for a commemorative “Unity March” on April 24. The mayoral primary race was drawing to a close, and every candidate was looking for community endorsements and photo ops. But Allen said, defiantly, “I’m a loner. My camera don’t snap for that.”

Instead, he spent that day far away from the crowds. He had a cousin who had just finished an 11-year prison sentence for robbing a drug dealer and needed new clothes, so Allen took him to the Under Armour factory store and used his employee discount. At night, he had his customary whiskey, neat, and thought about other confidantes, the ones whose birthdays he’d never celebrate again. Men like Sean Gamble, Chris Samuels, and dozens of others who have filled Baltimore’s morgues and police blotters for years.

“You on my mind dummy R.I.P. lil brova we miss you down here,” he tweeted a little after 10 p.m., along with a faded, unartful snapshot of James Cornish, one classmate who Allen had known since middle school. Cornish was killed in broad daylight, only a few days after he'd asked Allen for printed copies of the photographer's work. In the picture he was just a young man in a backwards hat and Big Lebowski T-shirt, holding a baby.

It would soon be April 25, the one-year anniversary of the image that changed Devin Allen’s life. A minute later, he tweeted again: “My pain run deeper than the ocean.”

In late July, Ericka Alston-Buck sat in the shadow of the Kids Safe Zone in Sandtown-Winchester. Under a pop-up tent in the parking lot, across the street from a cacophonous playground and a busy basketball court, her male co-worker pumped extra syrup into two snowballs as a pair of eager young girls counted four quarters each. It was 5 p.m., peak time for the Safe Zone. Inside, each room was filled with middle schoolers and early high schoolers plotting amongst each other: art projects, romances, sleepovers, Snapchats. Shouting and chiding, they ran in and out through the small entranceway, past a white sign with thick black letters: STOP KILLING EACH OTHER.

Alston-Buck directs marketing and business development for the Penn North Recovery Center, a local social services nonprofit. At the height of Baltimore’s chaotic summer of 2015, “when everyone was watching us on TV,” she saw the desperate need for places where young people could socialize unthreatened. She opened the Kids Safe Zone in a vacant laundromat in early June. The first night, nearly a hundred kids showed up. A few high-profile grants and endorsements from celebrities like Alicia Keys allowed Alston-Buck to move her operation to a 5,000-foot space in the main Recovery Center building on North Carey Street. As the two girls dug into their snowballs, Alston-Buck was seated by the center’s exterior wall, in front of a winding collage of oversize black-and-white photos.

Those are Devin Allen’s pictures, which he installed himself in November, shortly after the new location opened. Allen has taught Wednesday night photography classes at the Safe Zone since the laundromat days. Alston-Buck is frank: Her program’s success and visibility has attracted plenty of hangers-on and do-nothing schemers. But despite his relative fame, Allen is different. “Anybody and everybody wants to use our name to get funding,” she said. “But Devin’s the only one who’s been able to create a program.”

A minute before 5:30, after Alston-Buck went inside, a red Scion pulled into the parking lot and one of girls ran over, yelling, “My man Devin here!” He emerged almost cautiously, scanning the busy scene in an Under Armour T-shirt. His cornrows were hidden underneath a green baseball hat embroidered with a portrait of Tupac Shakur, who attended Baltimore School for the Arts as a teenager. An unkempt beard jutted out from his chin.

Allen gave the girls handshakes and kidded them in a quiet voice. Then he opened his trunk and slid out a large cardboard box, lurching it into his arms with his knee. He followed the girls inside and into Alston-Buck’s office.

Allen opened his cardboard box on a conference table as a few kids gathered around. He pulled out bundles of Bubble Wrap and unwrapped them: about 20 cameras. He inspected each one carefully, peering through viewfinder, thumbing the mode switch. Then he passed them to the kids.

The box had come from San Francisco, the latest success of Allen’s social media campaign for donations. When he suddenly found himself in the spotlight, he put the word out across all his channels: old, new, digital, film — he takes whatever people have to offer. Then he brings them to places like the Kids Safe Zone.

“All cameras are good cameras,” Allen said, watching a boy scowl skeptically at a dinged-up heap with a long lens. “The film goes right there,” he said to another, who seemed mystified by the machine’s bulk and hinges.

Only three of the assembled kids were actually in the Wednesday night class — two boys and a girl. A year earlier, the class had started with ten kids, then went down to five. A few months earlier, this group had their work exhibited in a show at another community center, the Impact Hub, and even sold prints. His goal is to teach students three things: to take a picture, to properly price their work, and to keep the money.

With a handful of cameras in tow — a mix of point-and-shoots, a long-lensed DSLR, and a few iPhones — they went back out to the parking lot and embarked on the evening’s work. It wasn’t only children by the playground. A few adults had gathered on the sidewalk in lawn chairs, others had pulled vans up to the curb and sat talking in the open door. The kids wandered through the crowd, tentatively peering through their machines in search of an image that seemed honest and new.

“Y’all take a picture of me!” shouted one older woman from a lawn chair. She was denim-clad from head to toe, and held up a peace sign as the kids sprang into action. They were maneuvering into position, trying to frame her correctly in front of the chain-link fence, when they heard a telltale rumble.

“Here it comes,” one of the boys said, without needing to specify. A police cruiser zoomed down the street, and they all spun around like nature photographers at the sound of exotic birdsong.

“I caught it!” another boy celebrated as the cruiser turned a corner. The others and Allen gathered around as he showed off the sharp image on his display. Then they moved on, up the road, moseying slow.

Allen was snapping away as much as anyone, using a little point-and-shoot and looking in every direction. He took a few pictures of the top of a line of townhomes against the sky, and then a few more of a family sitting on a marble stoop across the street. He got an angle on a boarded-up house and held steady, gazing through his viewfinder.

“I shoot in manual so I can control everything,” he explained. All his advice was like this — simple observations about the technical basics. Just enough to make the students realize there were ways to bend the world to their vision.

“That’s how I shoot, too,” said the smaller boy. Allen laughed.

“You don’t even have a camera,” he teased, and the boy deflated as the other kids laughed at his iPhone, which he’d borrowed from Allen. They spotted a cat lying in a grassy patch next to one of the tall brick houses. The kids all lined up quietly.

“Don’t shoot downward,” Allen explained. “It distorts the image.” The cat ran off as the smaller boy leaned against a fence and the kids compared shots.

“Mine’s better!” shouted the girl.

“Mine’s better ‘cause it’s level,” the bigger boy bragged.

“Shut up!” the girl shot back. On they went, stopping at a corner church to decide the route’s direction. To the northeast, a hair salon and sub shop. To the southwest, more houses, more sun and boarded windows. The air smelled like weed and grilled meat, though there wasn’t any smoke nearby. The shadow lines on the pavement were growing more intense, almost like dusk in the desert. Allen took a few shots of the girl, who was adjusting her aperture to get a decent picture of the sun blasting through the clouds. They turned southwest without much discussion. Looking for what exactly?

“Life,” said Allen. “Just life.” He paused. The sun was getting longer and the houses’ sandstone facades were taking on a deeper yellow hue.

“The dopeness of living in the hood.”

Striking as it is, the Time cover shot is an outlier in Allen’s work. He rarely captures that much tumult and motion. Even in the other pictures that emerged from that day, he found the quiet moments: two protesters lost in thought, a watery-eyed black cop scanning the streets. Politics don’t interest him; dopeness does. The point is to get a face, an unguarded glance or breath, a little stillness and humanity even when his subjects are posed. He said his goal is to capture “the moment before and the moment after the picture you’re trying to get. I want the vulnerability.”

This appreciation for quiet is a relatively new development in his life. From his teens into his early twenties, he couldn’t stay inside. Every day and night he was “rippin’ and ridin’.” He ran drugs through his neighborhood and up into Baltimore County, mostly weed and codeine. His closest friends at that point were named Derrick and Chris, two guys from the neighborhood with similarly limitless energy. They nicknamed him “Moody” because he was. Allen’s right hand is permanently swollen from a punch he landed in 2008.

“I was good at selling drugs,” he said during the late-afternoon walk. He made a lot of money with his friends, but his memories of that time are full of shame and trauma. “I’ve seen people been killed, take their last breath. I share my past with them,” gesturing to his students, “because it shows you’re never in too deep.”

When his daughter was born in 2009, he took a job as workflow coordinator for an insurance company. He didn’t miss the violence or the anxiety of drug hustling, but the straight life didn’t suit him. He grew bored and depressed. Then in 2011 another friend told him to come to a poetry night. Allen was skeptical: What relevance did poetry have to his life in Baltimore? But then he went and saw there were girls there, so he came back the next week. The organizers were looking to build a brand, and Allen had some experience as a party promoter. He developed a plan.

“I borrowed a Nikon Coolpix that my homeboy had," he said. "We took pictures of the girls making heart-hands and put them on T-shirts to sell.” It didn’t have the same profit margin as codeine sales in the suburbs, but the new lifestyle had other perks: deep conversation about politics and art, and positive feedback about the pictures he took. “It was a totally different world."

This was 2012. Allen didn’t know anyone who could teach him photography, so he scoured Google and YouTube and learned the basics of composition, camera types, brand names, and even a little history of the medium. He fell in love with Gordon Parks, particularly his 1966 portrait of Muhammad Ali that highlights the champ’s eyes and gleaming sweat. Allen hadn’t yet found his own style, though this photo helped lead the way. He only knew that when he was stressed, “photography made it go away. It felt like I wasn’t there. It was my adrenaline.”

January 2013 was the turning point. Allen deleted all the frivolous “hangout photos” from his social media accounts and showed only his best, most artistic work. Then he took his grandmother’s credit card to Best Buy and got a Canon 60D. He didn’t know how to use it, but it had that chunky battery-pack grip on the right side and he knew that he “had to have that box to look official.” His old friends were still dealing drugs, but his little girl was about to turn 4. It was time to get serious, start a new chapter. He told everyone the same thing he told himself, with desperate purpose: “I’m a photographer now.”

His new poetry friends had an art space in a dingy townhouse in the arts district along North Avenue. He took girls up there to model. He labored over colors, poses, expressions. He sought out their vulnerability and honored it, heightened it. “I don’t like a lot of makeup," he said. "I don’t like doing too much to the picture after I take it.” He showed the girls thinking, breathing, standing outside among trees and dappled sunlight.

A phrase kept popping up in his mind: a beautiful ghetto. The way light shines off a new car rolling past busted windows. The complex, loving social rituals of people without jobs or air-conditioning. The look of pride on a person’s face when someone with artistic sense deems them worthy of a portrait with a nice camera. The soft moments that never make it to the newspaper, the ones only locals see. He finally had his subject.

Allen was editing photos at the house when he got the call he’d been dreading: Derrick had been murdered. Shot seven times by rival dealers. It was a Friday night. He went quickly to his see friend Chris at his mother's house. “I told him, ‘Don’t do anything crazy, drop your gun off, go see family for a little while.’ Saturday night, they got Chris, too.” The same rivals. To Allen, the message was clear: “Photography saved my life.”

So he gave even more to it, and even more to the city that obviously needed positive-minded people. By the summer of 2015, he had a night-shift job helping residents with disabilities at an assisted living facility about 30 miles south of the city, and he devoted the rest of his time to art and activism. From midnight til 8 a.m., he changed adult diapers, followed by a day of photography and editing and a night on the streets with whatever protest, poetry reading, or social cause was in need of warriors. Every day like this, except for the two weekends a months he had custody of his daughter. And then the Baltimore police killed Freddie Gray.

The best documentary photos are so evocative and affecting that single frames come to embody entire issues, cities, eras. Fifty years on, when we think of a nonviolent protest in the South, we envision a somber Alabaman walking into a dog attack. When we think of the Dust Bowl we think of “Migrant Mother.” The Vietnam War is synonymous with “General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner in Saigon,” while East African famine is embodied by “The Vulture and the Little Girl.”

These photographs, among the most famous of the 20th century, were produced by major artists working for major institutions: the Works Progress Administration, the Associated Press, the New York Times. (In most cases they were recognized by another massive organization, the Pulitzer Foundation.) For many years there was simply no other way to support such talent in such faraway places, often for long periods, let alone to print and distribute them for a mass audience.

That’s still the case when it comes to most high-profile photojournalism in major magazines and newspapers, and as Reuters’ Jonathan Bachman recently showed in Baton Rouge and Charlotte Magazine’s Adam Rhew showed in that city, there is still an appetite for artful photojournalism that distills an entire conflict down to one poignant image. But the cultural role of documentary work is evolving, and the artistic measure of it is adjusting to the new paradigm as well.

“Most other photographers are still newspaper staffers, though the rules are changing,” said Indira Williams Babic, director of photography and visual resources at the Newseum in Washington, DC. “There are eyes everywhere now, and sometimes, like Devin, they live in the areas or are part of the communities. And they can disseminate it immediately, without censorship.”

The foremost documentary images of this civil rights era are first-person dispatches, not detached journalistic observations: Think of Walter Scott’s assassination shot through a park fence by a stranger, or Eric Garner’s death captured in portrait mode by his nearby friend who is now in prison. The whole point of these videos is that they provide a view that no news camera could capture, though like Devin Allen's work, they are occasionally brought to cultural prominence by the gatekeeper media that now relies on them for content.

In the same way that anyone can now perform a journalistic service, the democratic veneer of social media has bled over into the fine-art world as well. This has occasioned multiple recent controversies: the Tate Modern’s solo exhibition by social media–based artist Amalia Ulman, for example, or conceptual artist Richard Prince’s ethically dubious sale of other people’s images for hundreds of thousands of dollars. The definitions of “real” art and “real” documentary work are getting simultaneously blurrier and more rigid, but Allen’s self-taught, thoughtful approach satisfies them both. His technique qualifies him as an artist, while his revelatory view of inner-city life qualifies as reportage.

Social media has attracted other street photographers who embrace its capacity for hyperpersonalized, intimate work. In between photojournalism work, Jamaican-born Ruddy Roye roamed New York for years, shooting the downtrodden and dubbing himself an “Instagram humanist/activist.”

Then the New Yorker invited him to take over its Instagram feed as he shot Hurricane Sandy’s aftermath on his iPhone. After years of freelance hustle, he suddenly became an in-demand magazine contributor. Chris Arnade, the Wall Street banker turned portraitist, sought out Bronx drug addicts and posted his photographs to Tumblr and Flickr before eventually having them published in The Guardian. He has spent most of 2016 photographing the rural poor for that website, while also posting his photos and political analysis on Twitter and Medium. Roye and Arnade are prolific and unafraid to caption their work, sometimes voluminously, to convey its social and political import. Their work is personal — even too personal for people who prefer more detachment in their photojournalism. But they show how social media has changed the medium, heightening the expectation of intimacy and communication between artist and audience as well as artist and subject.

“The days of the white guy parachuting in are over,” said veteran Baltimore photojournalist J.M. Giordano. “Devin shoots as an insider. He has trust. He has more sympathy and empathy for his subjects. Anyone can take a photo of a kid running down the street, but when you look through that viewfinder and grasp the light and the composition, that’s something different. He marries those worlds.”

But the spotlight brings its own pressures and expectations. The Time cover turned Devin Allen into a photojournalist, community spokesman, and social media figurehead, but he was also an activist, a father, and a heavyhearted young man — and all these competing roles made his next few months particularly exhausting.

Throughout the hot, powder keg summer of 2015, Allen appeared on neighborhood social justice panels and came to talk with every classroom in Baltimore he was invited to; he even donated his photos for an exhibit at the downtown Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African-American History & Culture. He solicited the camera donations through social media. He met with seemingly every outside photographer who arrived in Baltimore looking to take pictures of the latest trendy American ruin.

“People come in and want to take pictures, but they don’t do it because they care,” he said on his Wednesday afternoon walk through the neighborhood. “Why don’t you talk about Freddie Gray’s living conditions? The school cuts? We live here every day.”

He was watching from a distance as his students photographed a group of shattered windows on a gutted brick row home. “Why do you stop and take that picture?” he shouted to them.

In unison, expertly rehearsed, they shouted back: “'Cause it’s a beautiful ghetto!”

Even after Time, he was still working full-time at the assisted living center, commuting a half-hour or more each way. He was flirting with a nervous breakdown all summer long, the city’s ongoing drama compounding his own high standards for himself. Coming home after work one early morning, he fell asleep at the wheel and ran off the road. Somehow he avoided injury, but his car was totaled. It was another wake-up call. He’d survived a drug dealer’s life only to nearly die of exhaustion. He needed a change. He needed balance.

Allen was offered a few photojournalism jobs at newspapers, but he was concerned that if he took such a post, “I’d be sent to every Black Lives Matter thing. I don’t want to be paid to document my people. This is my purpose as an artist. I don’t want to go to other places. I need to do as much work in Baltimore as I can.”

That’s when Under Armour, of all places, reached out. "It’s damn near impossible to go from the street to work at a billion-dollar company," Allen said. "I’m here to make a point. There are amazing artists from the inner city who deserve a chance to work here." Allen foresaw a situation where he’d learn his craft from trained professionals, meet famous athletes and get free gear, and essentially receive corporate patronage for his community work. Perhaps most importantly, he’d live a daily 9-to-5 life far away from the various debates and dramas that loom over every aspect of his life. For eight hours a day he could take pictures without worrying about artistic legitimacy, community struggle, minority representation, politics, social media trolls. For the first time in his life, he had the privilege to live a portion of every week in relative silence.

As he returned to the Safe Zone, Allen’s three students sat on the wall by the parking lot, uploading their best pictures to Instagram while mocking each other’s usernames for their corniness. Suddenly a group of young teenagers ran over from the playground, heading for the empty lot behind the building.

“They fightin’!” one girl yelled. The photographers shook their heads and stayed focused on the iPhone.

Allen was thinking about the uprising anniversary and the fact that he’d largely avoided marches in 2016, especially the widely covered Unity March pegged around the first anniversary of the uprising. That’s increasingly his way. “Protesting brings media attention,” he said, “but what do you do when you have that attention? You protest to get to the table. I got into the Smithsonian, and now I don’t protest so much. I’m needed elsewhere.”

It’s a precarious balance: close enough to the street to take the photos that previous generations couldn’t, but deep enough into the professional world to make sure that those photos have the greatest impact. He made sure that the work he gave the Smithsonian weren't just from protests. "There's a picture of my mom dancing," he said. "I have a selfie in the museum. And it's important for me to be in these spaces because I want to control the narrative around my photographs. I don't want to see them on a T-shirt." He had just returned from Venice, where he exhibited pictures and spoke at an event during the Biennale. Earlier in the summer, he signed a deal to release a photo book in 2017, tentatively titled — what else? — A Beautiful Ghetto. It will include photos by the young people he spends his Wednesday nights with.

But Baltimore has a way of drowning out personal celebrations. The city’s murder rate for 2016 isn’t quite as high as last year’s near-record violence, but the city is still on pace for nearly 300 killings before January. The public schools haven’t allowed students to drink tap water for nearly a decade due to elevated lead levels. In June, State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby dropped all charges against the six officers involved in Freddie Gray’s death, after the first three trials failed to produce a single conviction. Activists and the city council have extracted certain concessions from Under Armour, primarily a promise that 20% of the housing built in its new mini-city will go to low-income residents, but plenty of people, including many who Devin Allen knows and respects, are sick over the corporate charity being offered at all.

Allen doesn’t take all this lightly; he doesn’t take anything lightly. His his mind still stirs and churns. His accomplishments are dulled by a sense of responsibility toward his struggling hometown. His newfound stability is tempered by loved ones’ lives lost to prison and gunfire. In his telling, “I have a job, I make money, but I’m not content.”

Then, of course, there’s the election that just revealed the lie beneath any optimistic accounting of the country’s racial progress. The morning after Trump’s victory, Devin Allen was surprisingly sanguine. He’d been approached to support or endorse a number of candidates, from the Baltimore mayor’s race to the presidential campaign. He declined all requests, and sees his mission as one that transcends politics, let alone one race.

“This just proves the point that what I'm doing is important. I'm just going to work harder,” he said by phone. “The anger you have, the sadness you have, turn that into inspiration. Every day, you need to be doing something. If you want equality and the things you were voting for, don't go hiding in the house. This is war, it's not stopping. If Hillary had gotten in, I would have told you the same thing. The system isn't set up for us, black people and immigrants. But there are so many ways to make change beyond voting.”

At the Safe Zone, Allen looked over at his students, who were discussing plans to get home while the last of the playground stragglers trickled through parking lot. One boy, the smaller one, needed a ride back to the city’s east side, so Allen requested an Uber. Astounded, a group of kids gathered around his phone and watched the cartoon car swerve through the neighborhood map. The young man looked terrified to ride with a stranger.

“It’s safe,” Allen assured him, loud enough that everyone could hear. “I took Uber in China.”

“You’ve been to China?” one girl asked. He had, to photograph Stephen Curry for Under Armour the previous winter. The black car pulled up to the Safe Zone and the boy fist-pounded Allen with thanks for the evening, then walked sheepishly toward his ride while all the girls teased him without mercy.

After a year-plus on various front lines, Allen’s focus has narrowed. He has his daughter, his job, and his teaching, all of which he documents thoroughly and publicly. In September, Allen gave his personal camera away to a student whose ambitions were outgrowing his budget. The daily obstacles have not ceased, but he’s not trying to save Baltimore anymore; he’s trying to make the biggest difference he can with a camera and a platform.

“I need to be here,” he said, watching the young man climb into the Uber. “They need to see me stepping out of my grandma’s house, in the club, at the Safe Zone. I have to prove that you can come from a place like this and be larger than life.” •