Two-thirds of humanitarian workers have experienced or witnessed some form of sexual violence on the job — but nearly half of them have never reported it, according to a new survey.

Fully 85% of humanitarian workers said in the survey that they had either experienced sexual violence themselves, witnessed it, or have a colleague who had experienced it.

The Report the Abuse survey is the first of its kind: Internet-based, self-reported, and available in 30 languages. The data from the survey are not a complete picture of the problem — but in an industry where virtually no statistical information on the problem otherwise exists, the survey is a major step forward.

"We don't really have any concept of what sexual violence is being experienced by humanitarian workers," said Megan Nobert, founder and director of Report the Abuse, which released a report on Friday.

Nobert, a gender-based violence expert and human rights lawyer, founded the organization in 2015 — BuzzFeed News spoke to Nobert last year about her experience trying to get justice after being sexually assaulted by a United Nations contract worker in South Sudan.

A USAID-supported Aid Worker Security Database records only 26 incidents of sexual assault against aid workers, globally, since 2004. But that database is limited to cases of rape or "serious sexual assault," which leaves out a great deal of behavior experts consider sexual violence, including harassment or unwanted sexual comments, unwanted touching, sexual abuse, and sexual exploitation. In other surveys of aid worker safety, it's difficult to find any mention of sexual violence at all.

"When statistics suggest it's a one off thing every couple of years, it's easy to dismiss the issue," Nobert said. "Having numbers does start to show that this is more of a problem beyond one or two people saying this has happened to them. Acknowledging there's a problem changes the landscape on how we discuss the issue."

A quarter of the humanitarians who responded to Nobert's survey said they had had more than one experience of sexual violence on the job. More than 55% of respondents said the perpetrator was a colleague. Forty percent reported that the perpetrator was an expatriate staffer; 25% said the perpetrator was a local community member; and 17% said the perpetrator was a local humanitarian worker.

Nearly 40% of those who experienced sexual violence on the job reported it to their organizations, but only 17% felt the complaint was handled appropriately.

That's one reason, Nobert said, that there's so little understanding of the scale of the problem. Retaliation is a common fear — and, in many cases, a reality — for survivors, she said.

But poorly handled reports can also add to the trauma of the survivor, making it that much harder to cope with and heal from the experience.

"The first person you talk to will have an impact that the entire process will have on your healing, and if that first person... dismisses you or reacts in a manner that suggests you deserved it or you’re lying or one of the myriad awful reactions you can imagine, that will send you down a garden path of trauma," Nobert said. "I know that from personal experience."

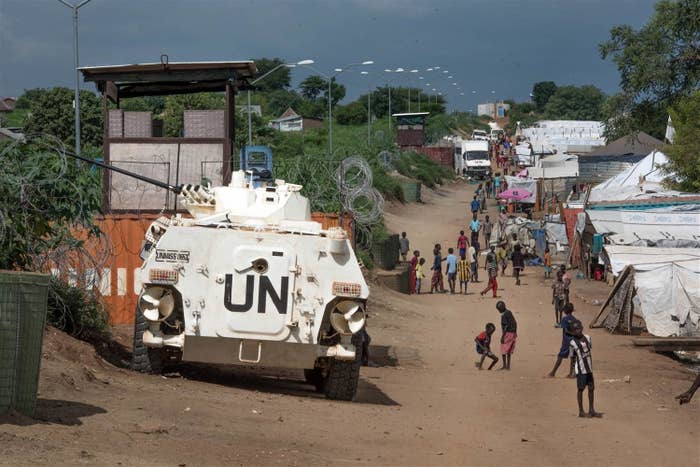

Nobert's report comes on the heels of news out of South Sudan this week that humanitarian workers were beaten and multiple women were raped by South Sudan forces at an expatriate compound during fighting last month in Juba. The United Nations chose not to respond to the incident, despite repeated emergency calls, according to documents obtained by the Associated Press. Meanwhile, aid workers started a petition to better the security standards where they work.

The report also surveyed international humanitarian organizations about their sexual violence policies. Nearly 10% of the organizations in the survey had no policy at all.

Several of the major players — including the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the European Commission's Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection — use victim-blaming language in their security policies, according to the report.