When Mark Zuckerberg announced that he would change Facebook's News Feed algorithm to prioritise content produced by friends over posts by pages, it caused consternation in news organisations around the world as publishers tried to figure out the impact it would have on their readership.

But they were not the only ones to feel anxious about the social media giant's move. Britain's political parties, which over the last few general elections have increasingly used the world's largest social media network to target voters and spread their message, fear that the algorithm change could turn their online campaigning operations upside down.

Tory and Labour digital strategists have told BuzzFeed News that their ability to reach millions of ordinary voters could be under threat as a result of Zuckerberg’s tweak. Senior staff at both leading parties have raised concerns, with meetings arranged to discuss the issue.

Craig Elder helped pioneer the large-scale use of paid-for targeted political Facebook advertising in the UK for the Tories in the 2015 general election, the first time in more than 20 years the party won a clear majority.

He told BuzzFeed News that if Zuckerberg makes good on his promise to reduce the amount of professional content in the News Feed – meaning people are more likely to see a relative’s holiday pictures than posts by a politician or news outlet – it could force parties to adopt a strategy that requires them to spend millions of pounds buying targeted Facebook adverts.

"If where we end up is that people with loads of money are the ones who'll get their particular views heard and everything else gets crushed, then we're pretty much back where we started," Elder said.

In last year’s snap election, Labour’s Facebook strategy relied on reaching people for free with official content, something which benefited the party enormously.

But many of the online campaigning tactics that worked so well for Jeremy Corbyn's party during the 2017 election could be – if not broken – less effective than they were six months ago.

Elder speculated: "Tories in 2015 would still work, Labour in 2017 probably not as much."

This fear of Facebook forcing politicians to pay to spread their message is widespread among political digital strategists BuzzFeed News spoke to.

"If you took an extreme case then Facebook could decide that it’s just about people’s friends, and adverts," said an individual at the pro-Corbyn campaign group Momentum. "There’s no guarantee they won't do that."

As another political strategist put it: "It may just be that Facebook's way around all this is just 'pay us cash'."

The Conservatives are already desperately trying to catch up with Labour in the world of online campaigning: New party chairman Brandon Lewis has promised to arm activists with "graphics, GIFs, and videos", while the party's Instagram account no longer posts stern pictures of Michael Fallon.

However, the algorithm change raises the possibility that the Tories could be building a campaign team suitable to fight the last election but not the next one.

"People are going to have to look at how to push information out," said Beth Wheatley, a former Tory digital director. "People got lazy. There’s going to have to be a back-to-basics reexamining of the sort of content people were using."

The accepted narrative in Westminster around the 2017 general election is that Labour managed to outwit a technophobic Conservative party and circumvent a hostile national press thanks to clever viral videos that pushed a clear message tailored to social media, supported by a new set of left-wing media outlets that dominated the British public's Facebook News Feeds, and tactical advertising buys on services such as Snapchat.

Accepting this version of events allows you to conclude that Labour’s online operations could have had a crucial impact in the 19 constituencies Labour won with majorities of fewer than a thousand votes, which in turn was enough to deprive Theresa May of a majority in the House of Commons.

Facebook did not to respond to specific requests from BuzzFeed News for comment on how the updated algorithm will affect content produced by British politicians and parties, while a lack of reliable statistics means that measuring the impact of social media campaigning still relies heavily on guesswork and speculation.

One individual who had a meeting with the company about the changes suggested that even Facebook's own UK staff weren't exactly sure how it would impact the ability to distribute political material.

But the extent to which changes to the algorithm, a piece of code that effectively controls what tens of millions of Britons see when they open Facebook, concern political campaigners is extraordinary.

"Political parties might find their advertising suddenly becomes much more expensive," said Wheatley, the former Conservative staffer. "The reason people adopted [Facebook advertising] is that it was much cheaper. The cost per interaction was incredibly low. If all of a sudden it becomes almost as expensive as knocking on a door or sending something through the mail, then there’s going to be a look at which things are actually delivering."

One effect of the algorithm changes could be a return to smaller filter bubbles, where supporters of a particular party continue to see large amounts of political material that supports their worldview but it becomes less likely to seep out into the world of undecided voters and people who care little for politics on a day-to-day basis.

"My sense is that the core vanguard will stay as informed as it is before – the Labour supporter with lots of Labour supporters in their feed who still subscribes to lots of Jeremy Corbyn pages," said Alex Krasodomski-Jones, a researcher at the Demos Centre for the Analysis of Social Media, suggesting the changes could result in these tighter, smaller bubbles.

"The question is what happens to the floating voter, the disinterested political middle, who doesn’t have that same community and is more reliant on traditional sources of news to make decisions about their politics."

Labour is aware of the risk that the Facebook changes could potentially damage its ability to reach floating voters. One idea circulated within the party is to have a WhatsApp group of leading activists who agree to share posts on their own Facebook profiles, in order to get content out there and circumvent any News Feed changes.

"There could become a question where the seeding doesn’t happen through one post by the Labour party, it happens by encouraging lots of independent posts to be created," said a campaigner.

Another Labour campaigner said they hoped that their ability to reach voters can be saved by Facebook's decision to prioritise content that prompts lengthy discussion, saying: "Jeremy has huge numbers of comments on his stuff."

A lot depends on to what extent Facebook follows through on its plan to downgrade the visibility of professional content in favour of content from friends.

Elder, the former Conservative online campaigner, urged caution: "How much of this is real and how much of it is Zuckerberg feeling that he needs to get belatedly back in the game and tell a story about Facebook that isn't 'It's terrible for your mental health, it's destroyed politics, it's destroyed news, it just sells all your data to bad people who want to sell you things'?"

Krasodomski-Jones speculated that the biggest damage could be to new pro-Corbyn viral news websites such as the Canary and Evolve Politics, which use "sensational, viral-style news" and rely almost entirely on Facebook for distribution. It was these outlets which helped push anti-Tory stories around fox-hunting and the ivory ban into the mainstream.

Matt Turner, the deputy editor of Evolve Politics, insisted his site had yet to see a "tangible" change in traffic and hoped to bypass most of the Facebook changes due to its articles going viral in pro-Corbyn Facebook groups at first and then via individuals.

"Time will tell, though," he added.

The algorithm change is already forcing political campaigners, like news publishers, to look elsewhere at other social networks, potentially ending an era where Facebook was the only way to get a truly mass online audience for political material.

Traditional news websites could become more important again, as could convincing people to visit official websites and download party-branded apps – one post on culture secretary Matt Hancock's inadvertently popular personal social networking app this week received more interactions than some of the posts on the official Tory party Facebook page.

Another option is for national parties to produce templates for local content, which can then be pushed out on a constituency level. Momentum, vaunted for its viral videos, is banking on its content being entertaining and engaging enough that it still goes viral on Facebook – even if it's on a smaller scale than before.

There's also the question of whether Facebook delivers the voters that parties need, with younger voters more likely to be using services such as Snapchat.

One Labour source said the party found it easier to reach voters aged 55 and over with Facebook adverts during the last general election than people aged 18 to 24, since the latter group were less likely to be active on the network.

What's clear is that the enormous reach of politicians' own official Facebook pages which, along with millions of posts by individuals, helped upend politics during last year's general election, has not extended beyond the campaign.

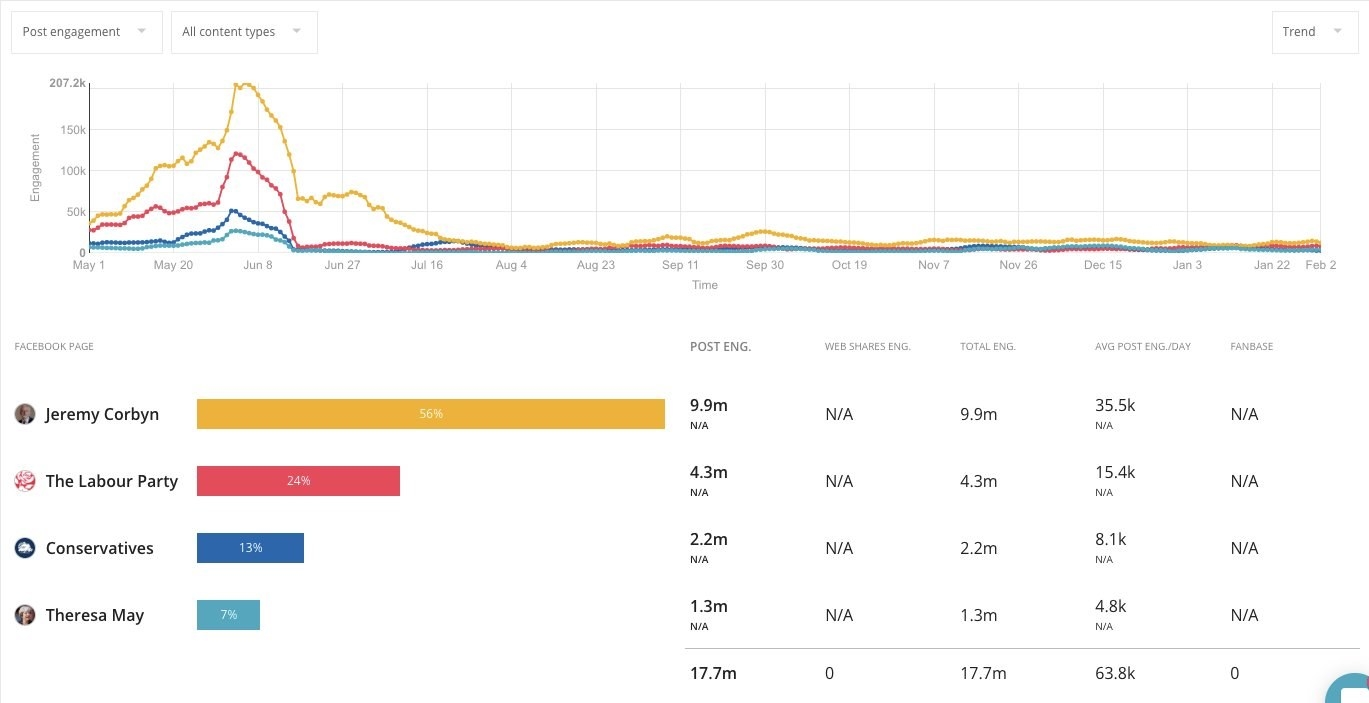

Data analysis provided to BuzzFeed News by Steve El-Sharawy of EzyInsights shows the enormous drop-off in interest in Facebook material produced by Corbyn, Labour, the Conservatives, and May following the general election.

While the social network turbocharged engagement during the contest, people are less minded to interact without a major national political event. El-Sharawy is also yet to pick up any major shift in how people interact with politicians following Facebook's announced changes: "Either there has not been any change put into action yet, or it's, well, not doing much."

This is combined with concerns about the overall drop in time users are spending on Facebook. "The real interesting story is the stuff that came out on the amount of people using the platform," said a Labour campaigner. "A combination of this [algorithm] change and less people using it means less people are going to get their stuff seen."

Meanwhile, new data protection regulations are set to make it even harder for political parties to harvest data. Parties have traditionally built up enormous mailing lists by encouraging people to sign petitions or take part in viral apps, such as when Labour asked people to calculate their NHS baby number. In the process they have harvested hundreds of thousands of email addresses from people who were not necessarily always noticing the small print that said they would be consenting to be bombarded with campaign material.

New rules, due to come into force in the coming months, will now require people to actively opt in to the mailing lists – with the onus on the political parties to prove that this took place. The end effect is likely to be a substantial drop-off in the number of people willing to hand over their contact details to politicians.

Despite all this, some things about social media have remained the same.

El-Sharawy said his analysis of interactions with political material posted by British politicians showed that, despite the changes, there are still certain pieces of content that are guaranteed to do well.

He said: "The only time Theresa May was more popular than Corbyn recently was when she posted a picture of a dog."