Labour quietly spent £1.2 million running online adverts in the run-up to the general election, campaign sources told BuzzFeed News, using in-house software to microtarget individual voters on Facebook while also unleashing a Snapchat advertising blitz that was seen by 8 million people in one day.

Before the election the media focused on the Conservatives’ supposed “dark ads” Facebook campaign in target seats, which was often portrayed as being underhand due to its reliance on difficult-to-track unpublished adverts.

In reality, according to Labour campaign sources, Jeremy Corbyn’s party was quietly running a potentially more sophisticated under-the-radar in-house targeting operation that relied heavily on many similar targeting tactics, culminating in a £500,000 online ad blitz in the final two days before the vote.

Conservative campaign sources separately told BuzzFeed News that they expect the total bill for their digital campaign to be in the region of £2 million across all platforms.

This suggests the total online advertising spend for all parties during this election is at least £3.2 million and could rise substantially when the Liberal Democrats, the SNP, the Greens, and other parties are taken into account – underlining the extent to which spending enormous sums of money advertising on Facebook, Google, and other services is now considered to be a key part of all British political campaigns. Official figures will not be confirmed for several months.

The reach of the online advertising campaign was such that potential Labour voters in marginal constituencies who verbally raised concerns about the NHS to a party activist on the doorstep would find their Facebook feed targeted with adverts warning about the state of the health service the following day.

"Someone would knock on your door, we’d find out you’re Labour, and that info would get entered back into our voter databases," said one campaign source. "Overnight we’d match you into a new voter pool on Facebook, and you’d start getting adverts within 24 hours."

At the heart of the Labour digital strategy was a system that allowed the party to build in-depth profiles of individual voters, work out whether they voted regularly, personalise the campaign material these individuals received in the post and online, and hammer home relevant messages.

Voters who were asked for their political opinion in key marginal seats had their responses fed into the party’s central voter database. Labour's digital team then deployed proprietary software called Promote to link individual voters to their Facebook profile, helped by cross-referencing email and mobile phone details. The system would then look up which issues the voters told Labour canvassers they cared about and begin targeting them with relevant paid-for material.

The system was tested during Sadiq Khan's London mayoral campaign, but this was the first time it had been deployed on a large scale. The in-house Labour tool includes a public dataset of who has voted in previous elections, enabling the party to send different messages to different groups, depending on how likely they are to turn out – such as paying to target ads at people who only bother to vote intermittently in general elections, saving the party from spending money on regular voters or habitual non-voters.

If a voter was due to receive election material through the post on a particular issue then Labour’s digital team would try to ensure they also saw Facebook adverts relating to the same topic for several days, in order to push the point home.

The level of targeting used by Labour shows the extent to which the party’s operation has changed since the 2015 general election, when Labour's digital campaign was massively outspent by the Conservatives, who were the first to pioneer large-scale political Facebook advertising in the UK and claimed the tactic helped them win dozens of closely contested seats.

This time around Labour was determined not to repeat the same mistakes and already had a team in place when the election was called.

In a sign of how much things have changed, Labour was even cross-referencing individual devices with voter data in order to ensure key swing voters were receiving the same adverts on multiple devices.

"We’d find that you as an individual were using this Mac and that phone and we were targeting those devices," said the source who worked on the 2017 campaign. "We did both of those to ensure we were targeting exactly the people we wanted, and the postcode was the fallback."

Although the party spent roughly £500,000 of its online budget on Facebook – compared with only around £20,000 on Twitter advertising – one of the biggest successes was pre-roll video adverts promoting Corbyn’s policies, which appeared on YouTube, local news sites, and on mobile phone games.

"You’re playing Angry Birds on the free version, we’ve identified you in our target audience, and you have to watch this video," said a Labour campaigner.

Headlines would be tested to see which performed better – enabling the party to quickly tell if a video about the health service would reach more people if it was headlined "The NHS is in humanitarian crisis" or "Only Labour can save the NHS".

In constituencies where Labour had a poor ground operation, the party would create models of which demographics were likely to be receptive to the Labour message and then adjust their approach accordingly.

"Our targeting analysis team will use the data ... to build models of who we think are likely Labour voters," explained one source. "We’re able to model out quite accurately who could potentially be a Labour voter. We have data other people don’t have."

Labour campaign staff suggested they had been amused by some of media coverage of the Conservatives’ negative online adverts, which may have helped distract from Labour's own efforts by portraying the Tories' messages as "dark ads".

"Anyone who was doing Facebook advertising was doing unpublished page posts or 'dark ads'," the Labour campaign source said. "It is not dark ads, it is just advertising! But it sounds more sinister."

The enormous volume of pro-Corbyn online material produced by supporters helped power the Labour surge but party officials insist it was still worth spending the enormous sum on internet advertising during the campaign.

"Organic stuff is always going to mobilise people who are engaged with what you’re doing but you can only guarantee the people who need to see your stuff are reached through paid advertising," said the campaign source.

Labour spent heavily encouraging people in target constituencies to like Labour's official Facebook page in the hope that new followers – who could cost around 11 pence each to acquire – would start sharing material of their own accord, saving the party money in the long run.

When people followed the Labour Facebook page it meant their names would appear when friends saw paid-for Labour adverts in their feed – essentially giving the impression the followers were endorsing the promoted message.

By the end of the campaign Labour was redrawing its online target list and pushing online advertising money into targeting swing voters in constituencies that would never have been considered winnable at the start of the campaign. This was aided by hundreds of thousands of pounds raised from Labour members with the explicit aim of funding Facebook adverts, solicited in emails that emphasised how the Conservatives were using similar tactics and how Labour needed money to compete.

"By the last two weeks we had extended the list into Cardiff North, Peterborough, Canterbury," the campaign source said. "At the beginning we were doing offensive seats but with display advertising on local websites and a little bit of Facebook. As we got closer to the end of the campaign we got more money and we put all of those seats into all the channels and by the end it was a large spend in a lot of offensive seats."

Crucially, Labour HQ also hopes to keep spending money on targeting voters outside of election periods – which will enable local constituency Labour parties to use the same database and software to target voters, giving local campaigners access to tools that would traditionally have been run out of the party's headquarters.

The party's campaigners are particularly proud of their decision to invest heavily in Snapchat. A party source said an "I'm voting Labour" image filter was viewed 36 million times by 7.8 million unique users. This helped to drive 1.2 million views to a Labour-built site that helped people locate their polling station.

Labour is paying for sponsored Snapchat filters today which is helpful if you want make any historical figures say… https://t.co/N4nw9PgZqu

In comparison Tory campaign sources told BuzzFeed News their adverts struggled, partly because they were wrongly targeted in places. The party wasted money advertising to voters in constituencies such as Labour MP Dennis Skinner's Bolsover seat, where, the sources said, Conservative HQ wrongly thought they had a realistic chance of winning, in part due to a reliance on data provided by the US election campaigner Jim Messina.

Unlike Labour, which benefited from being a party of opposition, Tory campaign sources also told BuzzFeed News their party had done little to develop its online operation beyond the 2015 campaign, with Theresa May having almost no substantial internet presence.

The prime minister's personal Twitter account follows nobody and tweeted only irregularly, while her team only created a Instagram account for her in the final month of the campaign. It has barely been updated since the election, and May has received limited grassroots support online.

The party also saw little enthusiastic engagement on social media, which was dominated by left-wing outlets and material.

As a result the Conservatives' digital campaign focused on relentless attack adverts and on the personalities of Corbyn and shadow home secretary Diane Abbott, reaching millions of people but rarely being shared organically.

Unlike in the last election, when Labour barely spent money on online advertising, the Tories found themselves competing in marginal constituencies with a Labour party that had learned its lessons and was willing to spend cash promoting targeted messages.

However, Labour campaigners begrudgingly admit they were impressed with how the Conservatives identified legal loopholes in electoral law to allow highly localised Facebook adverts to be paid for without breaking national spending limits.

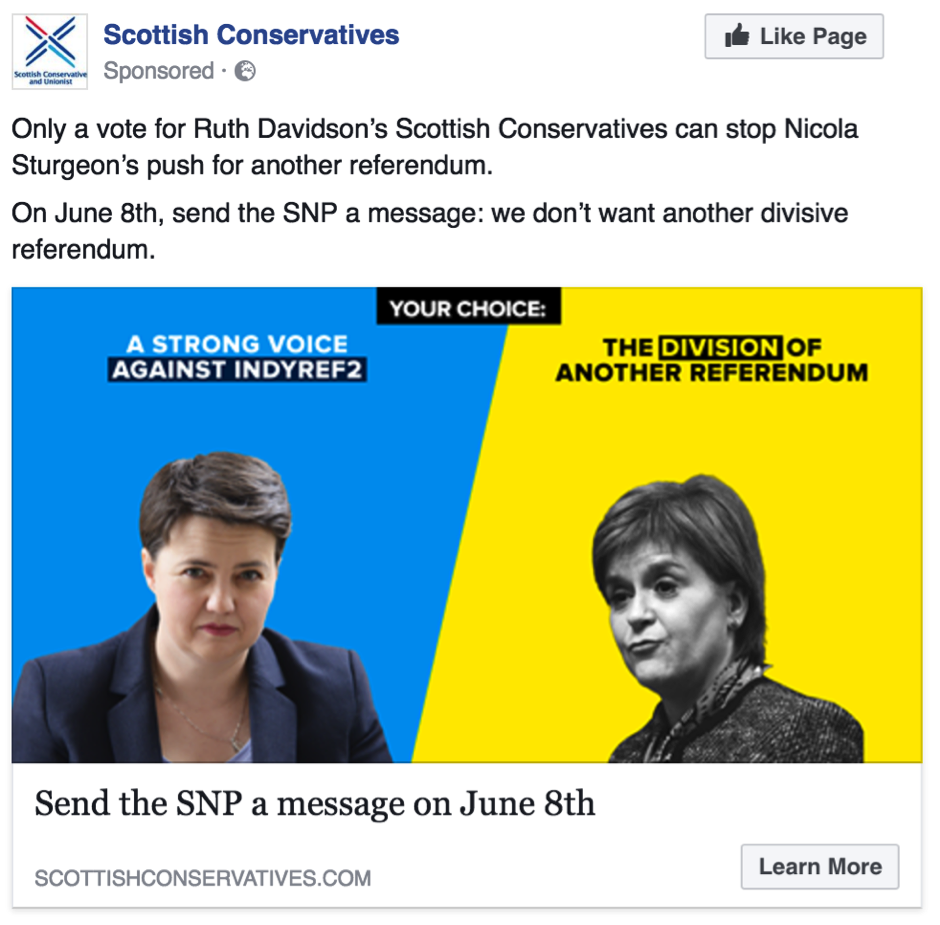

Tory adverts obtained by BuzzFeed News also show how the party increasingly put online resources into fighting two regional battles: holding off a Liberal Democrat comeback in southwest England and supporting Ruth Davidson's Scottish Conservatives in key target seats.

Voters in Yeovil – the former seat of ex-Lib Dem leader Paddy Ashdown, which unexpectedly went Tory in 2015 – were told that voting for anyone but the Tories would allow Corbyn into power. The advert, paid for out of the Tories' national funds, was an attempt to suppress the Liberal Democrat and Labour vote.

Scottish voters in SNP-held Tory target seats were bombarded with Facebook graphics emphasising that only Davidson could stop a second independence referendum, an effort that Scottish Tories credit with helping them win a dozen constituencies.

The party also increasingly shifted to defensive adverts to attempt to shore up the vote in outer London boroughs as it became clear the election campaign was faltering.

Despite some successes, things kept going wrong for the Tories' online campaigners. In one particularly egregious example, an email to Conservative activists urging them to go out and vote on polling day was supposed to be sent at 1pm, in time to be read by people heading home from work.

Due to an error many Tory supporters instead ended up receiving it at 4am the following day, at a time when results already showed party losing dozens of seats to Labour by small majorities.

Both Labour and Conservative sources talked down the extent to which they were microtargeting individuals based on personality traits, as suggested by some reporting on the likes of the data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica. The sources suggested it would be too much effort.

The Tories also strongly deny allegations they in any way reused campaign data from the EU referendum. Instead campaign sources from both camps said they used their own proprietary software and their own on-the-ground data but did not do anything more sophisticated than the many large businesses that run major online advertising campaigns.

Matthew McGregor, who ran Labour’s digital campaign in the 2015 general election, said the use of online political advertising – and the money required to support it – had changed massively since the last contest.

"In the last election Labour did great, scrappy campaigning, raising more money, mobilising more people, and reaching more voters than ever before to that point, scoring the first viral hits from a political party," he said. "But we did it with very little money and with a political platform that didn't connect strongly enough with people."

But he said it still relied on having a leader and policies that people wanted to listen to.

"In 2017 Labour fought a campaign with a leader and a platform that resonated more with people than 2015. They used smart digital tactics to make the most of that, but ultimately what makes a successful campaign is having someone, and policies, that people are passionate about."