Mike Lucero's family has been running cattle in the mountains of New Mexico for five generations, on land that the Spanish crown once deeded to settlers and has been a grazing range longer than it has been part of the United States. But in October 2014, he drove to a pasture used by his herd and found himself outside a newly-erected fence meant to protect a tiny mouse few have ever seen.

The elusive animal — the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse — is a rodent native to the American Southwest that hibernates for nine months of the year, and thrives when it can hide among tall grasses near springs and rivers.

But its diminutive size notwithstanding, the mouse has become the unlikely catalyst of a land battle — one which echoes the growing tensions across the West that have led to repeated standoffs and acts of local defiance.

The conflict stems from the federal government's listing of the mouse as an endangered species in June 2014. Five months later, Lucero and a few other ranchers showed up at a pasture they had used for grazing, only to find U.S. Forest Service staffers erecting a fence to protect the mouse's habitat.

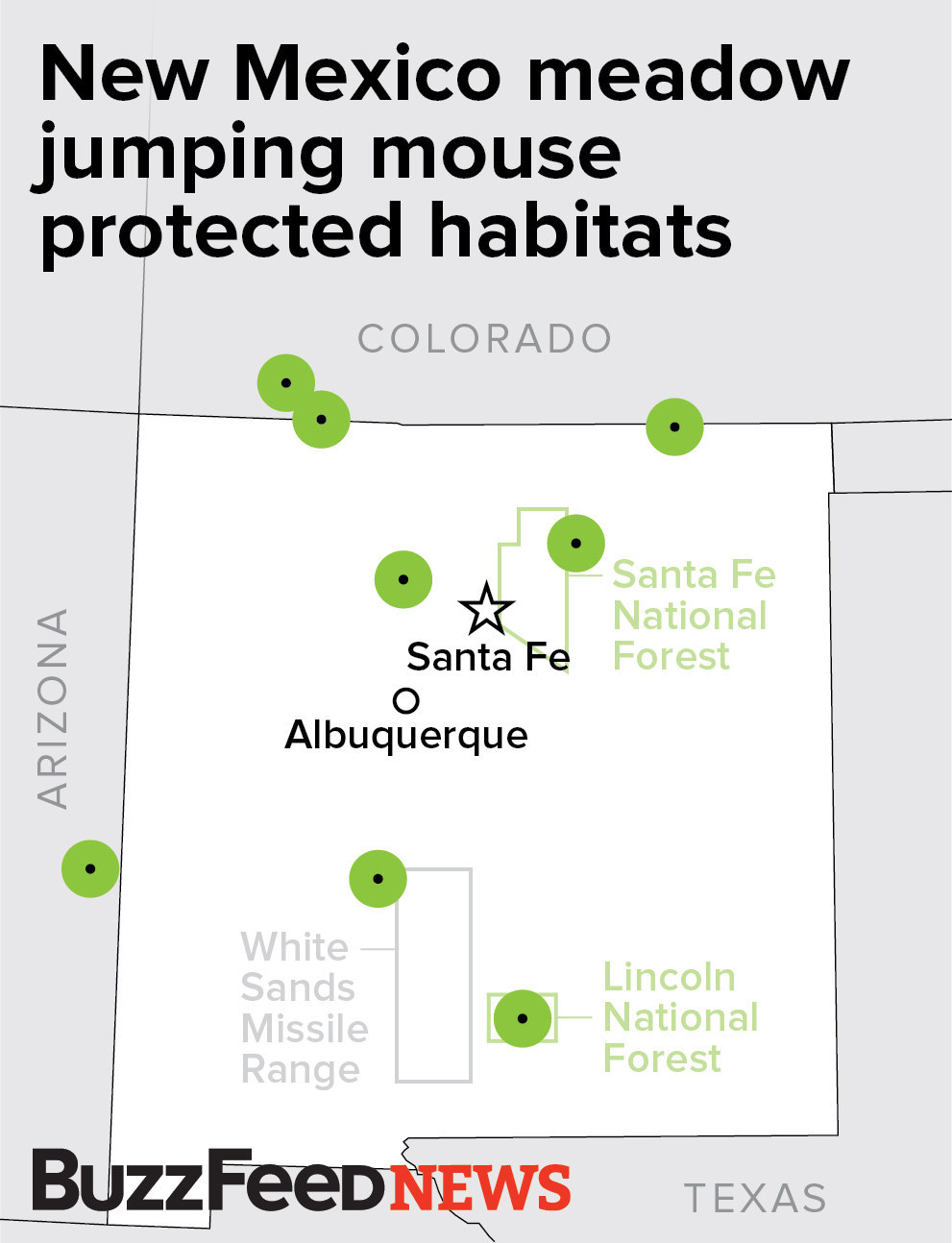

Last month, federal authorities set aside nearly 14,000 more acres of land scattered across New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado as protected habitat for the jumping mouse.

Conservationists have hailed the designations, insisting it will protect an important species on the brink. But ranchers across the region say they're the latest salvos in a long and bitter fight over their livelihood.

The conflict over public lands in New Mexico spans a generation. In the 1990s, for example, federal officials designated the Mexican spotted owl, which lives in multiple southwestern states, as a threatened species. The listing rankled some residents and, according to attorney Blair Dunn, who is representing local ranchers in a lawsuit over the mouse, reduced the land that was available for lumber harvesting and mining.

"It put the community on it's heels and now all that's left there is those ranchers," Dunn told BuzzFeed News. "Spotted owl killed logging and mining."

Tension over the spotted owl continued for decades until, in 2011, residents in Otero County — also ground zero in the battle over the jumping mouse — staged a "tree party" to cut down what they described as overgrowth in the Lincoln National Forest.

Conservationists slammed the event as illegal. Organizers, on the other hand, said that efforts to save the owl had killed off the area's lumber industry and turned the forest into a fire-prone tinder box. U.S. Rep. Steve Pearce participated in the event and delivered a speech calling for smaller government — a rallying cry at several similar protests that collectively have been referred to as the "Sagebrush Rebellion."

It was into this fraught environment that the conflict over the jumping mouse began to pick up steam in recent years.

The push to get the mouse protected as an endangered species was led by WildEarth Guardians, a conservation advocacy group working in the American West. The group's efforts began in earnest in 2008 when it asked the feds first to reduce livestock grazing areas and then to list the mouse as endangered.

WildEarth Guardians was later joined by other conservation groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity, in lobbying for the mouse's protection. On June 20, 2014, those efforts finally paid off when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the rodent as an endangered species.

Wally Murphy, a New Mexico field supervisor of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, told BuzzFeed News the designation followed two decades during which the mouse population dwindled by about 80% thanks to "historic livestock grazing practices." The population decline left the existing mouse populations so isolated that they no longer have contact with each other.

"We’re losing genetic diversity," Murphy added. "We need to restore that connectivity to restore genetic diversity."

"It's a canary in a coal mine."

Bryan Bird, a wild places program director for WildEarth Guardians, told BuzzFeed News there are several reasons to protect the mouse. The mouse, he said, lives in tall grasses along rivers that, downstream, are used by humans. The health of the mouse population therefore indicates how healthy the watershed itself is.

"It's a canary in a coal mine," Bird said. "This is what we call an indicator or a bellwether animal. It will indicate if the human race will survive in western states that are dry and get their water from snowmelt."

According to Bird, the problems with grazing — both from cattle and non-native elk in the region — include animals trampling the mouse's habitat and polluting the water.

"Basically the system is being degraded," Bird said. "It's like if you had a filter on your refrigerator. When the mouse has its habitat in place we know the rivers and the streams are acting as they should in filtering our water."

Bird praised the recent land designation, but added that it is "not enough habitat to save this species."

The coalition that pushed for the listing of the mouse as an endangered species also included the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, an organization that advocates on behalf of hunters and fishermen. The group's executive Director, Garrett VeneKlasen, echoed the arguments of WildEarth Guardians, calling the mouse a "natural barometer" of the eco-system's health. VeneKlasen argued that protecting the mouse would ultimately benefit everyone, including ranchers.

"We started standing up for the mouse because what’s good for the mouse is good for the animals that our members are interested in pursing," he said. "It benefits everyone. It even benefits the public land cattle."

But right or not, the efforts to protect jumping mouse habitat are prompting significant controversy in surrounding communities. Early on, in May 2014, Otero County commissioners bucked federal authority by voting to have Sheriff Benny House "immediately take steps to remove or open gates that are unlawfully denying citizens to their private property rights." The gates had been put in place by the feds. In a testament to the deep-seated angst in the region, House, perhaps taking a cue from other western sheriffs, said in 2011 that he did not recognize Forest Service authority and threatened to arrest the agency's law enforcement officers, according to court documents.

Eventually, a group of ranchers and other agricultural industry groups filed a lawsuit over the jumping mouse protections, arguing that the Forest Service relied on faulty studies, violated rules, and was trying to prevent cattle grazing.

"We feel that at this point in time that the federal government is completely oppressive."

Dozens of area ranchers said in statements they had never seen a New Mexico meadow jumping mouse, and that fencing off the area would "have drastic negative effects on our communities and will serve to destroy our multigenerational agricultural heritage."

Dunn, who is representing the ranchers and agricultural groups, said cutting them off poses a significant threat to their livelihoods.

"They're staring down the barrel of losing much needed access to water for their cattle," he told BuzzFeed News.

Murphy, of the Fish and Wildlife Service, countered that the objective never was to cut ranchers off. National forests included in the designation have not asked ranchers for any reductions in their number of cattle, he said, and officials have met with those affected in order to hammer out solutions such as leaving pathways for cattle to access water.

"We do everything we can to make sure those activities can continue on public land," Murphy said.

Lucero disagreed, saying federal representatives have failed to meet with ranchers or explain what is happening, even after the ranchers have "always stayed respectful and civilized."

Case in point: Lucero said that when he and other ranchers visited the pasture in 2014 they found Forest Service employees trying to drive posts into soft, swampy soil — which wouldn't hold up over time. So, Lucero said, the ranchers offered advice, and before long were actually helping the feds carry fence posts.

Lucero and others in October 2014 as federal authorities fence of meadow jumping mouse habitat.

That day in the New Mexico mountains things remained cordial and, thanks to a judge's ruling, the ranchers believed the fence would be coming down a year later. That didn't happen, Lucero said, and the barrier remains in place. With the new habitat designation, and the traditional spring grazing season upon us, the ranchers feel like they are in a state of limbo.

"We’re one month away from putting our cattle back on that forest and we still have no answers about how it’s going to work," Lucero, who has permits to graze about 42 cattle on public land, said. "How are you supposed to make a decision on your livelihood in one month?"

That frustration is widespread, according Caren Cowan, executive director of the New Mexico Cattle Grower's Association.

"We feel that at this point in time that the federal government is completely oppressive," Cowan told BuzzFeed News.

Cowan said that the number of ranchers who will be directly affected by the jumping mouse case, at least in the short term, will be small. Still, the situation has the attention of the industry and numerous small communities because "every year there's one or two regulations that are more damaging. Over this last year it's been worse than ever."

"It just seems to come in waves and the waves are getting closer together," she added.

John Hernandez — who runs 200 head of cattle in the region — agreed, saying that some of his neighbors may be driven out of business.

"Whole families are going to be affected," Hernandez said after a day of working on the ranch with his 14-year-old son. "Which is going to piss them off, which is going to create a very negative attitude toward the federal government."

Hernandez criticized the process by which animals become protected species, saying it was highly politicized and that some officials "don’t care whose lives are destroyed."

These tensions are not unique to New Mexico. When Cliven Bundy faced off against the feds in 2014, the conflict was rooted in a dispute over cattle grazing. When Bundy's son, Ammon, led a militia takeover of a federal wildlife refuge in Oregon, the occupiers repeatedly criticized the government's land use policies. Numerous other, lower-profile protests have flared up elsewhere across the west in recent years, and Dunn connected them to what is happening now in New Mexico.

"Everybody is really getting very upset."

"Around the West, the stuff that went on in Nevada, the stuff that went on in Oregon, those are extreme outcroppings of what is really a growing rumbling," Dunn said, referring to recent Bundy-led standoffs. "Everybody is really getting very upset."

But there's an important distinction: the people angry with the government in New Mexico are not facing off with federal law enforcement in armed standoffs. If fact, both Dunn and Hernandez sharply criticized the Oregon occupiers. Dunn does not expect violence from the people he represents, and said he's told them that breaking the law only hurts their cause.

"We’re not like Cliven Bundy," Hernandez said. "These folks all pay their grazing permits."

For now, both ranchers and conservationists are waiting to see what happens next. Bird said his organization will be watching to see if the feds do enough to protect the mouse. Lucero, who has launched a congressional bid prompted by the land use conflicts, said he hopes the mouse can quickly recover and life as a rancher can soon go back to the way it was.

Others seem merely disappointed, resigned even, that change is on the horizon and shows no sign of stopping.

"I have what I have here and I’d like to pass it on to my son or daughter," Hernandez said. "But, God, there’s no future in it."