FERGUSON, MISSOURI — When you walk down West Florissant, where the protests following the shooting death of Michael Brown happened, you notice a curious thing: It's awfully rough.

Not rough in the sense that a lot of crime takes place here, but rough in the literal sense. There's fractured asphalt, a mishmash of strip malls, and treeless sidewalks that fade gradually into busy lanes of traffic. There are good things happening on the street — shops, restaurants, passionate people — but as a physical space it's indistinct, more like a scorched concrete field than a focused boulevard.

And yet, for much of August the street morphed into a dynamic, if sometimes violent, civic gathering space. It became a kind of public square, which is surprising because other recent protest movements have been tied to spaces that were already intentionally civic: the Egyptian revolution in Tahrir Square; the Ukrainian revolution in Independence Square; Occupy in Zuccotti Park.

But there is no equivalent space in Ferguson. Not even close.

Since the death of Michael Brown, there have been two narratives about space in Ferguson: stories about the battles and street protests, and stories of poverty and segregation that discussed longer term issues.

Urban planners say that a series of physical conditions that exist in Ferguson contribute to poverty, and those same conditions influenced the protests. City design helped created a powder keg. As engineer Charles Marohn put it, "The fact of the matter is it's a placemaking issue. It's the way these places were built."

Here's why:

The history of a city that makes people poor.

One of the most important things to know about Ferguson is that the way it was designed contributes to its residents' poverty.

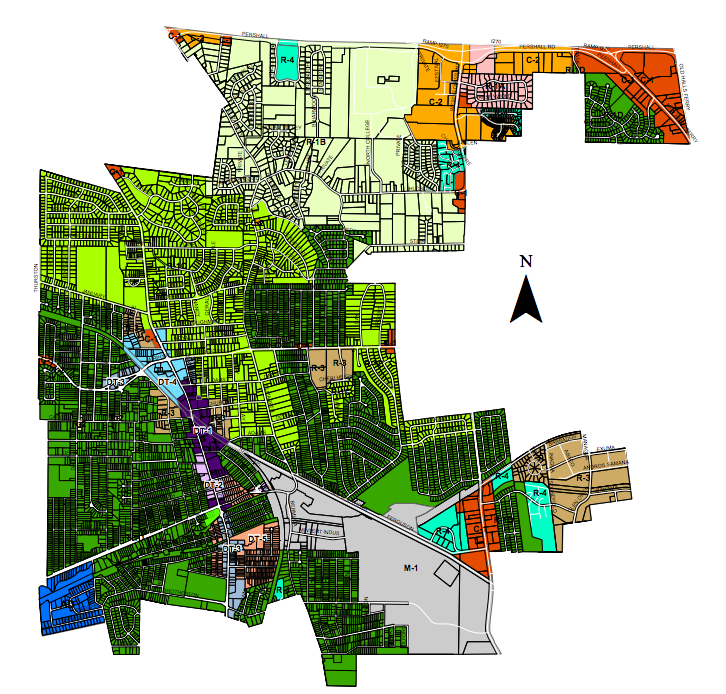

To understand why, we have to go way back to when the space within the city was formed. Ferguson was incorporated in the 1890s, but really took off in the 20th century. The city, particularly the area around West Florissant, bears the hallmarks of post-World War II suburbs: Single-family homes proliferate in residential areas; strip malls and parking lots dominate commercial sections. Those two types of development rarely mix, and everything is designed to be accessed by car.

Ferguson is also part of a fragmented municipal landscape, where dozens of tiny individual cities make up the sprawling St. Louis metro area.

According to University of Iowa professor Colin Gordon, the formation of these numerous little cities and sprawling suburbs were driven by race. Gordon said that the cities began as neighborhoods governed by "deed covenants," rules that explicitly kept out minorities. "They could say to their face, 'I'm not going to sell that house to you because you're black,'" Gordon explained.

The courts eventually put the kibosh on using covenants as segregation tools, but developers responded by breaking their neighborhoods off into separate municipalities and using zoning laws to maintain segregation. That continued into the 1950s and '60s, until the Civil Rights Act of 1968 made housing discrimination illegal. What followed was a period, beginning in the 1970s, during which blacks in the St. Louis area began moving into the previously all-white suburbs.

"For the first time in the early to mid-1970s," Gordon said, "it became possible for black families to do what white families did a generation earlier, which is flee a crumbling neighborhood for one with better schools."

Whites already living in cities like Ferguson responded by fleeing to still further-flung and newer suburbs, though Gordon said that the remaining leadership is a vestige of that bygone era. "The white power structure is hanging on by their fingernails even though their demographics are changing under their feet," he said.

Cities like this are expensive to build and maintain.

Cities built by what Gordon described as an "early and formalized system of segregation" run into a lot of problems. One of the most obvious is that they begin to run out of money. The cities begin to have lower tax revenue, as property values decline and incomes drop, Gordon explained, and an aging city means the costs of upkeep on infrastructure goes up.

"They're high cost and low tax revenue," Gordon said.

In Ferguson, that produced a physical environment that was "designed to fail," according to Marohn, who is also president of Strong Towns, a planning and development nonprofit that focuses on financial resiliency in American towns.

In a conversation with BuzzFeed, he said that "auto-oriented development" disperses low numbers of people across areas that require huge ongoing investment for things like streets. Designing cities for cars, rather than people on foot or public transit, is both inefficient and alienating for residents, he added.

In an article on Ferguson he broke down some of the numbers on Ferguson's spending, then came to a bleak conclusion:

This type of development doesn't create wealth; it destroys it. The illusion of prosperity that it had early on fades away and we are left with places that can't be maintained and a concentration of impoverished people poorly suited to live with such isolation.

Marohn went on to describe this kind of development as "despotic" because it saps municipal funds, reduces residents' transportation options, and limits economic opportunity. He added that American suburbs tend to pass through roughly 25-year phases. In the first phase, they see robust growth, followed by "a kind of hanging-on period," and finally after 50 or so years they hit a "rapid decline phase." Ferguson is in the decline phase.

"The economic segregation is starker now than it has ever been."

Driving through the neighborhoods around West Florissant, one thing becomes clear: There's a certain degree of uniformity when it comes to the homes. Many of the buildings clearly come from the same general time period and were done in a limited number of styles. That's not unique, but it is problematic, various planners told BuzzFeed.

When entire neighborhoods are constructed at once, they also tend to deteriorate all at once. Steve Mouzon, an architect who has written extensively about durability, said building styles used in many suburbs produce structures that aren't meant to last. The result is that entire neighborhoods can rapidly decline all at the same time. "If it does fail, what fails with you fails with your neighbor," Mouzon said. "I think it tends to create a sense of hopelessness because everything is failing all at once."

Gordon said that the uniformity seen in Ferguson's neighborhoods also contribute to segregation because when every house is the same size, only people in one particular income bracket end up living there. "You don't have the leavening of having people of different incomes," he explained. "The economic segregation is starker now than it has ever been."

The result is that there are poor towns filled with poor people and rich towns filled with rich people. And in the St. Louis area, Gordon added, economic segregation tends to mean racial segregation as well.

"The rotting ring of suburbia."

There are an array of issues stemming from the way Ferguson was built that have sent it into decline. And these issues trickle down into the lives of residents.

Karja Hansen — an alumna of the acclaimed planning and architecture outfit Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company — agreed, characterizing suburbs in decline as tragic places. "It turns into a center of poverty," she said. "It's called the rotting ring of suburbia."

Of course, the overall picture in Ferguson is exceedingly complex, but in any case none of the experts who spoke with BuzzFeed were at all surprised that a suburb of Ferguson's age and composition would be in decline. Rather, they all said, decline is the logical conclusion of decisions made when Ferguson's neighborhoods were being built.

In addition to the many complaints raised by protesters about race and policing, recent research shows Ferguson has experienced a sharp rise in poverty just over the last decade. The Brookings Institute went so far as to describe the city as "emblematic of growing suburban poverty."

During the protests following Michael Brown's death, these economic problems were a potent subtext on West Florissant, as one protester explained:

Encouraging for-profit policing.

When a city like Ferguson runs into these kinds of problems, it has to find more creative ways to make enough money to survive.

One answer has been to turn the municipal justice system into a funding mechanism.

Reports on Ferguson reveal that the city brought in about $2.6 million from court fees in 2013 — making those fees one of the city's most significant revenue streams. Ferguson police also issued more than 14,000 traffic tickets in 2013. That's 67% as many tickets as there are people in Ferguson. If those tickets were evenly distributed (which of course they aren't), it'd mean that two out of every three people in Ferguson had been ticketed.

During the second week of protests, BuzzFeed spoke at length with two men, Ray Brown and Tony Louis, who talked about what they said was a justice system that profiled black men specifically to extract exorbitant fees. When BuzzFeed subsequently asked dozens of other protesters and community members about similar experiences, nearly everyone confirmed that they too had been targets. The result was a deep sense of resentment in Ferguson over the justice system.

"This is a huge, huge issue," Marohn said. "It undermines not only the finances of the community, but it breaks down the bonds between officials and citizens. They're adversaries."

Cities need civic space to serve as a social and political "release valve," but Ferguson, by design, lacks any such space.

Poverty and desperation are two results of the way Ferguson was designed. An utter lack of civic space is another.

Drive through the neighborhoods — and they are designed for driving, not walking — and you see houses, shops, maybe even a park or a school. But there's nothing remotely close to a genuine civic space like those used by other recent protest movements. That can erode social connections, according to journalist and Happy City author Charles Montgomery.

"When people lack common spaces for exchanging ideas," he said, "in some cases we see violence spill into the nooks and crannies of the city."

Marohn added that social and civic spaces function as a kind of outlet: "You have to have a town square," Marohn said. "Basically old traditional cities are designed to have some release valve. People come together, they congregate. When they get ticked off they can protest. In suburbia, there is no town square."

Adding to the problems related to a lack of civic spaces, the public area that does exist in Ferguson is poorly designed. Along West Florissant, sidewalks are almost indistinguishable from the parking lots and the street — sometimes cars literally park on the sidewalks. They lack any shade, which in the brutal summer heat makes them pretty close to unusable. Marohn describes this kind of street as a "stroad" — a "ridiculously dangerous" hybrid between the smaller streets cities should have internally and the major roads that should link cities together.

Further into the neighborhood conditions improve — the streets are quieter and towering oaks block out some heat — but are still not ideal. "Are we surprised that two men would be walking in the street here?" Marohn writes, referring to Michael Brown. "If they were going to be on the sidewalk, they would need to march single file."

All of these factors — poverty, segregation, a lack of civic space — primed Ferguson for unrest.

Marohn described the physical environment in suburbs like Ferguson as a confluence of horrible things. "We've created these pockets of desperation and essentially designed them with the conditions to make it as explosive as possible," he explained.

It's curious and tragic, then, how the events in Ferguson played out. They began with with Brown essentially jaywalking — an offense that Hansen, echoing a 2012 article in The Atlantic Cities, described as invented by car companies — and evolved into demonstrations in the streets, or some of the very places that caused problems in the first place.

None of this went unnoticed by police; during the second week of protests, officers managed to control the crowds by gradually forcing people off of the newly occupied space and onto sidewalks. The gif below (crudely) illustrates this tactic. The police, represented in red, would gradually move into the crowds, represented in green, eventually forming walls of officers and vehicles in the streets and parking lots.

The result was that people were allowed to continue their marches, but not in the areas that most represented defiance.

These protests can be read a lot of ways, but it's hard not to see them at least in light of other American movements. During the civil rights movement in particular, people reclaimed symbolically laden spaces from which they were banned. Bus seats, restaurants, drinking fountains, schools. In every case, the protest hinged on who was allowed into which space. Yes, civil rights also happened in the streets, obviously, but so far Ferguson is almost exclusively street-based.

There are other cities that are primed for unrest because there are other cities with physical compositions similar to those in Ferguson.

The violence in Ferguson has calmed, at least for the moment, and what remains is a city like many others in America. The experts who spoke with BuzzFeed said that could spell trouble, with the same kinds of forces that contributed to poverty and isolation in Ferguson providing kindling for social unrest in other places as well. "Here's the scary thing," Mouzon said. "The problems that Ferguson faces are more like the problems that other American cities face than unlike them."

Special thanks to Hazel Borys of Placemakers for background on this article.