Have you ever heard the Kidz Bop cover of Nicki Minaj’s “Starships”? It’s so strange, it became something of a meme. The musical arrangement is just familiar enough, like one you’d hear at a karaoke bar. Then the vocals kick in: Minaj’s petulant rapping has been replaced by several chirpier voices. If you couldn’t tell they were children, you definitely can once you realize the line “We’re higher than a motherfucker” has been replaced with the bland but on-brand “We’re Kidz Bop and we’re taking over.”

But there’s no Kidz Bop version of, say, “WAP,” no sweetened version of that driving beat or child-safe alternative lyrics. If you’re familiar with the company, which PG-ifies pop hits for the early-elementary set, you can probably see why. Kidz Bop — technically stylized as KIDZ BOP — has been in business for decades. While their task is sometimes as easy as swapping out swears, in the case of Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s terrifically profane ode to women’s sexual desire, there was no way it could be softened. Still, Kidz Bop-esque parodies of the hit proliferated across the internet, as did a satirical news story about a Kidz Bop writer suffering a nervous breakdown while trying to write a clean version of it. Perhaps there’s no better sign of total cultural saturation than this: Even the things you don’t do can spark a news cycle.

But to its detractors, Kidz Bop is an unholy compromise between children’s entertainment and adult culture.

This October, Kidz Bop turns 20. Since its first album, KIDZ BOP, which opened with a cover of Smash Mouth’s “All Star” and closed with Sixpence None the Richer’s “Kiss Me,” the franchise has been one of the recording industry’s quietly enduring success stories. In an era that has seen the music business all but collapse in on itself — declining album sales and revenue, streaming disrupting the traditional distribution model — Kidz Bop has managed to thrive. With over 21 million album sales and 24 albums that debuted in the Top 10 of the Billboard 200, the “Kidz Bop Kids,” as the changing cast of young performers is credited, have had more Top 10 albums than anybody save for the Beatles, Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, and the Rolling Stones.

Kidz Bop has become a trusted guide to pop for parents without the time or energy to keep up with music but who still want to hear today’s hits minus any overtly sexual, drug-related, or violent lyrics. But to its detractors, Kidz Bop is an unholy compromise between children's entertainment and adult culture, strip-mining each category for its worst qualities and Frankensteining them together, all so families can unite to listen to, say, a cloying rendition of Lizzo’s “Truth Hurts” so lyrically incoherent — “You could’ve had a good friend, noncommittal” — you wonder why you’re listening to it at all.

Behind Kidz Bop’s pop chart domination is the alchemy of an unassuming idea meeting the opportune cultural moment, and a surprisingly resilient formula in a volatile, unforgiving marketplace. But the franchise’s success also raises some complicated questions. How much of a parent’s identity should be sidelined in the interest of creating a safe environment for children? What does it mean for a song to be “appropriate” for kids? And what gets lost when art is sanitized for its youngest potential consumers?

Cliff Chenfeld’s children are adults now. But in the late ’90s he spent weekend after weekend at kids’ birthday parties, where the soundtrack was basically Barney and Raffi on repeat. By 2000, he and his friend Craig Balsam each had three kids under the age of 10, and the sonically beleaguered fathers noticed something: Even the kids in attendance were growing weary of “Baby Beluga.” But while the parents could do without hearing “I Love You, You Love Me” for the thousandth time, they were wary about switching from children’s music to Top 40 radio.

“When I’d talk to my friends about this, they were very flipped out about Britney Spears or Eminem or whoever the artist of the day might be,” Chenfeld told me over the phone.

It was a high time for pop culture panic. The conservatism of George W. Bush’s White House oozed into everything: blaming video games for mass shootings and Britney Spears’ midriff for corrupting girls the nation over. In 2002, BMG Music Group — which was then releasing records by Christina Aguilera, OutKast, Pink, and Amy Winehouse, among others — updated parental advisory labels to specify what was objectionable about the product: strong language, violent content, or sexual content, so concerned were adults with knowing exactly what was in the songs kids were listening to.

To a certain stripe of parent, it felt like modern pop culture was a relentless onslaught of profanity and vulgarity.

Were the pop stars of the 2000s really doing anything substantially more salacious than their forebears? Prince wore assless chaps to perform “Gett Off” at the 1991 MTV VMAs; grading on a curve, it hardly seems like Spears and her pop cohort were shattering any sexual boundaries. But to a certain stripe of parent, it felt like modern pop culture was a relentless onslaught of profanity and vulgarity. Top songs of the late 1990s and early 2000s included Aguilera’s “Genie in a Bottle,” Nelly’s “Hot in Herre,” Sean Paul’s “Get Busy,” and Sisqo’s “Thong Song” — choruses that celebrated barely there underwear and taking off all your clothes were not, perhaps, providing the vibe Emily’s parents were going for at her seventh birthday party.

This glut of graphic content collided with the rise of, well, “I don’t want to say over-parenting,” said Chenfeld. “But parents becoming more involved in their kids’ lives than in previous generations.” Twelve-year-olds who, a decade earlier, would’ve been left to their own devices between the last school bell and dinnertime were starting to carry around cellphones — a new tool in a helicopter parent’s arsenal. And as dial-up modems made way for broadband, the internet became a far more common presence in Americans’ homes; parents were more panicked than ever about their inability to control what their kids consumed. “I think, frankly, we benefited from some level of that,” said Chenfeld. “We certainly saw that going on and tried to create a solution for it… We thought there maybe was a way to split the difference and make both sides happy.”

Chenfeld and Balsam were uniquely situated to do that. Back in 1990, they’d cofounded the independent record label Razor & Tie. (They sold the label in 2018 and no longer have anything to do with Kidz Bop.) The duo issued compilations of hits from the 1970s and 1980s, available via a 1-800 number. (You can still watch an early ad for their first release, Those Fabulous ’70s.) Chenfeld and Balsam had found a niche that nobody else had thought to exploit: Major labels weren’t selling albums on TV, nor were they going into the archives to put all their old material on CDs. Razor & Tie had its own TV marketing department, bought ad space on newer channels, and made a killing; one compilation, Monster Ballads, sold more than 3 million units.

In 2000, Chenfeld recalls, Razor & Tie noticed another revenue stream the major labels were leaving unexplored: the children’s market. “It wasn’t particularly sexy,” Chenfeld said, but neither was shilling the greatest hits of disco, and that had worked out pretty well. “Our company was always one that was a little bit outside the music business mainstream.”

To pick the first batch of Kidz Bop songs, they scoured the pop charts, plucking upbeat, danceable, or sing-along hits from recent years: “I Want It That Way” by the Backstreet Boys, Blink-182’s “All the Small Things,” the insanity-inducing earworm “Blue (Da Ba Dee).” Though you might think the rights to popular music would be expensive, the Kidz Bop project is actually pretty cheap to produce. For a cover, you only need to pay the holder of the composition copyright for the “mechanical license,” and the industry standard licensing fee is nine cents per song sold. You don’t even need the artist’s permission to cover their work. When asked, Chenfeld wouldn’t reveal anything about how Kidz Bop rewrote song lyrics while he was there; current Kidz Bop management also declined to get into the details, saying only that they largely rely on the clean radio versions of the songs.

Early Kidz Bop albums were performed by adults, with kids occasionally chiming in for background harmonies and choruses. But before long, Kidz Bop landed on the winning strategy of having young people take over lead vocals. “I think it’s really powerful for a kid to hear another kid singing these songs,” said Mike Anderson, who has been with Kidz Bop since its inception and is currently senior vice president of music. “It makes this pop star world accessible, to see kids like you being a part of that.”

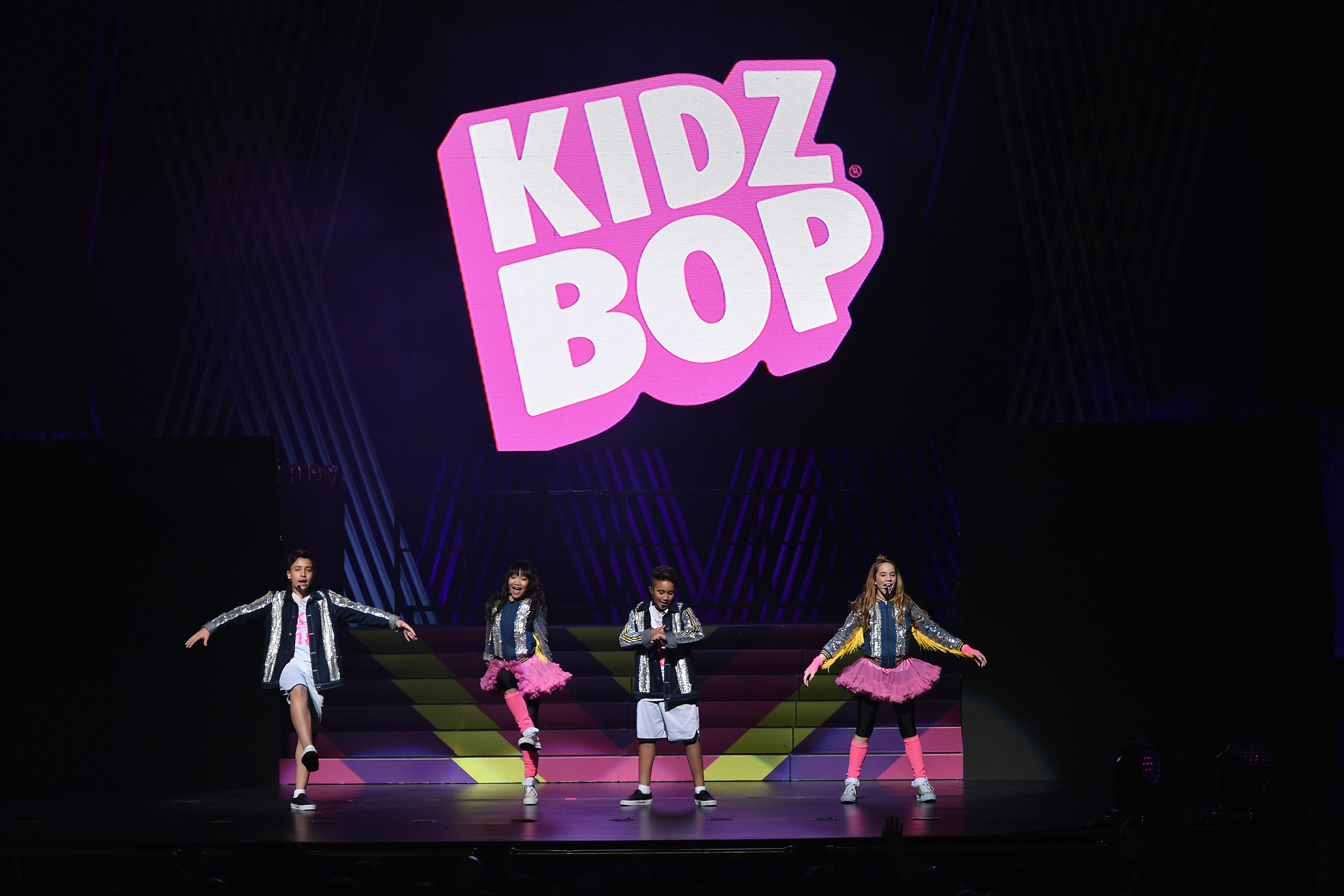

After about seven years, Kidz Bop shifted from the nameless, faceless kid model to the system they’ve got in place now, which works like Menudo: Nationwide casting calls produce their new hires, who stick around until they age out. These tweens tour, appear in music videos, and have public, first-name-only profiles, like Bachelor contestants. The current American lineup is Layla (a 13-year-old “math-whizz” who loves the Pittsburgh Penguins), Alana (a 12-year-old from Texas who played young Miranda Bailey on Grey’s Anatomy), Ayden (an 11-year-old from Texas who loves dance and koalas), and Egan (a 13-year-old classically trained dancer from Ohio). Kidz Bop has even caught a couple of kids on their path to stardom; Zendaya was a Kidz Bop kid, as was Disney Channel star turned Sabrina love interest Ross Lynch.

Just as they had with the retrospective compilations, Razor & Tie produced their own Kidz Bop advertisements; if you were up late watching Nick at Nite in 2000, you probably caught the first one. Over footage of children dancing, hula-hooping, and turning cartwheels across a field, an offscreen man narrates, in that Mr. Moviefone baritone, “These are the songs kids are singing! They’re great for parties, driving in the car, or just about anything.” The price: two CDs for $21.99 or two cassettes for $19.99, plus $5.95 shipping and handling.

Most adults can probably agree on what qualifies as profanity. But “appropriate” is another concept altogether.

Chenfeld and Balsam had hit on a sweet spot: Kids who didn’t like baby music anymore could graduate to cooler stuff, while parents could hit play in peace. The first album went gold, as did Kidz Bops 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, and a 2002 Christmas album. From 2005 to 2016, with rare exceptions, Kidz Bop releases consistently debuted in the Top 10. When Kidz Bop 21 came out in 2012, it debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard album charts — second only to that other 21, by Adele. By 2009, Bloomberg was calling Kidz Bop “the most underrated force in American music.”

In recent years, Kidz Bop has expanded into new territories beyond the US, recording in five different languages with international casts of kids and launching a SiriusXM station and a YouTube channel. “There is a built-in audience for this franchise that will buy any Kidz Bop CD the week it comes out,” said Chris Molanphy, chart analyst, pop critic, and host of the “Hit Parade” podcast. “And you have to imagine there are parents who are buying this thing as a Good Housekeeping seal of approval: My kids will listen to it, it’ll have current pop on it, but I won’t be appalled by the lyrics.”

What, exactly, is the average parent appalled by? Most adults can probably agree on what qualifies as profanity. But “appropriate” is another concept altogether.

When Kidz Bop released its 30th album in 2015, Slate noted that “the brand is becoming increasingly, oddly conservative,” pointing out that the edits had become more stringent over the prior decade, at times capriciously so. Even the “red lips” mentioned in Taylor Swift’s “Style” and “Bad Blood” were too scandalous to survive the child-friendly edit — though in the 2001 Kidz Bop cover of Ricky Martin’s “Livin’ La Vida Loca,” “devil red” lips and the comparison to “a bullet to your brain” were left intact.

In 2011, when a cover of Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” was included on Kidz Bop 20, it had lost all references to being gay or trans and people who are “black, white, beige.” The Kidz Bop versions of the video and the song have been wiped from the face of the internet, even though when the album was first released, “Born This Way” was the first track listed. (When asked what happened to the song and video, Kidz Bop responded: “Like many brands, we’ve evolved over the last 20 years, and continue to expand globally, celebrating diversity in pop music around the world. At our core, we believe in the importance of spreading inclusivity and kindness through our music and videos, especially to young children everywhere.”)

The end result is music that arrives from some context-free universe.

Though Kidz Bop says their fan base includes families from all over the country and political spectrum, their cover versions seem to spring from very traditional sensitivities about what kind of art is “safe” for impressionable minds. The end result is music that arrives from some context-free universe; the artists themselves are exiled entirely.

Eric Harvey, a music reporter and the author of Who Got the Camera? A History of Rap and Reality, didn’t have a problem with Kidz Bop on his first listen to their cover of Kelly Clarkson’s “Since U Been Gone” back in 2008. It reminded him of other projects where children covered adult music, like the Langley Schools Music Project from the 1970s, which brought out an innocent emotional quality in songs by the Beach Boys and David Bowie. “But you dig in a little deeper and it’s like, Oh no, this is literally the opposite of that.” He realized Kidz Bop had another, more artless ancestor: Muzak.

“It’s what the Muzak corporation does with pop songs: You strip out all the lyrics and make it palatable to people in shopping malls, elevators, and doctors’ offices,” Harvey said. “Music people hate Muzak. And Kidz Bop reminds me of Muzak, but for kids. You’re taking a piece of popular art and you’re often stripping it of what makes it art.” And in some cases, he said, “taking out the words that the artist originally put in there.” “It’s kind of a mercenary version of pop music whittled down to its core,” he said.

Harvey traces that conservatism back to the 1980s, a period of “very profitable fears about what popular culture was doing to our children’s minds.” He said “moral entrepreneurs” like Tipper Gore and James Dobson of Focus on the Family fame painted pop music as a kind of toxin. “They were framing it, really, in these terms: It’s a health danger to your kids to be exposed to this.”

Making popular music less edgy is a longtime American tradition, said Molanphy. He pointed to Mitch Miller, a bandleader and record executive who hosted Sing Along With Mitch on NBC in the 1950s and released albums under the Sing Along mantle. Miller famously loathed rock and roll — while at Columbia Records, he declined to sign Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly — and with his show and albums “was providing squeaky-clean family fun,” said Molanphy. “These albums sold like hot cakes ... [Kidz Bop] is really a 21st-century reboot of Sing Along With Mitch.”

Another effect of this sanitation is diluting, or even erasing, a song’s relationship to genre. “There’s a subtext, always, of anti-rock and, currently, anti-hip-hop [stances],” Molanphy said. Though Kidz Bop covers Black artists — their catalog reflects whatever is on Top 40 radio — Harvey pointed out the rap verses from pop songs often don’t survive in the covers. For example, there’s no Snoop Dogg verse in the Kidz Bop “California Gurls” and no Ludacris verse in the Kidz Bop version of Justin Bieber’s “Baby.” “It definitely does seem like what they’re doing here, at least sonically… is bleaching all of the color, so to speak, out of this music.”

Kidz Bop provides a “safe” listening experience for families — but does it also deprive kids of something else? Isn’t a meaningful, formative part of childhood to be exposed to art that goes over your head, grasp for it, and understand it anew as you mature? When Harvey was growing up, he said, “I was listening to what my parents were listening to,” and when confusing content arose, he’d ask them what it meant. “It just seems like there is a lot of stuff that is in popular music that could really spur interesting discussions about growing up, about sexuality, about any number of issues. The whole Kidz Bop enterprise just seems remarkably conservative on that front.”

Eric Rasmussen, chair of early childhood music at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore, once told PBS Kids, “Kids’ CDs that are geared toward children are not necessarily very healthy music for children to be listening to. They are often poorly produced, sung by children singing as if they are adults, and in major keys only.”

But Sasha Junk, the president of Kidz Bop, said that most families listen to different types of music, and that Kidz Bop “can live in that ecosystem.” It’s easy for adults to mock Kidz Bop, but kids are the target audience. “If you give a kid a choice between Kidz Bop or some grunge or Gen X rocker that you love, they’re going to choose Kidz Bop until they age out and their tastes evolve,” she said. (Junk’s comment reminded me of that Onion article “Cool Dad Raising Daughter On Media That Will Put Her Entirely Out Of Touch With Her Generation.”)

As Junk sees it, “We’re the introduction to pop music for hundreds of thousands of kids. We’re their first-ever concert. We’re helping them develop a love of music.”

I wanted to know what parents who think of themselves as discerning consumers of kid content had to say about Kidz Bop. Author and journalist Drew Magary, who wrote the Deadspin series “Why Your Children’s Television Program Sucks,” was game to oblige.

“I knew they were kids. I was just hoping they would have better taste.”

“As you raise kids, you’re introduced to all these bizarre and inexplicable and ultimately hilarious ecosystems, all these corners of the parenting universe you had no idea about before,” he said. Though Magary knew his kids would like entertainment specifically tailored to them, “I didn’t expect them to like every goddamn Disney Junior sitcom that is somehow worse than Saved by the Bell.” he said. “I knew they were kids. I was just hoping they would have better taste.”

When Magary’s daughter was still listening to the Wiggles, Laurie Berkner, and Justin Roberts, his wife brought home Kidz Bop 22. (Tracks include “Call Me Maybe,” “What Makes You Beautiful,” and “Starships.”) He deemed the whole package “pretty tolerable” and “not an active evil,” adding, generously, “The Kidz Bop cover of ‘Moves Like Jagger’ is better than the original.”

Plus, it worked. Magary’s daughter liked the album, then moved on to regular pop music. But his two younger children skipped the Wiggles and Kidz Bop entirely. Because Magary and his wife had a bit of a parenting epiphany: “We realized you can just start playing normal pop music. Because normal pop music right now is not designed for 40-year-olds. It’s Olivia Rodrigo; it’s grade-school shit. Apart from curses, which are already bleeped out...you can get them started right away.”

It reminded him of how their kids’ diets evolved. When their daughter was younger, they fed her special watered-down cereal for a full year. But when their sons were the same age, they fed the boys normal food, in smaller and/or mushier pieces. “You realize that these progressions to get kids up to a certain level of consumption of music, of food, of anything else,” he said, “it doesn’t really have to exist.” Children, it turns out, might not have such particular needs and sensitivities. They can be just like us.

The 2021 Kidz Bop Live tour was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but they hope to be back on the road as soon as it's safe. In the meantime, they’re releasing new videos regularly; in late September, they posted a video for their take on the BTS summer smash “Butter.” But for an enterprise that is based on following what’s already popular, it’s fitting that the group’s trajectory also matches that of the mainstream pop artists they cover: Sales just aren’t what they used to be. Looking at the last five years of charts, Molanphy said that Kidz Bop still does “OK,” albeit on a smaller scale. “But its chart performance has gone from solid to anemic as Spotify has taken over the music business,” he said.

Still, Molanphy said, Kidz Bop has one thing in its favor. It reaches “the last two demographic groups still buying things… older consumers, and the very youngest consumers.” Think of 2014, he said: “When sales had really cratered and the only person still selling stuff was Taylor [Swift] or Adele, the No. 1 album of the year was the Frozen soundtrack.”

If you think Kidz Bop is annoying, it’s probably because you’ve never been forced to listen to the more annoying alternative — kids screaming — or kids singing “We’re higher than a motherfucker.” And ultimately, it probably doesn’t matter to them what naysayers think. Kidz Bop succeeds by being the path of least resistance, and the kind of person who thinks the whole enterprise is lame or lacking in artistry is the last person they’re marketing to anyway; they’re Kidz Bop, and they’ve taken over. ●