“Is that Ed Hardy?”

The clipped accent of the fashion editor halted me on my way to the kitchen. I’d been working at a teen magazine for about a month – my first job out of university – and she’d never actually spoken directly to me before.

I looked down at the top I was wearing. It was bright pink with a skull-and-roses print. Completely bedazzled with studs. I didn’t know if it was Ed Hardy (or who or what Ed Hardy was) but I fucking loved it, and felt pretty chuffed that she’d noticed it. That she’d noticed me.

“I dunno,” I said, smiling. “I picked it up in Thailand.”

“Oh,” she said. “So it’s faux Ed Hardy.”

My smile faltered. There were layers in her tone – in the oh and the faux – that were telling me something I couldn’t quite grasp. I let out a nervous laugh and an “I guess” and walked away, unsure of where I’d gone wrong, only knowing I had.

It wasn’t until years later, when I was well on my way to becoming what my mum not-so-affectionately describes as a “Sydney Person” (read: snob), that I looked back on the incident and saw the startling truth it revealed. What the fashion editor had seen in that moment – and what I never had.

I was a bogan.

TO be Australian is to know “bogan”. When you label something or someone as such, other Aussies know exactly what you mean. And yet it’s an incredibly tricky word to define to foreigners. It’s so rich with nuance that there’s no precise translation, and nothing really captures the complex layers or cuts right to the heart of Australian culture the way “bogan” does.

When the word first entered the national vernacular in the 1980s, it was completely derogatory. While the exact origins of the term remain mysterious, the first recorded use of it was in the surfing magazine Tracks in 1985, in a quote that immediately pegged the people it was describing as unknowing and unfashionable: “So what if I have a mohawk and wear Dr. Martens (boots for all you uninformed bogans)?”

But it was Kylie Mole, the iconic Comedy Company schoolgirl character created by Mary-Anne Fahey, who really brought “bogan” to the masses. Not because she was a bogan (although her “rooly fair dinkum” voice suggests otherwise 30 years on), but because she frequently used the term to insult her archnemesis, Amanda. In 1988, she defined the word in Dolly magazine as a “person that you just don't bother with. Someone who wears their socks the wrong way or has the same number of holes in both legs of their stockings. A complete loser.”

The word “bogan” endured beyond Mole’s popularity. It was added to the Macquarie Dictionary in 1991, described as “a person, generally from an outer suburb of a city or town and from a lower socio-economic background, viewed as uncultured.” And to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2012, where it was defined as a "depreciative term for [an] unfashionable, uncouth, or unsophisticated person, esp. of low social status".

Uncultured, unfashionable, uncouth, unsophisticated, uninformed, unknowing, uncool. Bogan contains a multitude of uns. It’s defined not by what it is, but what it is not.

Uncultured, unfashionable, uncouth, unsophisticated, uninformed, unknowing, uncool. Bogan contains a multitude of uns. It’s defined not by what it is, but what it is not.

In his 2011 book The Bogan Delusion, Dr David Nichols argues that “bogan” as a type of person or group doesn’t actually exist – that it’s a term used to denigrate the working class and define them as the other.

Cultural critic Mel Campbell explored the images of bogans that permeate our pop culture in her 2004 thesis at the University of Melbourne, and later wrote that “we use the idea of the bogan to quarantine ideas of Australianness that alarm or discomfort us. It's a way of erecting imaginary cultural barriers between ‘us’ and ‘them’”.

If you look at (horrific) parodies like Housos and Bogan Hunters, and even relatively affectionate satires like The Castle and Kath and Kim, the bogan figures within are always there to be laughed at, looked down upon, held up as different to us.

Bogan. Un. That which is not. Not sophisticated, not classy, not smart. Not one of us. Not like me.

WHEN I realised I was a bogan – or at least, that I had been perceived as one, because I sure as hell wasn’t comfortable owning a term with all that cultural baggage – I was surprised. Mainly because I had spent most of my life defining others as bogans. As not like me.

Yes, I was from Warilla (‘Rilla to locals), one of the most bogan suburbs in the greater bogan area of the bogan city of Wollongong. But I was from the good side, dammit. The side with the beach, where the big houses were. It didn’t matter that I didn’t actually live in one of them. That my family was working class, or that I spent a large chunk of my time on the “bad” side – the bogan side – at my grandparents’ house.

In my mind, the highway that ran through the middle of town divided us from them. It meant we were different from the people who lived in the housing commission, the ones who were labelled dole bludgers or criminals or bogans.

When I was sitting in a university lecture one day and the professor casually said, “the only way people get out of Warilla is prison or death”, I sunk down in my seat while my friend and fellow Warilla-dweller laughed and muttered that we would show them.

Fast-forward two years and I did “show them”. I had gotten out, and not through jail or untimely death. My parents had instilled in me a belief that I could not only do anything I set my mind to, but that I should. I had become the first person in my family to complete university. I had saved money from working multiple jobs while studying, and travelled overseas for the first time.

I had moved to Sydney, where I began working full time in my dream job in magazine publishing. Where I was wearing my Ed Hardy top, and a faux one at that, and unknowingly signalling all those other uns that mean bogan. Where I gradually shed those ‘Rilla layers and developed an interior life based on inner city mores. Where I dropped the “un” and became knowing.

THERE'S always been a deep sense of shame attached to the word bogan. Part of this is the way that, as Mel Campbell suggests, it captures everything about Australia and our culture we don’t like – that we find unsophisticated and embarrassing. Which is a lot, really – the term “cultural cringe” was created to describe Australia, after all. When A. A. Phillips coined “cultural cringe” in Meanjin in 1950, he used it to describe the way many Australians seemed to believe that cultural products created locally were somehow automatically inferior to works produced overseas, especially in Britain. It’s the type of attitude so ingrained in the Australian psyche that it persists today, although after World War II we came to be more obsessed with American products – and American perceptions of us – than the British.

And so all too often, whenever we see Australian movies, TV, music, art, awards shows, slang, food, and fashion, we cringe. Or rather, when we choose not to see them, because we reject them on face value as bogan (unfashionable, uncouth, unsophisticated) and avoid them altogether. It flattens our culture, this deep-seated cringe.

What the word bogan encapsulates more than anything is Australia, in all its beauty and its ugliness.

Of course, there are other, more insidious aspects of Australian culture we also dismiss as “bogan”. Things like binge-drinking, violence, and racism. But by slapping the bogan label on them we’re still doing ourselves and our culture a disservice. It’s too easy to ignore these issues, to pretend they don’t exist – or at least, that they’re not our problem – when they’re bogan; not one of us, not like me.

Except, of course, that’s exactly what they are. Because what the word bogan encapsulates more than anything is Australia, in all its beauty and its ugliness. And we can’t truly be proud of the former or deal effectively with the latter until we embrace the whole.

IT'S a shift that has already begun. One of the many nuances contained within the word bogan is that it’s not always a negative descriptor. From its derogatory beginnings, it’s adapted and evolved, to the point where it’s increasingly used in a self-deprecating and even warm way. Charles Darwin University linguist Roz Rowen has conducted extensive research into the social discourse around “bogan”, and says that, while the negative connotations still exist, people are frequently using the term to describe themselves and other people positively.

“To be a bogan is really part of Australian culture,” she says. “I found it’s not just the stereotypical ‘Aussie Aussie Aussie’ white Australian, but lots of people [who might have migrated here] who love using the term and embracing it ... It’s kind of a solidarity marker, people bond over it.”

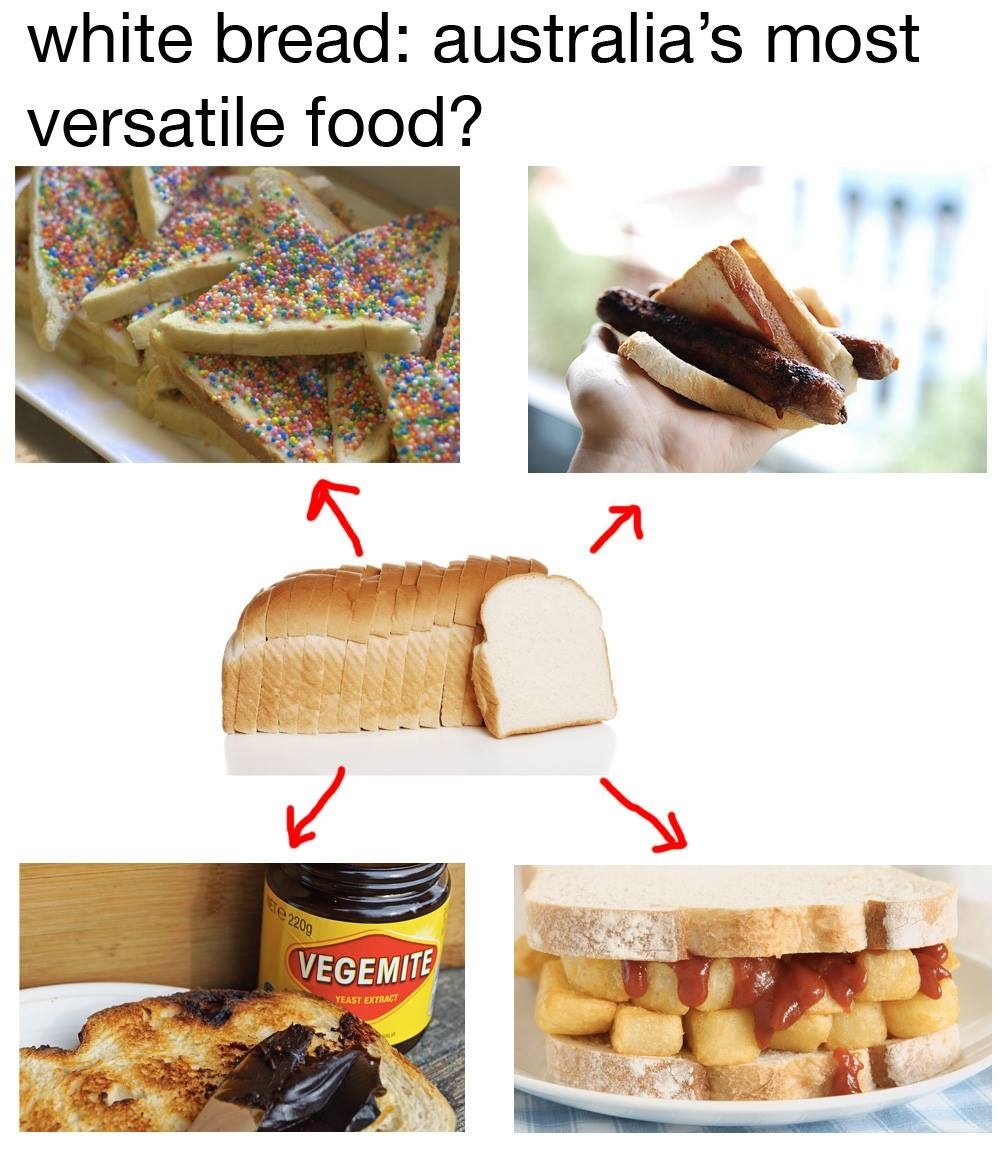

This kind of bogan bonding is evident in the way Australians interact with each other – and foreigners – on the internet. We’ve moved on from the sneering “Things Bogans Like” to memes that push back against the cultural cringe and the notion that Australian culture is non-existent. And we do it through incredibly bogan images and words. Goon of fortune, white bread cuisine, calling mates “cunt” and cunts “mate”, quotes from Kath and Kim, and so many unfashionable, uncouth, and unsophisticated things that we absolutely revel in (albeit with a hearty dose of piss-taking). When it comes to how we’re perceived by other countries, we’re less and less concerned about being seen as a bogan stereotype, and more interested in warning them about the existence of drop bears.

To be Australian is to be bogan, and the many things that word contains.

Let’s face it: I’m a bogan. And you’re probably a bogan, too. Where’s the shame in that?