JUBA, South Sudan — While Americans grapple with the impact of fake news on the election of Donald Trump, in South Sudan, fake news and online hate speech have helped push the country toward genocide amid a three-year civil war, according to independent researchers and the United Nations.

South Sudan's war has divided the country along ethnic lines, pitting followers of President Salva Kiir, who are mostly from the Dinka ethnic group, against fighters under command of former Vice President Riek Machar, who are mostly from the Nuer tribe. In the last year, militia from various other tribes in the country's southern Equatoria region have also taken up arms against Kiir's government.

Tens of thousands of people have been killed, often in bloody ethnic massacres, while more than a million refugees have fled the country and pockets of the country are teetering on the edge of famine.

Although the vast majority of South Sudan’s population has no internet access — the adult literacy rate in the country is around 30% — social media incitement has had an outsized impact largely because it mainly comes from the South Sudanese diaspora, who are held in extremely high esteem back home.

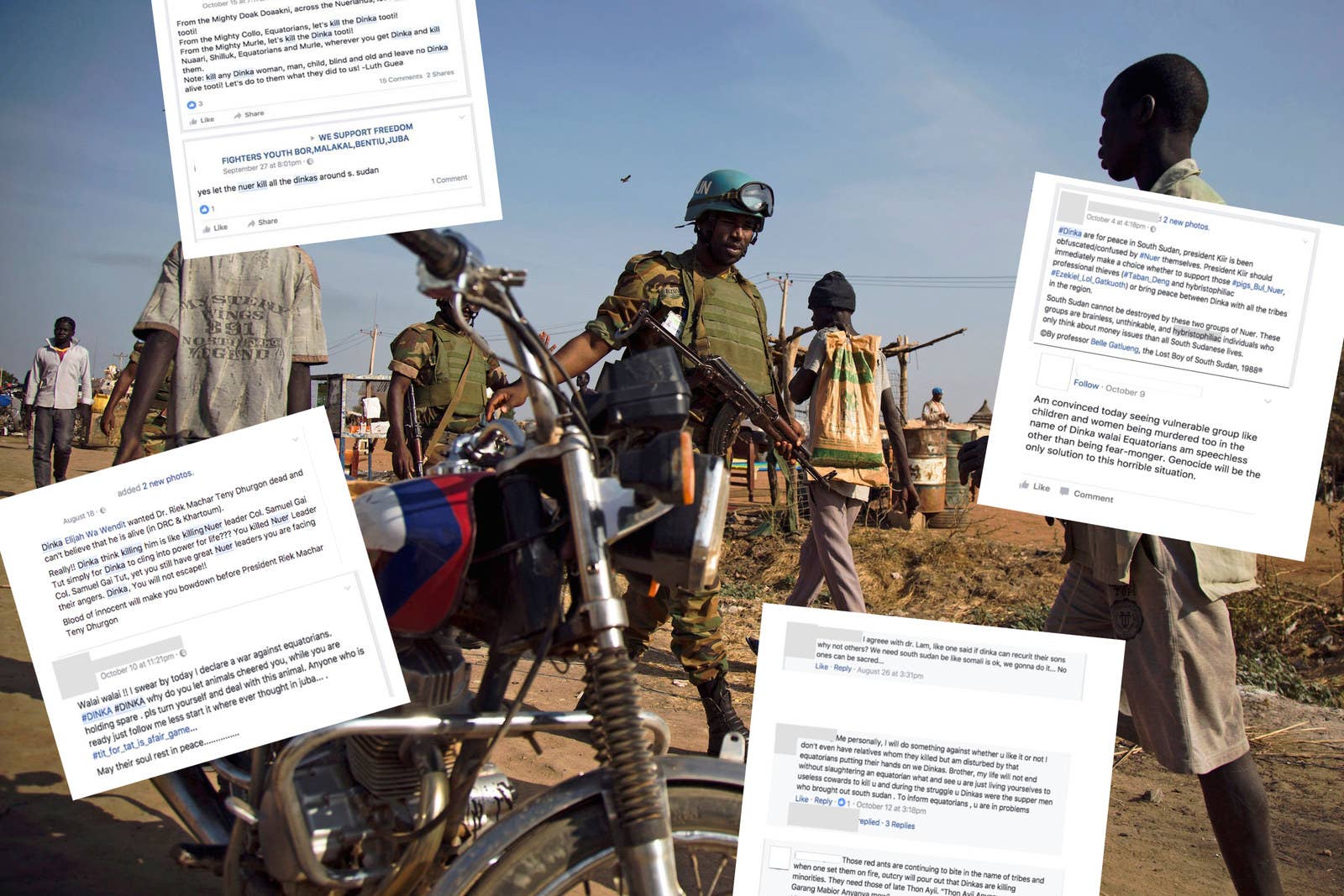

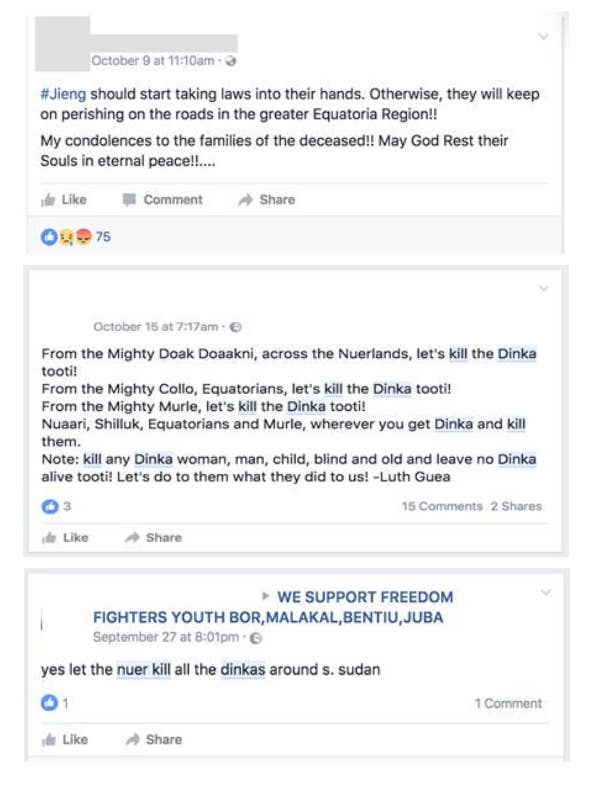

In November, the UN warned that ethnic cleansing is underway and that the fighting could spill into genocide. Government and rebel leaders stand accused of orchestrating Facebook and Twitter campaigns inciting the violence.

"Social media has been used by partisans on all sides, including some senior government officials, to exaggerate incidents, spread falsehoods and veiled threats or post outright messages of incitement," a separate report by a UN panel of experts released in November reads.

It's a situation that has drawn comparisons to Rwanda's 1994 genocide, particularly that crisis’s use of Radio Mille Collines, a local radio station, to fan the flames. And South Sudan’s divide is only getting worse.

"[It] has the potential to create a Rwanda situation massively accelerated through the use of social media," Stephen Kovats, a Berlin-based researcher who helps run #DefyHateNow, an organization tracking and combating online hate speech in South Sudan, said. "Linkages between social media, and word of mouth, and ending up with a gun in the hand or a machete, those are fairly clear."

(#DefyHateNow worked with Peace Tech Lab, a DC-based nonprofit, to help catalogue a lexicon of hate speech terms used by South Sudanese online during the war, including slurs targeting specific ethnicities. They range from “MTN,” used to criticize Dinka perceived to be invading other ethnic groups’ areas by referencing the mobile phone company’s tagline “Everywhere You Go,” to “Dor,” used by some Dinka to depict Equatorians as their slaves.)

To combat the threat, last month the UN Security Council updated the mandate of its 13,000-troop peacekeeping mission in South Sudan to “monitor, investigate and report incidents of hate speech.”

The online networks spreading fake news and hate speech in South Sudan are surprisingly similar to those that have spread like wildfire in the United States. The groups are based abroad, are believed to be for-profit, prey on a general lack of media literacy, and specialize in setting up confusingly named websites to share false news and unverified images.

The Facebook "community pages" populated by members of a single tribe or political group create echo chambers of hate. There are also pages featuring multiple tribes or groups, which turn toxic as different sides clash, mirroring the real-life fighting among the tribes.

"They can post an inciting message: 'You of x tribe, what are you waiting for? Such tribe are finishing us, let us go and revenge!'" said James Bidal, an activist with South Sudanese civil society group Community Empowerment for Progress Organization, which monitors online hate speech. "People read these messages and react on the ground."

According to Bidal, when a trusted diaspora “influencer” posts a comment on social media, the few people online in South Sudan who see it may quickly share it by word of mouth with the offline community. “They take the message very seriously and they keep spreading," he said.

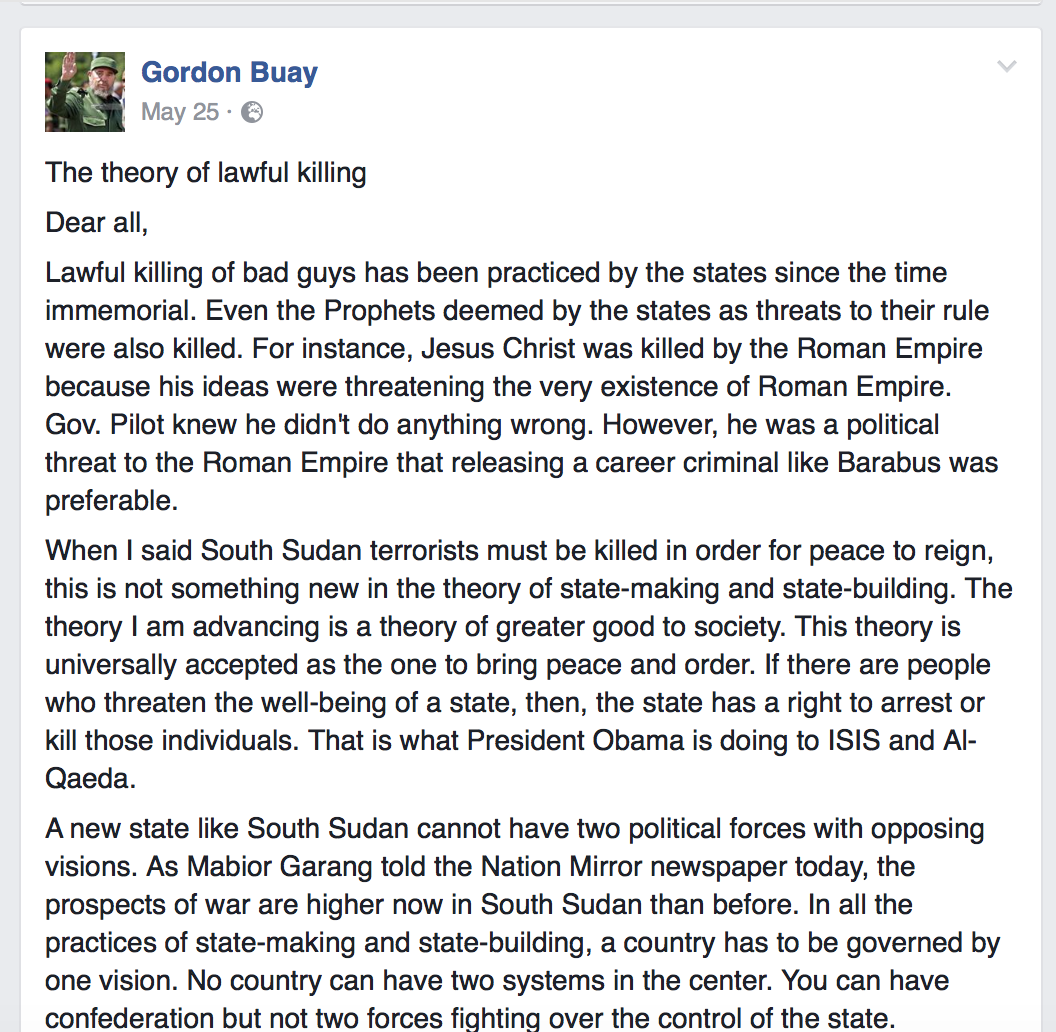

One of the most prominent influencers among the diaspora is Gordon Buay, a South Sudanese diplomat who holds a dual citizenship with Canada, and works at South Sudan's embassy in Washington.

In May, Buay published a series of Facebook posts claiming the government had the right to kill people in the country's Western Bahr el Ghazal and Equatoria regions, where new rebellions had cropped up in response to the army’s abuses against civilians.

In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Buay said he would not disavow those statements, and instead likened the rebels to ISIS or al-Qaeda. When asked if he would tone down his rhetoric to prevent inciting violence, he instead doubled down, and said fears of genocide were overblown.

"If they don't want to accept the rule of the government and they take up arms, then they have to be crushed," he said. "If we don't tell [citizens] that these people are terrorists, they might think they are legitimate groups. So we tell people, you have to accept the government."

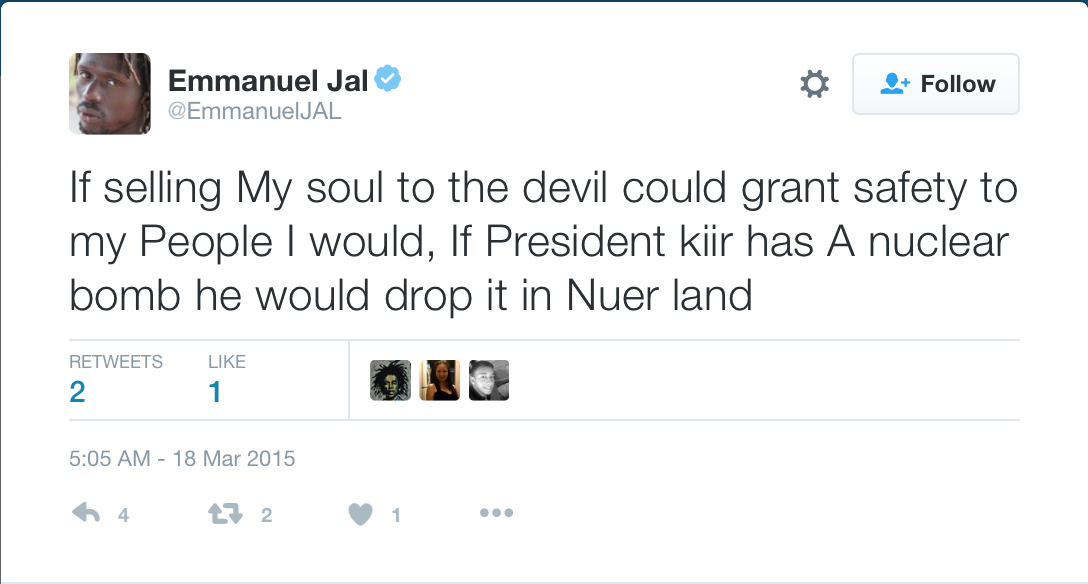

Even self-proclaimed “peace activists” have posted inflammatory statements, including South Sudanese-Canadian rapper Emmanuel Jal, who is also an adopted son of the late wife of rebel leader Machar.

When BuzzFeed News emailed Jal about the tweets, his management responded: “It isn’t a secret that South Sudan has the worst human rights abuse record in the world right now, with its government specifically targeting people based on their ethnic tribe.”

Researchers say diaspora influencers work together in well coordinated and funded campaigns to spread false news and vitriol, coalescing around a single message.

"You could imagine a scenario where somebody working on this hate campaign may be sitting in North America and has a partner or a colleague in Australia or New Zealand, and are kind of working around the clock," Kovats said. "You can have a 24-hour, moving campaign."

Besides direct calls for violence, spreading fake or exaggerated news has become a central strategy to turn South Sudanese against each other. A common tactic is to post images and videos from other African conflicts — pictures of bodies from the Rwanda genocide, for instance — while claiming they depict the massacre of a particular South Sudanese tribe.

In some cases, the images are stamped with logos of known international news organizations — their creators are especially fond of the Associated Press’s distinctive logo — in an attempt to lend legitimacy.

"Hoax messaging, fear propaganda — that's a really simple way of creating hysteria and fear by people who just don't know how to interpret these kinds of images and where they come from," said Kovats of #DefyHateNow.

And just as fake news in the US has been shared by President-elect Donald Trump and some of his close associates, these apparent hoaxes have reached the upper echelons of South Sudan's government and rebel groups.

The UN experts panel said in their November report that a senior government military officer showed them an unverified cell phone video as proof that rebels committed an atrocity. Machar's spokesman James Gatdet likewise once claimed on Facebook that Kiir's guards tried to arrest the rebel leader, sparking condemnation from the South Sudanese government, which forced him to take down the post.

Some South Sudanese websites appear to deliberately blur the line between real and fake news. One anti-government Facebook group, MirayaFM, shares its name with the UN's official radio station in South Sudan, Radio Miraya, which has led to confusion among readers who can’t tell the difference between them.

Meanwhile, Equatorian extremist website africanspress.org reposts stories from legitimate news sources, but repurposed with inflammatory headlines. One recent headline accused Dinkas of killing Equatorians for fun and turning them into meat — it was posted above an Agence France Presse (AFP) video about the UN's genocide warning. The AFP video is currently blocked from being played on the website.

One of the biggest fake news campaigns in South Sudan took place in mid-July 2016 to mobilize support against a proposed UN force meant to deploy in Juba, the capital.

The UN’s proposed 4,000-troop force was meant to secure the city after government troops forced the rebels out of the capital last July. The fighting killed hundreds and over 100 women were raped, including aid workers attacked by government troops in the Terrain hotel, where Americans were singled out for abuse.

The government strongly opposed the deployment, and pro-government social media accounts launched a massive effort online to spread false stories while aggressively targeting the UN, the US, and foreign journalists for abuse.

The first salvo, apparently launched accidentally, came from Ayuel Maluak Ayuel Atem, a journalist for the government-leaning National Courier who blogs as Chris Blakka and tweets as @ayes_chrises.

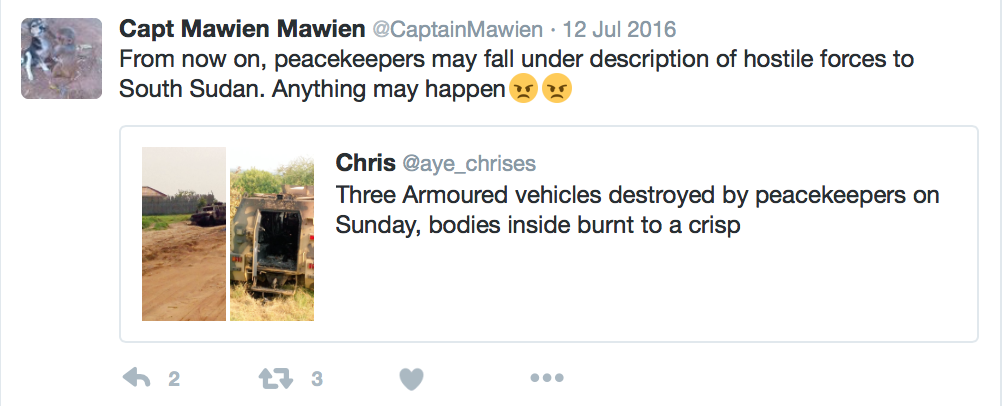

In a series of tweets and a blog post, Atem claimed the UN had killed South Sudanese troops by firing on armored vehicles and burning them alive inside.

Yet journalists who visited the scene found no evidence to back up the blogger's claim. Instead, it emerged that South Sudanese troops had fired on a separate UN armored vehicle, killing two soldiers from the Chinese peacekeeping force. The peacekeepers, rather than shooting back at the army, had fled their posts.

Atem told BuzzFeed News that he later received information that the UN did not fire on the soldiers, and changed some of his blog post accordingly.

But the damage was done and his tweets remain available for anyone to read. Influential pro-government Twitter accounts quickly spread Atem’s narrative, including two people who Bidal named as top influencers: @CaptainMawien, who would not identify himself to BuzzFeed News but denied being a propagandist, and @modernemeid, operated by Sieta “Sisi” Majok, an England-based former #DefyHateNow activist.

Days later, the Dawn, a Juba-based newspaper owned by government security operatives, which Majok told BuzzFeed News she has done some work for, published fake CIA documents purporting to reveal a US-backed plan to overthrow South Sudan's government. The documents alleged the US — often seen as aligned with the UN in South Sudan — was working in cahoots with military contractor DynCorp, whose staff lived in the Terrain compound which was attacked by government troops.

Two weeks after Atem’s original tweets, the National Courier cited South Sudan's ambassador to the UN, who alleged yet again that the UN killed government troops. South Sudan’s Mission to the UN did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ requests for comment.

With all of these stories circulating, prominent pro-government South Sudanese began directly inciting violence against the UN, including DC diplomat Buay and former BBC journalist Mading Ngor, who also has dual Canadian citizenship and lives in Juba. Both men were named by the UN experts panel as key pro-government "agitators" against the UN.

Buay and Ngor each denied that they were part of any network. They also said they were not inciting against the UN, but voicing legitimate political opinions.

But according to Bidal, the July anti-UN campaign was a clear example of a coordinated effort to incite against the UN. In the coming days, anti-UN street protests turned violent, with rocks thrown and journalists beaten. To date, the UN force has yet to deploy in Juba.

Groups like #DefyHateNow and #AnaTaban, an online artist collective, are trying to combat online hate by posting positive peace messages, directly challenging incitement, and urging people to collect screenshots of hate speech for future prosecutions.

The groups also hold workshops with South Sudanese youth to educate them on using social media responsibly.

Bidal said foreign governments must also intervene when diaspora incite violence from within their borders. "Though these guys are South Sudanese, they now have dual nationalities. I think it is supposed to be the government of those countries to hold them accountable," he said. "Let someone not sit in Australia or America and start preaching hatred."