Over the course of two months, a clandestine operation took place at Clark County Jail in Jeffersonville, Indiana. Unbeknownst to the inmates and to the guards, seven law-abiding citizens had volunteered to go undercover as jailed convicts in an attempt to help Sheriff Jamey Noel expose rampant drug use, crime, and corruption within the facility's walls.

This is the premise for 60 Days In, a gripping A&E docuseries that, since its debut in March, has become TV's No. 1 new unscripted cable series and the network's No. 1 program. The show — brainchild of executive producer Greg Henry and Noel, who runs Clark County Jail — offers not only an unprecedented viewing experience, but a fascinating examination of how and why prison changes people.

But pulling this series off was no easy feat. In addition to finding seven volunteers willing to exit their regularly scheduled lives and dwell among murderers, these select inmates were charged with investigating the jail while also attempting to keep their identities a secret. Producers also needed to consult an army of lawyers about the legality of this endeavor, cover the prison in cameras and microphones, invent a plausible cover story for their documentary crew, and ensure they could keep the participants safe, sane, and focused on the mission.

Despite two participants quitting during production — one for incredibly dubious reasons — the production succeeded with the task at hand for the most part. During the May 19 season finale, Noel said that the initiative had provided him with invaluable information about the prison's weaknesses and the nefarious ways prisoners exploited them.

"I'm surprised that it worked, but whether it's through luck or hard work, we made sure it would work," Henry told BuzzFeed News during a phone interview. "It's probably the first show I've ever made that I ... felt in my bones should be watched. We're really proud we pulled it off."

Over the course of an hourlong conversation, Henry explained how 60 Days In was executed, the unplanned moments that shocked him, what he really thinks of the participants who quit, and more lingering questions 60 Days In fans are dying to know.

1. What inspired the docuseries?

Greg Henry had a long-standing interest in producing shows that offer a unique look inside the U.S. prison system. He worked on Behind Bars: Rookie Year, Hard Time, and the County Jail series, but an identical frustration resurfaced in every one of these experiences.

"Every time we make a series in a prison, we come away feeling like everybody that we spoke to sort of had an ulterior motive and we weren't getting a true perspective on what it was like to do time," he said. "We were getting it through the eyes of someone who had committed a crime and therefore they earned their way to where they were. Or, with correction officers, they always have their perspective on the world as well. We really wanted to figure out a show where the voices you heard would be you and me. They would be ordinary citizens... so we would get to see it from a truly unbiased perspective."

A&E jumped at the opportunity and Henry's team began meeting with sheriffs around the country to try and find a facility that would meet their herculean needs. Enter Noel. "I met Sheriff Noel in Indiana and told him, broadly, what we were thinking and he laughed — in a good way," Henry recalled. The sheriff was elected on the heels of a corrupt administration and was attempting reform, but "he could only see topically how the reforms were taking shape and he could never get an inmate to give him the straight truth because the rules of the game are: If you talk to the cops, you're a snitch. That was our starting point and together we talked about what he could do, what he wanted to do ... but also understanding that by doing it on television, he could potentially have a much larger impact than just a local one on his facility. We took his lead, but it became a true collaboration."

2. Is this actually legal?

Is it legal to actively place non-offenders behind bars if they haven't been charged or convicted of a crime in a court of law? Turns out, yes. The bigger legal quandary production faced involved the rights of the inmates already in the jail.

"The first hurdles were just looking at the constitutionality of 24/7 [cameras] in a facility," said Henry. "We assembled some of the constitutional lawyers through our law firm, we had hours upon hours — which equals very expensive — conversations where we were going through every point. Every camera placement that we had, you would balance 'This would be the best camera angle' against 'This is what the Constitution allows us.'"

This is why you never see into bathroom areas or showers. "Those are zones that are completely protected and we'd never want to violate that privacy," Henry said. In addition to the 16 fully robotic cameras and 64 microphones, Henry and his team filmed inside the cells and conducted one-on-one interviews with the inmates under the guise of producing a documentary about first-time offenders, a description that conveniently applied to every 60 Days In inmate.

From the guards to those jailed, anybody who was shown on camera also signed a release agreeing to be filmed. The ones who didn't want to participate were simply moved to another housing pod. "We had around 300 inmates who were willing to participate." As for the bait-and-switch about the doc's intent, Henry said, "We're not coming out and deceiving anyone; we're just telling them the doc is about first-timers and that's the place we landed where everyone felt comfortable."

3. Where did you find the participants?

Henry's team got an early taste of how unpredictable this filming experience would be during the casting process. "One of the most surprising things was how many folks were willing to put aside their lives for two months to participate in a program like this," he said.

Henry estimates that they met with more than 300 people to try and find seven who satisfied the endeavor's needs. "It was a massive, mostly unconventional effort," said Henry, who culled candidates in part from online support and chat groups for victims, offenders, and law enforcement. Then all the participants were put through rigorous background and medical checks. "You can't put somebody behind bars who has a chronic medical problem because they're in there under an assumed name and there's no way to get them medication." Then began the process of identifying the ideal participant archetypes. "The sheriff knew going in that if he had seven [versions of the same person], he was not going to get a full perspective on what was happening inside from every possible angle."

So Henry and his team offered Noel, who had final say on all subjects, a rich list of the best candidates from which to pick. "It's months upon months of work to get it to the place we got it to ... but probably the most rigorous you will find in any television show."

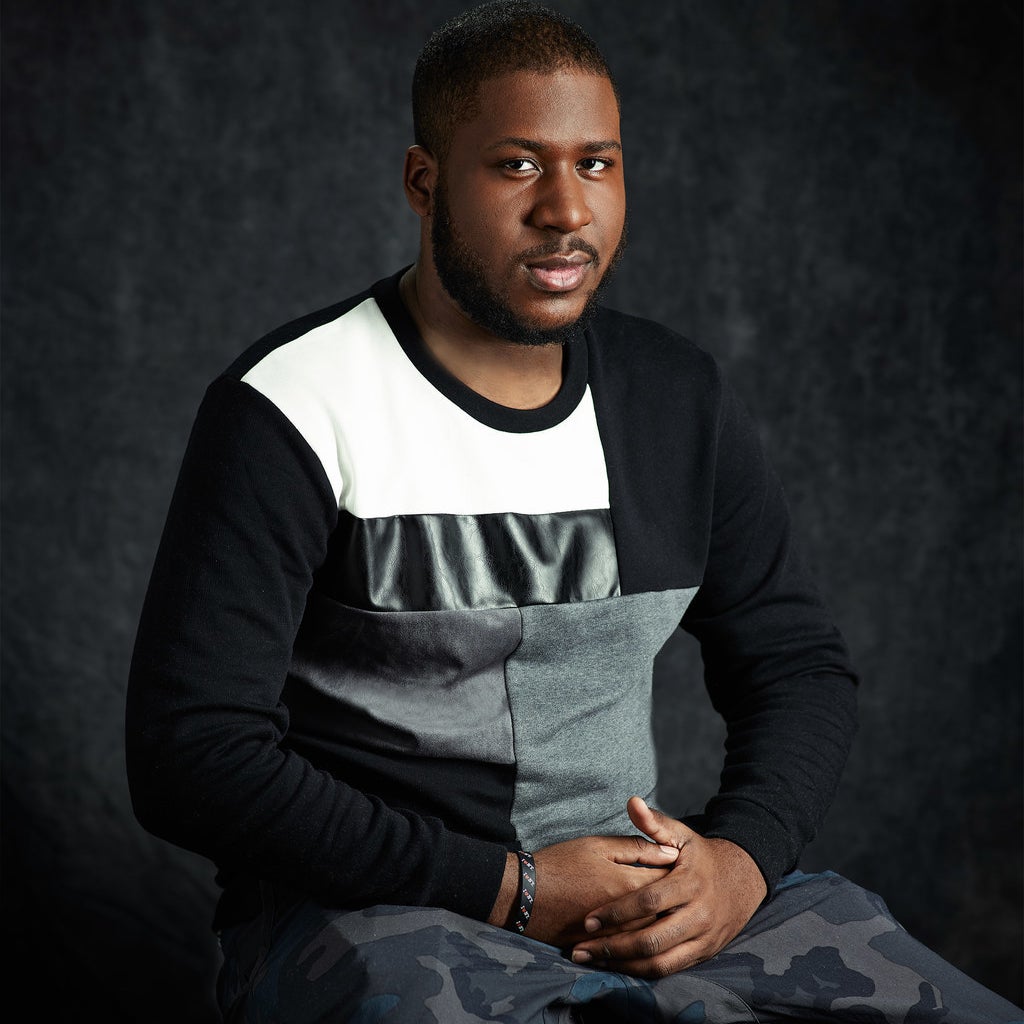

In the end, the seven people chosen for the program were Barbra, a stay-at-home mom; Isaiah, a 19-year-old whose brother was a convict; Jeff, a security guard; Maryum, a social worker (and Muhammad Ali's daughter); Robert, a teacher; Tami, a law enforcement officer; and Zac, an ex-Marine.

4. Do you regret casting Robert?

From the very beginning there was something off about Robert. And it wasn't simply that he asked irrelevant and odd questions during the participants' life-or-death training seminar before entering the jail. His entire attitude toward the project never seemed on the up-and-up — suspicions that were validated when Robert stepped foot inside his cell and promptly disregarded everything the professionals told him to do and not to do.

"Robert was very touch-and-go, very minute to minute because he went in and kind of did his own thing," Henry said. "For Robert, we were confident that a teacher's perspective might bring something, but things were different once that slammer door closed. The sheriff is very clear about his disappointment in the [reunion] show on the tactic Robert took."

About halfway through his time on the show, Robert became a target for the other inmates as they easily saw through the "facts" in his cover story. Sensing he might be in danger, Robert placed a towel over one of the cameras, a major inmate infraction, earning him a month in solitary confinement. While this meant he was no longer able to offer the program or the sheriff any valuable information, Robert was in heaven: He no longer needed to worry about his safety and was able to do nothing but read, one of his most cherished pastimes. It was a slap in the face to the entire operation and an utter waste of the opportunity.

Unfortunately production simply couldn't pull Robert out of the unit. "If he did not get the same treatment that any other inmate would get, it would raise questions among the staff and it would also get to the inmates because he had certainly made enough noise that people knew who he was," Henry explained. "So when he gets a 30-day commitment to segregation, at that point, if he wants to tap out, he can tap out. ... This is the part of the show where there are rules, there regulations, and they have to be followed, if anybody appears to be receiving favoritism, or if somebody has doubts, it raises questions. That speaks to the authenticity of this whole program."

In the end, as his time in solitary was wrapping up, Robert complained of a debilitating stomach ache and asked to be released from the program so he could see a doctor. The doctor couldn't find anything medically wrong with him, which was a relatively predictable diagnosis given that Robert previously wrote Sheriff Noel a secret note right before he fell ill asking not to be put back into general population.

5. Were you surprised by how successful Zac was?

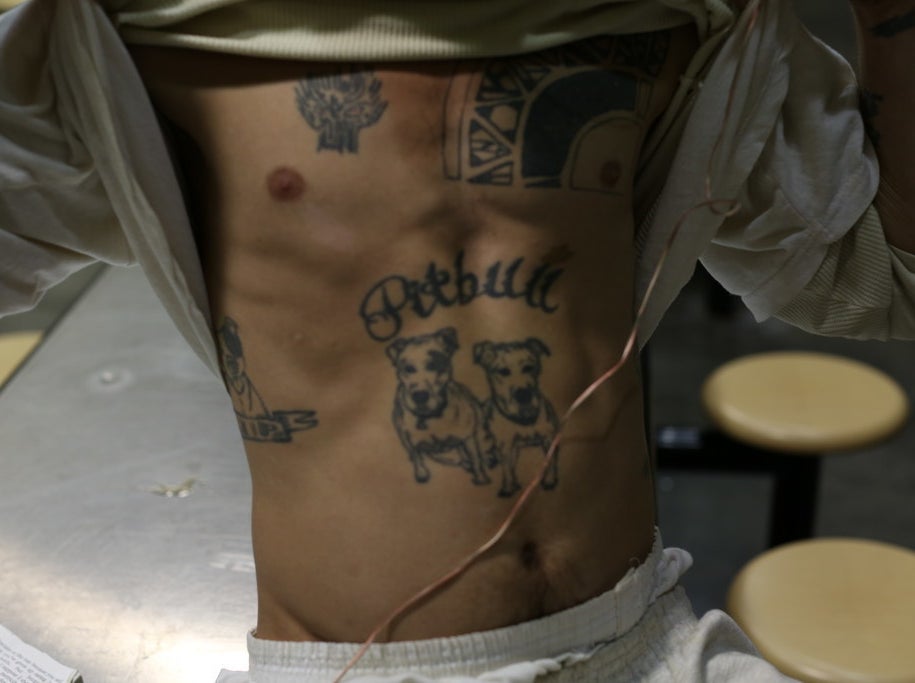

In terms of being a watchable character and an insider Sheriff Noel relied upon to uncover new information, no 60 Days In participant was more effective than Zac. His military experience allowed him to seamlessly integrate into two separate prisoner groups, a social maneuver that resulted in authorities uncovering deadly weapons and other contraband the prisoners were hiding.

"If you were to say, 'We're going to only use one person and just have one point of view,' Zac was the closest to what the sheriff was trying to pull off," Henry said. "Now, that said, he wasn't always perfect. He screwed up royally when he called that guy a bitch."

The other big screwup happened in Episode 5 when Zac was called to stand before a judge. The demand shocked not only Zac but also production, as none of the seven participants were actually placed in jail by the court, so certainly none of them should have ever been asked to go into court.

The confusion stemmed from the fact that — unbeknownst to producers — there was another inmate named Zac Holland at the same prison, and the wrong one had been summoned. But if the show's Zac actually made it all the way to court and in front of a judge, the massive, million-dollar secret would be immediately blown, as Zac would have to properly identify himself in front of the very corrections officers he was deceiving.

"We spent weeks talking about every possible eventuality, about everything that could happen, and that was the one thing we did not talk about," Henry said. The ensuing chaos — freaked-out producers whisper-yelling into their microphones, camera crews sprinting down hallways — made for one of the series' most gripping installments.

"When our Zac's name was called to go to court, we couldn't step in and say, 'Whoa, whoa, whoa — cut, guys!' We just had to let it play out because, again, if our Zac Holland gets pulled out ... people would know something wasn't right," Henry said. "It was terrifying when Zac is getting handcuffed to walk through outside, but that also let [us] know that something pretty damn real is happening."

In the end, the officers themselves realized the mix-up before the mission was compromised.

6. How close did Tami actually come to blowing her identity?

Socially speaking, many of the participants flourished behind bars — Zac and Barbra proved to be particularly popular — but others majorly struggled to fit in, like Robert and Jeff (who was punched by another inmate, causing him to quit). While Tami falls into the latter grouping, she stuck it out for all 60 days, despite repeated conflicts and never truly finding her groove with the other inmates.

"I think Tami [had] the closest you get to what a true inmate experience is when you are stripped of everything you know of being normal and civil," Henry said of her struggles, which included an incident where she, at her wit's end, mimed hanging herself. Tami's raw mental and emotional state also resulted in a series of odd statements where she implied to guards and other inmates that she didn't belong behind bars and it would all make sense soon. "We certainly weren't happy to hear that," Henry said. "The inmate experience — having all freedom taken away from you and being put on a regimented schedule where you had no control — went against everything she ever did in law enforcement, everything she ever knew, and she started to lose herself in there."

While everyone was suspicious of Tami, who was the first woman to enter the jail, producers realized they couldn't pull her out at the pre-planned release time for fear of exposing the entire program. But, in the end, Henry also believes that Tami had "the most transformative ride of anybody."

"This is one of the most surprising things about this program: Nearly every person — we will hold aside one person — came out the other side fundamentally changed in their worldviews," he said. "They were all really impacted by this in a way that I've never seen in anything. When you make television, it always has an impact on people, but they came out the other side — and what's strange is I think they all came out for the better."

7. How did the guards react to learning the show's true intention?

Given the show's secretive nature, a second season was filmed in the jail before the first began to air. When the second group of volunteer inmates exited the program, it was then that Noel told his staff about the documentarians' true intentions over the previous four months.

And, according to Henry, very few were actually angry they'd been lied to.

"The reaction in the room at the moment was actually pride," he said. "Pride that they were the place this had happened [and] excitement over what was going to be learned. At first there was some concern that the sheriff did this as a 'gotcha!' — which was never the intention. Then they realized that this is a guy who cares enough about this facility and the way it runs to help us run it better."

And that goodwill has continued, now that the show is airing. "I was back at the facility five weeks ago and I was not getting mean stares. I was getting hellos and handshakes, and that for me is always the bar." That sentiment extends beyond the jail's walls and into the Jeffersonville community, which has embraced the show in a big way. "There has been a sense of 'Thank you for caring enough to do this.' Our biggest concern in all of this was how would it be received locally. A lot of people were very surprised when it first came out, but as the show has been airing, the local press has been really excited that it happened there. It's been really well-received on the whole, locally."

8. Was the show's timeline fudged?

One of the more prominent nonvolunteer inmates to be featured on the series was 20-year-old DiAundré, who befriended Robert when he first entered the cell. Since his release, DiAundré has criticized the show's editing, saying it's misleading and events are shown out of context and out of order.

"Timeline really mattered to us. We did our absolute best to stick to the timeline," Henry said when he considered the criticism. "When you get into [editing], things happen that are hard to explain in a way that people can make sense of. What we found is that editing, no matter what, is going to alter the absolute timeline."

Henry also recommends that critics take memory into account. "We ran into this with a lot of the participants as well — but when you take someone's experience 24/7 and begin to edit it, it's hard to remember how it all unfolded when you lived it," he said. "There are a couple of times where things are switched with [DiAundré], but it's also in the service of trying to make sense of what exactly was happening in real time and that's our biggest challenge. But over the totality of it, I would stand behind it and say this is all truthful to what the experience was as we saw it in the time we were there.

"From the outset, we really, really counseled everybody on the team that we don't have control here. What we have control over is capturing and making sure we really hear and see everything. But what is going to happen, we just have to react to."

9. What has changed at the Clark County jail as a result of this program?

After every volunteer participant finished the program, each sat down with Noel and Capt. Scottie Maples for a debrief about what they learned during their time inside. Yes, as viewers saw in the finale, Zac's intel led to immediate raids and the discovery of contraband. But the influence of those 60 days on the jail hasn't stopped there.

"Maryum had some of the most valuable information for the sheriff," Henry said. "She said, 'You've got Alcoholics Anonymous but 85% of those girls are users and all they are doing in your jail is detoxing — there are no programs tailored specifically to addicts of narcotics, so you need NA there.'"

Every released inmate is also now given a card that contains phone numbers for crisis and help hotlines. "What we saw is that people who had committed no crime, people who had never been incarcerated before, walked out of that facility and they had trouble sleeping, they had trouble setting a schedule for themselves. And if you don't have a support system, are an addict, or have been in the system for a long time, those challenges are magnified a hundredfold," Henry continued. "The sheriff is so engaged and as long as he's in office, he'll continue to work on this. The fact that the show continues to air and he keeps getting press, that is the thing that makes sure he can effect real change. I know even behind the scenes things are changing, [and] I think this is just the start."