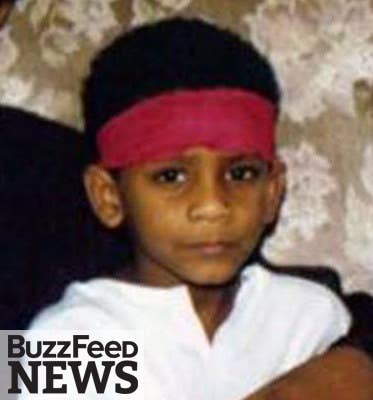

When El Shafee Elsheikh was a little boy, after his father had left, his mother would find him at the workbench by the summerhouse at the bottom of the garden in White City, west London, tinkering endlessly with engine motors, bicycle parts, and old computers. Elsheikh was slight and elfin-featured, with wide almond eyes and pointed ears under a cloud of dark curls. He cut a sombre figure, intently turning the parts over in his small hands, finding out what made things work, how to fix them when they got broken. On warm nights, his mother says, he liked to sleep alone down here, in the makeshift old wooden summerhouse with a sheet drawn over the door.

Years later, in 2011, when Elsheikh had grown into a striking young man in his early twenties, his mother found him here skulking with his CD player, listening to a torrent of hate. The words streaming out of his headphones, when she snatched them from him, were those of the notorious al-Qaeda-affiliated west London preacher Hani al-Sibai. By now Elsheikh had qualified as a mechanical engineer and was earning his living fixing cars and fairground rides. He was quiet, studious, and devoted to his family, and he made his mother proud. But on that day in the garden, she says, she feared for the first time that she was losing him to an ideology she did not understand.

"My kids were perfect. And one day it suddenly happened."

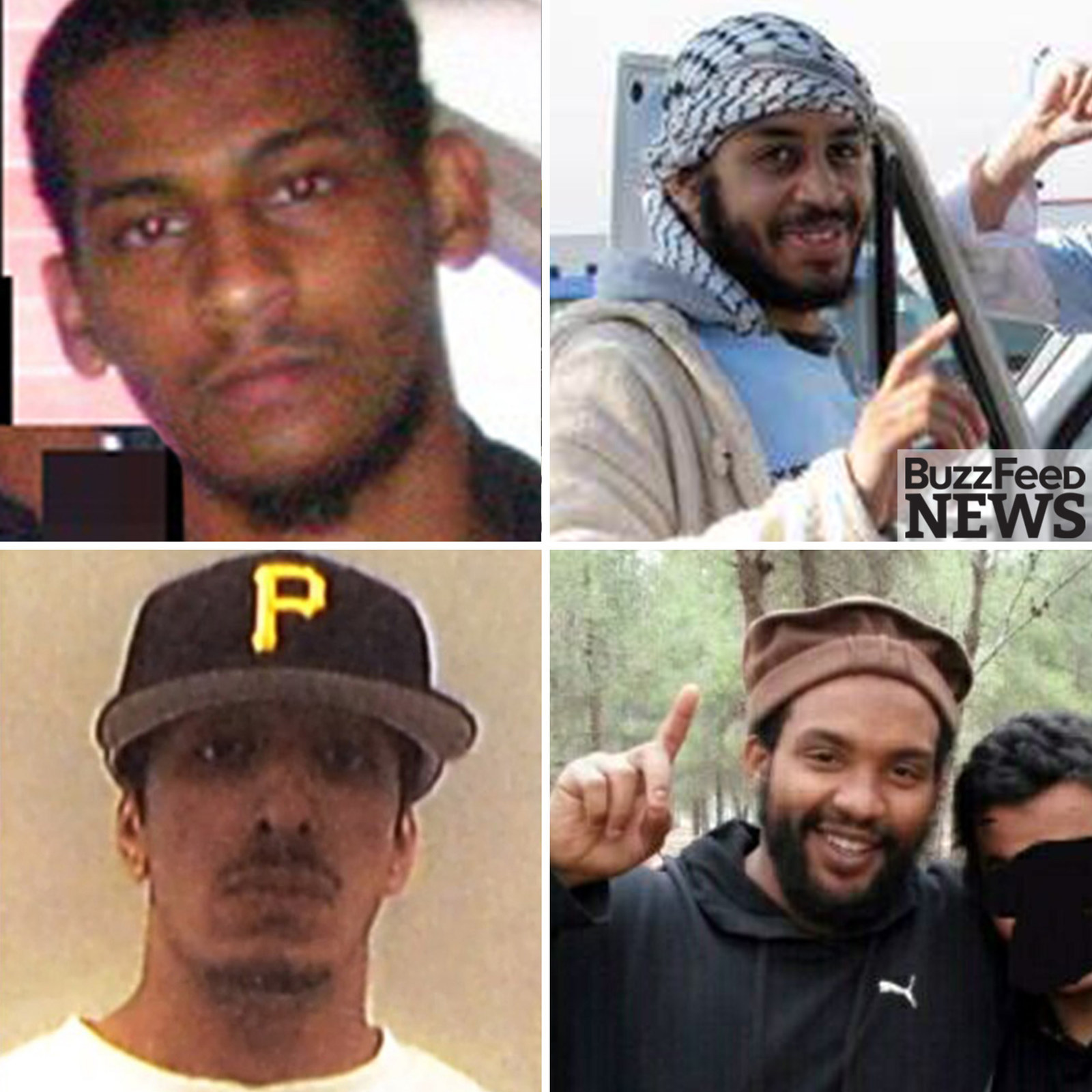

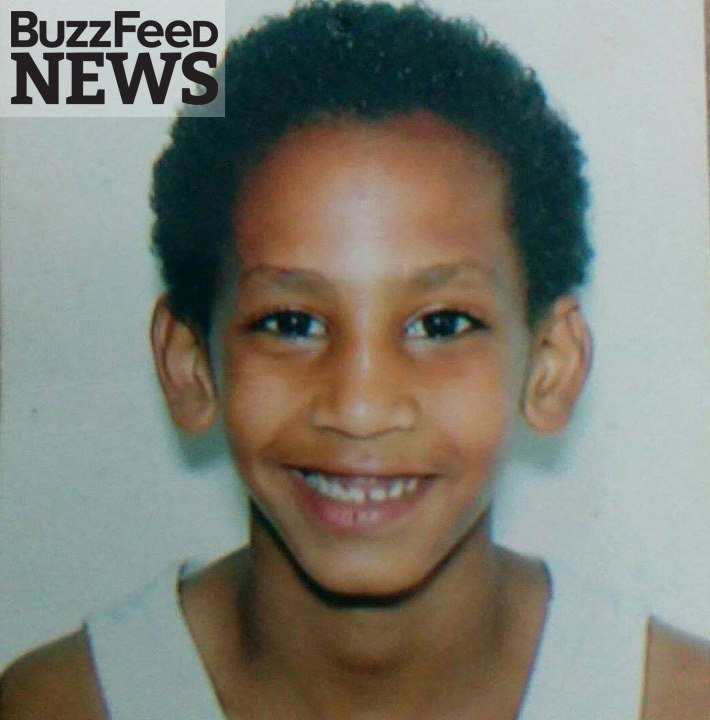

Now, five years on, Maha Elgizouli stands down here by the summerhouse, struggling to conceive of how the son she still calls her “little one” turned into one of the world’s most wanted terrorists. Elsheikh has just been identified by BuzzFeed News and the Washington Post as a member of the notorious ISIS execution cell of four British guards known as the “Beatles” and responsible for beheading 27 hostages and torturing captives with electric shocks, waterboarding, and mock executions. He is the fourth and final member of the terror cell to be named, following the unmasking of the group’s knife-wielding executioner “Jihadi John” as Mohammed Emwazi, and the two other guards as fellow west Londoners Alexanda Kotey and Aine Davis.

Now Elsheikh’s mother is speaking publicly for the first time since he ran away to wage jihad in the spring of 2012 after undergoing what she says was a lightning-fast conversion to radical Islamism. Soon after he fled, his teenage brother travelled to join him, and last year Elgizouli heard that her youngest had been killed fighting for ISIS in Iraq. “My kids were perfect,” she says now, with a look of blind incomprehension. “And one day it suddenly happened.”

Elgizouli’s disbelief at her sons’ sudden transformation echoes the experience of hundreds of families across Britain who have lost their children to ISIS. More than 800 British citizens have travelled to Syria and Iraq to wage jihad in recent years. All four members of the “Beatles” were ordinary young men from the same pocket of west London where Elsheikh was raised, and were radicalised in its mosques. Mohammed Emwazi was remembered by his schoolmates as a “nice guy” who loved football and S Club 7 before he found extremist Islamism and became “Jihadi John”. Friends of his fellow guard Alexanda Kotey said he was “quiet and humble”, an avid Queens Park Rangers fan who considered himself “as British as they come” before his conversion. Elsheikh, his mother says, was “very, very clever”, quiet and kind-hearted, a “very nice boy”. At the heart of her story is the same question being asked time and again in communities across the country that are struggling to get to grips with the spread of extremism: What makes these studious, unassuming young men susceptible to an ideology that so swiftly turns them into killers?

Elgizouli has invited us into her garden, and her lost boys are everywhere. Elsheikh’s workstation is just as he left it, with a few tools, nuts, and bolts scattered around. There is the tree he planted here as a child; and across the lawn is his young brother Mahmoud’s. On the grass is a tower of tyres Elsheikh collected, painted in green, red, and blue. And in the summerhouse, she points out a closed-up hot tub where the brothers used to play and the bed where Elsheikh slept out here when it was warm.

Elgizouli is small and delicate, swamped in an oversized grey wool jumper over a long dark skirt, and she gives the impression of having sunk somewhere deep inside herself. When she talks about her boys she often becomes temporarily reanimated, lighting up as she lists their youthful accomplishments, before catching herself and tailing off, remembering. Slowly, over the course of a 90-minute interview back inside the house, surrounded by framed pictures of her sons, she settles into a big cream armchair and tells her story.

The family have lived in White City since they fled the civil war in Sudan in 1993. Elsheikh’s parents were communists and liberal Muslims, described as “progressive” by their friends. His father left his wife and three sons a couple of years later and the children took the breakup hard. It was a struggle raising three boys as a single mother, Elgizouli says. But she worked hard to give them “everything they needed”. “I like my kids to do anything in their home,” she says. “I like to see the boys come here with their friends.”

Elsheikh was close to his younger brother, Mahmoud, and the family's eldest, Khalid, but he also spent hours alone at his workstation in the garden. Once, when Elgizouli's computer broke, she says he sat up all night fixing it for her. “He is a hard worker,” she says, with a flush of obvious pride. “I love him very much. He is very nice boy.” When she talks about her love for him she sometimes has to look upwards, trying to stop the tears falling beneath her brown-rimmed glasses. Her hands grip the arms of the chair and she takes a deep breath before continuing to talk.

Elsheikh’s fascination with mechanics persisted into his teens and when he left school he went to Acton College to study engineering. After graduating, he got a job in a local car garage, and on the side, “he would work on the machines in Shepherd’s Bush Green,” his mother says. “You know, the big funfair.”

“I love him very much. He is very nice boy.”

He was so diligent and responsible in her eyes then that she put him in charge of managing the whole family’s finances. “He was looking after me very well, my little one,” she says.

Elgizouli worked hard to shield her boys from trouble on the edgy streets of west London, where extremes of wealth and poverty can spread tension and disunity, but the eldest, Khalid, started running with a tough crowd. Then, in 2008, at the age of 19, Elsheikh got involved in a fight and was viciously attacked with a knife. “Something happen for Shafee. He is caught somewhere, I don’t know where, fighting,” Elgizouli says. “A boy stabbed Shafee in his back, on the side, and here, and here, and here,” she says, gesturing all over her torso.

Khalid later tracked down the attacker and fought him, she says, getting part of his ear bitten off in the struggle. That fight triggered a series of skirmishes between rival gang members in west London, culminating when a 15-year-old friend of Khalid's organised the murder of the young man who bit him. The teenage gunman was found guilty of murder, and Khalid himself was sentenced to 10 years for possession of a firearm with intent to endanger life.

Khalid’s conviction had a profound effect on Elsheikh. Dr Saleh al Bander, a former Liberal Democrat councillor and Sudanese community leader who has known the family for 20 years, described him as a “very kind, very reflective, and very patient” young man, who was “very upset that his older brother is spending years behind bars because he defended him”.

A close friend of Elgizouli’s who has lived with the family since 2008 said Khalid had been the leader of the family since the boys’ father had walked out on them, and his younger brothers were both deeply shaken when he was locked up. “The brothers loved each other very much, they were very close,” said the friend, who asked to be identified only as Blgiss. “When Khalid went to prison, both of them were lost.”

After that, Elsheikh became the de facto “man of the house”, and from then on, Blgiss says, Mahmoud did whatever he said. “He looked up to him very much."

At the same time as coming to terms with his brother’s crime, Elsheikh was falling in love. Aged 21, he told his mother he wanted to marry his childhood sweetheart, an Ethiopian girl he had met in Canada while visiting an aunt who lived near Toronto. Elgizouli was delighted. “I said this is a nice relationship,” she says. “I think my son is going to be happy, alive." She hoped the couple would "grow together”. They were married in Canada a year later, in 2010, in a six-day celebration with traditional Sudanese outfits.

"I said, ‘Never in your life come into this home and talk about jihad.'"

Elsheikh had promised to bring his bride home to Britain, and was bitterly disappointed when she was prevented from entering the country by UK immigration rules. A year after the wedding, he was back in White City without her, angry at the system and working his job at the car garage again. It was then he began to be influenced by other young men in the area who were immersing themselves in an increasingly radical strain of Islam.

Elgizouli says her son became friends with a young Eritrean man whose father was a vocal Islamist, and she overheard him advocating jihad while visiting her home. “I came straight to him and said, ‘Never in your life come into this home and talk about jihad.' Me, I teach my kids about religion, not you. Don’t give them any information about anything.”

The young man apologised, she recalls, but it was just a few days later that she found her son with his friend listening to radical Islamist teachings down by the summerhouse. “I found him with him there in the back garden listening to a CD and I could tell something was happening, because when I go to him, he pulls out the headphones and hides,” she says. “I said, ‘Shafee, give me that one, I need to see him.’ He passes me the CD and it is a man who working in a mosque in the high road.”

The CD contained sermons recorded by Hani al-Sibai, a notorious west London preacher on the UN’s al-Qaeda sanctions list, who had previously described the London 7/7 bombings as a “great victory”. He had also been convicted in absentia of terrorism-related offences in Egypt, including recruiting for al-Qaeda. Sibai has since been implicated in the radicalisation of Mohammed Emwazi, who fronted the on-camera beheadings of 27 hostages being held captive by the “Beatles”.

Elgizouli was afraid. On the CD, she heard Sibai encourage his followers to ignore their parents if they tried to get in the way of the holy mission to fight jihad, because “Allah is more important than them”. She says: “I talked to Shafee and said, ‘Shafee, you want to go and be a dead Muslim?’ He said, ‘No, Mummy, just he asked me to listen.”

"I said, ‘Shafee, you want to go and be a dead Muslim?’ He said, ‘No, Mummy.'"

But soon after that, she learned her son had begun attending three mosques in the area and listening to sermons by Sibai. And then, she says, clicking her fingers quickly in the air, his radicalisation was “like that”.

Bander, too, said Elsheikh’s transformation was astonishingly quick from that point onwards. “I am still trying to understand how this very soft-spoken, very kind kid suddenly transformed within a very short period to join ISIS,” he said. “It was weeks, believe me, it was so fast.”

“It amazes me because his parents are committed communists who fled a brutal regime in Sudan and he comes from a very progressive family,” he said. “So after all these very open and progressive surroundings, he’s found this very radical ideology.”

Soon Elsheikh was dressing in long black robes, had grown a beard, and was spending his days distributing Islamist literature and perfumes outside Shepherd’s Bush Market. So instantaneous and perplexing was his transformation, his mother says, that she began to believe he was being drugged. She wondered if recruiters were spiking the “Arabic perfume” they gave to their followers, and it was “going through their skin into brain”. She also puzzled over whether his food or drink had been laced with some mind-altering substance. One thing she was sure of: “I know what’s going on in Syria: This is not Islam, not at all. Islam is different than that, politically they are using Islam.” She couldn’t understand why her son had fallen for it. “Shafee is a very, very clever boy. Never anybody can cheat him, never. I know my son very well.”

Elgizouli’s friend Blgiss, who was living with the family at the time of Elsheikh’s conversion and is with her for some of the interview, recalls her unease as she watched him turning against his mother after attending the sermons. “They controlled their prayers,” she says. “Shafee would come back arguing for hours with his mother’s interpretation of Islam. He never used to argue with her like that. He was very respectful.

“One day I remember, he came up to you,” she says, advancing towards Elgizouli in her armchair, pointing a finger right up to her nose, “and said, ‘You know, Allah says your mum can be your enemy.’” She steps back. “They washed his brain,” she says.

"I am a single mother. I can’t go to the mosque with them. I need to go inside to see what the imam say to my son.”

One of the last conversations Elgizouli had with her son face to face served to intensify her fears about the path he had embarked upon. She had recently met a friend of his from the mosque, a young Syrian man in robes with a shaven head and a long beard, and had taken a dislike to him. Two months later, she says, “I found Shafee crying.” She asked him what had happened and he drew closer to her. He said: “You know the boy you don’t like, Mum? He died, he passed away.”

"Where?" she asked.

“In Syria.”

Despite this shock, Elsheikh was encouraging his younger brother, Mahmoud, to come to the mosque with him. As a single mother, Elgizouli was unable to go inside with them to hear the preaching for herself or try to challenge what was being taught. She began to see the same signs of early radicalisation in the teenage Mahmoud that she had witnessed only months before in his older brother.

At her wits’ end, Elgizouli travelled to Sudan to visit her family. She wanted advice about how to handle her two boys back home. “I have a big family in Sudan, all is communist,” she says. “They have a good brain.” It felt good to be among her own people, but the night before she was due to fly back to London, she talked to Elsheikh on Skype and became worried about his whereabouts. “I say, 'I need to see my home, see you at home,'” she says. He managed to evade the request, but she told him: “Put some petrol in the car, you have to be in the airport because my flight and everything.” She says he replied: “OK, Mummy, bye bye.”

When she walked through the arrivals gate at the airport searching for her son’s face in the crowd, she felt the panic building inside her. “I am looking out for Shafee, I find Mahmoud only,” she says. “When I looked at him, something hurt me here,” she goes on, pointing to her heart, “because he’s wearing that Islamic robe. I said, ‘What is this, Mahmoud?’ He said, ‘Now I am a Muslim.’”

Mahmoud, then 17, was tight-lipped about the whereabouts of his brother, but then their neighbour gave Elgizouli the dreaded news that she had seen him getting into a taxi with a travel bag days before. It was April 2012, and her worst nightmare had come true. Her son had run away to Syria to wage jihad.

Elgizouli was distraught, and terrified that she was losing Mahmoud too. “I called my husband in Sudan, told him, ‘I want to bring Mahmoud to Sudan, I am scared here,’” she says. “I ask him many times, 'I need you to help me because I am a single mother.' I told him, 'I need help, I can’t go to the mosque with them. If I go with a man I can’t enter. I need to go inside, I need to see what the imam say to my son. Please help me.'”

She succeeded in persuading Mahmoud to travel back to Sudan with her for a holiday, but once they arrived her fears grew. “After two, three weeks, I worry because he is talking: ‘I need to go, I need to jihad.’”

"They told me, 'You have not got permission to take his passport because this is a British man, he is 17 now.'"

Determined to stop him, Elgizouli says she pocketed her son’s passport and took it to the British embassy in Sudan to speak to an official. “I told him everything about Shafee; he said to me, 'I know about your boy.' I said Mahmoud is a young son and I am scared he go, this why I take his passport with me. He said, ‘No, you have to give him his passport … you have not got permission to take his passport because this is a British man, he is 17 now.'”

Elgizouli says she told the official: “Listen, don’t tell me this is a British man – this is my son, before he is British, he is my son, he is from here, and if you refuse to help me protect him, I will protect him myself.” She confiscated the passport herself, but within a month Mahmoud told her he had been back to the embassy to say he had lost his passport and they had given him a new one. “Why?” she asked. “Why they do that?”

Then Mahmoud disappeared. For three weeks the family scoured the local hospitals and police stations looking for him, desperate to believe he hadn’t fled to join his brother. After 21 days, Elgizouli received the text message she had dreaded, from Elsheikh’s wife in Canada. She had spoken to her husband the previous day, it said, “and he told me Mahmoud arrived to him”.

The 17-year-old had procured funds for a ticket from a jihadi network in Sudan and flown to Turkey using his new passport. From there, he had crossed the border into Syria and found his brother. Elgizouli says Elsheikh was angry with his younger brother for following him out to the warzone, but Mahmoud was determined to fight alongside him.

Last year Elgizouli picked up a phone call from Khalid in prison and heard the words she had feared most. Mahmoud was dead. Elsheikh had called Khalid’s wife, who had called his brother, to inform the family that their youngest son had been killed fighting for ISIS in Iraq. When Elgizouli remembers the moment she heard this news, her tears fall freely. She takes the hands of our reporter in hers, first one then both, and she grips them tightly as the tears trickle down her cheeks. At some point, her fingernails were painted bright pink, but most of the varnish has worn off, and she is embarrassed by the clutter in her living room. “If you came before Mahmoud had died,” she says in sobs, “you see different person.”

“Mahmoud was the victim here,” her friend Blgiss says. “He was only radicalised because Shafee was.”

After learning that her youngest son had died, Elgizouli says she tracked down Sibai, the radical imam she blamed for sending her sons to Syria, and confronted him. “I slapped him in the face,” she says. “I said to him, ‘What have you done to my sons?’”

She lives entirely without her family now, with her eldest son behind bars, her youngest dead, and her middle child in the crosshairs of intelligence agencies on both sides of the Atlantic. She fills the house with friends as much as she can, which she says makes her feel less alone.

Through everything, Elsheikh has stayed in touch with his family. He took a second wife, a Syrian woman, who gave birth to a daughter two years ago, named Maha after his mother. A picture of the black-haired baby girl, round-eyed, pink-cheeked, and smiling, is on the screen of Elgizouli's phone and she shows it off with subdued pride. His Ethiopian wife also travelled from Canada to join him in Syria and, three months ago, bore him a son. The boy is named Mahmoud.

"I hope he changes his mind. I hear now many boys run away. I hope Shafee is one.”

When BuzzFeed News approached her, Elgizouli was unaware that her son had been identified as a member of the “Beatles”, though she knew he was working for ISIS. She wondered if the terror group just wanted him for his skills as a mechanic, and allowed herself to hope that one day the spell might break and he would come home.

“I hope,” she said, “he changes his mind. I hope so. I hear now many boys run away ... I hope Shafee is one.”

When she hears that intelligence agencies have identified her son as a member of the execution cell, she drops her head into her hands and rocks backwards in her chair, wailing. “No, no, not Shafee,” she cries, and her friend Blgiss comes running from the next room. She sobs uncontrollably, speaking in rapid Arabic interlaced with Shafee’s name, making cutting gestures across her throat. Blgiss grabs her around the shoulders and shouts: “You are his mother. He is a grown man. You did not do this.”

Later, when the sobs have lessened, she shakes her head and says: “That boy now is not my son. That is not the son I raised.”