One of Jeremy Corbyn's headline policies in last month's general election was the scrapping of tuition fees in England, which proved so popular one of Theresa May's most senior ministers has since called for a "national debate" on it.

Adding to the debate in England, Peter Scott, a professor of higher education studies at the Institute of Education, wrote an article for The Guardian saying the end of tuition fees was nigh and could come about at the next election.

North of the border, Scotland's first minister Nicola Sturgeon tweeted the article, welcoming the prospect of the "rest of the UK" – meaning England – "following Scotland" in abolishing tuition fees for university students.

Prediction that rUK will follow Scotland in abolishing tuition fees (NB author is our Widening Access Commissioner) https://t.co/UYWCzVZhpk

However, Sturgeon's policy is far from universally popular in Scotland, and has brought its own problems when it comes to making sure people from all backgrounds have fair access to university education.

BuzzFeed News has spoken to experts in university funding and brought together academic reports that explain why scrapping university tuition, while popular, might not be the answer to problems with higher education in England.

1. It doesn't actually help people from less well-off backgrounds get in to uni.

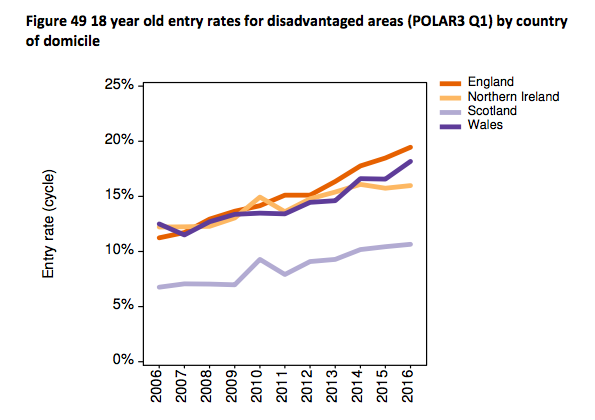

Scotland – the only place in the UK that has scrapped tuition fees for university students – actually has the worst record in the UK for getting people from poorer backgrounds into university, according to education charities.

The Sutton Trust concluded in a 2016 report that free tuition has no effect on getting more disadvantaged students into uni, and that Scotland's record for getting people from poorer backgrounds into uni is twice as bad as England's.

The report showed that, in Scotland, 18-year-olds from the most well-off areas of the country are four times more likely to go to university than those from the least advantaged areas, despite the lack of university fees.

In England, which does have a fees policy, students from the most advantaged areas are just over twice as likely to go to university as those from the least well-off areas, and three times as likely if they're from Northern Ireland or Wales.

"Free tuition hasn’t helped," education funding expert Lucy Hunter Blackburn told BuzzFeed News. "The proportion of people who go into university from poorer backgrounds at 18 is lower in Scotland than it is in the UK nations – that’s been the case for a long time and that continues to be true."

According to Hunter Blackburn, a small number of extra places were created by the Scottish government in 2013. This caused a rise in the number of disadvantaged students going to uni, but the policy was discontinued.

The report from the Sutton Trust concluded that while there were "clear positives" from the free tuition policy in Scotland – not least that it removed one type of debt from Scottish students – it had done nothing to make education more equal.

The report said: "The abolition of student tuition fees in 2000 and of the graduate endowment in 2007 did not lead to increased rates of university participation overall, or by students from less advantaged backgrounds."

2. It comes at the cost of other forms of student funding, like college places and nonrepayable student grants.

Scotland is funded largely from a predetermined "block grant" of money given to it by the Westminster government, which means each Scottish government department is then given a set budget to divide up as it sees fit.

With a block of money ring-fenced to pay for university tuition for Scottish students, the education budget has been brought under strain. The department, unable to borrow more money, appears to have sacrificed college places and nonrepayable bursaries in its place.

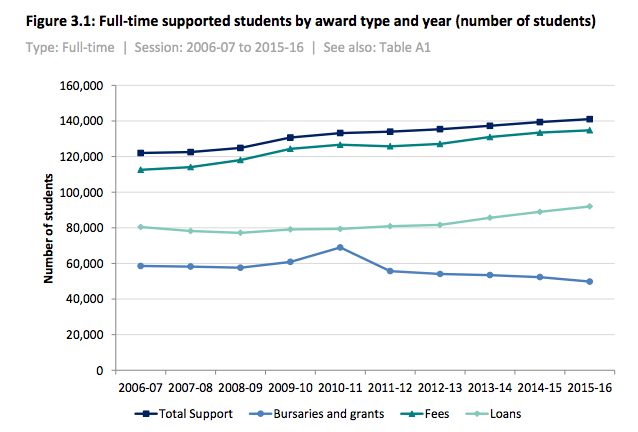

The most up-to-date figures from the Scottish government show that bursaries have been slashed, particularly from 2010 onwards, while Scottish students have become more and more reliant on loans they have to pay back.

The graph below shows that, while the cost of covering fees for Scottish students has increased year on year from 2006 onwards, the way students are supported is gradually shifting from grants to loans.

According to a 2016 report from Audit Scotland, between 2005-06 and 2014-15 there was a 53% reduction in real terms in the amount of bursaries and grants provided to Scottish students, and a 111% increase in student loans.

"Anyone who doesn’t think free tuition isn't a part of the picture there isn’t being realistic," said Hunter Blackburn. "Two big things happened; one was travel grants were abolished and the other is the big cut in means-tested grants."

She added: "We have ring-fenced spending on fees over the period since 2010, it’s been completely protected, and the budget for grants and bursaries hasn’t. That’s the choice the Scottish government made."

Additionally, Sturgeon's own poverty adviser has criticised a 10-year low in the number of Scottish students at colleges, saying the results showed university funding had received "greater protection from hard financial times".

3. You have to control the number of university places you're giving out to students much more tightly.

One major problem with free tuition is that the government is forced to cap the number of students who can take it. Even if demand for university places was to increase, therefore, it couldn't be matched with available places.

Academics have argued that the cap on student places has led to a halt in the growth of Scotland's universities, whereas in England, where a cap doesn't apply, it has allowed universities to expand with the demand for places.

The Sutton Trust report states that the best chance of getting students from poorer backgrounds into university is when universities are expanding, as "under such conditions they are not striving to displace middle class students".

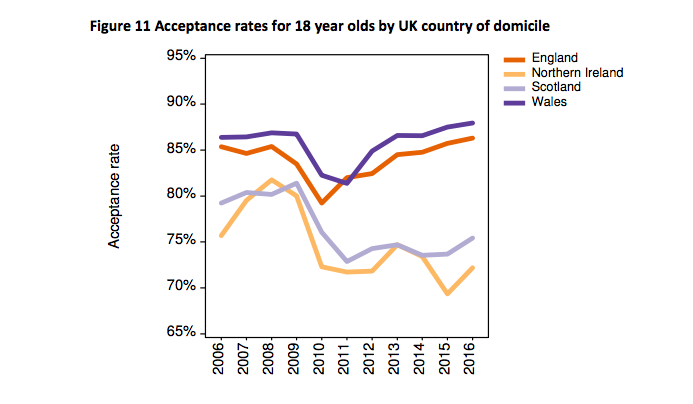

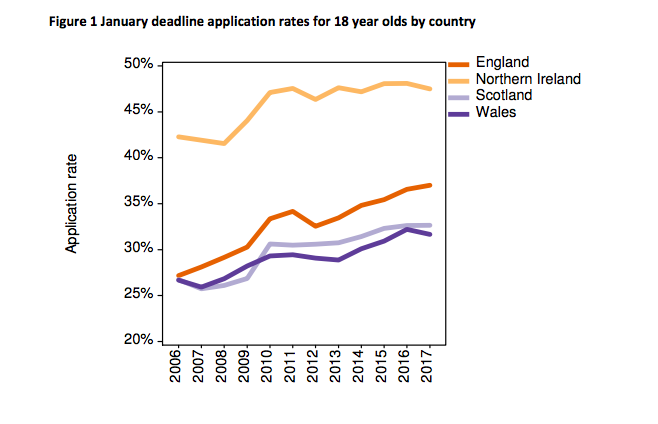

Partly because of the cap, as the two graphs below show, the acceptance rate in Scotland is around 10 percentage points lower than it is in England, despite applications for uni places steadily growing in both countries.

"When you fully fund fees you have to control the number of places more tightly," said Hunter Blackburn. "What you see happening is that since about 2010 the Scottish system hasn’t been able to grow in response to that rising demand.

"Demand is rising across all backgrounds and in England they can absorb that demand because they can afford to let their system grow and expand but here, where we're funding it all up front, we have to cap places.

"That’s led to an extraordinary dip in acceptance rates, which is worrying because it tells you we’re not able to respond to demand. We haven’t been able to increase the number of kids going in from all backgrounds, because there’s a cap."

Ultimately, the cap on student numbers in Scotland means there's fiercer competition for places than there is in England, which disadvantages nontraditional students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

4. It doesn't actually stop Scottish students racking up pretty hefty debts while they're at university anyway.

Because of free tuition, Scottish students tend to leave university with much less debt than their counterparts in England – but that doesn't mean they are left with no loans to pay back at all.

The average Scottish student leaves university with debt of £11,281. According to Audit Scotland, that figure is expected to increase to around £20,000 by 2019. However, this tends to place a heavier burden on poorer students.

The report states: "Scottish students from middle class backgrounds leave university with the least debt of any group in the UK, since they do not incur tuition fees if studying in Scotland and are likely to receive help with maintenance costs from their parents, thus avoiding maintenance loans."

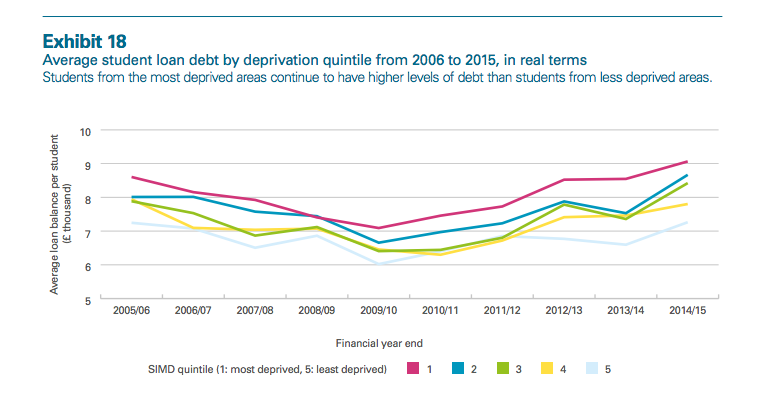

It is because of this, however, that students from poorer backgrounds in Scotland end up with the highest levels of debt, as the Scottish system often lacks the grants given to more disadvantaged students in the rest of the UK.

The Scottish government has pointed out, however, that student loan debt is lowest in Scotland – largely due to the potential £27,000 saving from not having to pay three years of university tuition.