British people are moving to the left in their views on tax, benefit claimants, public services, and a host of other issues, according to this year's findings from the British Social Attitudes survey, which picked up the shift in the months before Jeremy Corbyn's surprising performance at the general election.

The BSA survey, which has been conducted every year since 1983, is the UK's landmark study of the public's views on economic and social issues, including civil liberties. This year's findings, published on Wednesday, reveal a leftward shift on a range of issues, but also show the public holding a range of traditionally conservative views, especially on crime, terrorism, and immigration.

"For both the left and conservative sides of the political divide, you could feel quite positive reading this report, provided you ignored the other half of it," said Roger Harding, head of public attitudes at NatCen, the social research agency that conducted the survey.

The research shows the UK public strongly supporting social liberties – such as LGBT rights, sex before marriage, abortion rights and euthanasia – while expressing a deep scepticism of civil liberties, with a majority even saying they would support indefinite detention of terror suspects without trial.

The report also shows a country often divided on issues by age and education, particularly on Europe – underlining that Brexit will be a source of mounting tension in the next few years.

The research was carried out by staff conducting hour-long interviews in almost 3,000 homes between July and December 2016.

Tax more, spend more, redistribute more.

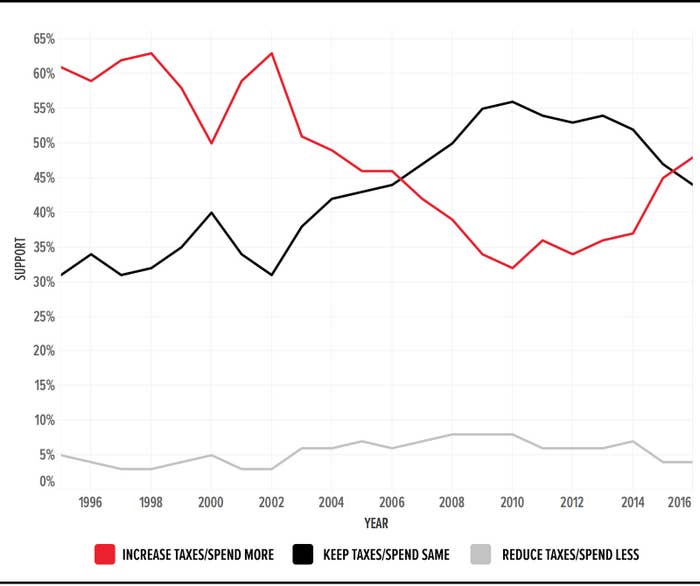

For the first time since the financial crash, which began in 2008, more members of the public wanted to increase taxes and spend more on public services than keep them at the same level they are now – signalling an end to public support for the era of austerity.

Should the government increase taxes and spend more on public services?

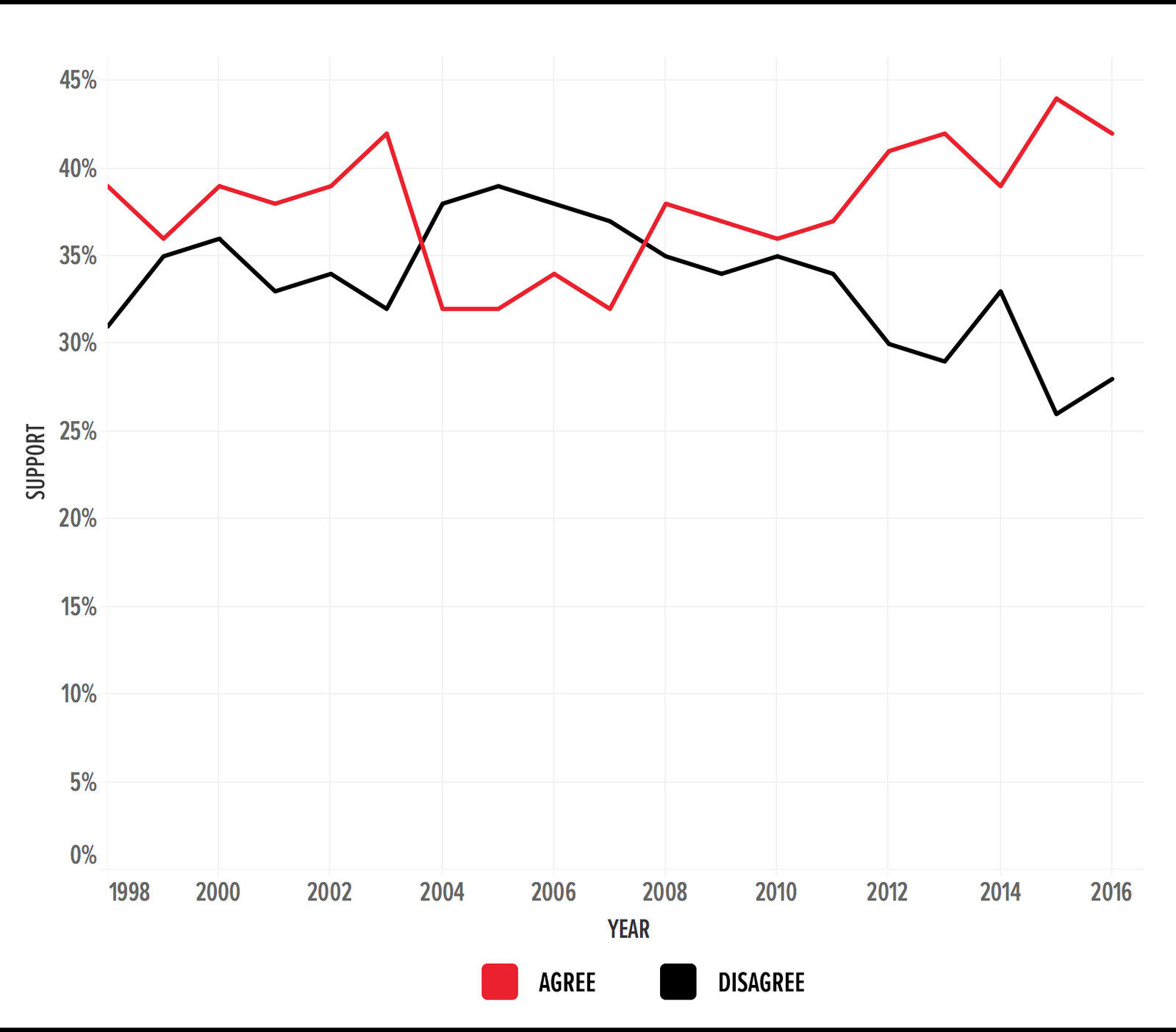

Participants also remained narrowly in favour of redistributing income from the rich to the poor, although at roughly similar levels to those since Conservative-led governments first took power in 2010.

Should the government redistribute income from the rich to the poor?

The research also showed views on benefits were changing, but only to an extent. The proportion of the UK population who believe people are "fiddling" unemployment benefit dropped from 35% as recently as 2014 to just 22% in the latest research, its lowest level in 30 years. But a higher portion of people said it was wrong to falsely claim £500 in benefits than said it was wrong to avoid £500 in tax by, for example, not declaring casual work.

Support for increasing unemployment benefits, however, remained at just 16%, half the level it was 20 years ago. The survey also showed slightly falling support for pensions – for the first time ever in the research's history, pensions were not the public's top priority if more money were to be spent on benefits, with disability benefits overtaking.

Harding sounded a note of caution for those on the left reading the results on taxation, spending, and the economy as a sign of things to come, however.

"This measure may now have had a tipping point," he said, "but it's not at all back to the heights these measures reached in the 1990s and even early 2000s, when the then Labour government were out making the case for this."

The country is getting more socially liberal – and this is accelerating.

One of the stories the British Social Attitudes survey has told since its launch in 1983 is the slow tale of the UK becoming ever more socially liberal.

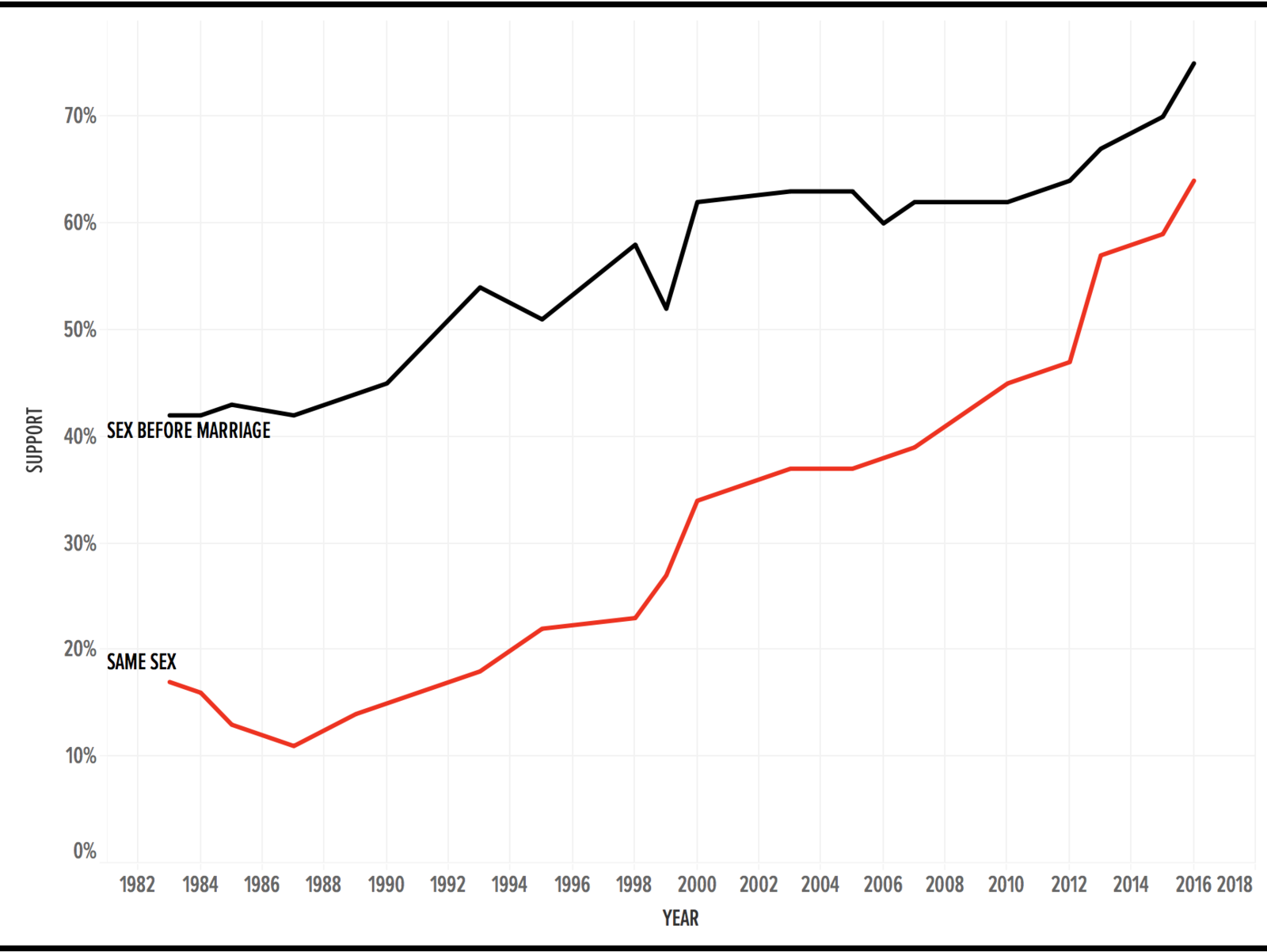

Nowhere is this more dramatic than on attitudes towards same-sex relationships, where the survey's phrasing has remained unchanged since it began. Participants are asked whether they believe sexual relations between adults of the same sex are always wrong, mostly wrong, sometimes wrong, rarely wrong, or not wrong at all.

In 1987, just 11% of UK adults said they believed same-sex relations were not wrong. Over the following 25 years, this figure rose slowly every time the question was asked, but was still just 47% in 2012 – but then, as same-sex marriage was legalised, leapt 10 points in a year. In this year's study, the figure jumped again by another five points, reaching 64%.

This shift is also reflected across wider society, with 55% of people identifying as Anglicans saying same-sex relations are not wrong at all – up from just 31% four years ago.

Similarly, support for sex before marriage reached another all-time high, up five points to 75% of the public saying it was not at all wrong – and while older people are still more likely to disapprove than their younger peers, this gap is closing: A decade ago the gap between oldest and youngest on this issue was 53 points. Now it's just 25.

Proportion of the public who say sex before marriage (black line) or same-sex relations (red line) are "not wrong at all".

The UK also remains broadly liberal on the issues of abortion and euthanasia. In 2016, 70% of UK adults said a woman should be allowed an abortion if she didn't want a child, while 65% said it should be allowed for couples who could not afford more children – both all-time highs in the survey results. Surprisingly, even UK Catholics broadly support abortion, with 61% backing it in the circumstances of an unwanted child, versus just 33% in 1985.

Euthanasia – a doctor or family member ending the life of a terminally or chronically ill person at their own request – is illegal in the UK, but the public strongly support it, with 77% saying a doctor should legally be able to end a life in these circumstances.

People have very tough views on law and order.

The fieldwork for the NatCen research was carried out in late 2016, before the terror attacks that hit London and Manchester in 2017, but even then the public showed strong support for greater action against terror suspects, and on law and order in general – suggesting the country's socially liberal views have not expanded into civil liberty concerns.

The public are willing to go much further than UK law allows to tackle terror. In the circumstances where a terror attack is expected – which could be reflected by the UK's current "severe" threat level – 70% think police should be able to stop and search people at random. At present, officers must have "reasonable grounds" to conduct a stop and search.

More drastically still, 53% of the UK public support indefinite detention without trial of terror suspects if attacks are deemed likely. UK law only allows detention for up to 14 days in such circumstances.

Elsewhere, 80% of the public support government video surveillance in public spaces, while 50% support email and internet surveillance.

"Our views on civil liberties haven't changed a lot, we just remain tough – to some even illiberal – on these issues," said Harding. "On detention without charge – which is basically internment – the limit now is 14 days. … That half the public support this on a more permanent basis is telling."

Support for increasing defence spending is also at a 30-year high, with 39% of the public backing it versus just 20% who would like to see it cut.

The public is sceptical of the EU and immigration – but with a big divide.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the research, which was carried out in the immediate aftermath of the UK's vote to leave the EU, showed increased Euroscepticism and a hardening of views on immigration.

The survey saw a large jump in support for leaving the EU, or reducing the EU's power if the UK did remain, at 76%, up from 65% just 12 months before. On immigration, 65% said the UK should require immigrants to speak English and have good qualifications and work skills.

The research asked how people voted in the EU referendum, and compared it to other long-running issues in the survey, finding that 73% of people who worried about immigration voted Leave versus just 36% who said immigration wasn't a concern.

Similarly, 72% of people holding views described by the researchers as "authoritarian" voted Leave, versus 21% of those with "libertarian" views – backing up claims that the vote was more about immigration than the pro-immigration, pro-free-trade free-market approach advanced by Brexiters such as Douglas Carswell or Dan Hannan.

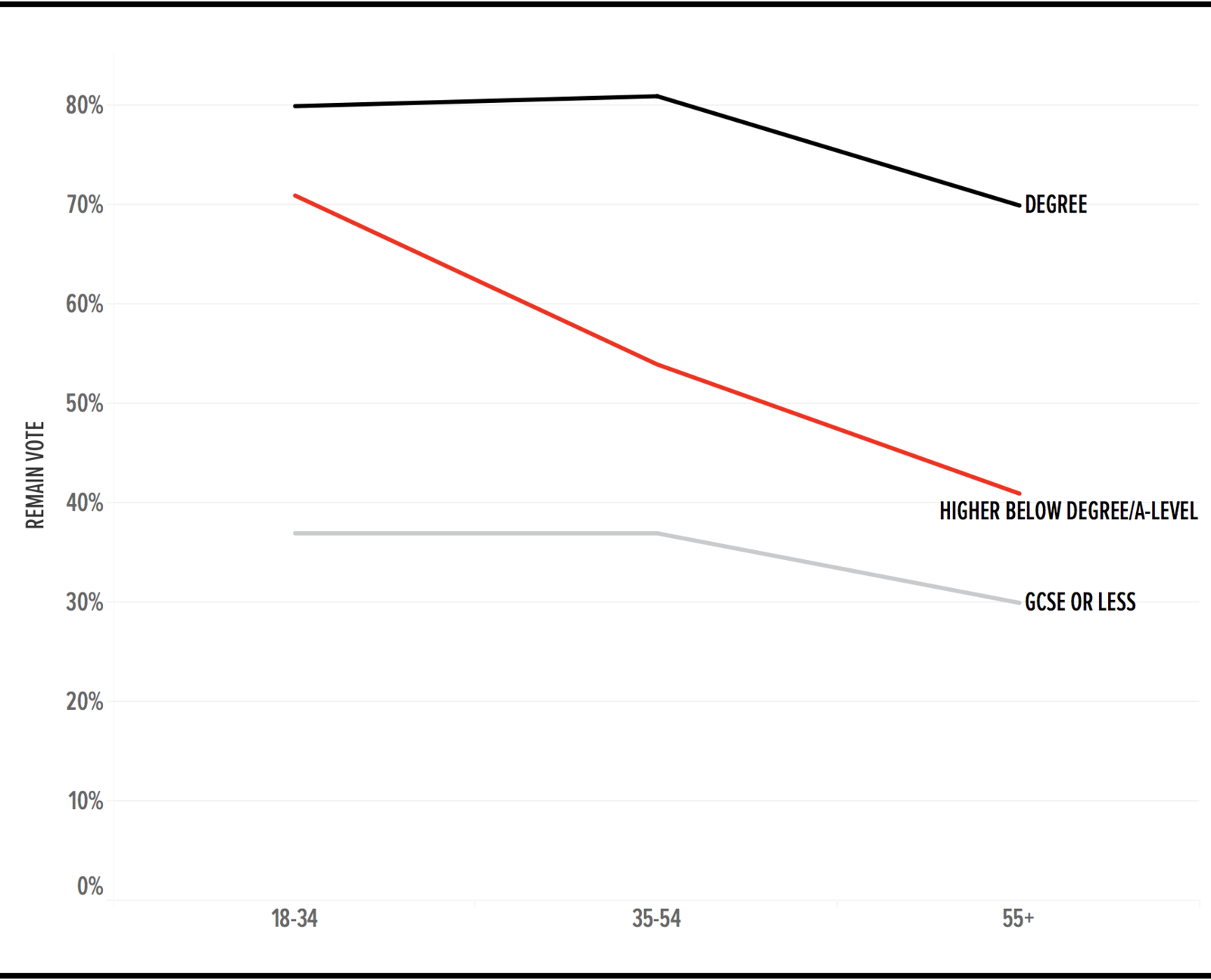

The research also showed just how significant the educational divide was in the Brexit vote – it proved even more important to the vote's outcome than the much-discussed generational divide on the EU.

Remain vote, broken down by age and educational status.

As the above chart shows, someone over 55 with a degree was just as likely to vote Remain as a young adult with only A-levels, and almost twice as likely to vote Remain as a young adult with education at GCSE level or lower.

The one group where age proved more significant than education was people with A-levels or equivalent but no GCSEs, where young adults were almost twice as likely as their older counterparts to vote Remain.

Overall, the research leaves a confusing mess of positions for Britain's politicians to choose from: The country has shifted to the left, a bit, but support for tax and spend is still less than it was when Blair was prime minister. The UK strongly supports social liberalism – but borders on draconian on law and order issues. And the UK seems to support Brexit, but is deeply divided on age and educational grounds.

With a possible second election in the next 12 months, working out how to connect with Britain's changing electorate is a task politicians have to take on, and fast.