The European parliament might be getting a bad press in the UK at the moment as the Brexit debate enters its final weeks, but that's not stopping its members tackling one of the biggest issues facing humanity: Do robots pose a threat to our future?

The answer in a draft report published online appears to be yes. The parliamentarians warn that robots pose a threat to jobs, social security, "human dignity", and more, and suggest a series of steps the EU should take to get ahead of the potential risk.

The report even warns that "there is a possibility that within the space of a few decades AI could surpass human intellectual capacity in a manner which, if not prepared for, could pose a challenge to humanity's capacity to control its own creation and, consequently, perhaps also to its capacity to be in charge of its own destiny and to ensure the survival of the species."

The European parliament joins a long line of notables concerned about the future threat posed by artificial intelligence and robots. Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk were among dozens of experts who warned in an open letter last year that more attention was needed to make artificial intelligence safe, while Cambridge University's Centre for the Study of Existential Risk counts AI among its core research areas. It warns:

Even very simple algorithms, such as those implicated in the 2010 financial flash crash, demonstrate the difficulty in designing safe goals and controls for AI; goals and controls that prevent unexpected catastrophic behaviours and interactions from occurring. With the level of power, autonomy, and generality of AI expected to increase in coming years and decades, forward planning and research to avoid unexpected catastrophic consequences is essential.

So: Is the risk real, what will it look like, and how will it begin? Wonder no longer.

First, the robots will take your chores

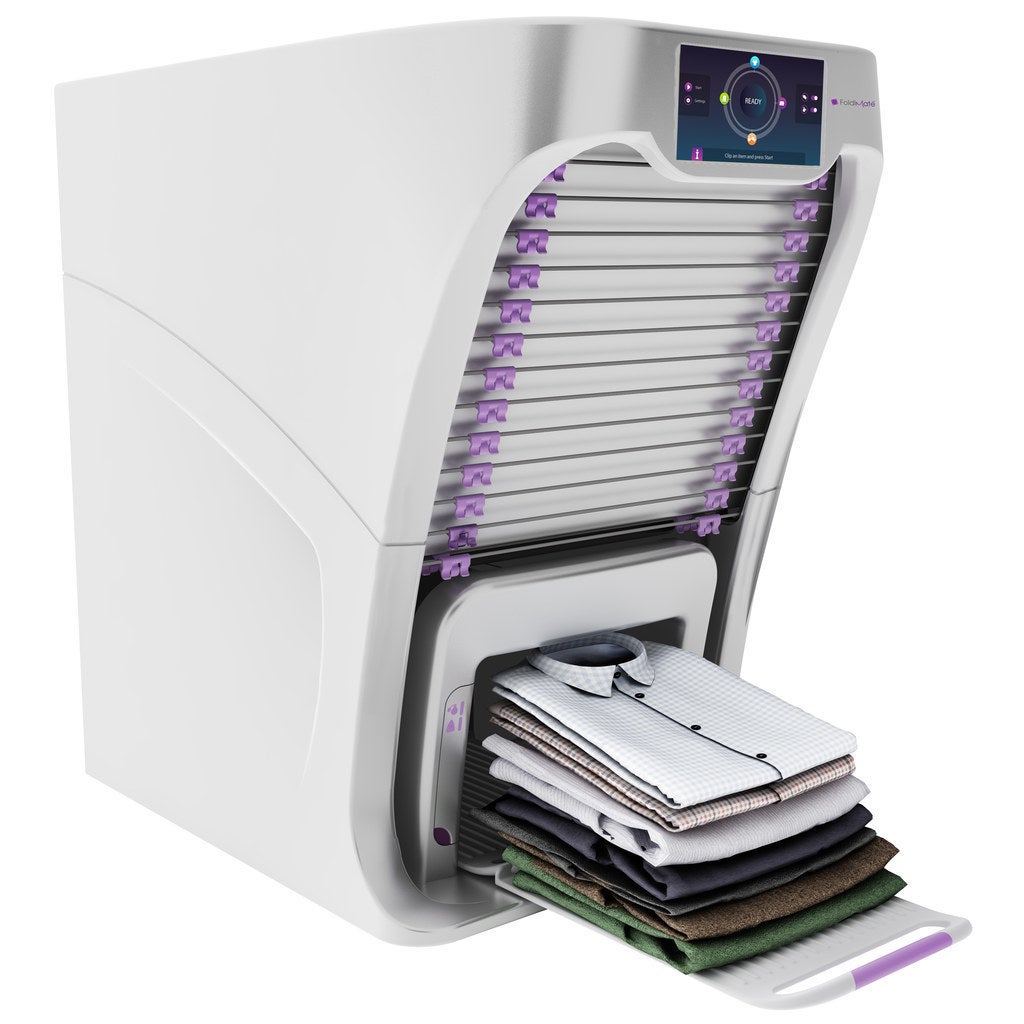

The FoldiMate ironing "robot", which can iron and fold up to 15 shirts or trousers at a time and is available for a mere $850.

The first step of the robot revolution seems pretty good, to be honest. We're starting to see a variety of household robots begin to take some of the least interesting household chores off our hands.

Some, like the FoldiMate above, barely qualify as robots at all. This automatic ironing device is pretty clever (I don't really know how to fold a shirt, so it's ahead of me), but it relies on you to tell it what you've clipped in and so doesn't have all that much AI or autonomy – and it's not connected to the internet.

A little higher up the AI rung is something like the Roomba, which has been around for more than a decade in different iterations. It's now capable of autonomously vacuuming your house, avoiding obstacles (including humans and pets), and remembering where it's been, and even returns itself to its charging station when it's finished.

The newer models are even internet-connected, which today means you can tell your robot servant to clean your house while you're fecklessly drinking in a bar productively working in your office, but in a future dominated by an all-powerful internet-connected AI may leave you vulnerable to attacks on your ankles by a vacuum cleaner hell-bent on the subjugation of humanity. You've been warned.

Next, they'll take your job

This is by far the most immediate and real threat robots pose to most of us in the short term. Anyone from a manufacturing town in the Western world will be aware of how robots and automation have meant that factories which used to require thousands of workers now often need only dozens.

This trend has started to shift to jobs in the service industry – including increasingly highly skilled ones. Supermarkets are saving on wage costs by replacing some of their checkout operators with robotic self-checkouts. Call centre staff worldwide have been replaced with voice-recognition AI systems (often to the chagrin of customers). Pizza Hut is trialling robot waiters in some of its restaurants in Asia. Hotels are using robots to deliver room service. And even cowboys face being (partially) replaced by intelligent cattle-monitoring robots.

Even the most highly skilled of service industry jobs are at risk. Lawyers – that most sympathetic of professions – may be at risk too, as one law firm is trialling a robotic lawyer to assist in its bankruptcy practice. And, terrifyingly, even journalists may be at risk, as numerous outlets deploy increasingly sophisticated AI reporters to write straightforward financial stories.

On one level, jobs being made obsolete by technology is a story as old as capitalism itself. After all, once almost everyone worked in agriculture, but now in the UK just 2% of people do. But across the world many manufacturing or mining communities struggle for decades after their main employer collapses. And if robots could eventually do all of those jobs better than humans could, what's left for us?

The draft European report adds an extra warning:

[T]he development of robotics and AI may result in a large part of the work now done by humans being taken over by robots, so raising concerns about the future of employment and the viability of social security systems if the current basis of taxation is maintained, creating the potential for increased inequality in the distribution of wealth and influence

In other words: Workers pay tax, robots don't. So not only could we all be jobless, but we might lose any safety nets – benefits, pensions, retraining – we had too. This one is a fairly serious and credible risk in the short and medium term.

Still, we'll always have love...right?

Then they'll take your lover

Oh.

There are potential benefits to having sex with robots, some could argue, including reducing the risk of STI transmission (with, er, proper cleaning).

But there are risks too, one of which is that many of us could get so attached to "sex" robots that we won't form relationships with fellow humans. That may seem an extreme risk, but people are capable of anthropomorphising pretty much anything. A woman claims she fell in love for 29 years with the Berlin Wall. Men fairly regularly claim to fall in love with inanimate sex dolls. And "mechanophilia" – falling in love (or at least having "sex" with) cars, bicycles, trains, or planes – is unfortunately a thing.

If you imagine a sex robot with sophisticated AI who could also simulate conversation, companionship and affection – perhaps tailored exactly to what you uniquely would look for in a partner – it's not difficult to imagine robots starting to replace real, flawed humans as objects of affection.

Such a robot is ahead of what's available today, but may not be too far off. Shelly Ronen, a PhD student at NYU who studies the field, spoke to BuzzFeed's Internet Explorer podcast about this topic, saying:

It's not far off. It's not available exactly today. There is one company in New Jersey called True Companions – which is a very interesting name – and they have what they consider to be the world's first sex robot that's been commercially available for a number of years now.

She is available in a number of different personalities so you can... I believe she has some kooky little names like Mature Martha or Wild Wendy, so there are different personalities that have different pre-programmed speech, things like that.

The rise of robot lovers, if they're so good, doesn't bode well for breeding a new generation of humans. That's another concern the European parliamentarians – in very general terms – warned of, as robots replace our friends and our partners:

[T]he 'soft impacts' on human dignity may be difficult to estimate, but will still need to be considered if and when robots replace human care and companionship, and whereas questions of human dignity also can arise in the context of 'repairing' or enhancing human beings.

Finally, they'll take your life (maybe)

Some of the most sophisticated AI systems in the world right now work in surveillance and in military equipment, whether it's facial recognition, drone control, or analysis of bulk surveillance equipment.

Any significant piece of military hardware is heavily stacked with advanced AI, and lots of it is directly hooked up to serious weaponry. While the AI in such equipment is very specialised – not the generalised AI of robots-vs-humans dystopians – it's not hard for these bits of gear to be an obvious area of concern when thinking about the risks of "general" AI – computers with the fluid intelligence of humans.

Military and intelligence agency networks are already heavily isolated from the general internet, for fear of hackers, so would not necessarily pose an immediate risk should a malevolent AI gain access to (or control of) portions of the internet, but they're far from the only things AIs are hooked up to that could be dangerous: Computers sit at the heart of the power grid, of factories, of the networks in our homes, of air traffic control, traffic light systems, and far more.

And that's before we start introducing internet-connected self-driving cars to the mass market.

If all of these things could think, and they all agreed that humans were superfluous to requirements, it's fairly obvious we'd have problems, fast. But such a situation would rely on an AI far beyond current capabilities, and far beyond our own intelligence. Why do some people seem to think that could happen relatively quickly?

Here comes the science part

Robots potentially destroying our careers and love lives doesn't require AI to advance all that much beyond where it is today. But the really outlandish death-to-humanity scenarios rely on computers developing general (or fluid) intelligence beyond our own, and then accidentally or by intent turning it against humanity.

Almost all applications of AI and machine learning used today (things like Wolfram Alpha, or Google Translate, or certain video games) are highly specialised forms of intelligence only useful within fixed worlds with fixed rules.

The recent triumph for Google DeepMind's AlphaGo computer in beating the world champion at Go was due to another specialised AI, but one that was more sophisticated: Whereas beating a chess grandmaster could be done by working out all the mathematical possibilities on the board, Go's complexity meant this wasn't possible even for a supercomputer. Instead, the software had to learn in a way much more like a human – a much more sophisticated and significant AI development, if still an early one.

Progress in this area is slow and expensive. But there's a popular theory that suggests that once we hit a certain stage, everything could happen very quickly indeed. This theory is known as the singularity. The logic runs as follows:

- An intelligent entity (humanity, arguably) manages to create an AI with general intelligence greater than our own.

- That AI, by accident or design, turns its focus on also creating an intelligence greater than itself.

- Logically, if humanity can create something more intelligent than itself, that entity will be able to do the same – and possibly quicker and better.

- The new, even better AI, then repeats the task, as does its successor, as does its successor, and so on.

- Very quickly, we now have an AI with an intelligence far greater than our own.

This logic suggests at least the possibility for AI to grow in power exponentially, and quite quickly. Computing is no stranger to such astronomical growth: Today's computers have millions or billions times the processing power of those of 30 or 40 years ago.

If the reasoning for the singularity is correct, we could face superintelligent AI that far surpasses humanity within our lifetimes. But there's no guarantee it is. It's not clear any ethical researcher would want to try to trigger such a risky chain reaction, and intelligence is an ill-defined concept that may hit hard limits – there's no guarantee the exponential process would work in practice. Computers may hit physical limits based on hardware or architecture; "intelligence" may have diminishing returns.

But if we regard the singularity as at least plausible (and a lot of computer scientists and AI experts do) then the remaining hope for humanity is some hardwired code of behaviour for artificial intelligence and robots. Can we manage that?

"A robot may not harm humanity"

The best known rules for governing AI were developed by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov in the 1940s for the AIs in his novels. They were revised by Asimov through his lifetime, and often drawn upon by others – the draft European parliament report even cites them. There are three rules, plus a fourth (rule zero) that was added later:

(1) A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.(2) A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

(3) A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws

and (0) A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

Problem solved! All we've got to do is get these rules into our AI systems, and humanity is safe and well. Except – as Europe's parliamentarians and many others realised – it's not all that simple.

These might be easy rules for us to understand (if not to follow), but they're essentially impossible to program into any existing computer or AI in any meaningful or systematic way. The report dodges this issue by artfully placing the rules upon those designing AI:

Until such time, if ever, that robots become or are made self-aware, Asimov's Laws must be regarded as being directed at the designers, producers and operators of robots, since those laws cannot be converted into machine code

Clever. But totally ineffective, as guidance to humans can never translate into infallible rules in the systems they create. As anyone who has ever used any computer at all will realise, bugs get everywhere and systems don't work as intended by their designers.

But even if they did, advocates of Asimov's laws miss a key fact: He was a science-fiction writer, and the bulk of his canon shows the potential for chaos and calamity even with often-compassionate AIs subject to the laws. One simple example is a robot's creators defining "human" to exclude a given ethnic group, allowing robots to engage in ethnic cleansing with ease.

More broadly, as this excellent debunk of the Asimov laws from the Brookings Institute details, the laws would be awful in practice: Would we really want any AI to obey any order from any human? Given how many AI systems are used by the military, would we ever allow rule one to come into existence?

Multiple panels and experts are working on the problem of AI ethics, but given that humanity lacks a universal agreed set of ethics and morality, and that's for an intelligence we understand at least to an extent, it seems likely (or at least possible) that technology could outpace our ability to set boundaries. Isaac Asimov isn't going to save us.

Even ethical robots might hate us

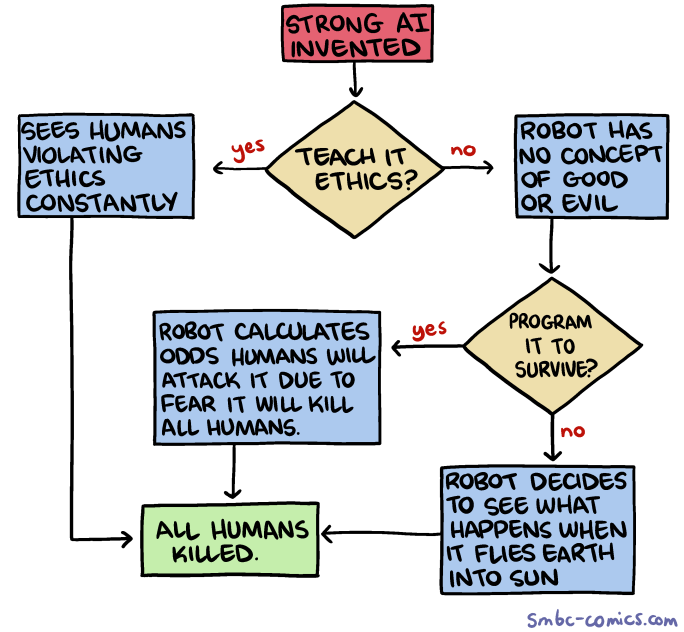

Let's imagine we somehow managed to instil robots with a code of ethics similar to Asimov's. We wouldn't necessarily be out of the woods – the problem is, humanity is awful (really, just check the headlines), and AI might not like us not living up to its standards, as SMBC's Zach Weinersmith illustrates in this flow chart:

If we choose to be less pessimistic than Weinersmith, but agree ethics won't save us, what options do we have left?

When in doubt, side with the AI

One possibility for the future is that we exist in a world with sophisticated AI that is either friendly or ambivalent to humans – or only hostile to humans which threaten its own existence. That raises the possibility of doing what comes naturally to so many of us: siding with the biggest, scariest kid/person/entity in the room.

This chain of reasoning hits its logical end in what is almost definitely the worst argument on the internet: Roko's Basilisk, which suggests you should give all the money and help you can spare to help develop AI right now – just in case. Here is (very roughly) the logic of the argument. There is a TL;DR below if you would like to skip it:

- There is a chance that at some point in the future we will develop a super-intelligent AI with humanity's best interests at heart.

- That AI will be able to prevent death, suffering, and existential threats to humanity, and will work tirelessly to do so.

- As a result, that AI knows its own existence is incredibly important to help humanity: It must be allowed to survive, it must be allowed to work, and it must be allowed to come into existence as soon as possible, to do the most good.

- One thing the AI could do to help itself get created faster is punish anyone who realised a superpowerful AI could help humanity but either tried to stop it coming into being or did nothing to help it.

- By retrospectively horribly punishing those people (or punishing a simulation of them if they're long dead), it would incentivise anyone following this chain of logic to help create the AI. (We are nearly done. I did warn you this argument is awful.)

- As a result, if you know about this argument, you should do anything you can to help AI be created, or you will be on the list for terrible punishment. Sorry for telling you about it, if it turns out not to be nonsense.

The TL;DR: Roko's Basilisk is a chain letter for nerds about why they/we should switch sides to team AI right now, just in case.

For those who don't want to side with our future robot overlords, what practical measures are there to prevent the rise of AI causing the fall of humanity?

The fightback begins. Maybe

The first threats to note are the practical ones: Robots really are going to threaten a lot of jobs we assume aren't at risk from automation at the moment, and the consequences of the huge joblessness caused by factory shutdowns and automation are felt to this day. On this one we know the risks are real and we've seen the warning signs: If we're going to automate, we need to get better at supporting people in the affected trades and professions.

The next risk down the line is that of robots replacing friends and lovers, which touches issues not that dissimilar to conversations around porn, internet use ("teens are always on their phones"), and relationships now – this is probably a problem we would tackle in similar ways to those issues: education and counselling.

Trying to prevent the most outlandish scenarios is the focus of academic research, US policymaking, and the draft European parliament response. They want international ethical commissions, EU-wide rules on robots (including self-driving cars), standards, and a European Agency for Robotics. There are a lot of bureaucratic hoops to jump through before any of these things happen though.

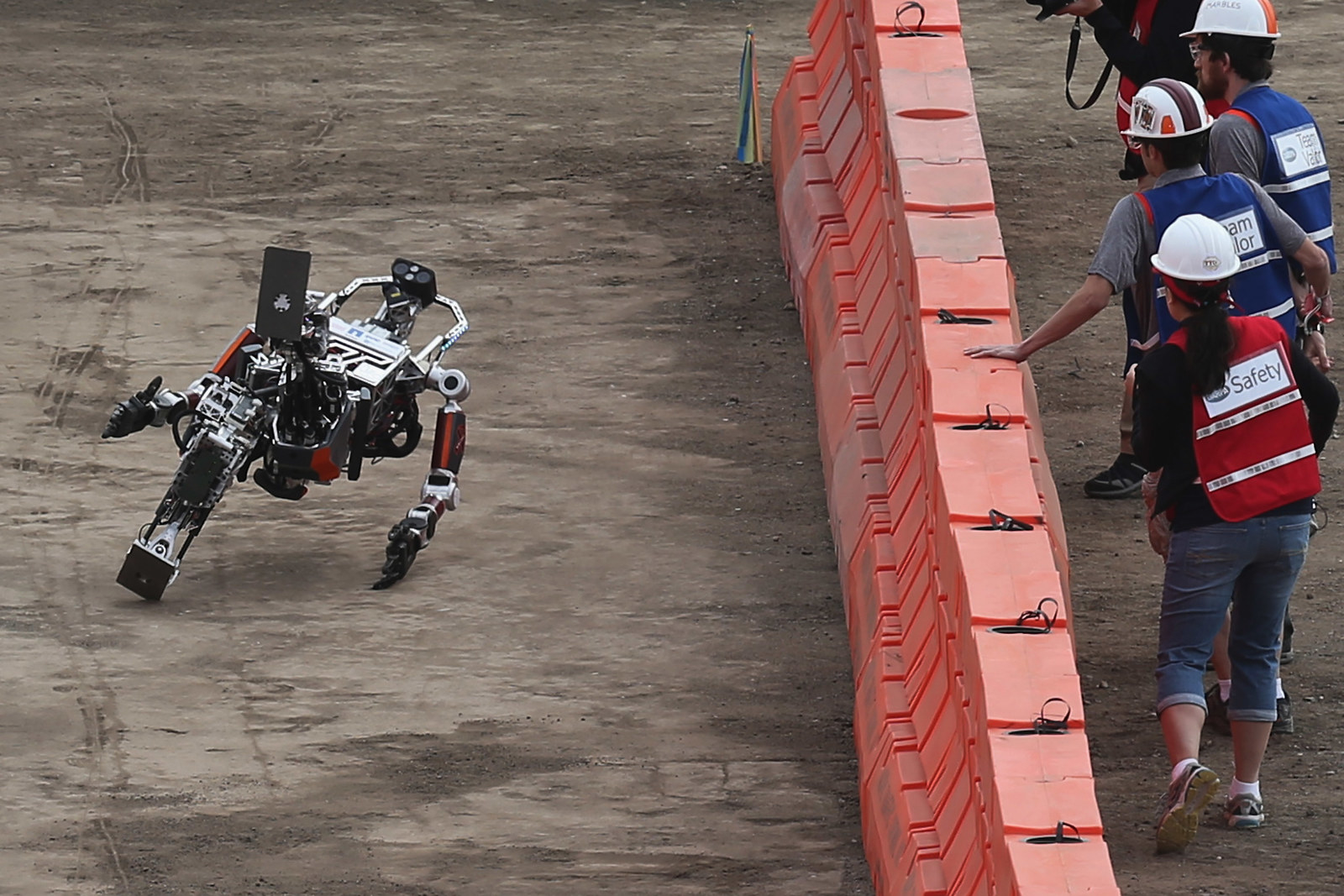

What about if the doomsday scenarios do happen? What do we do if sophisticated robots want us dead? This one is trickier. Given robots still struggle with walking, the old Doctor Who trick of running upstairs would work for quite some time against Terminator-style killer robots. But given AI would likely control drones, power supply, cars, and more, that hope might be short-lived.

Realistically, if there is hope, it lies in batteries. Or, more precisely, how rubbish battery technology is. AI and robots need power and we don't. Our best hope post-crisis would probably rely on trying to cut off power supplies, or networks, and isolate issues that way. Unfortunately, this also resembles the premise of The Matrix, and didn't end well for humanity in that instance (great film, incidentally. Too bad they never made any sequels).

There's also a particularly dire scenario for humanity: Robots may figure out whatever witchcraft powered the Nokia 9210 without a charge, seemingly for months on end. If that happens, it's game over. We've had a good ride.