There is no one in Hollywood like Steven Spielberg. The highest-grossing director in history has covered everything from the realities of terrorism (Munich) to the fantasy of dinosaurs in modern-day life (Jurassic Park), the horrors of slavery (Amistad) to adventures in archeology (Indiana Jones), and the tragedy of the Holocaust (Schindler's List) to terrifying aliens (Close Encounters of the Third Kind) and sweet ones (E.T. The Extra Terrestrial), too. He’s worked with Harrison Ford, Sean Connery, Leonardo DiCaprio, Richard Dreyfuss, and Tom Cruise, but the actor Spielberg has collaborated with most in recent years is Tom Hanks.

The pair's last film as director-actor, The Terminal, was released more than 10 years ago. And now, they’re back with Bridge of Spies, in theaters Oct. 16. "We never took a hiatus,” Spielberg assured BuzzFeed News while sitting with Hanks at the Ritz-Carlton in New York. "In between The Terminal and Bridge of Spies, we produced two huge miniseries. Something's always happening."

That latest something does what these two do best: captures the intensity, humor, drama, and joy of a historical event. With Bridge of Spies, they turn to real-life insurance lawyer James Donovan, who was tasked with representing alleged Soviet spy Rudolf Abel, and then asked to conduct negotiations with the Soviets for the release of an American pilot, Gary Powers, in exchange for Abel.

A week before the release of their fourth movie as director-actor, Spielberg and Hanks sat down with BuzzFeed News for an intimate conversation during which they looked back on some of the movies that made them who they are in Hollywood, including ones they worked on together.

Below, find out which actor scared Spielberg most, the advice he didn’t listen to, why Steve McQueen turned him down, the only movie of his he likes to watch, and why Jaws was almost the end of him. (And click here for Hanks’s interview.)

Duel

Spielberg’s first feature-length film was this 1971 thriller, based on Richard Matheson’s short story of the same name. Up until that point, Spielberg had only professionally directed episodic television, including Night Gallery, The Name of the Game, and Columbo. He was only 24 when Duel aired as ABC’s Movie of the Week, centering on David Mann (Dennis Weaver), a middle-aged salesman on a business trip who’s stalked on a remote two-lane road in the California desert by a tanker truck and its unknown driver.

Steven Spielberg: I guess the first feature I did was Duel, which was a television movie.

Tom Hanks: Now how did you get that job?

SS: I got the job because my secretary, I guess she read Playboy and she read this short story by Richard Matheson called Duel. And she said, “I read something that I know you should direct.” So I read the story and I thought it was great and I instantly wanted to direct it. But we didn't know who owned the rights and then she did some detective work and learned that it was not a feature film, it was about to become a television movie for ABC Movie of the Week.

TH: The ABC Movies of the Week, yeah. On Tuesday nights.

SS: Exactly. And a man named George Eckstein was the producer. I had already been a director of episodic television for two and a half, three years, and I had just done the pilot for Columbo.

TH: Wait, you did the pilot for Columbo?!

SS: I did, yeah.

TH: See? You find out stuff you never knew. That's a major important piece... I mean, you kicked off the entire Columbo franchise.

SS: It was a rough cut, it hadn't aired, and I went over to George Eckstein's office and I asked him if he'd look at the rough cut of my Columbo. He said he would, and he liked it enough to hire me to do basically what became my first movie. Because even though it was shown on television in America and it was successful here, the studio wanted to release it overseas in movie theaters. So I got to leave America for the first time in my life and I went to Italy and Spain and Germany and France and England and I traveled with the film.

TH: Nothing like that had ever been seen anywhere and I hadn't even seen a motion picture like that before. I read about it because in the Oakland Tribune, the TV columnist said, “There's a thing on TV tonight that you really must see because there's never been anything like it.” So I watched that on Tuesday night. I watched Duel on the ABC Movie of the Week. And it truly was.

SS: They only gave me like nine days to shoot a 74-minute TV movie and I did it in 11 and got in big trouble with ABC. I went two days over and oh my god, did they give me a bollocking.

TH: Did anybody come up to you and give you an old-school piece of advice?

SS: Yeah, and I didn't listen to it. The old-school piece of advice was, “Hey, kid. You're making a big mistake shooting this thing on location. Why don't we just go back to the studio where it's safe and quiet and controllable?” And I insisted that the audience wouldn't believe a truck was chasing a car unless it was a real truck, a real car, and a real highway.

TH: Were you nervous?

SS: I was nervous. And then to qualify it for a feature overseas, it had to be 90 minutes. So they sent me back and they said, “OK, just add another 13, 14 minutes to your television movie to make it a theatrical film.” So I made up these scenes — I made up this scene where Dennis comes to a railroad crossing, and there's a train crossing...

TH: Oh yeah! Yeah!

SS: The truck pulls up behind him and starts pushing the car into the moving train.

TH: You made that up in order to get to the 90 minutes?

SS: And there were about five other scenes, too.

TH: He proved himself to be Steven Spielberg very early on.

SS: You know, when you're first starting out, every day is terrifying. And every day doesn't feel long enough, but we were shooting for 14-, 15-hour days.

TH: Who scared the living daylights out of you? Who was one of the first cast members who you had to work with... Did you always know how to talk to them or...?

SS: Yeah, I can only talk about the ones who are dead because I don't want to hurt anyone's feelings if they're still alive. Well, you know, everybody presumed that Joan Crawford scared the hell out of me. That was the first professional show I ever did.

TH: That was Night Gallery.

SS: Yeah. I was 22 years old, and it was [Sid] Sheinberg, who discovered me.

TH: There's a great picture of you talking to her and you've got that Panavision Finder. And it looks like you're bending over to ask for something. She didn't scare you?

SS: I was terrified. I was terrified. At first, she terrified me — just the idea that NBC and Universal were casting her and they were signing me. I had never directed anybody with a SAG card. And so the first SAG member is Joan Crawford that I've ever directed.

TH: Wow.

SS: I came onto that thing a complete greenhorn. And I must say, she didn't know me, she never heard of me, and she said, “Come pick me up on Franklin Avenue. There's this house I'm staying at, and take me to supper.” And I got to the door — John Badham came with me, he was the associate producer on this — and she opened the door and invited us in and took one look at me, and the first thing she said was, “Well, we can't go out to dinner. Everyone will think you're my grandson.” And then she corrected herself, “My son!”

TH: Ha! Ha! Ha!

SS: So we had a meeting at her house, and then we got to the set a couple days later to start shooting, and she treated me like a complete professional.

TH: Wow. Probably because she was such a professional.

SS: She was a complete pro. And she treated me like Henry King or George Marshall, any of those great warhorse-type directors that did such distinguished work, some of them with her.

Then, years later, probably like 10 years after her death, [studio executive] Lew Wasserman and I are having lunch together at The Commissary and he said, “Did I ever tell you my Joan Crawford story?” And I said, “No! What's your Joan Crawford story?” “Well, remember when you met her at her place?” I said, “Yeah. I remember when I met her.” “Well, I guess you guys left an hour later and she called me, she said, ‘How dare you treat me this way! You assign me this kid — he's got acne, and he's got long hair, and he was wearing love beads around his neck...’”

TH: Oh yeah. The love beads.

SS: It was 1968, come on. Look, everybody wore love beads. And she just said, “I'm not working with him.” And Wasserman simply said, “OK, Joan. We believe in the kid. We'll find someone else to play your role.”

TH: Whoa! Lew Wasserman. Wow.

SS: He told me that story, and I just couldn't believe it. That was an amazing story.

Jaws

Spielberg created the summer blockbuster in 1975 with Jaws. He was reportedly given a $3.5 million budget and a shooting schedule of 55 days. Instead, the movie allegedly cost $9 million and shot for 159 days. But Jaws, which was based on Peter Benchley's 1974 novel of the same name, eventually became the highest-grossing worldwide film of all time...until Star Wars came along two years later and ousted it.

TH: So Jaws comes along, Richard Dreyfuss is probably the least likely Hollywood leading man there is, although Richard is in American Graffiti, he's in Jaws, and he's in Close Encounters — three movies that literally wrote the book on what movies could be.

SS: On Jaws, I had a great time with Richard. And I cast him in Jaws because I loved him in American Graffiti. That was a great character — that spark, that energy, that almost static electricity that just came off of him in American Graffiti, especially when he sees the girl in the T-Bird, when he becomes obsessed with her. He can do comedy and he can break your heart at the same time. He played this sort of entitled theologist in Jaws. He's a little bit of a spoiled brat and has this big, rich boat. And I just thought it would be a good fit. So Richard immediately committed. But on the movie, we became best friends.

TH: Well, you had a lot of hang time.

SS: Yes — 100 days over schedule, all the water, it was insane. I almost got fired probably 19 times. It was almost my epilogue, you know? "He made Jaws." Nothing has been like that. My most troubled shoot after Jaws has been nothing. It doesn't even compare. Jaws was nightmare because... I don't even know who we were. We were a bunch of upstarts, a bunch of young people who thought we could take on the ocean. You can't take on the ocean. And we thought we could do it by bringing a mechanical shark into the Atlantic Ocean and the salt water just wreaked havoc on all of the hydraulic tubes and things and the shark kept sinking.

TH: Well, Jaws changed the business, changed the technological aspect of filmmaking, lots and lots of stuff. Then Close Encounters of a Third Kind was another quantum leap in filmmaking, but with the same actor.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

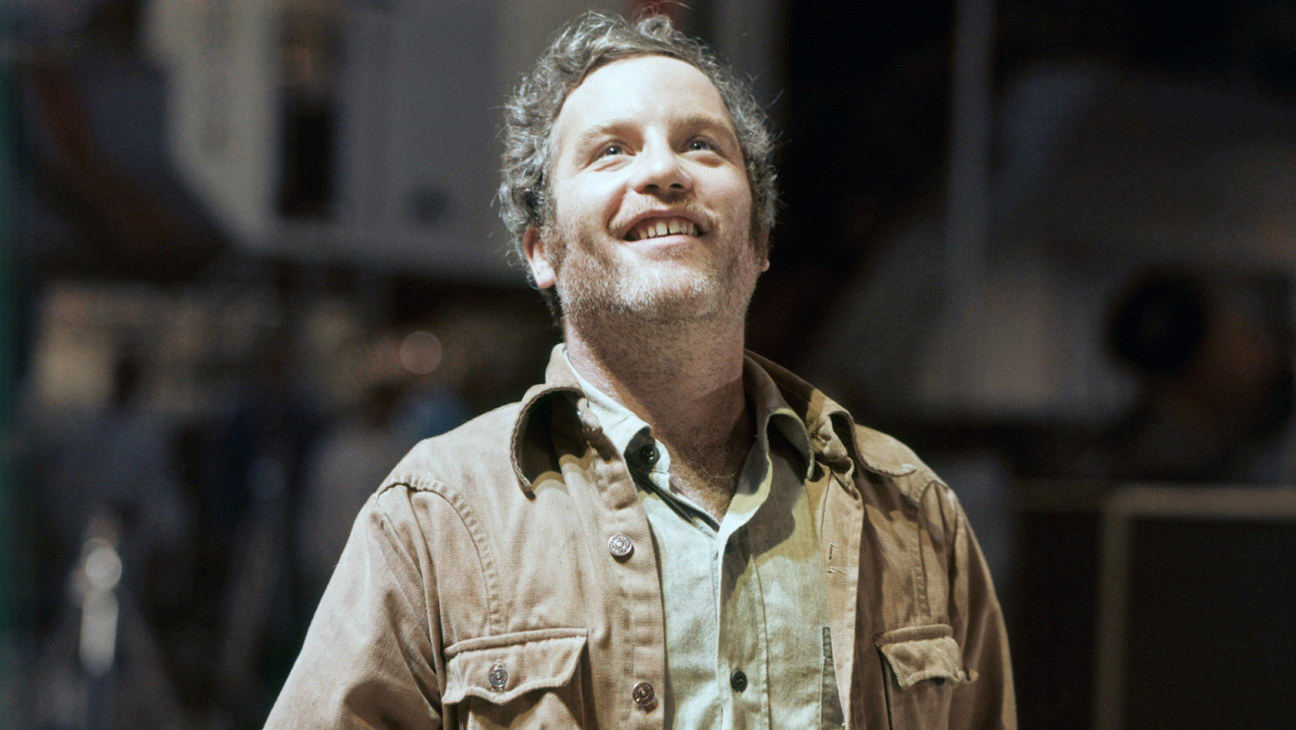

Spielberg wrote and directed this 1977 sci-fi movie, which saw him team up with Dreyfuss again. The actor played leading character Roy Neary, an electrical lineman who lives in Indiana with his wife and three children. But after he encounters an unidentified flying object and becomes obsessed with figuring out what exactly he saw, he’s never the same.

TH: You and Richard worked on two movies back to back. As a guy that was going into movies, I thought, What do these two guys have going on up there?

SS: Well, Richard was the everyman in the sense that I thought if I put a person in the role of Neary — a family man who becomes obsessed with this encounter he has with something he can't understand and is implanted with an image of a weird-lookin' thing and starts making it out of shaving cream and mashed potatoes — that people would believe it. He’s somebody who looked like he should be in the audience watching the movie, not on the screen being in the movie. He was just a kind of guy that people could relate to.

But before I cast Richard, I tried Steve McQueen, I tried Gene Hackman, I went to a number of movie stars. Richard actually lobbied for the part.

TH: Now, they didn't turn it down?

SS: They all turned it down.

TH: Get out! Really?

SS: McQueen turned it down, but I became friendly with McQueen so the good news was I got to ride dirt bikes with Steve on weekends because he said no, but he discovered I rode dirt bikes and he rode dirt bikes and we became kind of friendly in that arena.

TH: Well, that's cool.

SS: But it's interesting. Steve said, "I love the script. But I can't do your movie." And I said, "Why not?" And he said, "Because the character at the end cries and I've never cried in a movie before. And you gotta get an actor that will really cry and not fake it with the glycerin in the eyes." And I said, "I'll cut it out! I'll cut it out! I'll cut out the scene where he's crying." And he said, "Nope. You gotta have the integrity to get an actor who will give you everything. And emotionally, I don't think I can get there." That was his reason.

TH: I was amazed by that movie. At 10:30 in the morning, a friend of mine called and said, "Close Encounters, Sacramento Century Theater. I'll meet you there with the tickets." It was a life-altering thing.

Did you have a shorthand with Richard Dreyfuss, like you and I seem to have?

SS: Yeah, we did. I made three movies with Richard. Rich and I had a real shorthand. We were personal friends and our wives knew each other. Very much like…

TH: Like we did, yeah.

SS: Saving Private Ryan was the first time we really had shorthand.

TH: The first movie we ever made.

SS: And we discovered the shorthand. We didn't know we had it. We kind of discovered it by all these little what they call happy accidents.

Saving Private Ryan

Three Indiana Jones movies, two Jurassic Park installments, and Schindler’s List, and Amistad later, Spielberg and his longtime friend Hanks worked together as director and star in the 1998 war drama about the Invasion of Normandy. It was Hanks who first read the script and passed it along to Spielberg to direct, and they worried their friendship wouldn’t survive the shoot, but the opposite happened.

SS: With Private Ryan, I wanted to set every shot up like it was a documentary. We were just a movie crew, we were a movie cast, and we were taking a beach, always respecting the fact that we weren't those guys on June 6, 1944. We weren't going to give our lives. We were doing something to embrace, and to respect their sacrifice that day on that beach. But we weren't those guys. Because it was very important that everybody understood that this, after all, was a recreation — it was not the real thing. But having said that, we all believed in our own way that we were doing something that was going to live as a tribute to those who never came off that beach.

TH: Yeah. I think we all took it very, very seriously.

SS: All through the movie — not just with that beach scene, but every aspect of it.

TH: Yeah, no. There was a degree of a hallowed ground.

SS: One of things I wanted to do was give everybody a sense of really firing their weapons. I went to Michael Lantieri, who's one of our physical effects experts. And I've done a lot of movies with Michael — Jurassic Park, a lot of pictures. And I said, "Michael, can you rig blanks with some kind of a transmitter in the gun itself to the squib, so when the actor fires the gun at the appropriate amount of time, the squib goes off on the person he's shooting at?" And it freaked a lot of the actors out because in the heat of a movie war, and I say, "Action," they can't hear anything, and every time they fire their blank they see the blood hit on the other actor. That did some mental damage. I talked to Vin and it bothered Vin a lot. It bothered some of the actors because they actually thought they were shooting the other actors.

Catch Me If You Can

After Saving Private Ryan became a box office success and earned 11 Oscar nominations, including a Best Director nod and win for Spielberg, it was only a matter of time before he and Hanks teamed up again. And they did for this 2002 biographical crime drama based on the life of Frank Abagnale, who essentially stole $6 million as a con man before he turned 21. Leonardo DiCaprio signed on to play Frank Abagnale and Hanks took on the role of Carl Hanratty, the FBI bank fraud agent who eventually caught Abagnale six years after his crimes began.

SS: Catch Me If You Can is one of my favorite movies. I can't see a lot of my movies again because I keep thinking about what I should've done. There's a handful of things that I've directed that I can actually watch. And I can actually watch that movie because it's zippy. And there's really fun things in there. I mean, how could I resist not making a movie where the guy's talking about the Skyway Man. And he says, "This guy thinks he's James Bond." Then Leo gets to say the line, he looks out and says, "James" and then you cut to Goldfinger. And he says...

Both: “Bond. James Bond.”

SS: For me, that was the sell.

TH: You know, that movie...actually is not exactly what happened, but it lives up to the spirit of what Frank Abagnale would do in a different way like Bridge of Spies does, which is much more dealing with the specific. But it's very, very much that kind of loose sense feeling of abandon that Abagnale himself had. He's a fascinating man.

SS: Yeah, Abagnale's a fascinating guy and the real Frank Abagnale Jr. was with us and was a technical adviser and is actually in the movie — he's the one that comes in and handcuffs Leo's character. But that was just a complete joy.

TH: I think that movie took everybody by surprise, and I think one of the reasons was you were very much in tune with young Frank Abagnale.

SS: Yeah, because in a way, he reminded me of myself when I snuck onto the Universal lot when I was 17 years old, trying to just learn how to make movies. And that whole incursion and kind of breaking the law, trespassing, and everything that I did in my desperation to learn movies and be able to make them some day was kind of like the Frank Abagnale character. I completely related to it. Of course, I didn't go off and steal $6 million.

TH: OK, you always had movies being played in your head and I was always playing roles in my head somehow. Maybe you were like me in that you could be at a place in which everybody else was bored, but you were able to take yourself out of a class or a social circumstance and just think about movies. [laughs] I always felt as though I had this kind of like great interior persona I could just fall back on as a performer.

SS: The thing about being on the side of the camera that I love to be on is that I can have a thought in the middle of the day and I can have a crazy, off-the-wall, out-of-phase thought, some kind of an image, and if it's provocative enough, I store it away. And then I forget it. I will forget the idea, but it will come out subconsciously when I'm making a movie and I need that thought. Seven, eight, ten, twenty years later, what I put in my head, in my brain file and totally forgot, pops up and I remember the idea and I use it on that film. So it's interesting that filmmakers who have an active imagination can bank a lot of great ideas and then just forget about them because they will serve you well in years to come.

This interview has been edited and condensed.