Last week, when the singer Björk effectively accused the director Lars von Trier of sexual harassment, it wasn’t necessarily a surprise to anyone who’s been following his career. Björk’s ordeal on the set of Dancer in the Dark (in a role that earned her a Best Actress Award at Cannes) was already partially known, and von Trier has long cultivated an image of arrogance and uncompromising dominance in filmmaking; he denies harassing Björk, but does not deny that their relationship was fraught. He also seems obsessed with, as movie critic Dana Stevens wrote in Slate in 2009, making movies “in which a passive, vulnerable, often mentally unstable woman is gradually driven crazy, and sometimes killed.” He once said in an interview, in regard to his reputation, “I don't think I've misused anybody, but I could, of course. And I could be tempted to."

Von Trier is also considered by many to be one of the best film directors in the world. He has been awarded the Palme D’Or, the Grand Prix, and the Jury Prize at Cannes Film Festival. He consistently works with some of the top actors in the industry, from Nicole Kidman to Kirsten Dunst, and was a cofounder of an influential minimalist film movement called Dogme 95. Although one of that movement’s rules was that “the director must not be credited,” it has always been hard to separate the man himself from any of his award-winning works. This is often attributed to his unique cinematic talents, but as the Guardian noted in 2012 — while naming him one of the greatest living directors — von Trier is as known for his “juvenile love of provocation” as he is for his artistic impact.

Von Trier’s directing style has been described as “a gift and a curse” to the women who star in his films, for the fact that it can result in major acting awards. But in 2011, Björk challenged the idea that the performances of women in his films were evidence of von Trier’s artistry, asserting instead that “he needs a female to provide his work soul. And he envies them and hates them for it. So he has to destroy them during the filming. And hide the evidence.”

Like some other male directors in Hollywood (think of Quentin Tarantino defending his use of the “n-word” or Gasper Noé bragging about shooting a film while high on cocaine), von Trier courts controversy and successfully promotes the idea that his wild, transgressive imagination is worth all the terribly “juvenile” things he might do while exploring it. But he hasn’t been ostracized in the industry for jokes about sympathizing with Hitler, or his legacy of pushing women past their limits on set. Each story of von Trier’s offensive or oppressive behavior over the years has just seemed to contribute to the perception that he is some kind of demented visionary with, as MovieMaker magazine puts it, a “playful instinct to provoke and experiment.”

The line between provocateur and abuser remains very much blurred in the culture of film at large, and certainly in how we talk about directing movies. And producers, critics, and audiences have not just watched but applauded over the decades as men who direct cross over it again and again. More often than not, in an industry dominated by men who worship other men, those behind the camera who “provoke” the women they work with — from Alfred Hitchcock to Stanley Kubrick to David O. Russell — are given the benefit of the doubt over the women who suffer under that so-called provocation, or at least the blessing of endless second chances.

In many of these cases, the alleged abuse is emotional or verbal, rather than sexual. But in the wake of the tide of allegations against producer Harvey Weinstein, now followed by Björk’s implied statement on von Trier and the staggering number of women (more than 200) who have accused director James Toback of harassment, there is a new and substantial pressure on those in power in Hollywood to broadly transform the culture of filmmaking. There are some signs that Weinstein’s downfall might already be impacting the dominance of white men in the industry. And if disrupting the status quo is the goal, it’s past time for cinema’s elite to explore how the deification of men who direct might itself be contributing to an environment ripe for abuse.

After all, not everyone gets to be a provocateur, or a “juvenile” genius, on a film set. And the long leash men specifically receive for their “risky” artistic exploration has too often shown a tendency to morph into a cosigning of the exploitation of power. In fact, in the one-sided history of cinema, so many directors who abuse women in one way or another have been able to find repeated success and acclaim that abuse is not just systematically overlooked — it is often treated as a sign of a man’s genius.

The dominance of white men is the centuries-long story of the world we live in, and the movies have long played a role in celebrating and maintaining patriarchy. For nearly 100 years, Americans have gone to the cinema, sat in the darkness beneath a massive screen, and stared up at the dreams of men.

Laura Mulvey wrote about cinema’s “male gaze” in her influential 1973 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” and feminist theorists of color like bell hooks have been expanding on similar ideas for decades, but it’s clear that much of the industry never got the memos — or chose not to read them. Because even if women have been included a (wee) bit more behind the camera in 2017, the cinematic perspective of straight white men is still largely considered the better one in Hollywood and beyond — the more artistic and more meaningful lens through which to see the world.

For instance, men directed 21 of the New York Times’ “25 Best Films of the 21st Century So Far.” All of the “Top Arthouse movies” in a 2013 list at the Guardian were directed by men, and Taste of Cinema’s 2014 list of “the most innovative filmmakers working today” is all men too. Only two (white) women have ever won Best Director at Cannes in its 71-year history, and only one (white) woman has ever won Best Director at the Oscars. But it’s not just who gets recognized as “great” that bears out a gender bias, but how the mainstream language around directing film remains centered on expressions of masculinity as well.

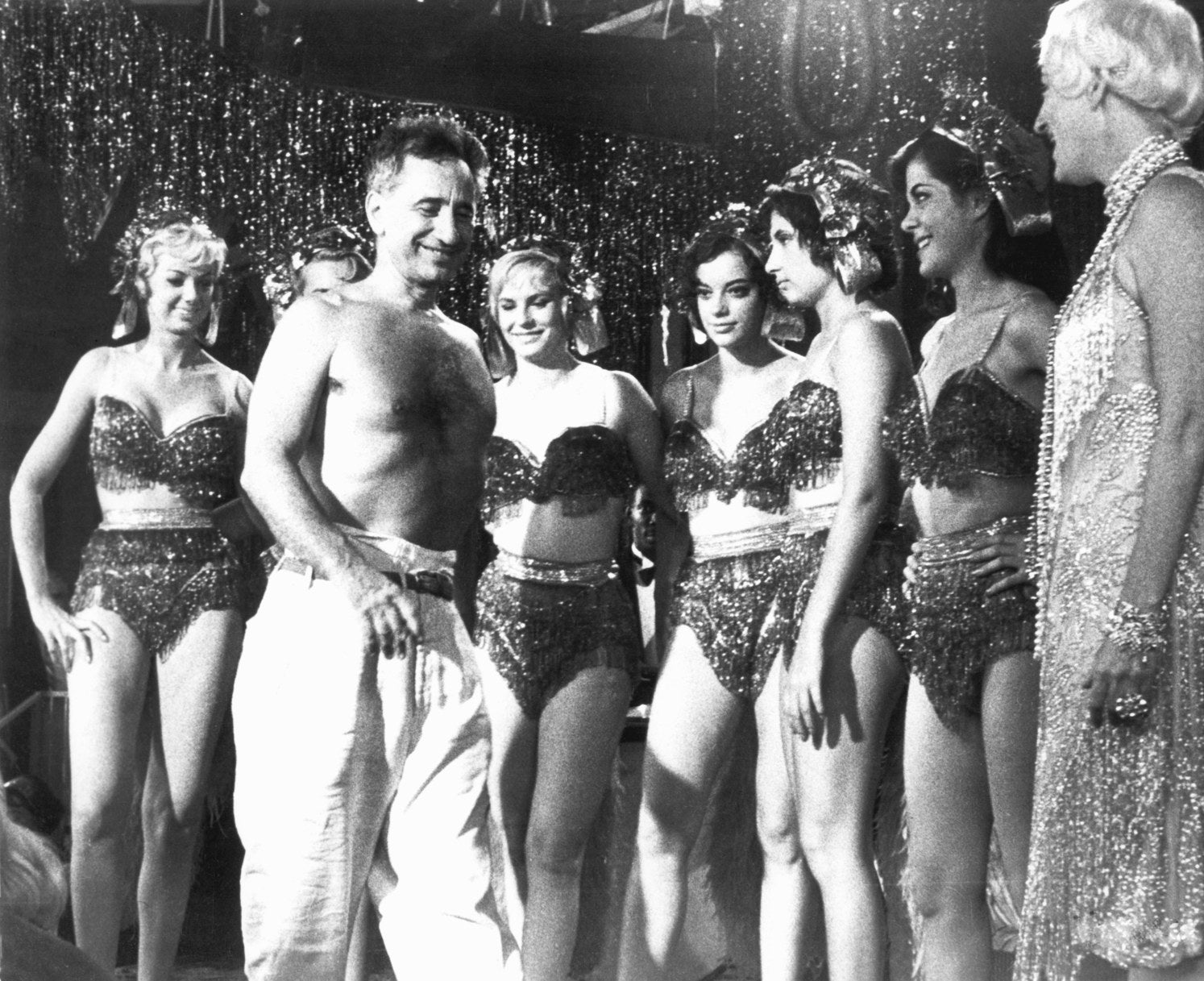

The same year that Mulvey published her landmark work, the Oscar-winning director Elia Kazan (who made A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront) gave a speech at Wesleyan University titled “What Makes a Director.” He begins by asking three rhetorical questions: “How must he educate himself? Of what skills is his craft made? What kind of man must he be?” He goes on to give the assembled students a litany of advice, including the eyebrow-raising suggestion that a man who directs “must be an authority” on “lovemaking.”

Kazan’s assertion that filmmaking requires masculinity and is itself an expression of worldly manhood has more or less remained the accepted norm to this day in Hollywood, despite the best efforts of feminists and women behind the camera to open our eyes to how narrow that masculine perspective really is. It reflects not only the persistence of “auteur theory,” the popular idea that directors are the true “authors” of film — which first elevated men like Hitchcock and Howard Hawks to the level of respected artists — but the broader concept that greatness in cinema is necessarily tied to dominance over a film’s production.

Bernardo Bertolucci, a two-time Academy Award winner, embodied this mentality when he confessed to directing a rape scene in 1972’s Last Tango in Paris without the full consent of star Maria Schneider. Schneider, who appeared opposite Marlon Brando, said in 2007 that although the assault in the film was simulated, “I felt humiliated and to be honest, I felt a little raped.” The Italian director had no qualms about sharing in 2016 that he intentionally withheld information about the scene in order to remain in complete control: "I didn't want Maria to act her humiliation her rage, I wanted her … to feel … the rage and humiliation.”

Men aren’t just given the majority of opportunities in cinema, but are rewarded for making films in a way that reinforces their power and control in society, which we see in the way authoritarian filmmaking itself is glorified. Whether it’s the famously warlike atmosphere of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, or the “unbearable conditions” reported by the actors of the Palme D’Or–winning Blue Is the Warmest Color, many of the most highly praised films are those that display, in their “craft,” an adherence to hypermasculine ideals of power. And if the popular idea of directing remains primarily about precision, control, and masculinity, then it should be no surprise that it often manifests as expressions of power over women — which often inflict real and lasting damage.

Shelley Duvall won Best Actress at Cannes in 1977 for her part in Robert Altman’s 3 Women, but her performance as Wendy Torrance in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, three years later, was criticized so harshly that it would ultimately overshadow everything else she accomplished in her career — even as the film has been used to bolster the claim that Kubrick is one of cinema’s greatest artists. Duvall, playing opposite Jack Nicholson as a woman tormented by her husband’s mounting, murderous rage, was nominated for worst performance at that year’s Razzies; Stephen King, who wrote the original novel, once said, “Shelley Duvall as Wendy is really one of the most misogynistic characters ever put on film. She’s basically just there to scream and be stupid and that’s not the woman that I wrote about.”

But as she explained in her own words, Duvall’s acting wasn’t a mistake, but rather a performance precisely engineered by Kubrick, who intentionally created a horrific environment for her:

"Going through day after day of excruciating work was almost unbearable. ... I had to cry 12 hours a day, all day long, the last nine months straight, five or six days a week. ... After all that work, hardly anyone even criticized my performance in it, even to mention it, it seemed like. The reviews were all about Kubrick, like I wasn't there.”

Nicholson has corroborated this description, calling Duvall’s task on set “the toughest job [of] any actor that I’ve seen.” There is even visual proof of that torment in the documentary Making “The Shining,” which was directed by Kubrick’s daughter Vivian and shows the director asking others on set not to show Duvall sympathy. Yet, despite this clear evidence of verbal and emotional abuse, Stanley Kubrick’s reputation as an “auteur” has remained mostly untouched.

In fact, the Duvall incident — and the way in which Kubrick controlled his set — has been wrapped into the mythic aura surrounding him and his film, casually inserted into lists like “25 Things You Might Not Know About The Shining,” alongside trivia like its record-breaking number of takes. Director Saul Metzstein once said of Kubrick that “his films are amazing, and there’s something in them which you couldn’t get unless you were being unbelievably particular and methodical. You need some sort of obsessiveness to make that stuff.” Not only is Kubrick considered one of the most influential directors of all time, but The Shining, specifically, was named the 46th best-directed film ever by the Directors Guild of America.

The implication of all this acclaim is that there was a “method” to Kubrick tormenting Duvall, and that even if it hurt her, the ends justified the means. From von Trier, who once said that watching Nicole Kidman wear a dog collar with a bell on it while shooting Dogville gave him “personal pleasure,” to Hitchcock, who sexually harassed Tippi Hedren while making a film about sexual violence, a man directing can rationalize almost any behavior toward women if what emerges as a final product is something beautiful in the eyes of other men.

And as Tom Shone points out, writing about auteur worship in 2012, even that beauty which men find onscreen is very often related to (as Mulvey said) sexual objectification and the need to control women’s bodies: "You could be forgiven for concluding that the most enduring definition of an auteur is a film-maker who populates his movies with women he wants to boff."

In their pursuit of beauty, men can walk away from these “incidents” unscathed, their reputations intact (if not enhanced), while the long-term impact on the women involved, personally and professionally, is largely ignored. Duvall has only appeared in a few films since The Shining and Hedren recently said in a tweet that her experience with Hitchcock (and others) eventually pushed her to leave the profession altogether.

This idea that directors should be all-powerful, uncompromising patriarchs, or as Kazan said in his speech at Wesleyan, that they must maintain “the firmness of an animal trainer,” is one of the foundational myths of modern filmmaking. And it is perpetuated by those who remain in power in the industry, who often idolize and model themselves after the dominant auteurs of the past. To continue to separate this myth from the reality of abuse, which women have reported on movie sets for decades, only tips the balance of power further toward those who are already calling all the shots.

Darren Aronofsky’s Mother!, a psychological horror film starring Jennifer Lawrence and Javier Bardem, has split audiences and critics alike this year. Some described it as a “sadistic spectacle,” while others, like Martin Scorsese, defended it as a work of true passion. In a New York Times piece profiling the director and his stars, a subtitle asks: “Is it the most confusing movie of 2017 or merely the most provocative?”

One thing that certainly emerges from Melena Ryzik’s profile is that Aronofsky, who has been called “Hollywood’s most ambitious director” and lists Kubrick’s films among his favorites, asked a great deal of Lawrence as an actress. At one point, she “hyperventilated, tore her diaphragm and had to be taken to the infirmary” while filming; Aronofsky not only kept the footage of Lawrence’s “breakdown” in the movie, but made her shoot the scene again “because we hadn’t quite gotten it yet.” Ryzik notes that the actress and the director are now dating (saying Aronofsky “bristled at the suggestion that the screen dynamic might be perceived as mirroring that of auteur and megastar in real life”), but her piece also describes what Bardem sees as the key to the chemistry between the duo on set: “She can telegraph pain on screen without needing hurt in real life; he can depict psychosis and remain steady himself.”

Though Aronofsky did not veer into clear harassment of his actor, this dichotomy echoes the underlying sentiment behind the incidents of abuse during the filming of Dancer in the Dark and The Shining, and how they were received by the press — the idea that, ultimately, creating these traumatic conditions was within the rights of the director as demigod, and worth it given the art that emerged. “It’s unlike any performance I’ve captured before,” Aronofsky says of the scene that so deeply rattled Lawrence. But it’s hard to imagine anyone but a white male “auteur” filming the same scene, being described that way by Bardem, or earning the same reaction to Mother! overall.

How often do women get to explore their “psychosis” on the big screen by inflicting pain on men? How often do legendary directors like Martin Scorsese write op-eds defending films in which people of other genders torture straight cis men? Moreover, could a black woman director express anger at her stars, like Kubrick and von Trier, and still retain her stature? Will a black woman ever have the freedom and studio support to make an allegorical film about her artistic anxiety, let alone release it in theaters nationwide?

At Pajiba, Kayleigh Donaldson recently put some of these discrepancies into stark contrast by comparing the careers of “noted bully” David O. Russell and Twilight director Catherine Hardwicke. Russell has been caught on camera savagely berating Lily Tomlin while shooting I Heart Huckabees, once physically attacked Christopher Nolan over a casting battle, and has been accused of inappropriately groping his niece (no charges were filed over the incident, although Russell admitted to touching her breasts). He not only continues to direct and win awards, but gets to make mediocre films like Joy without any seeming impact on his funding or reputation. Like Woody Allen, who has been accused of sexual abuse by his daughter (which he denies) and has made a number of commercial and critical flops, Russell’s standing as a “great director” appears to be untouchable.

Meanwhile, Donaldson relays this story about Hardwicke during the shooting of Twilight:

“Hardwicke admitted to going off-set for five minutes one day to have a quick cry. She got it out of her system and went back to work, where she has a reputation for her hard work, positivity and good cast and crew relations. Hardwicke did not get to make the sequel to the film she helped make a staggering success, with … sources saying the studio didn’t like her. … There was also talk that her brief moment of off-set crying was a sign of her being difficult. Later, Hardwicke pitched to direct a boxing drama called The Fighter. She was told a man had to direct it. David O. Russell got that job.”

Many women continue to work with Russell and some, like Oscar winner Lawrence, are active supporters of his work. But those choices do not negate the reality of other women. Amy Adams once recounted that Russell made her cry on the set of American Hustle, but that her costar’s reaction was much different than hers: “I was really just devastated on set. I mean, not every day, but most. Jennifer [Lawrence] doesn’t take any of it on. She’s Teflon. And I am not Teflon.” Excusing the abuse of men in filmmaking means that those who work with them on film sets, especially women, are expected to develop “thick skin.” It becomes proof of their commitment. And when they fail to reach this unreasonable standard of emotionlessness, they — rather than the directors who demand it — pay the price.

The hypermasculine standard of “great” filmmaking and the exclusive club of auteurship (much like the boys’ club of the studio boardroom) contribute to the fact that directing jobs in general are still mostly unavailable to women. And that fact isn’t unrelated to Hollywood remaining mired in the muck of abuse. If elite directing is defined by the dominance of men, and the denigration of all things feminine, it always risks lending itself to violent expressions of hypermasculinity. It not only echoes but reinforces the very hierarchies that allow rape culture to persist all around us.

It’s not that sexual harassment, the abuse of women, or a culture of dominance is unique to Hollywood. Last week, McKayla Maroney joined the long list of young gymnasts who have come forward with accusations of sexual abuse against a US Olympic team doctor Larry Nassar; photographer Terry Richardson has finally been banned from working with Condé Nast magazines, years after multiple women spoke out about his sexual abuse; new details continue to emerge about Bill O’Reilly’s endless string of settlements over sexual harassment while at Fox News; singer R. Kelly is accused of sexual coercion and mental abuse; our president has also been accused of sexual assault by multiple women. (Aside from Nassar, who has pled guilty to child pornography charges and is currently facing charges for criminal sexual conduct, all of these men either deny these accusations or have attempted to excuse their behavior.)

We know these crimes are about power and the structure of our larger society, where that power is given most frequently to the manliest of men, while other men — in fear of losing their own power — work to uphold the imbalance. Yet in the wake of Harvey Weinstein and so many other leading figures in so many industries being very publicly outed as abusers, it’s long overdue that we acknowledge that many of the “greatest” artists in our most influential visual artform continue to be celebrated for their own obsessive, often abusive exercises of power and control.

As long as the very craft of filmmaking is associated with this kind of hypermasculinity, the environment on film sets will continue to encourage the pain inflicted on women, and the “provocative” acts of men. But if the conversation around movies — namely who gets to make them, and how they do it — were to actually shift in the wake of this recent news, it could open a world of new possibilities.

There have always been women and people of other genders capable of directing film at the highest level, and that remains as true as ever. Artists like Dee Rees and Julie Dash continue to create, and so many others could be working far more often — if given the financial support and critical backing of the community. But as Selma director Ava DuVernay recently said about the Weinstein fallout, “I am not prepared to say there’s change, because it remains to be seen.”

Yet it is possible to imagine a day when film might begin to glorify a kind of respect, collaboration, and empathy behind the scenes that is truly centered on the leadership of women and femmes of color. Filmmaking, which requires so many different individuals to come together to create something beautiful, might even become a model for other workplaces. It hasn’t given us this radical vision very frequently, but popular cinema still has the power to show us all — especially men — another way to be. ●

Imran Siddiquee is a writer and filmmaker based in Philadelphia.