On 12 July 2013, there was an explosion outside the Kanzul Iman Masjid mosque in the quiet suburban town of Tipton, in the West Midlands.

In a twist of fate, Friday prayers had been delayed by an hour, which meant the bomb – wrapped in nails to maximise impact – did not kill or seriously injure the mosque's 300 worshippers.

The device was so powerful some nails were left embedded in tree trunks surrounding the mosque, police said.

Officers would later arrest and charge Pavlo Lapshyn, a 25-year-old Ukrainian student who, months earlier, had stabbed an 82-year-old Muslim man, Mohammed Saleem, to death. Lawyers described Lapshyn as a "white supremacist" who had plotted a series of attacks on mosques in order to "start a race war on the streets of Britain".

The Tipton mosque nail bomb was branded an act of terrorism and, in October 2013, Lapshyn was sentenced to 40 years in prison for his crimes.

Three years after the bomb went off, Mahtab Hussain, a 34-year-old British artist and photographer, released his book, "The Quiet Town of Tipton", commissioned by the arts organisation Multistory. The project captures Tipton's Muslim community in the years since the attack took place.

Hussain told BuzzFeed News he first visited the town a week before the bombing while researching possible projects. He says he had to take on the project in a different way, because the town was "such a quiet place".

"A week later, the attempted attack happened. And then [they found out] a Muslim man was killed by the same guy. All of this happened in a small town that nobody would [otherwise] have noticed."

Hussain has been making art about British Muslim communities for the past eight years, and his usual focus is the inner-city areas of Birmingham and London. But despite Tipton being a small, closed-off community, he said the Muslims there "were one of the most complex communities I've come across".

"It's relatively small compared to other areas," explained Hussain. "And Tipton itself is this incredibly quiet place, and people generally keep to themselves.

"So when the attempted attack happened – especially by someone who was outside of that community – it made Muslims there feel shocked and more vulnerable. This was all in the backdrop of 9/11 and 7/7, where young Muslims across the UK were not at ease with living in the UK.

“During my research it [was] evident that young Muslims are afraid. Some felt there was going to be a war against Muslims coming soon, and were afraid about what was going to happen to them.”

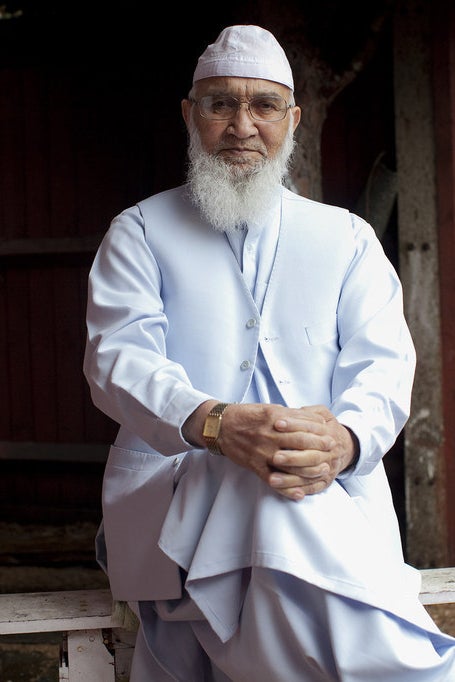

To complete the project, Hussain spent two years meeting Tipton's Muslim community, from imams of the town's few mosques to schoolchildren and well-known elderly residents.

"The community is strong, and closely knit," he said. "But there's also a sense of people questioning their identity. [The bomb] reinforced this fear that a war against Muslims will eventually be coming."

Though Hussain visited local mosques, he said the real stories about the town came from knocking on doors and meeting families. Many, he said, reminded him of his own family.

"They treated me like I was their son," he said. "They'd invite me in for tea and traditional Pakistani food. ... It's the type of hospitality they give to any guest. I'd meet their whole family, who would sometimes be living under one roof, or in close-knit quarters. It was a really lovely experience, and it showed a type of traditional biraderi [family kinship]."

Hussain was able to speak to community elders in Urdu, which he said they were more comfortable with. "They would tell me stories about how they arrived in the UK, how they would work in the factories, the construction plants, or making boiler parts," the photographer said. "They were keen to tell me how proud they were of coming to this country. They were so proud of being in the UK and being part of the community in Tipton."

One man who features in the project, Mohammed Thaj, told him about arriving in the UK from Pakistan at 16: "He was telling me about how he had never been to school in Britain, and that he had learnt how to speak English from his white co-workers in the factory." Hussain said Thaj's story was representative of many living in Tipton, where today 4.5% of the population are Pakistani.

The attack on Tipton had a profound effect on the town's older generation of Muslims – the people "who held the community together" in the wake of the attack, Hussain learned.

"The older generation had already gone through so much when they arrived in the UK, and they had to build their community with nothing," he said. "They're the reason why it is so strong and was able to hold together, even when they were targeted like that."

But Hussain found that the attack had done more to alienate the town's young Muslim population.

"Younger men and women in the community are increasingly leaving Tipton for work or for studying, but even for those that still live there, it's a more alienating place," he explained. "Many of the young people I spoke to said they had faced racism and verbal abuse because of their religion, while others are questioning whether they are even British.

"They feel they don't have a connection with their 'motherlands' ... but at the same time, racism, Islamophobia, and anti-Muslim sentiment ... has all made them feel they don't belong here either. It's a feeling they've had for a long time, but the attack was close to home. It had a huge psychological impact on them."

Hussain said he hopes his project will help challenge media stereotypes about Muslims and show how they have contributed to British society.

"The narrative that gets played out by the media sometimes is that Muslims hate the UK, or they hate British values. But that's false. I've always known that, coming from a British Muslim family and seeing these men and women give up so much of their lives and dreams for this country.

"They feel that the UK is their home, and they've worked hard to make it their home. It's a shame that this story isn't told more. So for me, as an artist, I wanted to celebrate what our parents and elders have done. And I hope that younger generations who see this are proud of them, and where they've come from too."