A Torres Strait Islander man who once won an Indigenous youth of the year award remains in immigration detention, despite a landmark decision from Australia’s highest court last week that Indigenous people cannot be detained or deported.

Billy Hohoi, 34, has been held in Sydney’s Villawood Immigration Detention Centre since April 2018, and says his Torres Strait Islander identity means he should not be deported to Papua New Guinea.

The High Court ruled last Tuesday that the special cultural, historical and spiritual connection Indigenous people — including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people — have with Australia’s land means that they cannot be treated as “aliens” under the Constitution. That means they cannot be deported or held in immigration detention, even if they are not Australian citizens.

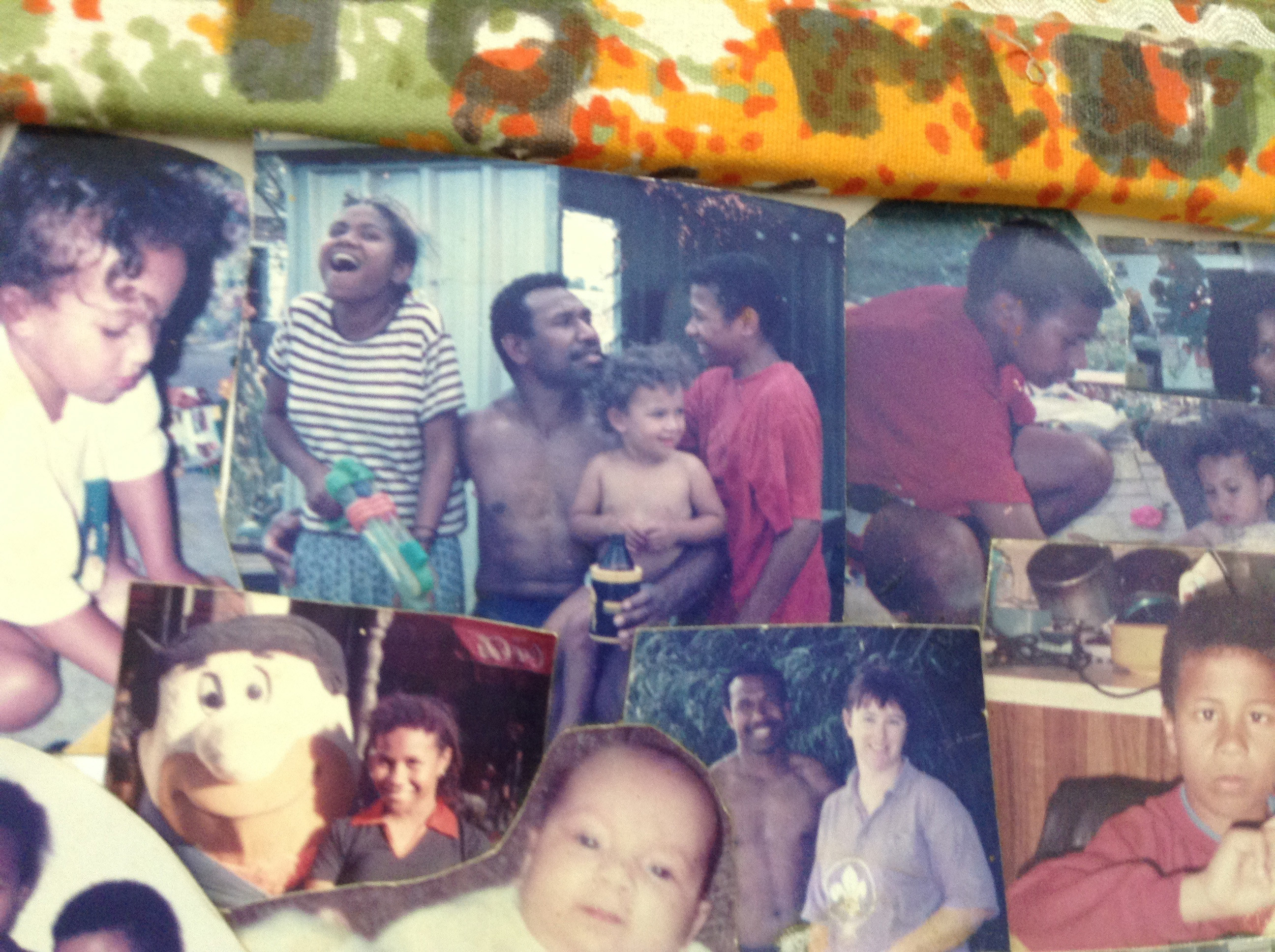

Alexandra Hohoi, Billy’s younger sister, told BuzzFeed News being Torres Strait Islander was a “huge, huge part” of the family’s identity.

As a teenager Billy played for the Lloyd McDermott Rugby Development Team, which fosters Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in rugby, including in a warm-up game for an Australia-All Blacks clash.

In 2002 Billy’s sporting achievements earned him the Australian Capital Territory’s Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Youth of the Year award.

But in 2018 he was taken to Villawood detention centre after serving a prison sentence, and was told by the Australian government he would be deported to Papua New Guinea, and would likely not be allowed to enter Australia again.

Billy’s lawyers at Victoria Legal Aid wrote to the Department of Home Affairs to seek his release on the day the High Court announced its decision. The department replied that his case was “being progressed”.

Throughout his detention Billy has argued that he is Indigenous and should be allowed to stay in Australia, where he has lived since he was seven.

Billy’s father, Tom Hohoi, was born on Mer (or Murray) Island in the Torres Strait, and he is part of the Mapa family of the Komet tribe. His work as a pastor took him just north of Mer Island to Papua New Guinea, where he met and married Billy’s mother, who died as a result of alcohol abuse when Billy was a young child.

Mer Island is best known as the home of Eddie Mabo, and the site of the first successful native title claim in Australian history. Tom Hohoi was one of the Mer Islanders approached by elders to sign a document indicating his support before Mabo brought his seminal case.

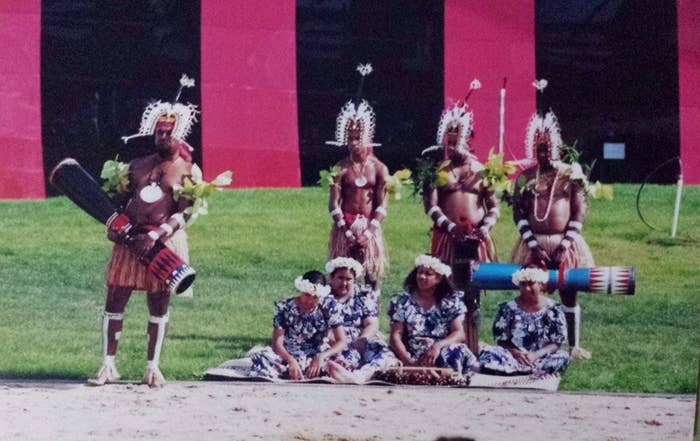

After Tom remarried, the family moved to Canberra, where Billy, Alexandra and their two sisters belonged to a small Mer Island community. Billy danced with the Gerib Sik Dance Torres Strait Islander dance group, including at the opening of the National Museum of Australia building in 2001.

Billy’s childhood was not easy. “I remember being a black family in white Canberra with no money,” Alexandra said. They grew up in a family with a “deep history of abuse”, which Billy experienced, she said. When he was 15 his step-mother and sister Alexandra moved to Cairns. Alexandra added that Billy was “extremely protective” of his three sisters.

From 18, he spent time in and out of prison for a range of offences, which were tried in Indigenous courts. In his early 20s, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and he has also been diagnosed with schizophrenia. His offences escalated in seriousness, and include aggravated robbery and assault occasioning actual bodily harm.

Alexandra and Billy’s step-mother Kristin remember an 18-month period in Billy’s early 20s when he stopped offending and worked in a regular job, but his progress was halted when he was jailed for an earlier offence.

Two weeks before he was set to be released in 2018, Billy received a letter indicating his visa would be automatically cancelled because of his offending. “We were looking forward to him coming home, and then he got shipped to Villawood,” Alexandra said.

Kristin told BuzzFeed News the letter felt like an ambush, and that Billy was “very, very scared”. He did not know he was not an Australian citizen. His father had lost his Australian citizenship when Papua New Guinea gained independence in 1975, and failed to reapply for it.

“He had no sense of the importance of doing that and it just wasn’t on his radar,” Alexandra said. “When you’re living in a community, you maybe don’t understand how [lacking citizenship] can affect your life.

“I think Indigenous people feel connected to the country and just not aware that any kind of legislation would ever change that, or confirm or deny it.”

Billy’s application for his visa to be reinstated was turned down eight months after he was taken to Villawood, despite the government’s decision-maker accepting that he identified as a proud Indigenous Australian. His lawyers challenged the decision in the High Court and the government eventually agreed it was unlawful.

Since mid-2019 Billy has been waiting for another decision. While in detention, his family believes he has not received the medical attention and medication required.

In the meantime, the family was watching the ongoing High Court case closely and nervously. “We knew that if it ruled the other way he’d have no chance of coming back,” Alexandra said.

Like Billy, the two men who brought the case had permanent Australian visas but not citizenship, and their visas were cancelled automatically due to criminal offending.

Their win made Alexandra “really hopeful”, she said. “But at the same time I’m wary of getting my hopes up because I just don’t know what’s going to happen.”

The four judges in the majority adopted a three-part test for Indigeneity. A person must have biological descent from an Indigenous people, identify as Indigenous, and be recognised as Indigenous by their community.

Billy “100%” meets that definition, Alexandra said. The government has not told his lawyers that it does not accept he is Indigenous. But the family has also not heard of any preparations to release him.

“The High Court found last week that Indigenous Australians can’t be deported. This has been our position for some time and we’re very pleased that the court agrees,” Victoria Legal Aid’s migration program manager Chelsea Clark told BuzzFeed News.

“Our client Billy has been locked up for years fighting deportation. He deserves to be set free.”

Victoria Legal Aid is also assisting Nyul Nyul and Nyikina man Jonathon Hirama, who remains in detention with a pending High Court case.

Clark said that although last week’s High Court decision related to Aboriginal Australians, that definition includes Torres Strait Islanders, who are the Indigenous people of the Torres Strait.

The government has reacted angrily to the decision, favouring the opinions of the three minority judges.

Home affairs minister Peter Dutton has suggested the government may try to legislate around the decision, which he described as “very bad”.

If Billy was removed to Papua New Guinea, “I honestly don’t think he’d make it”, Alexandra said. “We have no family in PNG, we have no connections there, we don’t know anyone.”

The family would not have the funds to visit him regularly, she said, and he would not have access to the treatment his serious mental health conditions require. He also has a child, nephew and niece in Canberra.

Alexandra says that if Billy was deported, the “saddest thing” would be the separation from his country.

“The thought that he couldn’t visit his own country would be so upsetting,” she said. “He always says, whenever we talk on the phone, the first thing he’s going to do when he gets out is come back up to the Torres Strait.

“Being held away from your home for a long time is hard, but particularly as an Indigenous person, when you have such a strong connection to it, it’s really hard.”

She believes Billy’s Indigenous background has led him to immigration detention.

“Billy just didn’t have a chance. It’s such a sad, classic story,” Alexandra said. “A young black boy being caught up in a bad system, and intergenerational cycles of abuse.

“To have the same government who crippled us with these cycles, then turn around and kick our brother out just feels wrong.”